He covered it all

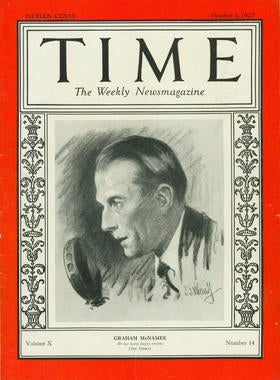

Time, then and now a weekly newsmagazine, was only in its fifth year of publication in October 1927. The covers often featured a single individual, who would then appear in an article in the magazine. Other notable cover subjects from 1927 included publisher William Randolph Hearst, future Baseball Hall of Famers John McGraw and Connie Mack (Time used his birth name: Cornelius McGillicuddy), Britain’s King George V and Queen Mary, and, in a separate cover, their sons, Princes Edward, Henry, and George, one of whom (Edward) would later ascend to – and abdicate from – the throne.

Baseball enjoyed great popularity nationwide during the 1927 season. The Yankees’ Murderers Row – featuring American League MVP Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth’s record 60 home runs – propelled the team to 110 wins, coasting to the pennant with a 19-game lead over the second-place Athletics. They then swept the Pittsburgh Pirates – who had survived a tight pennant race with the Cardinals and Giants – in the World Series.

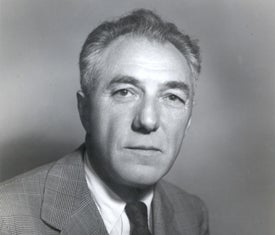

Detailing the 1927 World Series for fans with radios was McNamee, who had called them all since 1923 on the relatively new telecommunications format. Commercial radio, like baseball, surged in popularity as the two came of age together after World War I. Baseball games were made for radio, and McNamee, a concert singer-turned-broadcaster, detailed the action for millions of Americans.

“‘Good evening, Ladies & Gentlemen of the radio audience’ has become almost a trademarked phrase to the listening world. It means Graham McNamee,” the article states. “Things happen fast in the U.S., and, wherever in the U.S. anything nationally important is happening, Graham McNamee sits there telling the world.”

Tell the world, he did.

In addition to scores of baseball games, McNamee announced a variety of other sports, including boxing matches, and other major events such as Charles Lindbergh’s arrival in New York following his transatlantic flight, political conventions and presidential inaugurations. The Time article describes his call of the infamous and controversial “Long Count Fight” between world heavyweight champion Gene Tunney and former champion Jack Dempsey, held on Sept. 25, 1927, in Chicago.

While the article notes when various listeners died of excitement during the fight – presumably as a result of McNamee’s account – it also notes that McNamee himself was not fully aware of the technicalities of the long count, probably due to his still-growing knowledge of the sports he was announcing. The long count resulted in Tunney’s retaining of the championship.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“Announcer Graham McNamee could scarcely be expected to grasp immediately the technical detail here involved, through which Dempsey protested to the Illinois Boxing Commission that he had won the fight,” the article claims.

Criticism of McNamee was not uncommon, as he was doing what few, if any, had done before him. Radio was in its nascent stages, as was sports broadcasting, making McNamee a true pioneer in the field.

“From the relatively simple process of announcing bedroom storytellers and weather reports on the regular studio program, Announcer McNamee has assumed a position of national prominence,” the article reads. “Inevitably, he has had much criticism. Sports experts grumble that he does not know the sport he is describing. Radio executives answer that neither do the listeners; that colorful, general reports are more satisfying to the mass than accurate technical descriptions.”

Though Carlin teamed with McNamee to broadcast some World Series games, fights, and football games, he became manager of WEAF and later a vice president for NBC and the Mutual Broadcasting Corporation.

McNamee would remain behind the mike up until his death in 1942.

McNamee, not Carlin, secured the cover of Time and, almost 90 years later, he would join select baseball broadcasting company by winning the Frick Award.

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum