The Ted Williams Thread

According to “The Baseball Dictionary,” “Sweet Spot” is defined as either:

1) The most desirable spot on a single-signed baseball, the section of a baseball reserved for the team manager to autograph; or 2) the section on the barrel of the baseball bat where the ball most likely can be hit solidly and for maximum power, giving it the best ride.

With apologies to Paul Dickson, who compiled that invaluable resource, baseball has a third meaning to the phrase, one that might be described as the serendipitous blending of time and place and people. A “sweet spot” happens every once in a while, but perhaps the best example of just such an event came on June 12, 1939, some 85 years ago, when the National Baseball Hall of Fame opened its doors in Cooperstown, N.Y., to help commemorate what was celebrated as the sport’s 100th anniversary.

By all accounts, it was a splendid affair. Some 12,000 people filled the streets of the idyllic town perfectly positioned at the tip of Otsego Lake to be the home plate of baseball. They came to visit the Hall of Fame itself, built the year before for $100,000, to honor the first legends to be inducted and to watch an all-star game of current players play on Doubleday Field.

According to Francis E. Stan of the Oneonta Star: “Practically everybody who is anybody in baseball was there.” Stan described the opening of the festivities this way: “Early in the morning the first passenger train in seven years chugged laboriously up the steep slope to the edge of Otsego Lake, or Glimmerglass, and poured forth the great of today and yesterday… Honus Wagner and Walter Johnson, Carl Hubbell and Ducky Medwick, Cy Young and Ty Cobb, Johnny Vander Meer and Tris Speaker, Charlie Gehringer and Nap Lajoie and all the rest.”

The year itself was a Pullman car on the train of history. It was not only the rookie year for the Hall of Fame, but also for Little League Baseball, which began as a three-team league in Williamsport, Pa., some 200 miles southwest of Cooperstown. It also marked the debut of televised major league baseball, which began with famed broadcaster Red Barber calling an Aug. 26 doubleheader between the Cincinnati Reds and Brooklyn Dodgers at Ebbets Field — future Hall of Famers Ernie Lombardi and Leo Durocher played in it. One day earlier, "The Wizard of Oz" opened and America soon heard the Munchkins sing to Dorothy that she would be “a bust in the Hall of Fame.”

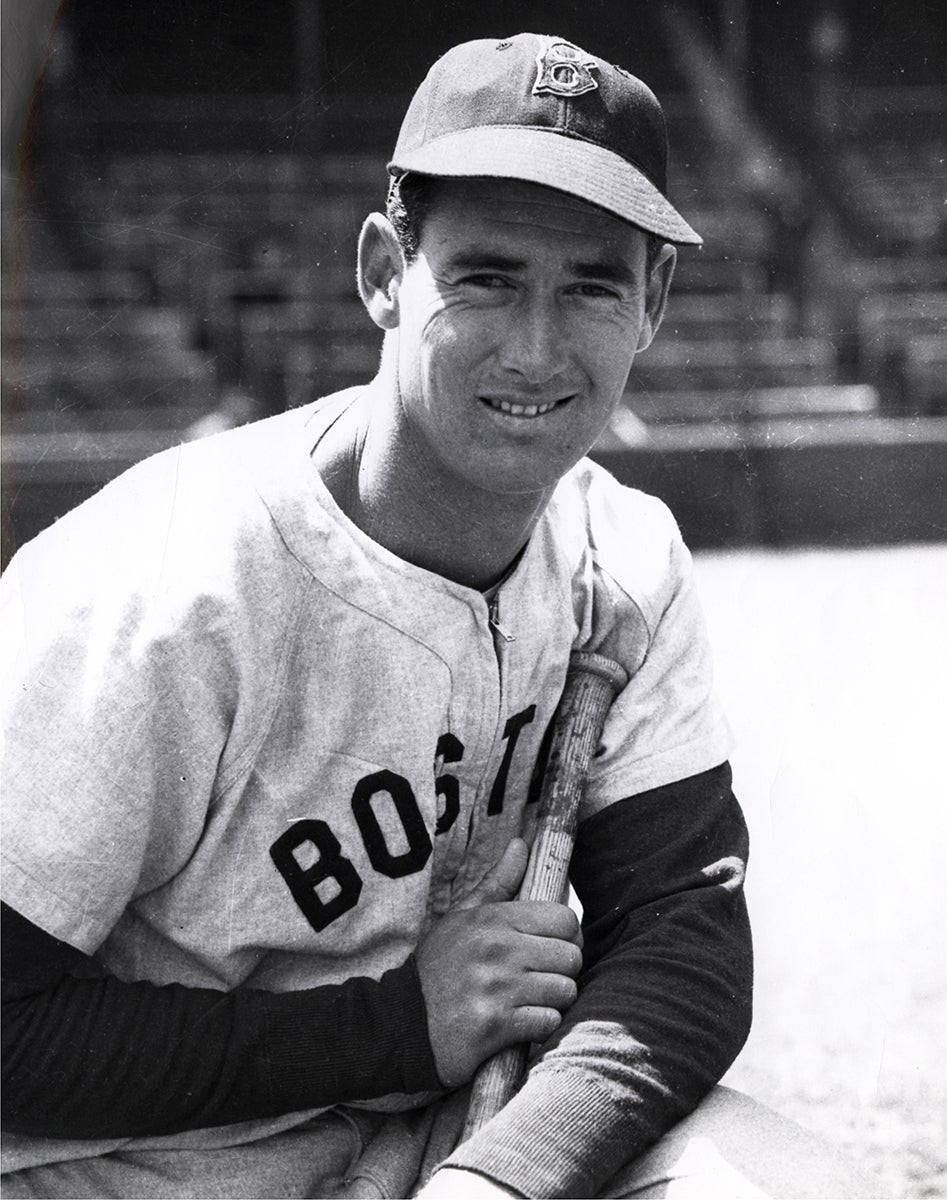

There was another rookie that year, one who would change baseball and the Hall of Fame itself. He was Theodore Samuel Williams, a 20-year-old outfielder for the Boston Red Sox, and before he was through, he came to define excellence, valor and charity. He was the talk of baseball in 1939, and 85 years later, he’s still a topic of conversation.

Call to mind the iconic photo in the Museum of the 10 living Hall of Famers who were photographed on a platform for the first Induction Ceremony. Connie Mack, seated between Babe Ruth and Cy Young, had said of Williams that April, “It wouldn’t surprise me if he becomes another Babe Ruth. I never saw anything like it.” Grover Cleveland Alexander, standing second from the left, remembered Williams homering off him in San Diego when Old Pete was on a barnstorming tour and “The Kid” was only 15. As for the man in the last seat to the left, Eddie Collins, well, he knew about “The Splendid Splinter” as well as anyone.

After the second baseman’s brilliant career with the Philadelphia A’s and Chicago White Sox (3,315 hits, 741 stolen bases), Collins became the general manager for the Boston Red Sox, owned by his prep school pal, Tom Yawkey. It was while on a scouting mission to the West Coast to check out San Diego Padres second baseman Bobby Doerr in 1937 that Collins first laid eyes on Williams when he was called on as a pinch-hitter against Portland.

As chronicled in Ben Bradlee Jr.’s “The Kid,” itself a splendid 2013 biography, Collins recalled: “I looked down on the field and nearly broke out laughing when I got a peek at the gawky bean pole who was striding toward the plate. But I didn’t laugh when I saw him swing at the ball and line a double over the first sacker’s head… There was something about the way he tied into the ball which all but shocked me out of my seat.”

When Collins went to the owner of the Padres, Bill Lane, to tell him he was interested in Williams, Lane thought he was kidding. But as Collins later told Williams, who told the story to Bob Costas in 1993: “All I thought about when I saw you out there was Joe Jackson.” And as Williams added, “That was a helluva compliment because there never was a better hitter in history than Joe Jackson.”

Williams would hit .327 with 31 homers and a league-leading 145 RBI as a rookie. He finished fourth in the Most Valuable Player voting behind Joe DiMaggio, Bob Feller and teammate Jimmie Foxx. And the Sox even agreed to his suggestion that the right field fence be shortened from 402 feet to 380.

Baseball courage is one thing. Fighting for your country is another. After hitting .406 in 1941 and winning the Triple Crown in 1942 (.356, 36 homers, 137 RBI), Williams signed up for the Navy’s V-5 program to begin training as a pilot. He was a natural at that, too, becoming so proficient at gunnery that he became an instructor, training other Marine pilots. While he occasionally played in games for service teams, three years is a long time to be out of baseball. Nobody knew quite what to expect when he made his return on Opening Day of the 1946 season, April 16, in front of none other than President Harry Truman.

The answer came soon enough. With two outs and none on in the third inning, he hit a towering blast off Roger Wolff, and the Red Sox went on to win the game, 6-3. They would win their first five games, in fact, on their way to capturing their first American League pennant since Ruth played for them in 1918.

On June 26, 1946, the Red Sox played a Wednesday doubleheader against the Tigers in Briggs Stadium. Among the 41,002 people in attendance that day was a 7-year-old boy from Zeeland, Mich. “It was my very first time at a major league park,” said Hall of Fame pitcher Jim Kaat. “My father and I got to see Ted Williams hit two home runs, one in each game. We also got to see Hank Greenberg hit two out, Hal Newhouser throw a complete game and Bobby Doerr play second base.

“To think that one day I would be joining them in the Hall of Fame. Or that, much less, 13 years later, I would be pitching to Ted Williams.”

Williams would go on to win his first MVP award that season. But in a tune-up exhibition before the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, Williams injured his elbow and ended up hitting just .200 with one RBI as the Red Sox lost in seven games — the only World Series of his career.

He had another Triple Crown year in ’47 and won a second MVP in ’49. But then Uncle Sam called again, this time for the Korean War. The Marines needed seasoned pilots, and Williams, a captain in the Reserve, was asked to report for active duty on May 2, 1952. In his last game on April 30, he hit a two-run homer off the Tigers’ Dizzy Trout.

After training in jet aircraft, Williams was dispatched to Korea to fly on dive-bombing missions. On one such mission, he had to crash-land his plane after it was hit and escaped just before it burned to a crisp. Yet he was back in another plane the next morning.

A series of ear infections consigned him to sick bay, and not long after that he was sent back to the States, just in time for the 1953 All-Star Game in Cincinnati, where he threw out the first ball. Soon enough, he was swinging a bat again, hitting .407 in 91 at-bats.

He played through the 1960 campaign. The best way to sum up Williams’ last season, and indeed his career, is to turn it over to John Updike, who described his final plate appearance thusly in his classic New Yorker piece, “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu”: “Like a feather caught in a vortex, Williams ran around the square of bases at the center of our beseeching screaming. He ran as he always ran out home runs — hurriedly, unsmiling, head down, as if our praise were a storm of rain to get out of. He didn’t tip his cap. Though [the crowd] thumped, wept and chanted ‘We want Ted’ for minutes after he hid in the dugout, he did not come back… The papers said that the other players, and even the umpires on the field, begged him to come out and acknowledge us in some way, but he never had and did not now. Gods do not answer letters.”

He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1966. But he kept on making history. Another of his gifts to the game was “The Science of Hitting,” written with John Underwood, in 1970.

“It was my bible,” said Hall of Famer Wade Boggs. “So you can imagine the thrill I felt when I’m a Red Sox minor leaguer standing in line for a movie in Winter Haven (Fla.) when I see that Ted is standing a couple of places behind me. I go up to him, introduce myself and he asks, ‘Can you hit?’ And I said, ‘Yes, I can, thanks to you.’”

After his induction in ’66, Williams did not return to Cooperstown until 1980, when Jean Yawkey asked him to come back and make the induction speech for her late husband. Then she made him promise to come back every year, and before too long, Williams became the patron saint of the Hall of Fame. One Induction morning, Williams left the Otesaga Hotel at 7 a.m. to go fishing and saw a long line of fans. He asked one of them what they were waiting for, and when the fan said, “You, Mr. Williams,” Ted went down the line, signing all of their stuff for an hour.

He was especially nice to the older Hall of Famers. He began serving on Veterans’ Committees, lending his extraordinary eyes, booming voice and considerable presence. In 1989, he talked about his change of heart.

“I have to tell you: I enjoy it more and more every year,” Williams told Sports Illustrated. “If a Hall of Famer is going through a depression period, well, there’s no better cure than going up there, where everybody makes you feel like a million dollars. The fun part to me is reminiscing with the older players. Talking with Joe Sewell about the year he struck out three times in 100-something games — he was still mad at Pat Caraway of the White Sox, who struck him out twice in one game. Or listening to Ralph Kiner talk about how much Hank Greenberg helped him when they played together in Pittsburgh… Bob Lemon is always riding me because I couldn’t hit him, and I tell him that instead of giving me that junk he threw up there, he should have pitched me like a man.”

Here it is, 2024, 22 years after his passing, and Hall of Famers are still talking about him.

“It was Spring Training of 1969,” Johnny Bench recalled. “We were in Winter Haven, and I was starting my second full year with the Reds. I asked Roy Sievers, who was one of our minor league managers and knew Ted, if he could go over and ask him to sign a ball for me. When he came back with it, I saw that he had written, ‘To Johnny Bench, a Hall of Famer, for sure.’ You can imagine how I felt, having a war hero, the last .400 hitter, John Wayne with baseball cleats, a world-class fisherman, giving me his seal of approval that early in my career.”

Dennis Eckersley came over to the Red Sox from the Indians in the spring of ’78, and, “I can still hear his booming voice talking with [Carl Yastrzemski] behind the cage. I even had dinner with him and a bunch of guys that spring, but I was so scared of him that I didn’t say much.”

All of them remember well the 1999 All-Star Game in Boston, when Williams came onto the field in a golf cart, doffing his cap to the cheers of the packed crowd before being surrounded by players from both All-Star teams and the All-Century Team. Who can forget him gingerly standing up and then passing the torch by throwing a strike to Carlton Fisk, who would be inducted into the Hall the next year.

You would need a giant baseball to contain the signatures of all the members of the Baseball Hall of Fame. But you just might want to save the Sweet Spot on such a ball for Ted Williams.

Steve Wulf is a freelance writer living in New York City