- Home

- Our Stories

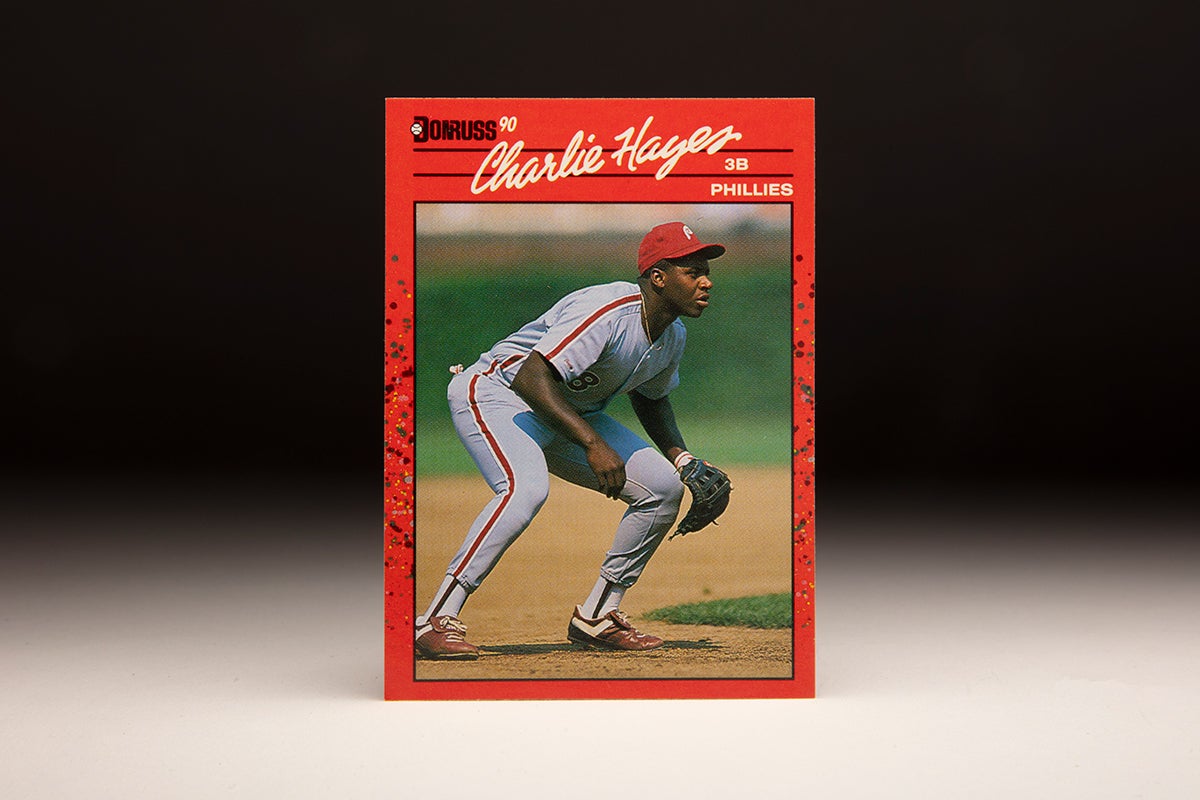

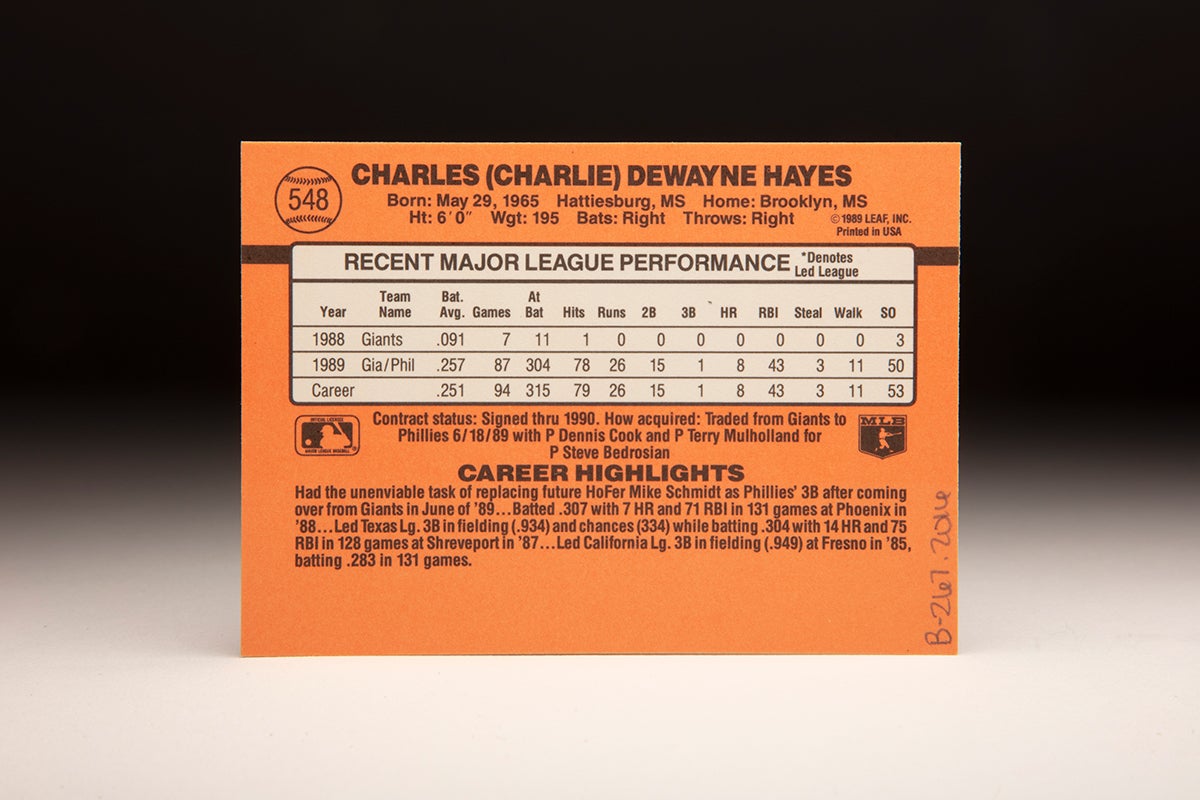

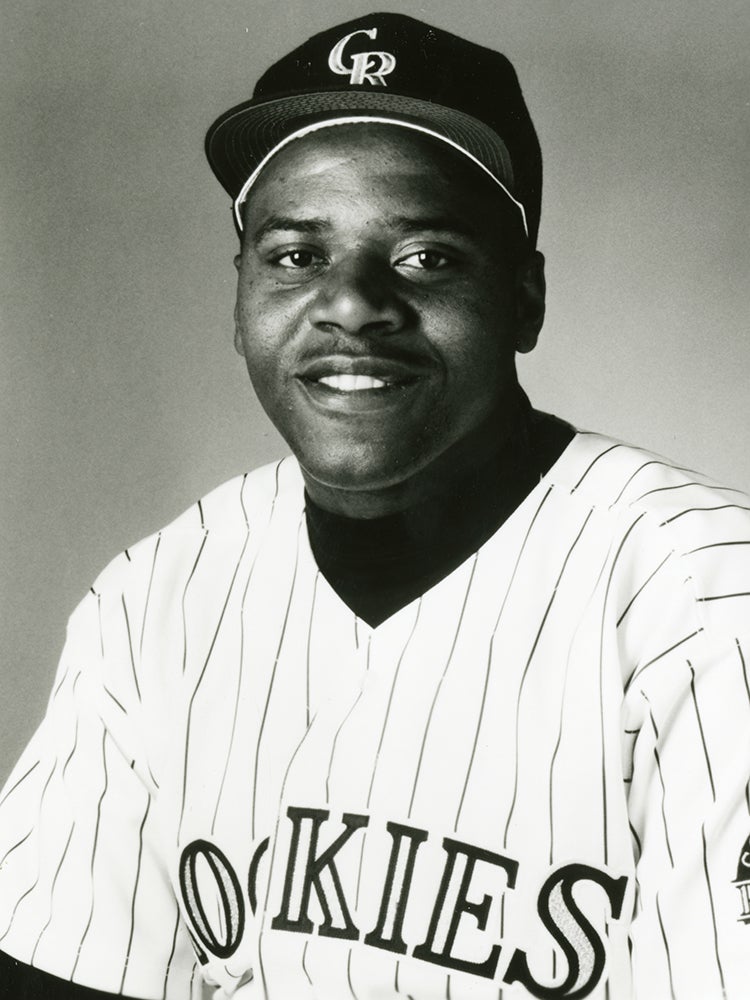

- #CardCorner: 1990 Donruss Charlie Hayes

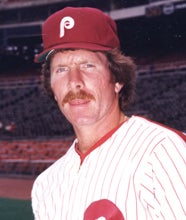

#CardCorner: 1990 Donruss Charlie Hayes

For many Yankees fans, the sight of Charlie Hayes catching a popup to end the 1996 World Series marked the beginning of what became a dynasty in New York.

For Hayes, it was one of the highlights of a career that saw him become one of the best third basemen in baseball.

Charles Dewayne Hayes was born May 29, 1965, in Hattiesburg, Miss. His first love was basketball, but soon Hayes showed exceptional skills on the diamond, especially as a pitcher. In 1977, he led Hub City of Hattiesburg to the Little League World Series in Williamsport, Pa., shutting out Belmont Heights of Tampa, Fla., 1-0, on one hit in the South Region title game.

Belmont Heights’ cleanup hitter was nicknamed “Dr. D”. He would soon be known to the world as Dwight Gooden.

“I remember the way (Belmont Heights) walked around the camp in their slacks,” Hayes told the Hattiesburg American in 1987. “There we were walking around in jeans and T-shirts. And they kept telling us: ‘There’s no way you’re going to beat Dr. D; Dr. D’s never been beaten.’”

But Hayes and Hattiesburg prevailed to advance to Williamsport. Starting the first game of the LLWS on the mound, Hayes limited El Cajon, Calif., to three runs but lost a hard-luck 3-1 decision. El Cajon went on to win the United States title before losing to Taiwan in the finals.

Hayes, meanwhile, allowed just four hits while using his big curveball to strike out 10 batters in the consolation bracket final to defeat a team from Youngstown, Ohio, 9-2.

“Charlie Hayes was the jewel, the stick that stirred the drink,” Hattiesburg coach Ken Fairley told the American in 1987 during a 10th anniversary celebration for the team. “The pitching performance he had against Belmont Heights was masterful.”

Hayes would put his arm to use at third base in the big leagues. But the experience of playing at the world’s top level as a grade schooler prepped him for his journey to the majors.

“I had never been anywhere and it made me realize I could play this game,” Hayes told the American. “If that’s what I wanted out of life, that’s what I could do.”

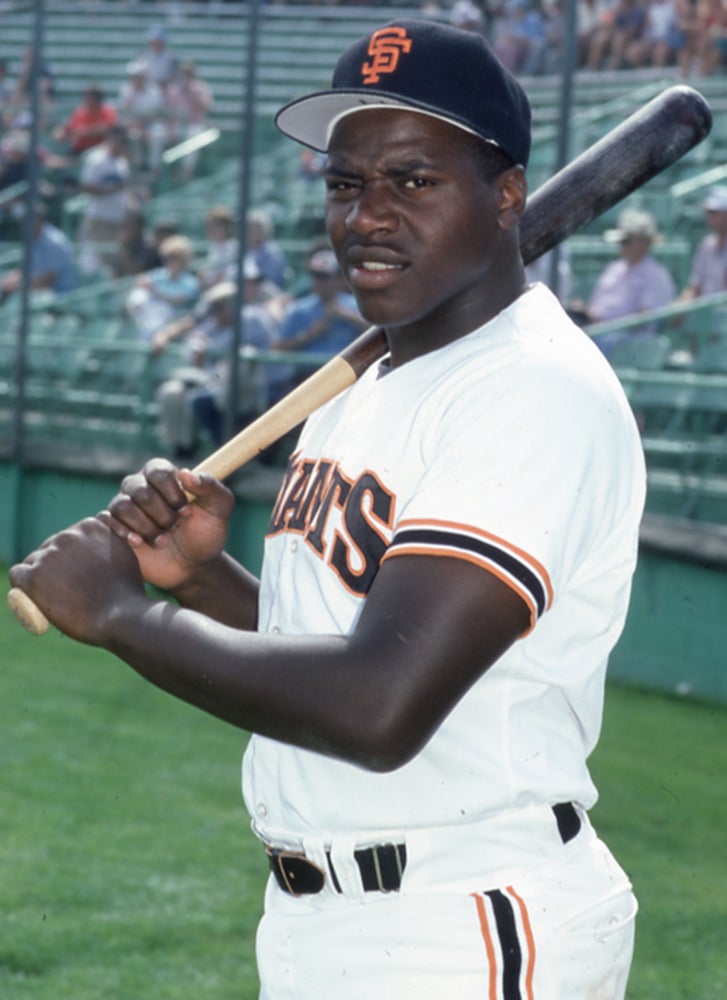

Hayes emerged as a star in basketball and baseball at Forrest County Agricultural High School in Brooklyn, Miss., located just south of Hattiesburg. Following his graduation in 1983, the Giants took him in the fourth round of the MLB Draft.

Sent to Great Falls of the Pioneer League, Hayes batted .261 in 34 games while making eight errors in 50 chances at third base. Though he was 8-3 on the mound as a high school senior, most scouts projected Hayes as a third baseman before the draft.

In 1984, Hayes played for Class A Clinton of the Midwest League and hit .245 in 116 games – and did not play any position but third base in the field. Then in 1985, Hayes hit .283 for Class A Fresno of the California League. He was named to the league’s All-Star team and developed a reputation as one of the best fielding third basemen in the minors.

Making the jump to Double-A in 1986, Hayes struggled at the plate, hitting .247 with a .343 slugging percentage for Shreveport. The Giants sent him back to Double-A in 1987, and this time Hayes hit .304 while showcasing power for the first time by hitting 33 doubles and 14 homers.

In 1988, Hayes batted .307 for Triple-A Phoenix while playing almost two-thirds of his games in the outfield. And when the Giants brought Hayes to the major leagues in September, he played both the outfield and third base during his seven contests. The issue at hand was Matt Williams, one of the game’s top prospects who debuted with the Giants in 1987 and looked to be the third baseman of the future.

Williams was the Opening Day third baseman for the Giants in 1989 while Hayes returned to Phoenix. He was recalled in May but appeared in only three games before returning to Triple-A. Then on June 18, Hayes got the break he needed when the Giants packaged him along with pitchers Dennis Cook and Terry Mulholland in a deal that brought Steve Bedrosian and a player to be named later (who became Rick Parker) to San Francisco.

That same day, the Phillies traded Juan Samuel to the Mets in exchange for Lenny Dykstra and Roger McDowell. It was the beginning of a rebuild that started when future Hall of Fame third baseman Mike Schmidt retired suddenly in May and would pay off with a National League pennant in 1993, by which time Hayes was starring for the Rockies. But for the time being, the Phillies had Schmidt’s successor at third base.

After being initially sent to Triple-A Scranton/Wilkes Barre, Hayes was recalled after about a week and stepped into the starting lineup at the hot corner. He remained there the rest of the year, batting .258 with eight homers and 43 RBI in 84 games. Though his 22 errors ranked third among all NL third basemen, Hayes flashed the potential that made him a top prospect. He eventually finished fifth in the NL Rookie of the Year balloting.

However, Hayes often clashed with manager Nick Leyva, who was critical of Hayes’ fielding and conditioning.

“I hope Charlie Hayes learned something from the things I said,” Leyva told the Camden (N.J.) Courier-Post on the final day of the 1989 season. “I want him to be the best player he can be. He has two kids and a wife and I think he can make a lot of money someday. I just don’t want him to screw it up.”

But Leyva took a different approach with Hayes in the spring of 1990, building up his young third baseman even as prospect Dave Hollins was turning heads in camp.

“I don’t think there is any (competition),” Leyva told the Courier-Post. “It’s Charlie Hayes’ job.”

Hayes rewarded Leyva with a strong sophomore season, batting .258 with 20 doubles, 10 homers and 57 RBI in 152 games after dropping 20 pounds in the offseason. Defensively, Hayes led all NL third basemen with 324 assists while finishing third in fielding percentage with a .957 mark.

But in 1991, a protracted slump – one that saw him go 5-for-62 at one point – cost Hayes playing time. New manager Jim Fregosi, who took over for Leyva early in the season, began to platoon Hayes with Wally Backman and then turned to Hollins in July.

“I’m just hoping I can get in there and work my problems out,” Hayes told the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Hayes bounced back during the second half of the season, finishing with similar home run (12) and RBI (53) totals to his 1990 numbers but batted only .230.

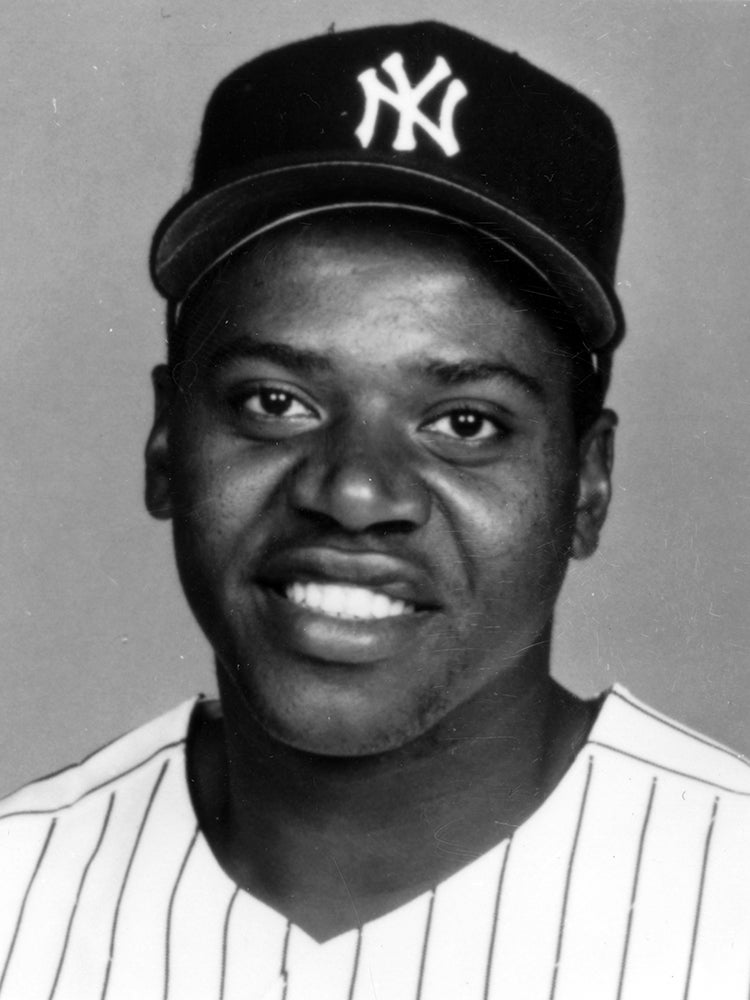

With change in the air, the Phillies traded Hayes to the Yankees on Feb. 19, 1992, in a trade that began on Jan. 8 when New York sent pitcher Darrin Chapin to Philadelphia for a player to be named later.

“I hate the way it happened,” Hayes told the Philadelphia Daily News toward the end of Spring Training of 1992 when he was competing with Hensley Meulens for the Yankees third base job. “I wasn’t in their plans for this year. They liked Hollins better, and that’s fine. It ain’t the first time. The Giants liked Matt Williams better.

“But I think a lot of people got the wrong impression of Charlie Hayes. A lot of people thought I had a bad attitude and that I was hard to get along with. That’s frustrating.”

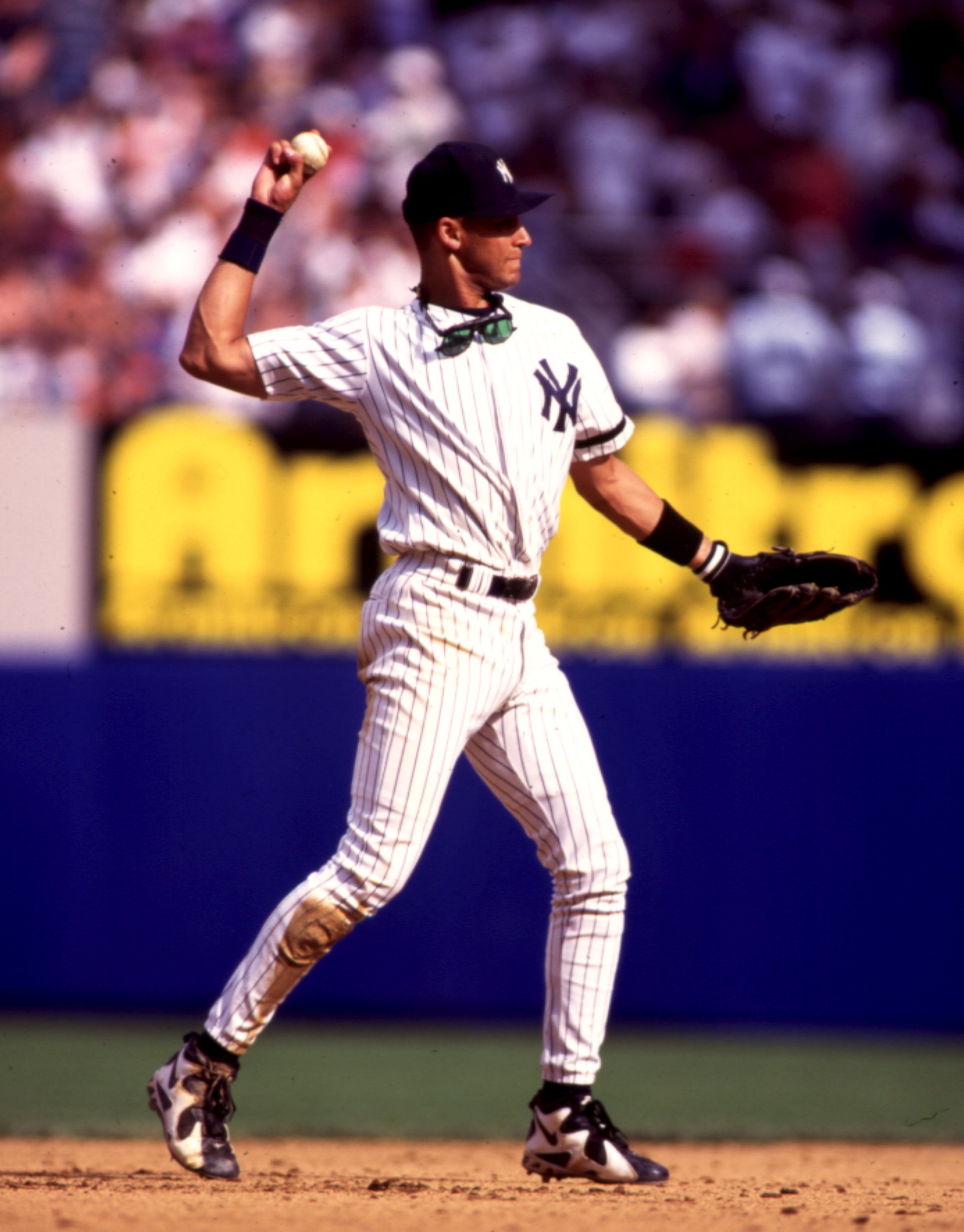

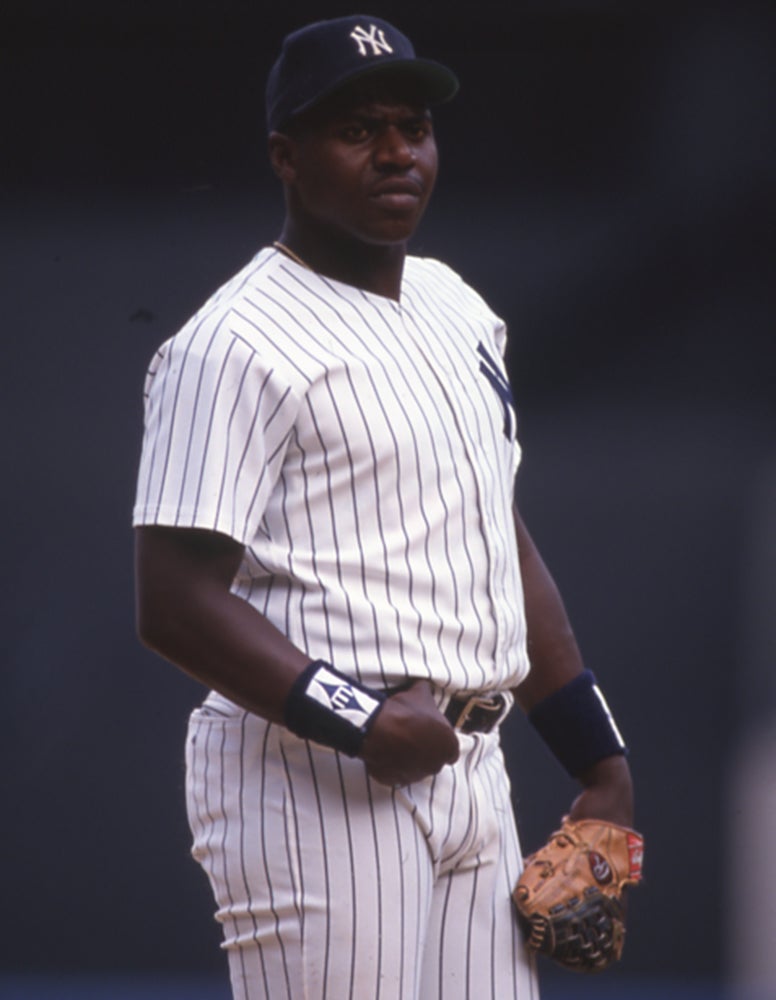

Hayes won the job as the Yankees’ starting third baseman and got off to a fast start, batting .325 with nine RBI through April. He solidified a position that had been a headache for the Yankees, who used 10 third basemen in 1990-91 – players whose combined production totaled 18 home runs and 88 RBI. By himself, Hayes had 18 homers and 66 RBI in 1992 while batting .257 and committing only 13 errors while leading the league by turning 29 double plays.

But with the Expansion Draft to stock the Colorado Rockies and Florida Marlins set for that fall, the Yankees had tough choices to make. They decided to leave Hayes unprotected, and the Rockies grabbed him with the third overall pick.

“We gambled a little bit. We gambled on young players,” Yankees general manager Gene Michael told Gannett News Service. “We thought maybe we could get (Hayes) past the first round.

“We like Charlie Hayes. He did a fine job for us. We know that. He’s one of the top (defensive third basemen), if not the best.”

Less than a month after losing Hayes, the Yankees signed future Hall of Famer Wade Boggs to play third base.

Hayes, meanwhile, stepped into a stacked Rockies lineup that featured Andrés Galarraga and Dante Bichette. Hayes led the NL with 45 doubles and paced the Rockies with 175 hits, 25 home runs and 98 RBI (tying Galarraga for the team lead) while batting .305.

Hayes played under a $1.2 million contract in 1993 – the top salary on the Rockies – after he and the team came to an agreement prior to an arbitration hearing. Hayes got a raise to $3.075 million for 1994 and hit .288 with 10 homers and 50 RBI in that strike-shortened season. He played in 113 of the Rockies’ 117 games that year despite being hit in the cheek by a pitch from San Francisco’s Salomón Torres on June 25 – an incident that sparked a mele and left Hayes with a broken left cheekbone.

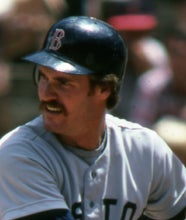

But despite his two excellent seasons, Hayes was not offered a contract by the Rockies for 1995. On April 6, 1995, the Phillies offered Hayes a one-year deal worth $1 million plus $500,000 in incentives – the same deal they had offered Terry Pendleton and Mariano Duncan. Hayes accepted the offer that Pendleton and Duncan turned down and returned to Philadelphia.

“Charlie left here with some things people didn’t like, me included,” Phillies general manager Lee Thomas told the News Journal of Wilmington, Del. “I think Charlie has changed a lot since then. It was a tough time. Charlie was following Mike Schmidt. That wasn’t easy.”

Hayes outperformed his contract in 1995, hitting .276 with 30 doubles, 11 homers and 85 RBI in 141 games while finishing second among NL third basemen with a .963 fielding percentage. He also finished 16th in the NL Most Valuable Player Award balloting, the first time in his career he earned such notice.

But with top prospect Scott Rolen nearly ready to take over at third base, the Phillies let Hayes become a free agent once again following the season. Hayes signed a four-year deal with the Pirates worth a reported $7.15 million and immediately impressed his new Pirates teammates by mentoring young players in the clubhouse.

“He’s a terrific fellow,” Pirates shortstop Jay Bell told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “He enjoys people. He’s the kind of person who likes to communicate.”

Hayes was hitting .248 with 10 homers and 62 RBI in 128 games with Pittsburgh but the Pirates were en route to an 89-loss season. On Aug. 30, Pittsburgh traded Hayes to the Yankees in exchange for a minor leaguer, Chris Corn, who would never play in the majors.

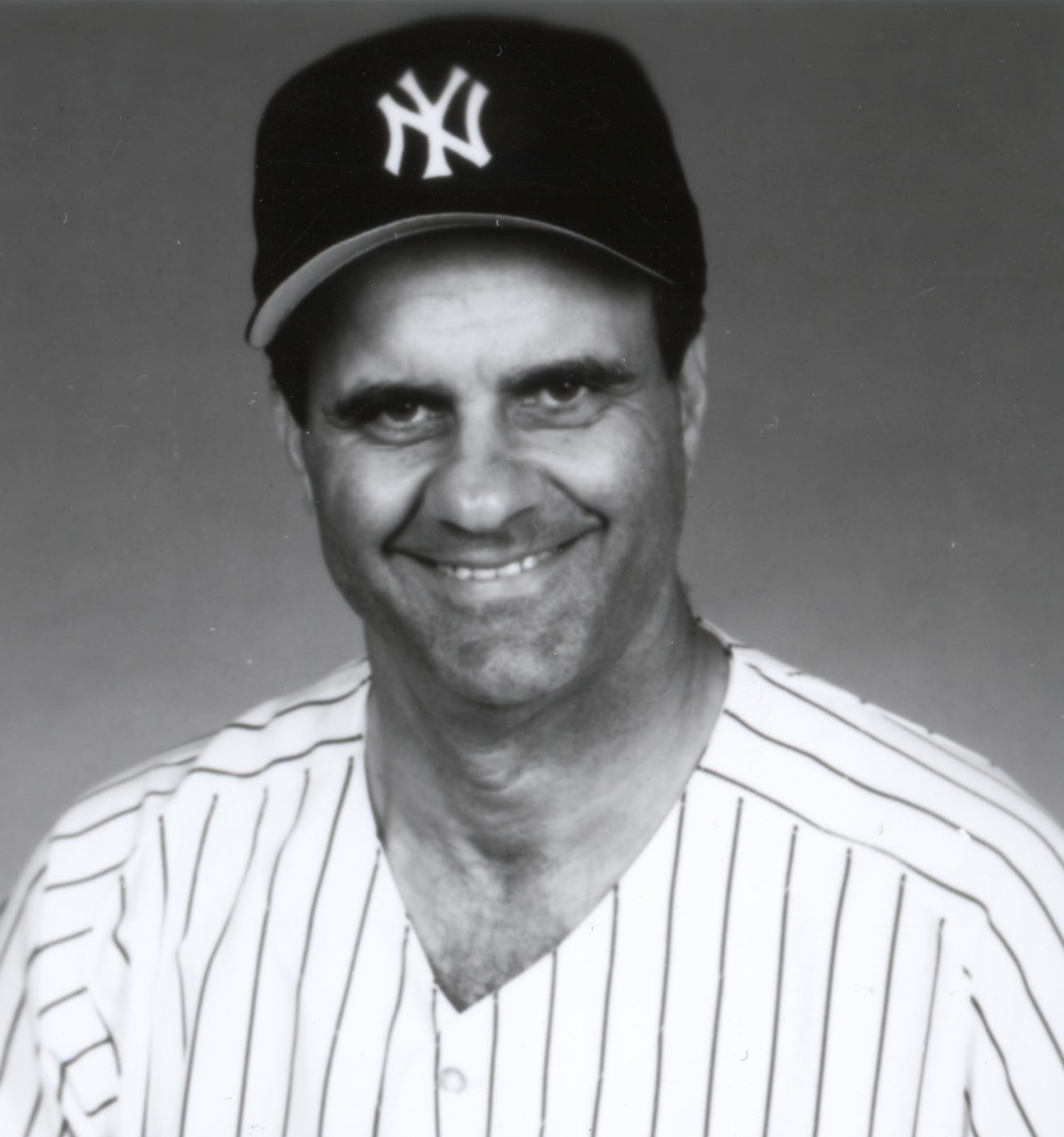

Hayes was expected to platoon at third base with Boggs, who was in his age-38 season.

“He’s tired,” Yankees manager Joe Torre told Gannett News Service about Boggs. “He’s been playing a lot. When I rest him, we’ve had Luis Sojo at third base, and we need a little more offense.”

But while Boggs was not pleased at the prospect of lost playing time, Hayes was thrilled to return to New York and enter a pennant race.

“(Pirates manager Jim) Leyland called me in and told me a trade was in the works with New York,” Hayes told the Hattiesburg American. “I thought to myself: ‘It must be the Mets’ because that’s kind of how the year had been going. When he told me it was the Yankees, you don’t know the feeling I had.”

Hayes batted .284 with two homers and 13 RBI in 20 games for the Yankees as New York won the American League East title. Appearing in the postseason for the first time, Hayes was a combined 2-for-12 in the ALDS and ALCS as the Yankees advanced to the World Series. But with lefties Tom Glavine and Denny Neagle in the Atlanta rotation, the right-handed hitting Hayes started in Games 3 and 4 of the World Series as Hayes became the first native of Hattiesburg to play in Fall Classic.

His wife, Glenda, was pregnant at the time with their third child, Ke’Bryan – who would go on to be a Gold Glove Award winner at third base for the Pirates more than 20 years later. Another son, Tyree Hayes, was an eighth-round draft pick of the Devil Rays in 2006 and pitched in the minor leagues for seven seasons.

In Game 4 of the World Series, Hayes played a key role in a rally that saw the Yankees recover from an early 6-0 deficit. Batting against Neagle in the top of the sixth, Hayes singled to drive in Cecil Fielder and cut Atlanta’s lead to 6-3. Then in the eighth, Hayes singled off Mark Wohlers to lead off the frame and later scored on Jim Leyritz’s three-run homer that tied the game.

With the score still tied at 6 in the top of the 10th, Torre called on Boggs to pinch-hit for Andy Fox with the bases loaded and two outs. Boggs worked a full count walk off Steve Avery to drive in the go-ahead run, and Hayes followed with a popup that was ruled an error after it fell to the ground on the right side, driving in Derek Jeter to make the score 8-6.

Graeme Lloyd and John Wetteland combined to blank the Braves in the bottom of the inning, giving New York a victory that tied the series at two games apiece. Hayes started Game 5 and scored the game’s only run after reaching second base to lead off the fourth inning on an error charged to Braves center fielder Marquis Grissom and scoring on a Cecil Fielder double.

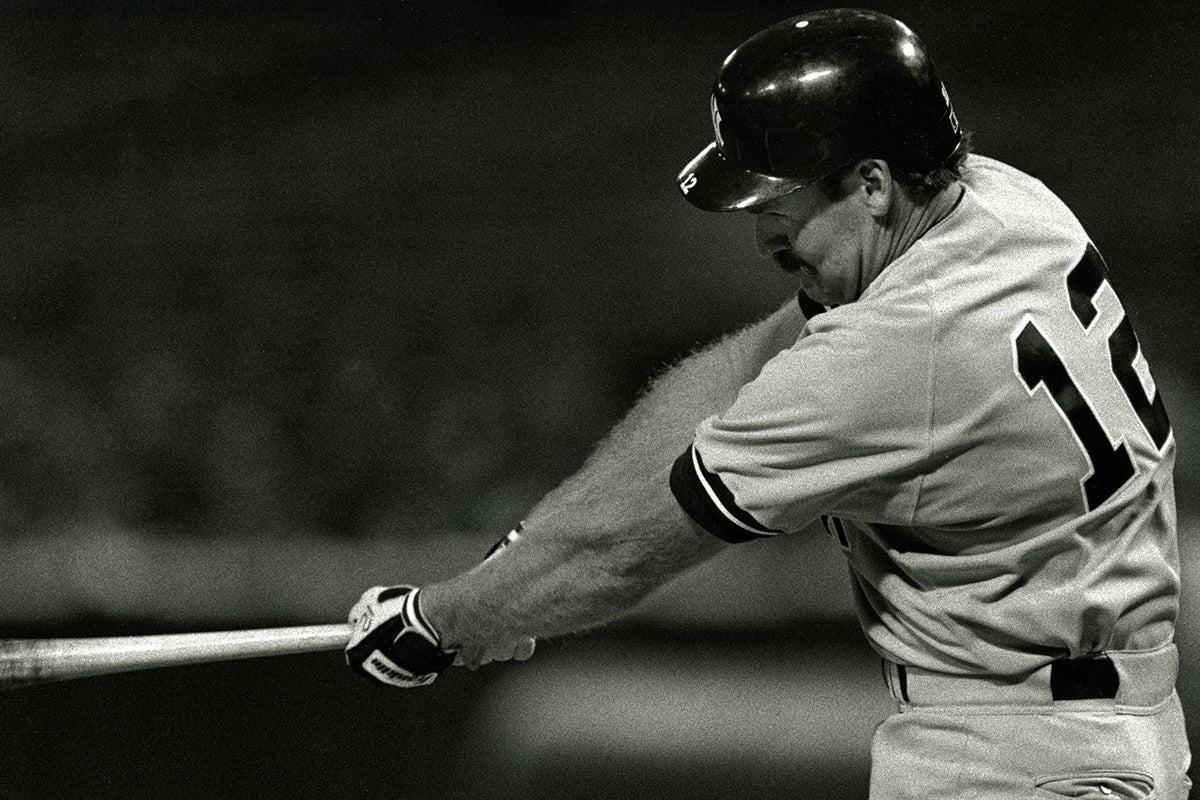

Then in Game 6, Hayes replaced Boggs at third base in the seventh inning with the Yankees leading 3-1. With the same score in the ninth inning, Yankees closer John Wetteland retired Andruw Jones before allowing singles to Ryan Klesko and Terry Pendleton. After Luis Polonia fanned, Grissom singled to right to score Klesko and move pinch-runner Rafael Belliard to second.

With Mark Lemke at the plate, Hayes seemed to have a chance to end the game when a 3-and-2 popup drifted toward Atlanta’s dugout. But Hayes got slightly impeded by a Braves batboy and the ball fell into the dugout, along with Hayes.

On the next pitch, Lemke hit a similar popup – but this one stayed in play down the third base line near the stands. Hayes backed under it, pounded his glove once and squeezed the ball to give the Yankees their first World Series title since 1978.

“Right before the last ball was hit, I was trying to decide if I should go out and talk to (Wetteland) and (coach Don) Zimmer said ‘Don’t worry about it, the next pitch is for Frank,’” Torre told Gannett News Service, referring to his brother, Frank Torre, who had undergone a heart transplant just days earlier. “The next pitch… Charlie Hayes catches it. This is a dream.”

Hayes and the Yankees returned to the postseason in 1997 after Hayes hit .258 with 11 homers and 53 RBI in 100 games as he once again shared time with Boggs. Hayes hit .333 (5-for-15) in the ALDS but New York lost to Cleveland in five games.

On Nov. 11, 1997, the Yankees sent Hayes back to his original team – the Giants – in exchange for Alberto Castillo and Chris Singleton.

“Charlie’s a clutch man, a run producer. And he’s been on winning teams,” Giants manager Dusty Baker told the AP after the trade, noting that the Giants would use Hayes in a platoon with Bill Mueller. “We’re going to try to utilize Charlie as much as we did Mark Lewis, to keep (Mueller) strong.”

Hayes appeared in 111 games in 1998, hitting .286 with 12 homers and 62 RBI. But he slumped to .205 over 95 games in 1999. With his contract expiring, Hayes became a free agent and signed with the Mets. But New York released him on March 20, and two days later Hayes signed with the Brewers. He quickly found a role at first base, moving into the cleanup spot in mid-April.

“He’s been pretty successful so far,” Brewers manager Davey Lopes told the Wisconsin State Journal. “He’s a proven veteran and he’s been very productive.”

Hayes appeared in 121 games that year, batting .251 with nine homers and 46 RBI. But the Brewers did not bring Hayes back in 2001. He signed with the Astros on Jan. 2 and won a job as a bench player – but Hayes was forced to leave the team for two weeks in late April/early May when his mother, Lutherea, passed away.

Hayes was hitting .200 with no home runs and four RBI through 31 games when the Astros released him on July 9. He would not play in the major leagues again.

Hayes spent the next few years coaching youth baseball before returning to the Phillies as a minor league instructor. He finished his career with a .262 batting average, 1,379 hits, 144 home runs and 740 RBI in 1,547 games.

But it was a game that didn’t count in those statistics – Game 6 of the 1996 World Series – where Hayes made himself into a player that Yankees fans will never forget.

“Some people might think I am lucky because of the trade,” Hayes told the Hattiesburg American after he was acquired by the soon-to-be world champion Yankees in 1996. “But I don’t consider it luck. I’ve worked my tail off for 13 years. I deserve to be here.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum