- Home

- Our Stories

- April Fools: Baseball's Legendary Princes

April Fools: Baseball's Legendary Princes

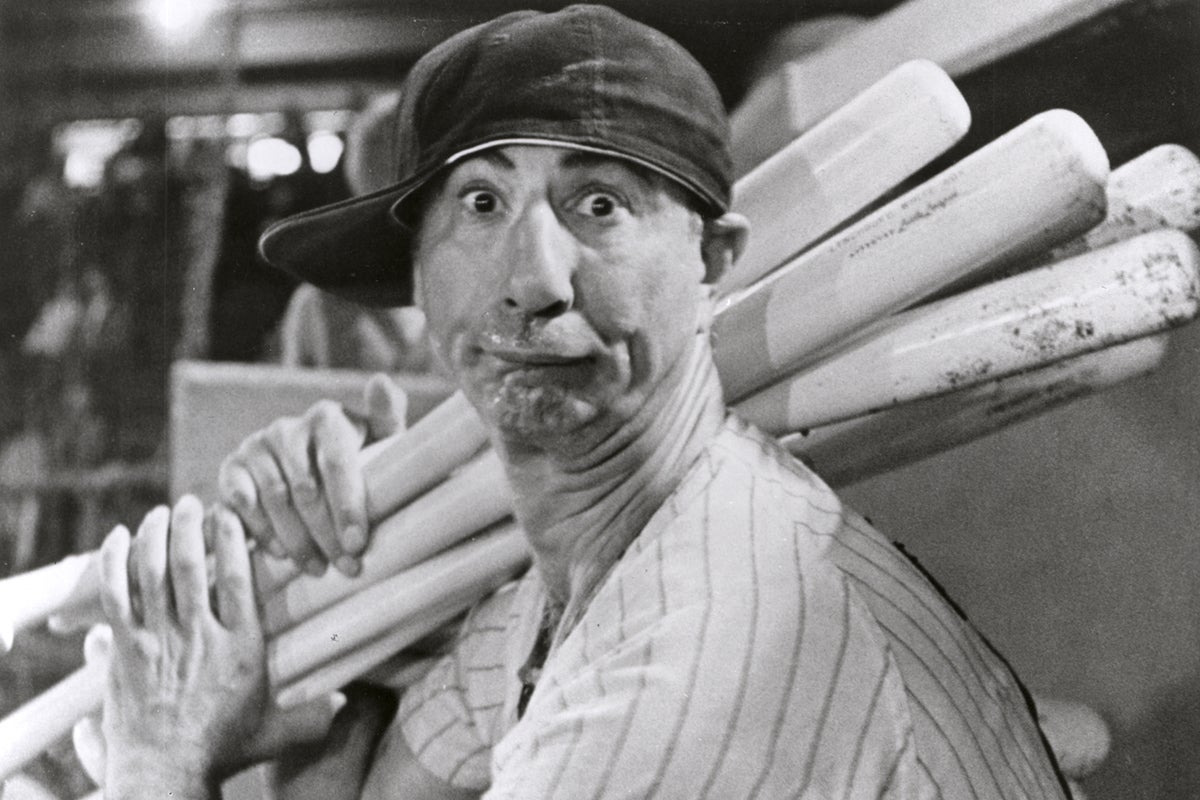

The Clown Prince of Baseball.

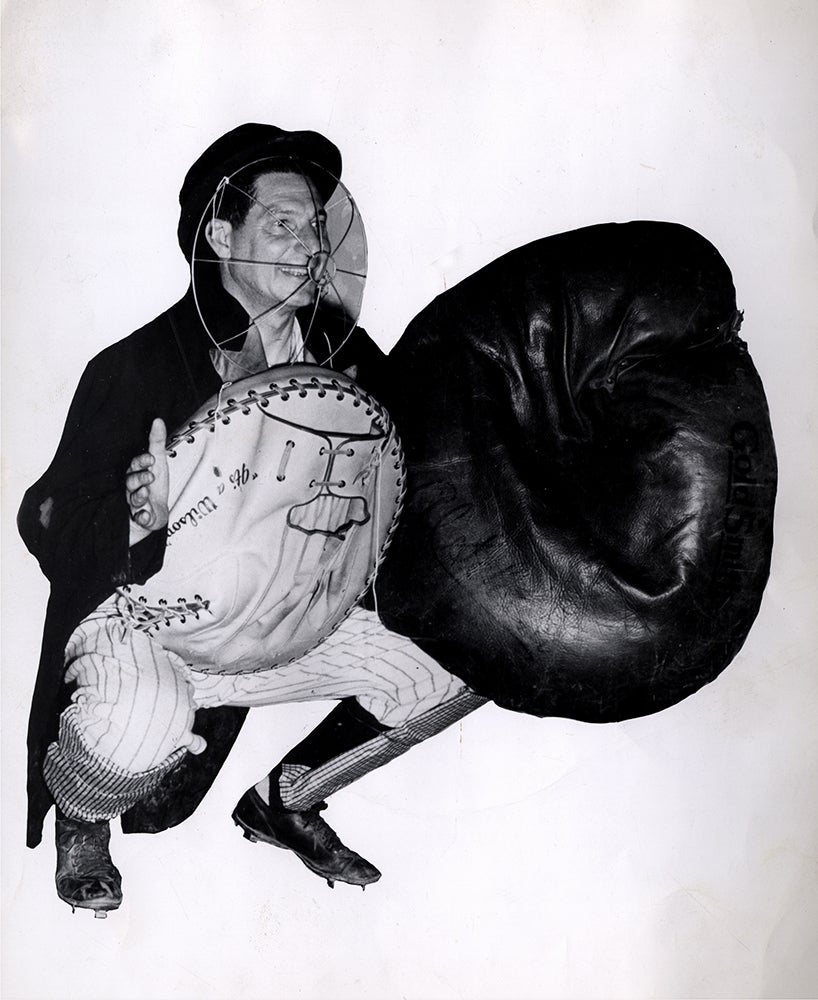

The title alone conjures up images of goofy, Harlem Globetrotter-type images on the baseball field. From Al Schacht and his oversized glove, to the famous water geyser act of Max Patkin, the Clown Prince title has been away for people to enjoy the game on a whole new level.

But the legacy of the men who held the title is anything but frivolous. For several generations, the Clown Princes have helped keep minor league baseball alive.

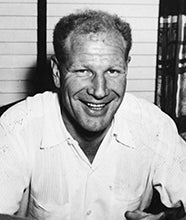

Al Schacht had a very limited major league career. He pitched only three seasons, all with the Washington Senators, compiling a 14-10 record with an ERA of 4.48, numbers to inspire legendary status within the game. However Schacht had another talent: the ability to make people laugh.

Schacht and teammate Nick Altrock, also a struggling player, were not incredibly fond each other. However they had two things in common. First was a love for the game of baseball. Second was an incredible ability to entertain. Knowing their playing careers were limited, Schacht and Altrock teamed up to become the first Clown Princes of Baseball.

As coaches for the Washington Senators, Schacht and Altrock did their best to keep the crowd entertained off the field. Schacht was famous for his 25 pound glove which was big enough to eat a meal out of, which he often did. In addition, Schacht once took the meaning of “home plate” a little too literally and ate his pre-game meal off the dish.

Schacht continued his act through World War II, despite a trade which ended his partnership with Altrock. Not only did Schacht entertain at the ballpark, during World War II, the World War I veteran entertained the troops in North Africa and Pacific, bringing baseball as a little slice of home for the men stationed overseas.

After World War II, Schacht’s path would eventually cross with his successor to the title of Crown Prince of Baseball, thanks to none other than the legendary baseball owner Bill Veeck.

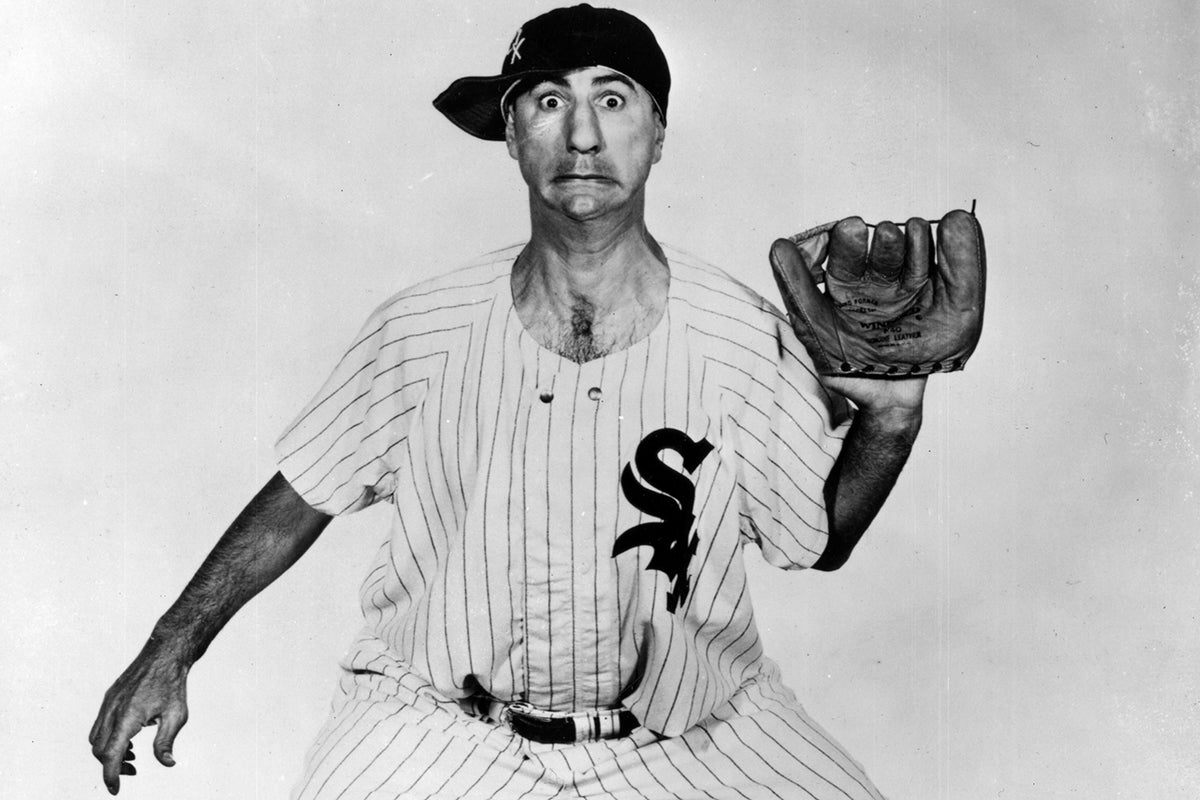

“Someone had started at the top and finished in the middle. For one thing, they forgot to put the bones in. He looked as if they found him on a broomstick in a cornfield,” Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray once described Schacht’s heir, Max Patkin.

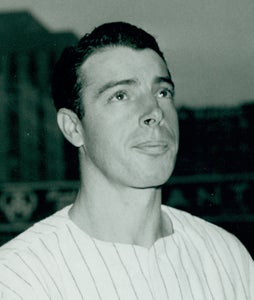

Patkin’s reputation as a baseball funny man began in World War II when he was on the mound for an Army-Navy baseball game. After giving up a home run to Yankee great Joe DiMaggio, Patkin followed him around the bases, imitating him. When DiMaggio’s teammates wanted to shake Patkin’s hand instead of the Yankee Clipper, Patkin realized comedy could be the way for him to stay in the game he loved so dearly.

Patkin’s first major league appearance came in 1946 with the Cleveland Indians. Manager Lou Boudreau felt Patkin would annoy their opponents and convinced owner Bill Veeck to sign him, letting him coach first base for the first two innings of each game. At the Indians’ home opener that year, they were honoring former major leaguers Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker, leading to a full house of 80,000 people at Cleveland Municipal Stadium. In addition, Al Schacht was performing before the game.

As Schacht was performing, Ruth made a comment about his disdain for Schacht and decided to go out and take a few swings. Despite the fact he was ill and would pass away just two years later, the Babe took about a dozen swings, mostly weak ground balls through the infield. Schacht left the field in disgust at being upstaged. Patkin wrote in his 1994 autobiography that it was the loudest crowd he had ever heard.

The next clown prince was concerned that people would feel the same way about him as Ruth did about Schacht. The concern especially rang true when the sportswriters decried him as a sideshow and referred to visiting Indians teams as Bill Veeck’s Circus coming to town. In his autobiography, The Clown Prince of Baseball, Patkin said Veeck comforted him.

“He taught me that as long as they’re writing about you, the public knows about you,” the Hall of Fame owner told him.

Patkin would continue with the Indians through 1947, however things were changing in Cleveland. Boudreau felt the Tribe could contend but was nervous about Patkin being a distraction. Patkin was let go, but had made a friend for life in owner Bill Veeck. Veeck helped Patkin find jobs throughout the minors and his traveling act began.

Patkin would go on to have over 4,000 consecutive appearances before finally missing one due to an injured ankle in 1993 in New Britain, Conn. He retired that year and wrote his autobiography the following one. He passed away in 1999 at the age of 79, feeling he would never have an heir as the Clown Prince of Baseball.

“It’s a small kingdom. I’m the only one out there. And when I go, nobody will move into that slot. The travel is too punishing, the pay too skimpy, the life too lonely,” Patkin wrote. While he certainly spent most of his career touring the minor leagues, Patkin’s most famous exploit was his role in the baseball comedy Bull Durham.

“Appearing in Bull Durham put new life into my career. Which is funny because I was supposed to die in the original script,” Patkin explained. The movie opens with Patkin performing at a Durham Bulls game and really gets moving when he introduces Annie Savoy, played by Susan Sarandon, to Kevin Costner’s Crash Davis at a bar following the game.

Originally the scene called for Savoy to ask Patkin why he continues to tour, year after year. Patkin was to explain his love for the game and express his last wishes – to have his ashes spread out at home plate and placed in the rosin bag so he can always be part of the game. The script called for Patkin to drive past the bus clowning around and waving to the team on the bus. Later, word would come he had been hit by a train. The ashes would be sent to Annie and Tim Robbins’ “Nuke” LaLoosh would be shown with the rosin bag in his hand.

Perhaps for the better, the sad scene was cut out of the movie and Patkin became the endearing character that allowed Annie and Crash to meet. At the time of this autobiography, Patkin had still not viewed the movie. “I just don’t like to look at myself,” he quipped.

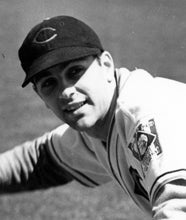

While the career of the Clown Prince was winding to a close, Bull Durham allowed one last hurrah for the title bestowed upon Schacht and Patkin, among a few others, including Patkin’s partner in Cleveland, Jackie Price. Price spent years as a shortstop in the minor leagues and had a short stint in the majors playing in just seven games. Once he realized his dream of being a major league star may never happen, he began developing tricks that could keep him in the game of baseball.

One of Price’s best included taking batting practice while hanging upside down for 15 minutes or more. Price could catch balls behind his back and between his legs. He could pitch two balls at once, one a curveball and the other a fastball. He even carried 20 snakes with him on road trips to use in his act. He retired in 1959, but he nor Patkin was the last funnyman to be appointed by the Veeck family.

In 2004, Rick Hader – who performed under the moniker Myron Noodleman – was named Clown Prince of Baseball by Bill Veeck’s son Mike, who owns several Minor League and Independent League teams. Noodleman served as the fifth man to hold the title before passing away in 2017, but the acts that follow him today carry on the legacy to keep fans laughing.

Michael Scholl was the public relations intern in the 2008 Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program. He is an assistant athletic director at Vanderbilt University.