Heroes, Legends Part of Game at Inaugural Hall of Fame Weekend

Even though he was surrounded on this day by a galaxy of stars, Babe Ruth always seemed to shine the brightest in the eyes of baseball fans. And so it came as no surprise when, after being honored along with the greatest stars his sport had ever known, it was the Bambino’s surprising appearance with bat in hand that brought down the house.

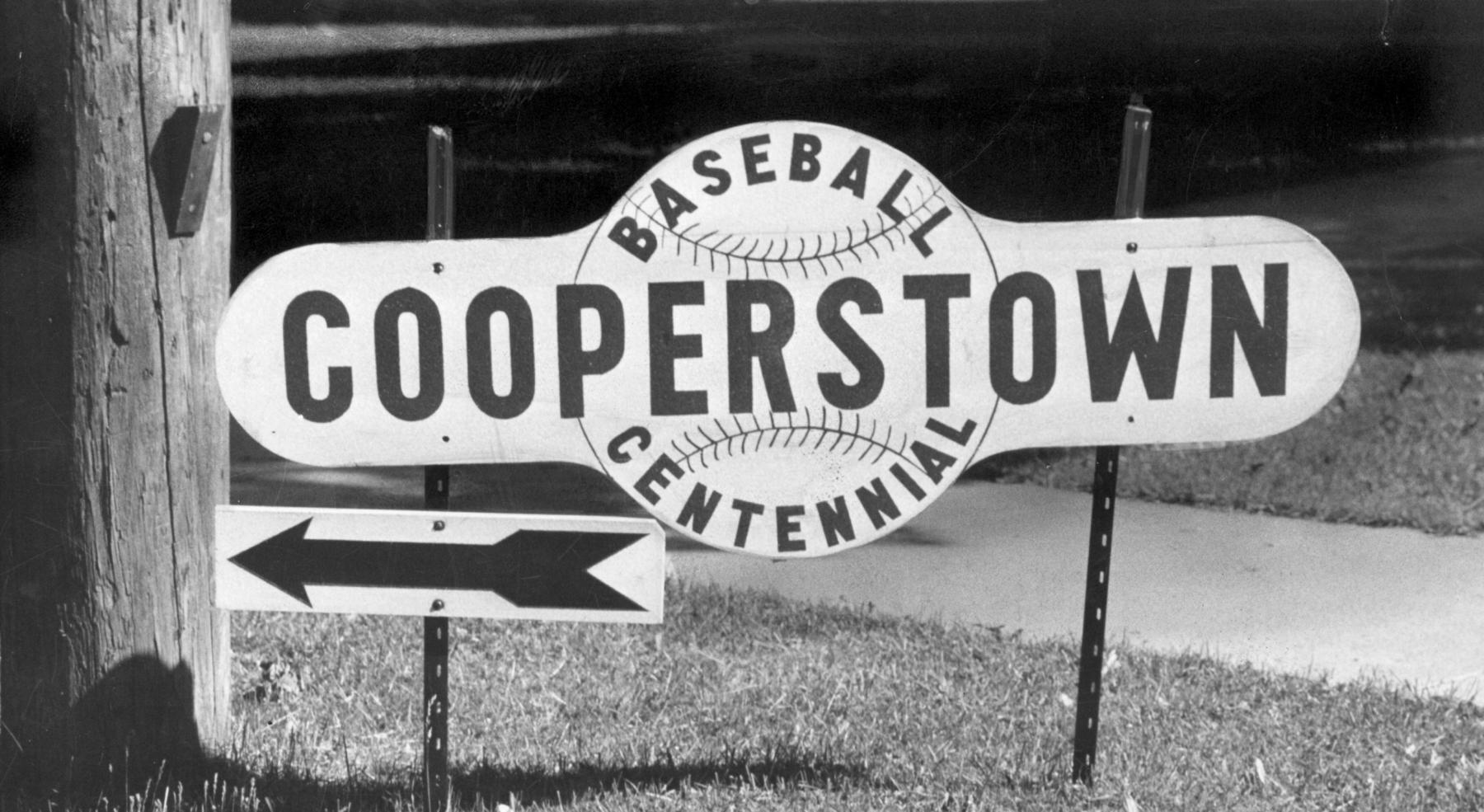

It was on Monday, June 12, 1939, when Cooperstown, N.Y., would - for at least one day - be considered the baseball capital of the world. Earlier in the day the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum would hold its first-ever Induction Ceremony in which the game’s immortals, including Ruth, would forever be enshrined. That day would also be the public opening of the National Baseball Museum, today known as the Hall of Fame.

And following the Induction Ceremony, an all-star baseball game was held at Doubleday Field, featuring the best active players of the day.

The Hall of Fame had been in the planning stages for a number of years before its official dedication and first Induction Ceremony. When the day finally came, crowds flocked to the historic village of 2,500 residents nestled in the Leatherstocking Region of upstate New York to witness the once-in-a-lifetime events that forever made Cooperstown part of the cultural landscape of our nation.

“My gosh, there were more people than cows,” marveled Catherine Walker, who was only eight years old at the time and later was a longtime Hall of Fame attendant. “I remember my dad holding me up so that I could see, putting me on his shoulders, but other than that it was just a big sea of faces.”

Howard Talbot, who would later serve as the director of the Hall of Fame, came with his family from nearby Edmeston. “For a 14-year-old it was overwhelming, believe me. No question about it.”

“I should like to dedicate this museum to all America. To lovers of good sportsmanship, healthy bodies, keen minds, for those are the principals of baseball. So it is to them, rather than to the few who have been honored here, that I propose to dedicate this shrine of sportsmanship.”

After a ruffle of drums and the sounding of taps were played for the 14 deceased members – Cap Anson, Morgan Bulkeley, Alexander Cartwright, Henry Chadwick, Charles Comiskey, Candy Cummings, Buck Ewing, Ban Johnson, Willie Keeler, Christy Mathewson, John McGraw, Charles Radbourn, A.G. Spalding and George Wright – the living inductees were introduced and approached the microphone one at a time. All except the Georgia Peach.

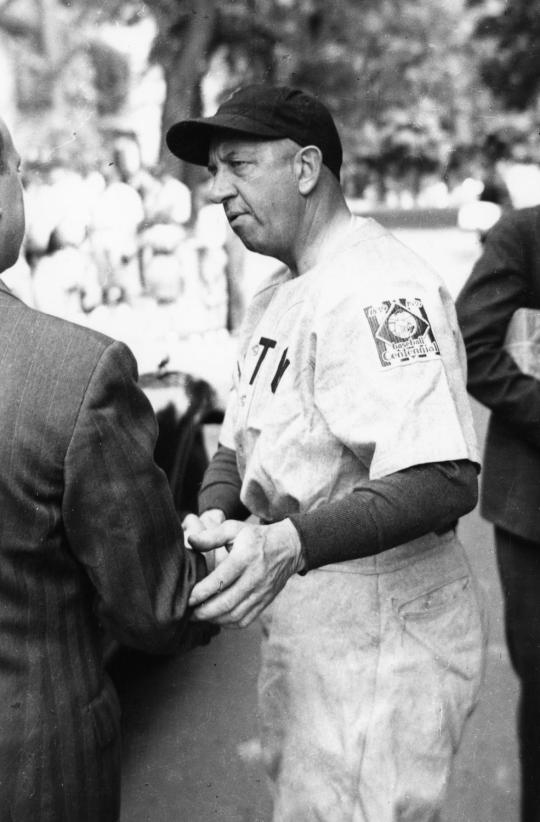

Connie Mack, Honus Wagner, Tris Speaker, Napoleon Lajoie, Cy Young, Walter Johnson, George Sisler, Eddie Collins, Grover Cleveland Alexander and Babe Ruth made short remarks for the crowd, the half dozen newsreel cameras and a nationwide radio audience; but Ty Cobb, according to reports, was delayed because he was overcome with indigestion en route to Cooperstown and had to stop off at a hospital in nearby Utica.

“I was washing up over at Knox College,” said Cobb, “the only place in Cooperstown where I could get accommodations – when I heard my name read over the radio. I didn’t know the ceremonies began that early.

“Called out on strikes, I guess,” he laughed.

While Cobb was tardy, Sisler decided to stay in Cooperstown and send his wife to attend their son George Jr.’s graduation ceremony from nearby Colgate University.

Some of the Hall of Famers, like longtime second baseman Collins, were awestruck by the talent on the Cooperstown stage: “I’d be glad to be the batboy for such a team as this.”

Alexander, winner of 373 big league games, said during his speech, “In my dreams I often think what I could do today with a team like they were and if they could be now what they were then. I would have no mistakes to be worrying about or when they hit those line drives off me I would have no trouble wondering who was going to get them.”

The last player introduced was Ruth, who it was reported received the day’s loudest cheers.

“I hope some day that some of the young fellows coming into the game will know how it feels to be picked in the Hall of Fame,” Ruth said. “I know the old boys back in there were just talking it over, some have been here long before my time. They got on it, I worked hard, and I got on it. And I hope that the coming generation, the young boys today, that they’ll work hard and also be on it.

“And as my old friend Cy Young says, I hope it goes another hundred years and the next hundred years will be the greatest.”

Also attending this day was longtime American League umpire Tom Connolly, himself elected to the Hall of Fame in 1953, who was impressed with the improved verbal skills of the former players.

“The way those fellows have improved their vocabularies was something to hear. They walked right up to those radio microphones and started unloading words like ‘magnificent,’ ‘superb,’ ‘imposing’ and ‘stupendous,’” he said. “They sounded wonderful except they didn’t sound like the same fellows I used to know when they were playing baseball and I was umpiring.”

The day’s events continued that afternoon with a four-block parade down a flag and bunting decorated Main Street to Doubleday Field, where a pageant, the “Cavalcade of Baseball,” was held. It began with demonstrators appropriately dressed showing how the game evolved from its townball beginnings in the 1830s to the days of its first organized teams in the 1850s and concluded with a game played between the current stars of the game.

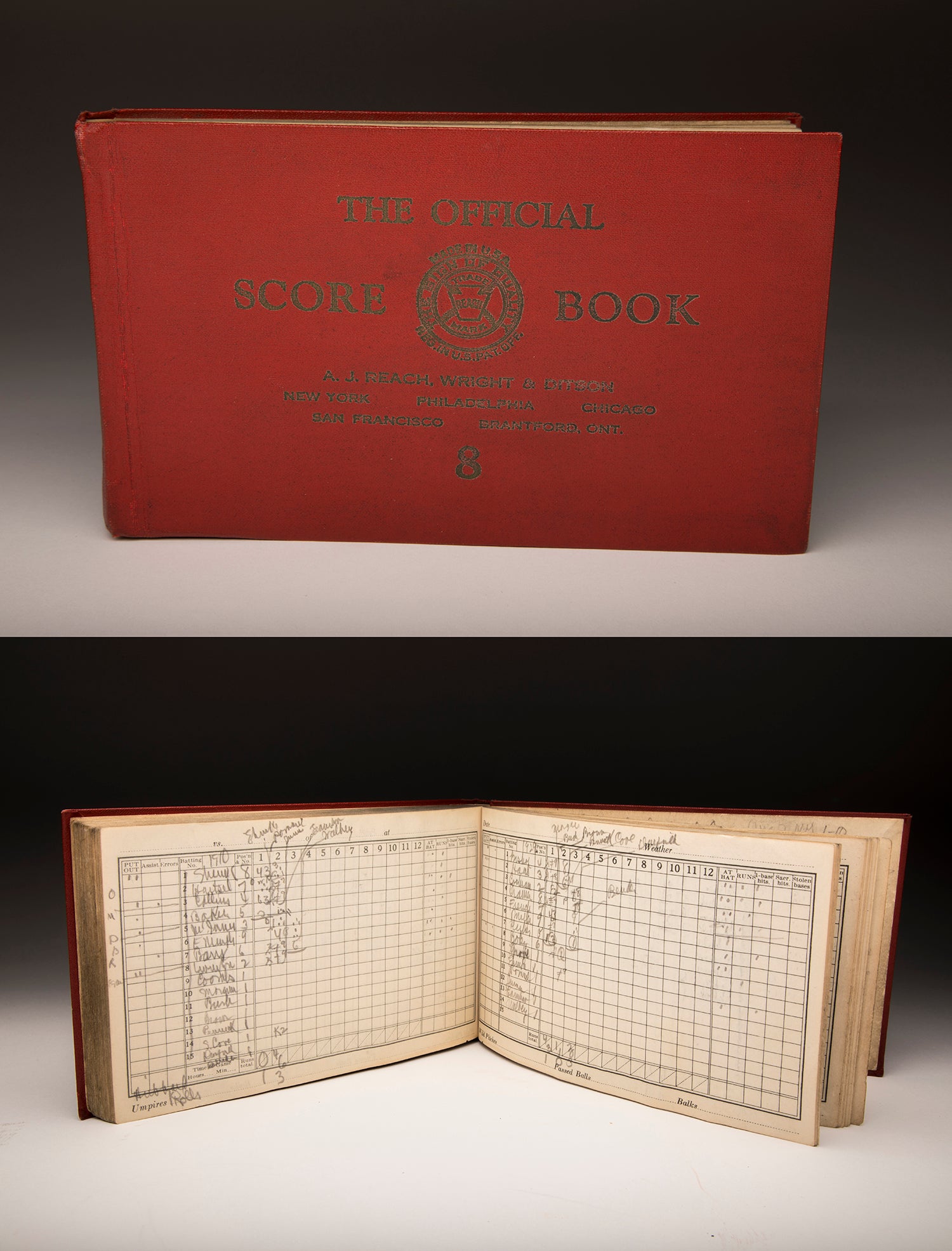

With the 16 big league parks closed for the day and each club represented by two players, Hall of Famers Wagner and Collins chose up sides using the hand-over-bat method of getting the first selection. “I don’t know about the other fellows, but I’m playing for keeps, to win,” Wagner was heard to say before the game. “I’m not playing for marbles.”

The two Hall of Famers picked their teams from among such future inductees as Dizzy Dean, Mel Ott, Hank Greenberg, Lloyd Waner, Charlie Gehringer, Billy Herman, Arky Vaughan, Joe Medwick and Lefty Grove. Other participants of note included Stan Hack, Cecil Travis, Johnny Vander Meer, Wally Moses, Terry Moore, Moe Berg, Muddy Ruel and Cookie Lavagetto.

“It was quite something that here in Cooperstown we could see some of the heroes of baseball and were able to say ‘hi’ to them,” said Homer Osterhoudt, who as a 21-year-old documented the day’s activities with approximately 50 photographs that are now part of the Museum’s permanent collection.

And while the Wagners would come away with a 4-2 triumph over the Collins team, it was the dramatic “comeback” of Ruth, pinch hitting for Danny MacFayden against Syl Johnson in the bottom of the fifth inning, that is most remembered.

The Glimmerglass, Cooperstown’s summer daily newspaper, reported that, “Everyone was pulling for the Babe to pump one into the stands but the best the Bambino could do was pop a two-two pitch up the first base line which (catcher Art) Jorgens caught. The Babe returned to his place in the dugout with the cheers of the fans still ringing in his ears.”

According to Harold Hollis, who covered the game as a 24-year-old reporter for the local Cooperstown newspaper, “Everybody yelled, ‘Drop it, drop it, drop it,’ because they wanted to see him hit one out.”

Ruth, four years retired from the game, later admitted, “I’m too old…I can’t hit the floor with my hat.”

But after the game, Ruth's legendary goodwill was in evidence as he agreed to pose for a photo for 14-year-old Fred St. John.

“He said, ‘Wait a minute, I think you’ve got your finger on the lens,’” St. John recalled. “He got me all lined up and he said, ‘Now point it and take a deep breath and hold still and then shoot it.’ And so I did and he said, ‘There, I don’t’ want anybody to take a bad picture of me.’”

Bill Francis is a Library Associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum