- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: The simple brilliance of Clyde Sukeforth

#GoingDeep: The simple brilliance of Clyde Sukeforth

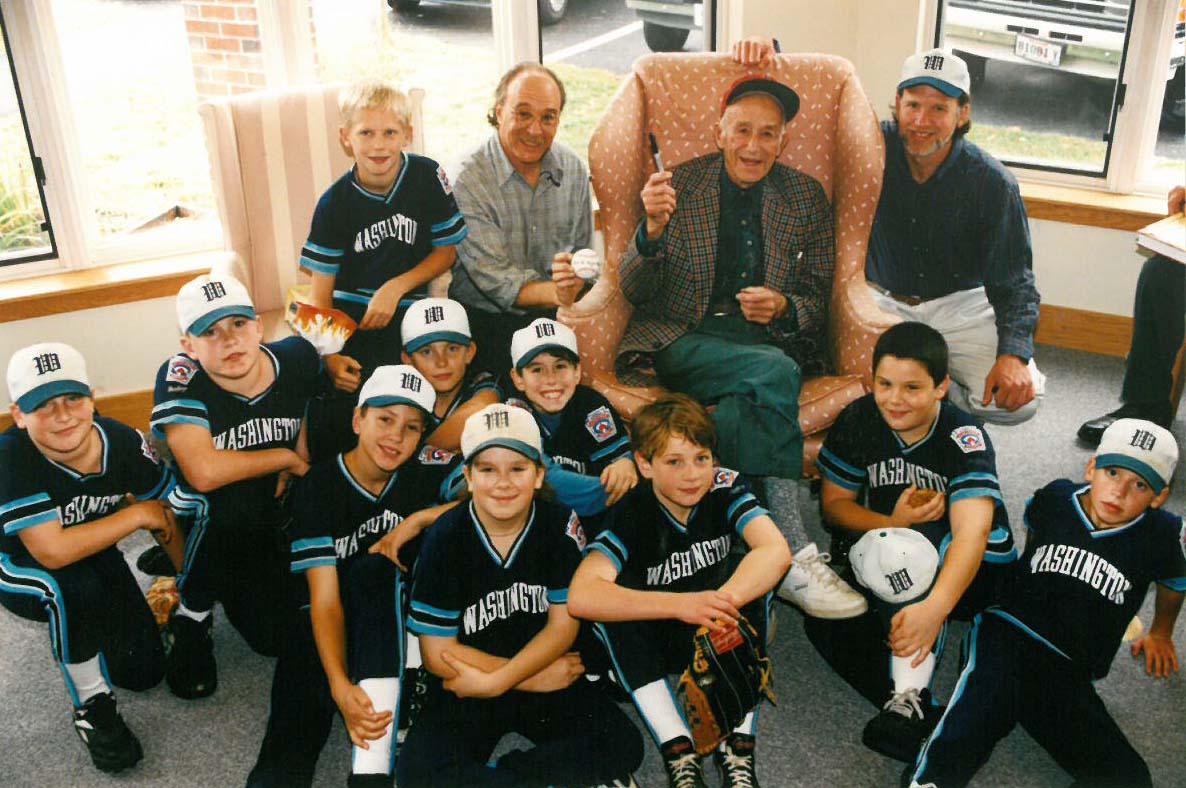

Ninety-three-year-old Clyde Sukeforth, donning a plaid blazer and a red baseball cap, slowly walked past an exhibit in Gibbs Library. A 2,500 square foot brick building, Gibbs serves as the focal point of its small but passionate community, bringing authors, performers and others of “local interest” to the coastal town of Washington, Maine.

After 48 years in the big leagues, Sukeforth undoubtedly fell into the “local interest” category. As he gazed up at dozens of black-and-white photographs of himself adorning the walls, he incredulously posited a question: “Why are you bothering with a second-string catcher?”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

For anyone who knew Sukeforth, or has listened to his interviews, this reaction shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise. The former backstop was self-effacing to his core, dodging compliments like they were wild pitches. But whether he thought he deserved an exhibit at Gibbs Library or not, one fact remains indisputable: Clyde Sukeforth was much more than a backup catcher.

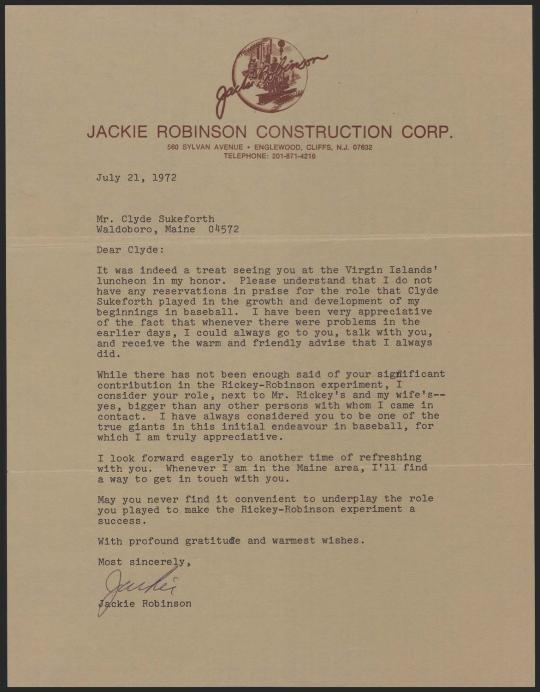

If you need further proof, just ask Jackie Robinson. In 1972, the year of his passing, the baseball pioneer wrote to the man who first scouted him:

“Please understand that I do not have any reservations in praise for the role that Clyde Sukeforth played in the growth and development of my beginnings in baseball. I have been very appreciative of the fact that whenever there were problems in the earlier days, I could always go to you, talk with you, and receive the warm and friendly advise that I always did.

“While there has not been enough said of your significant contribution in the Rickey-Robinson experiment, I consider your role, next to Mr. Rickey’s and my wife’s – yes, bigger than any other persons with whom I came in contact. I have always considered you to be one of the true giants in this initial endeavor in baseball, for which I am truly appreciative.”

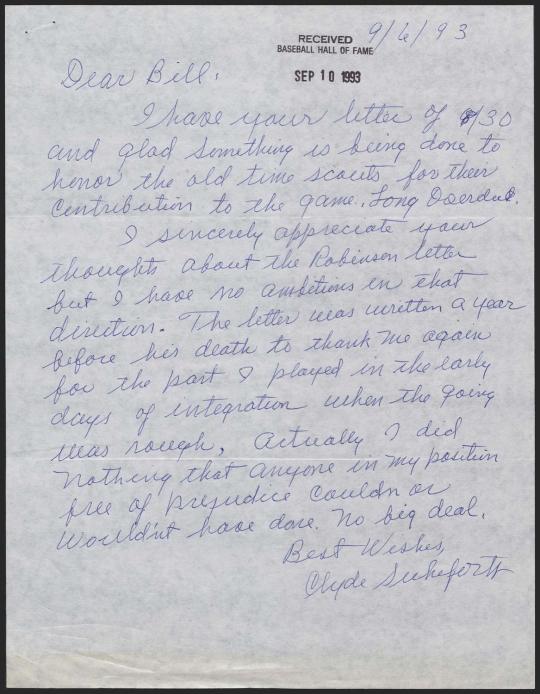

That letter is now preserved in Cooperstown at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, along with Sukeforth’s response to it, years later, in a note to a friend:

“I sincerely appreciate your thoughts about the Robinson letter, but I have no ambitions in that direction. The letter was written (the year of) his death, to thank me again for the part I played in the early days of integration when the going was rough. Actually, I did nothing that anyone in my position, free of prejudice, couldn’t or wouldn’t have done. No big deal.”

Needless to say, it was a big deal. But before Sukeforth and Robinson could face the challenges that 1947 would bring, the “second-string catcher” had to earn his own cup of coffee. And that story brings us back to Washington, Maine.

Clyde Leroy Sukeforth was born on Nov. 30, 1901 to Pearle and Sarah Sukeforth. He grew up on a farm, and attended a one-room schoolhouse throughout high school. He and his sister, Hazel, would walk to school every morning – three and a half miles, each way – until Clyde transferred to the Colburn Classical Institute in 1916.

Although Washington was hundreds of miles away from the closest big league ballpark, baseball was an integral part of Sukeforth’s childhood.

“As a kid, we played baseball seven days a week, practice or games. In those days, football wasn’t too attractive, basketball didn’t mean much unless you were 7-feet-tall,” he told the Sport Collectors Digest. “When I was a kid I remember standing by the stagecoach, waiting for it to come through with the morning edition of the Boston Post, and the first thing I did was I opened it up to read about the Red Sox.”

His love of the game – and prowess behind the plate – only grew stronger as the years passed, and eventually earned him a spot at Georgetown University.

“After World War I, baseball was at its peak,” Sukeforth told the Hall of Fame in 1995. “All the industries supported ballclubs getting high school and college players and semi-pros. I was playing for the Great Northern Paper Company. The team was mostly Georgetown players. They had a catcher who had signed with the New York Giants and they asked me to play catcher.”

After two years in Washington, “Sukey” signed with the Cincinnati Reds, for $600 and a $1500 bonus. Making only one plate appearance in 1926 – a strikeout – he was sent back down to Double-A for the rest of the season. But the rookie learned quickly, and by 1929 was the Reds’ starting catcher.

Unfortunately for Sukeforth, a tragic shot-gun accident in 1931 would impair his eyesight, prompting a trade in 1932 that would ship future Hall of Famer Ernie Lombardi to Cincinnati and Sukeforth to the Dodgers. Though he’d only play three seasons for Brooklyn – aside from an astounding 18-game stint at catcher at the age of 43 in 1945, during the player shortages of World War II – the trade marked the beginning of a partnership between Sukeforth and future Hall of Famer Branch Rickey that would shape the course of baseball history in more ways than one.

Sukey would then embark on a seven-year managerial career in the minor leagues, taking over the Dodgers’ Double-A-farm team in Montreal in 1939. His teams never had a losing season, and won better than 55 percent of their games. On March 1, 1943, Rickey brought him back to Brooklyn as a coach, and a couple of years later, as a scout.

He came with “a box of about five dozen smelt which he had caught through the ice along the coast near his home,” Rickey said to The New York Times. “That’s why he got the job.”

The Dodgers executive, determined to be the first to tap into this untouched pool of talent, had his scouts milling around the Negro Leagues as early as 1943.

“We made ourselves low-key. When you had white scouts at colored ballgames, people asked a lot of questions,” Sukeforth told the Maine Times. “There was a black team in Brooklyn – the Brooklyn Brown Bombers – and we were allowed to say we were scouting for them.”

But Robinson was different. This time, Rickey opted for a different approach.

“We normally did not announce our presence to the teams or players,” Sukeforth said to the Hall of Fame. “When he sent me to see Jackie, he told me to identify myself. Up until that time, we made ourselves inconspicuous.”

At this point, Sukeforth was the last Dodgers scout to see Jackie. Tom Greenwade, the scout who would later bring Mickey Mantle to the Yankees, was among those who had paid Robinson a visit. But this was a delicate situation, and Rickey needed a scout with sensitivity to make contact. So he chose Clyde.

“It didn’t matter to me whether a fellow was red, yellow, black, or green,” Sukeforth said in an interview years later. “If he was a prospect, he was a prospect. Mr. Rickey felt the same way.”

Sukeforth probably told the story of his first encounter with Jackie in 1945 hundreds of times. So much so, that it sounds nearly identical in all of his interviews:

“[Rickey] called me in and he said ‘I want you to go to Chicago on Friday, and see a game between the Kansas City Monarchs and the Lincoln Giants,’” he told the Hall of Fame. “’Pay particular attention to a shortstop named Robinson. Especially his arm. Tell him who sent you.’ He comes out with a couple of other boys and I hailed him. I delivered my message. He was thunder struck. He couldn’t conceive why Mr. Rickey was interested in him or his arm.”

Even without hearing his voice, you can sense the unembellished way Sukeforth relays this narrative. But as was usually the case with Clyde, his involvement behind-the-scenes played a bigger role than he led on. For one, the scout knew Robinson was a terrific athlete, but wasn’t able to see him play that day because he was recovering from a shoulder injury. He brought him back to New York anyway, in what seems in retrospect to be a scouting of a man’s character more than anything.

After the game, they met at Chicago’s Stevens Hotel to speak further about Mr. Rickey’s proposition. Sukeforth had another upcoming assignment in Toledo, so Robinson would meet him there after the Monarchs’ series had ended.

“We took a train to New York, rode overnight,” Sukeforth said to the Associated Press. “That morning I took Robinson into the old man’s offices and the old man really gave him a grilling.”

No mention was made of the two dollars Clyde paid the operator that night to allow Jackie to ride the whites-only elevator with him to his room. Or of the fact that Clyde sat alongside Robinson from Toledo to New York in the Pullman sleeper car, assuaging his concerns about integrating the big leagues for hours. In Sukeforth’s eyes, he was just doing his job. Nothing more, nothing less.

“I get a lot of credit I don’t deserve,” he told Baseball Research Journal in 1987. “I treated Robinson just like any other human being. See, coming from Maine, I never thought about color. I don’t feel I did anything special. I was just there.”

Rickey and Robinson met on Aug. 28, 1945. By October of that year, Robinson was signed for a $3,500 bonus and $600 a month to play with the Dodgers’ affiliate in Montreal, the Royals. He debuted in the big leagues on April 15, 1947 – with none-other than Clyde Sukeforth serving as interim manager – and broke the color line, opening the door for countless African-American ballplayers to come.

“The pressure Robinson was under that day, oh my God,” Sukeforth said to Sports Collectors Digest. “Just put yourself in his position, with the future of a million Blacks resting on your shoulders. The ordinary man would be under great pressure just because it was Opening Day of the season. But having to break a color line, and in the process change the course of baseball – Robinson was really something special.”

Jackie Robinson would remain with the Dodgers through 1956, but Branch Rickey left before then, becoming the Pittsburgh Pirates’ general manager in 1950. Clyde followed him there in 1952.

Two years later, Rickey sent him on to Richmond to scout Joe Black, on the Dodgers farm team.

Sukeforth came back with a draft recommendation, just not the one Rickey had foreseen.

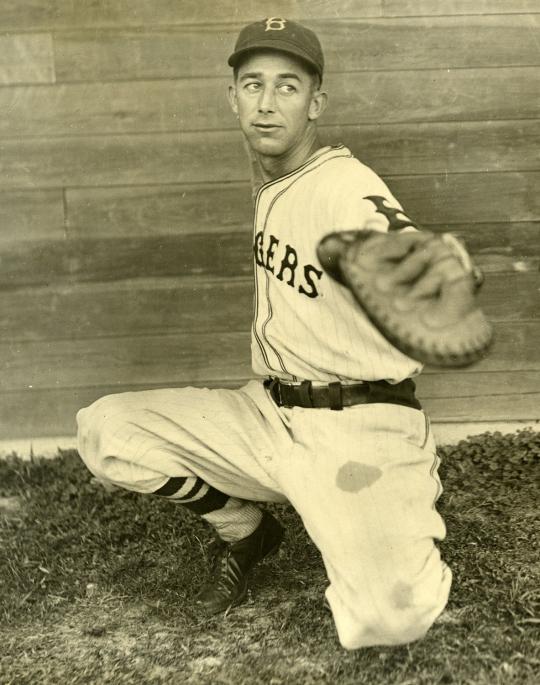

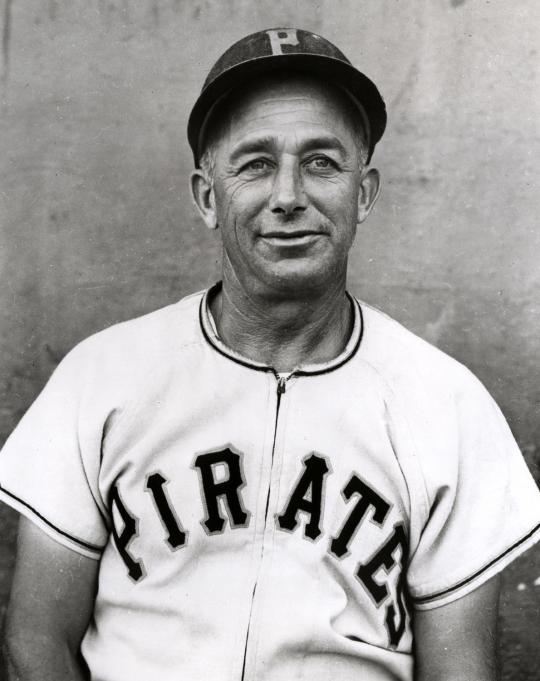

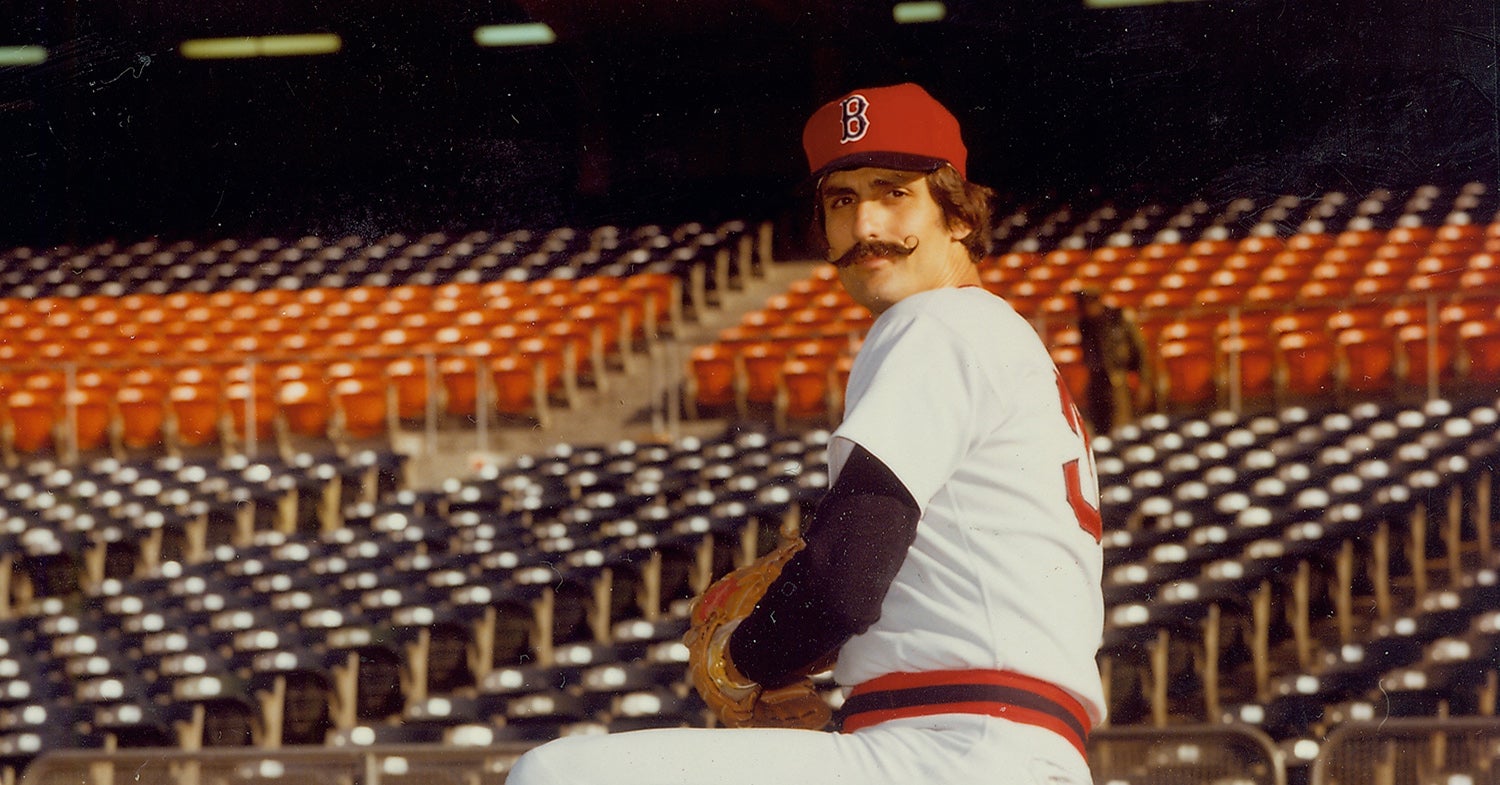

Clyde Sukeforth was traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1932 to serve as a backup catcher for future Hall of Famer Al López. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

The letter Jackie Robinson wrote to Clyde Sukeforth in 1972 is currently preserved at the Hall of Fame. Robinson wrote the letter three months before he passed away. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Clyde Sukeforth's letter, in which he addresses Jackie Robinson's 1972 note, is currently preserved at the Hall of Fame. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

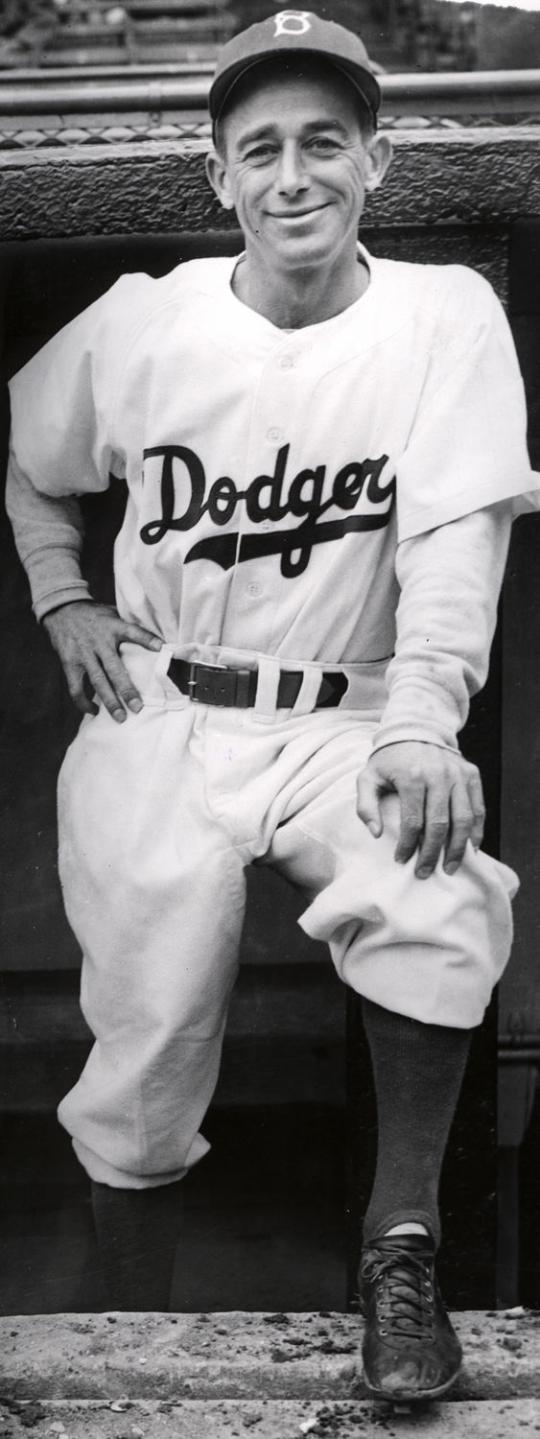

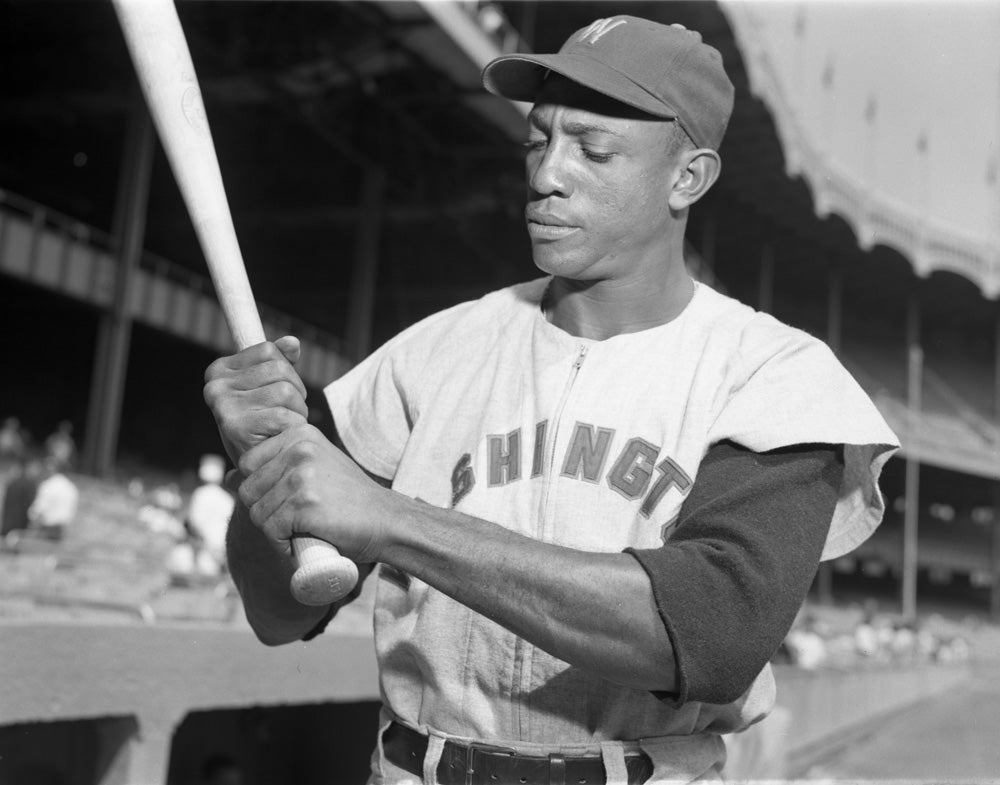

Clyde Sukeforth was a player, scout and coach for the Brooklyn Dodgers for over 30 years. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

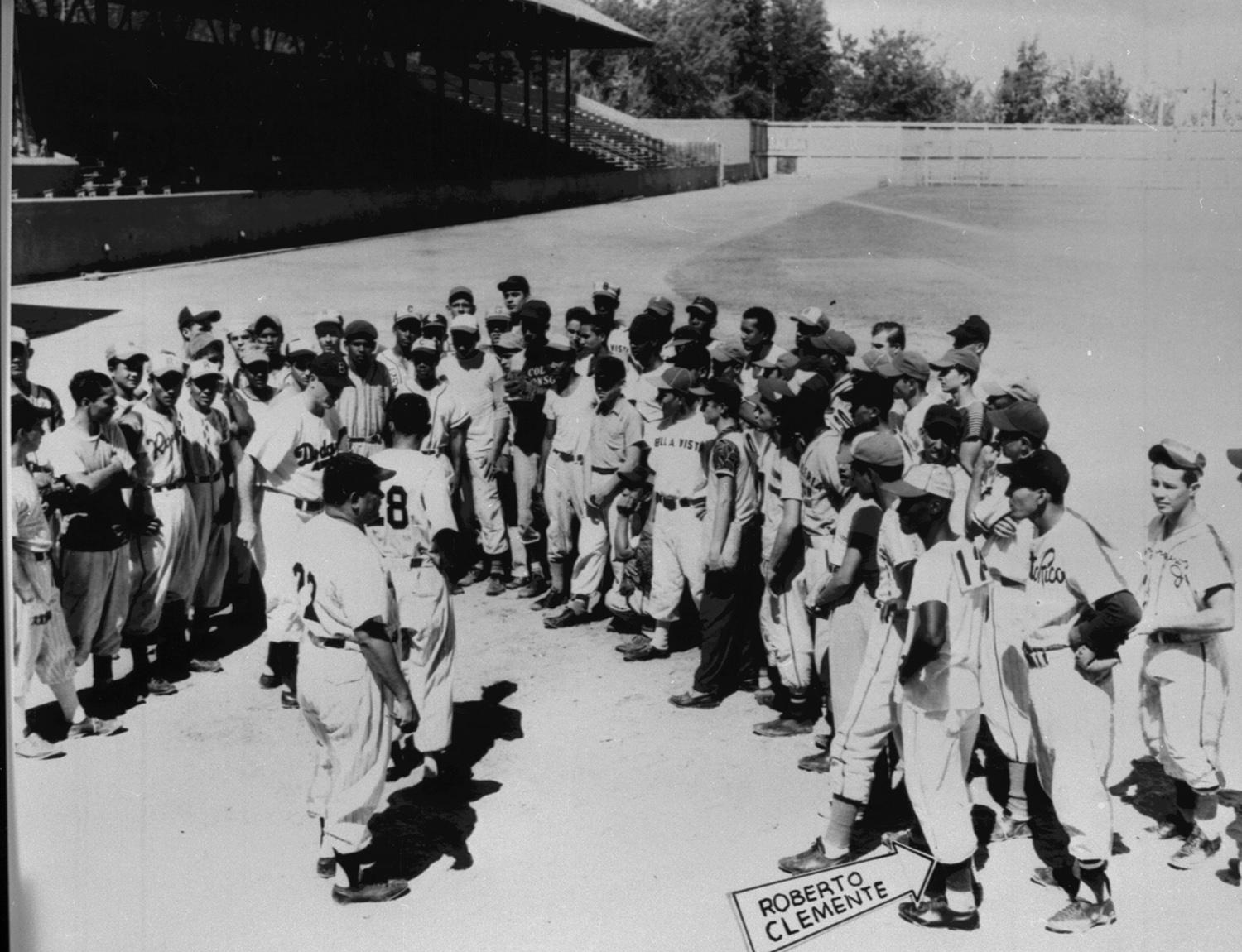

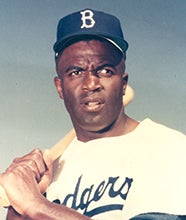

Jackie Robinson (left) signed a contract with Branch Rickey’s Dodgers organization in 1945. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

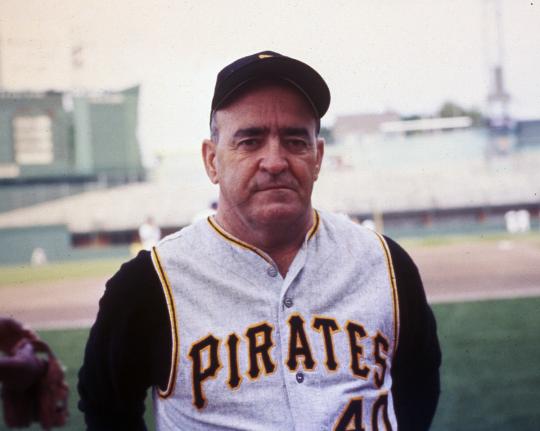

Clyde Sukeforth was a scout for the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1954-1966. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Among Clyde Sukeforth's contributions to the Pirates during his time as a scout included recommending Danny Murtaugh (pictured above) as manager of the team. Murtaugh would lead the Bucs to two pennants and two World Series titles. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

“The Royals had this baby-faced Negro in right field,” he told Sports Collectors Digest. “They were having their infield and outfield practice and here was this kid out there – with a real great arm. You couldn’t help noticing that. He wasn’t playing, though. Max Macon was the manager, and Max had played for me in Montreal. In the seventh inning the Royals are behind and who should go up to pinch hit? This boy in right field. I didn’t even know what his name was then; I didn’t have any batting order. He hit a routine ground ball to shortstop and the play at first base was bang-bang. I mean, they just got him. So he’s showed me he could throw and run, right then. The next four nights I was out there watching him in batting practice. His form was a little bit unorthodox but he had a pretty good power stroke. So I wrote Mr. Rickey and I said, ‘Joe Black hasn’t pitched, but I have you a draft choice.’”

The Pirates finished last by a big margin the season before, so Pittsburgh had the first choice in that winter’s Rule 5 Draft. Sukeforth knew who his first choice would be. But when he got back to Pittsburgh, he received some pushback from fellow scouts.

“One of the scouts had a candidate—an infielder in the Southern League – and another one had a pitcher someplace else,” Sukeforth said. “Mr. Rickey asked, ‘Do you have a candidate, Clyde?’ and I said, ‘Yeah, Clemente with Montreal.’

"‘Any of the rest of you fellows seen Clemente?’"

“One fellow said, ‘I did. I didn’t like him.’”

“’What didn’t you like?’”

“’Well,’” he said, “’He wasn’t playing for one thing and I didn’t like his arm.’”

“I didn’t say anything. I didn’t want to embarrass the guy, but I knew very well he didn’t get a look at the arm. The boy may have been pouting or something because he wasn’t playing. I told him afterwards, ‘You didn’t see his arm. He probably just didn’t feel like throwing, but don’t think he can’t throw.’”

“Well, you’ve got one guy that says he’s got a great arm, another guy who doesn’t like it. First choice is very important to us, so he sent George Sisler and Holly Hague to Montreal to see him. Naturally, we drafted him. For $4,000, it wasn’t bad deal.”

Finding two Hall of Famers in a 10-year span is akin to winning the lottery twice in a lifetime. But years after Clemente and Robinson earned their bronze plaques, Sukeforth maintained his assessment of himself as the middleman – and nothing else.

“I don’t know. I am not a good scout,” he told the Hall of Fame. “I can just pick out the Hall of Famers. The guys that I picked out, anyone would have picked out. The good scouts can see something in attitude, movement. I have missed major leaguers without even reporting on them.”

Sukeforth remained with the Pirates for a couple more years, making more influential decisions along the way – among them, recommending Danny Murtaugh as skipper of the Bucs in 1957 (“Rickey thought that Murtaugh couldn’t handle players. I talked him out of that.”). He retired in 1966 and moved to Waldoboro, Maine, where he picked up life right where he left off: Chopping wood, fishing, and following the Red Sox.

Sukey was inducted into the Maine Baseball Hall of Fame in 1969, and the Midcoast Sports Hall of Fame in 2007. Three years later, Prescott Memorial School opened Clyde Sukeforth Field, which continues to host Little League teams to this day.

On Sept. 3, 2000, Clyde Sukeforth’s 98-year journey ended only 13.1 miles from where it began, on Old Broad Bay. No services were held, per his request. The “second-string catcher” wouldn’t have it any other way.

“I don’t ask for a lot out of life, but I do want contentment,” Sukeforth said. “I could never find it as a manager. I have a happy home life, own a farm in Waldoboro, Maine, and among other things I grow up there are Christmas trees. It doesn’t get any better than this.”

Alex Coffey is the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum