- Home

- Our Stories

- Different sites host rites of spring

Different sites host rites of spring

On Valentine’s Day in Dunedin, Fla., it wasn’t just love in the air as Toronto Blue Jays pitchers and catchers reported to Dunedin Stadium for the first time in 2018.

Instead, the smells of fresh-cut grass, leather gloves, sunscreen, mud-rubbed new baseballs, and crisply laundered uniforms permeated the Jays’ Spring Training complex. Just as they have every year since 1977, Toronto’s inaugural season.

The same can be said a few miles down the road in Clearwater, where the Philadelphia Phillies have spent more than 70 consecutive springs. Or about an hour away in Lakeland, where, including a brief break during World War II, the Detroit Tigers have hosted Spring Training since the mid-1930s.

It is also true in Arizona, where the New York and San Francisco Giants, have called either Phoenix or Scottsdale its spring home, with one lone exception, since 1947.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Sure, it is not uncommon for some major league teams and their Spring Training homes to share long-term connections. The Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers were virtually synonymous with Vero Beach, Fla., for 60 springs until the team moved its operations west to Camelback Ranch in Glendale, Ariz. The Pirates and Bradenton; the Mets and Port St. Lucie; the Yankees and Tampa; and the Angels and Tempe. Each February, the players and the fans come back, like swallows returning to San Juan Capistrano.

The ritual has become more-or-less routine nowadays, though some major league clubs still change Spring Training sites every so often, and more clubs have shifted to Arizona in recent years, trading in grapefruit for cacti. The variety of Spring Training locales is not what it was during the first half of the 20th century, however, when teams would opt for any kind of warm weather site, and if those sites were not available due to wartime travel restrictions, they might choose any kind of mild-ish weather site closer to home.

Yet two aspects persist: Teams will train where they are welcome, and their fans will follow.

Florida has always been a popular locale for Spring Training, but Hot Springs, Ark., could boast of being a site for numerous major league teams in the early 1900s. The therapeutic baths and spas would help ballplayers “boil out” the excesses of the offseason, while the competition would ensure a team could test itself against major league talent and not just minor league or local ballplayers.

Visiting Hot Springs in Dec. 1905 on a scouting expedition for a Spring Training site for the Cincinnati Reds, business manager Frank Bancroft provided a largely positive report:

“Since coming here, I am more than ever convinced that this is the correct place and the water certainly a boon to the players,” Bancroft said. “The idea of the players being able to obtain the famous potash Sulphur water direct from the well is of inestimable value and the distance from the city admirable for the road work necessary to the conditioning of the players.”

Despite the review and Bancroft spending “the next few days … indulging in the baths,” the Reds chose to train in San Antonio. Yet, Hot Springs remained a popular destination for ball clubs, and today, a historic baseball trail allows visitors to relive baseball memories from long ago.

Before the Brooklyn Dodgers opened their Dodgertown complex in Vero Beach in 1949, the newly integrated club opted for locales with more tropical flair. In 1947, that meant Havana, Cuba, where the Dodgers would get limber for the season. They had spent the springs of 1941 and 1942 there, as well. The trip would include exhibitions against the Yankees in Venezuela and Panama.

Perhaps one of the more entertaining ball games during that trip occurred in the swimming pool of Havana’s Hotel Nacional, The New York Times’ Roscoe McGowen reported. Teams captained by Pee Wee Reese and Eddie Stanky put on exhibition similar to baseball, using “a light rubber ball about the size of a basketball.”

Though the “contest supplied more entertainment for the spectators than any game that has been played thus far in the stadium,” the Dodgers doctor, Dr. Harold Wendler, was aghast at the spectacle, according to McGowen, noting “there are going to be some badly sunburned boys around here tomorrow. Just look at Stanky’s shoulders!”

Despite losing money on the Havana camp, in 1948, the Dodgers returned to the Caribbean, training in Ciudad Trujillo, in the Dominican Republic. This time, however, Brooklyn received guaranteed payment by the promoters. According to Branch Rickey, he had “looked all over the United States at training sites but there was something wrong with all of them.”

Throughout much of the 30-year period between 1922 and 1951, the Chicago Cubs set up camp in Avalon, on Santa Catalina Island, just off the Southern California coast. At first glance, such a location would seem an odd one, somewhat isolated from the remainder of the major league clubs, even the ones training in California or Arizona.

As it happened, in 1919, Cubs owner William Wrigley, Jr., purchased a majority share in the island and then constructed a ballpark there with the same dimensions as Wrigley Field. Though the ballpark no longer exists, the former Cubs clubhouse now functions as part of the Catalina Country Club. The Cubs returned to the mainland for Spring Training in 1952 when they were lured to Mesa, Ariz., the town where they have trained in all but 13 years since.

“Even though they were in last place most of the time, they were still a big thing for us,” Lolo Saldaña told The New York Times in 2016. Saldaña grew up on Catalina Island, where he now owns a barbershop. Locals and tourists alike would look forward to the arrival of the Cubs, who would take part in various tourist-like activities when not training.

While most of their counterparts were training in Florida and Arizona, the Angels spent many Spring Trainings at Palm Springs, Calif. Chosen by owner Gene Autry, the stadium was originally built for polo and therefore called the “Polo Grounds.” Palm Springs did host some other major and minor league Spring Trainings but nothing on a regular basis until the Angels moved in. It also lends the Angels as the answer to the trivia question: Which major league team was the only one to play home games at the Polo Grounds, Wrigley Field (the Los Angeles park that was home to the Angels in their first season in California) and Dodger Stadium (where they Angels played from 1962-65)?

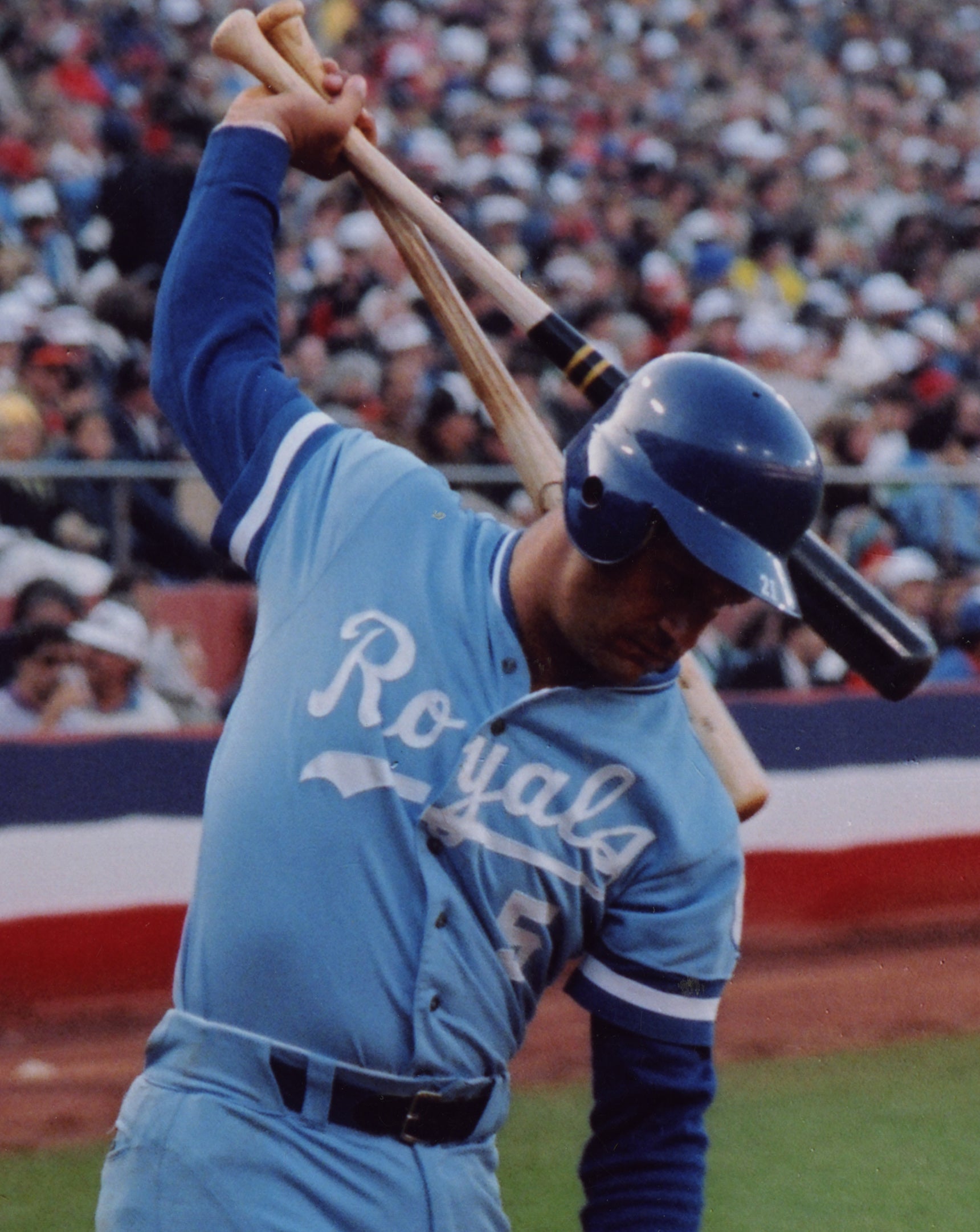

The ups and downs and back-and-forth nature of a Major League Baseball game is often compared to being on a roller coaster. In 1988, George Brett wanted to cross the roller coaster off his to-do list.

While the Atlanta Braves have spent recent springs at Walt Disney World’s ESPN Wide World of Sports Complex, the Kansas City Royals pioneered the concept of merging baseball into a theme park when Baseball City Stadium opened in 1988. Located in Haines City, Fla., the Royals’ complex – referred to as “Baseball City” – was a main feature of the Boardwalk and Baseball theme park, itself a redeveloped failed theme park, and lacking a boardwalk at that.

“I saw the thing go around a hundred times a day,” Brett told The New York Times, referring to the theme park’s Hurricane roller coaster. “I had to go on it. I’m glad I got it out of the way. It’s scary. That things flies.”

It is a good thing Brett rode the roller coaster when he did. Developed by publisher Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, the theme park wanted to attract a major league club dissatisfied with its Spring Training locale. By 1990, citing declining attendance and rising costs, new owner Anheuser-Busch closed Boardwalk and Baseball, tearing much of it down by 1993, but they and the Royals honored the 15-year contract in place. Following the 2002 season, Kansas City left for a new facility in Arizona, and not long after that, the stadium was demolished.

While many baseball fans will enjoy the action coming from the Grapefruit and Cactus Leagues this winter, for years the ballplayers and fans have flocked to points near and far, wherever there is something new or different under the Spring Training sun.

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum