- Home

- Our Stories

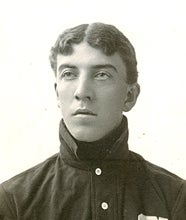

- Lee Richmond created baseball perfection

Lee Richmond created baseball perfection

The Paul Dickson Baseball Dictionary defines a perfect game as “a no-hitter in which all 27 opposing batters fail to reach first base, either by a base hit, base on balls, hit batter, fielding error, or by any other means.”

The entry also stipulates that the first use of the term ‘perfect game’ occurred on Jan. 10, 1909 when the Washington Post reported that “[Ed] Walsh congratulated Addie Joss on the latter’s feat of pitching a perfect game [on October 2, 1908].”

Through the 2025 season, there have been 24 official perfect games in AL/NL history. But few realize that southpaw Lee Richmond pitched the first such game for the National League’s Worcester Ruby Legs.

The Cleveland Blues were Richmond’s opponent on June 12, 1880 when baseball history was made. But, if the term ‘perfect game’ was not used until 1909, what did they call this game?

Richmond himself actually provided the best description of the event when he was quoted as saying: “It is a singular thing of that no-hit, no-run, no-man-reach-first game in 1880 that I can remember almost nothing except that my jump ball and my half stride ball were working splendidly and that the boys behind me gave me perfect support.”

The local paper, the Worcester Evening Gazette, provided coverage for the day and described this game as “a wonderful shut out” and “the best baseball game on record.” The Gazette also reported, “…so faultless a game was rapidly played. It was half over in 45 minutes.” Even with a brief rain delay of seven minutes in the eighth inning, “the total time of one-hour and 26 minutes [made] the game was one of the quickest ever played.”

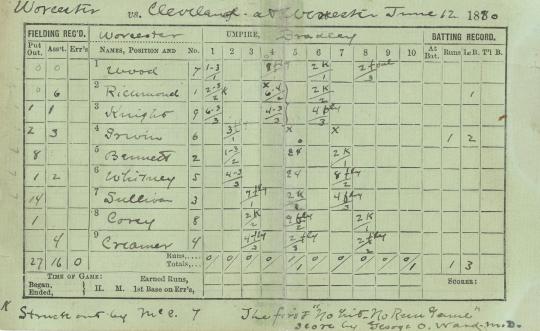

Details of the game, as can be seen by reviewing the original scorecard which is held within the archives of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, also show that Richmond, like so many other perfect game pitchers, was saved by a defensive gem. This particular play occurred in the fifth inning when Cleveland’s clean-up batter hit a line shot to right field for an apparent single. However, the right fielder and team captain, Lon Knight, charged in and threw the ball to first base to get the runner out at first base. Had he gone to second, as would be the standard play, Richmond would have lost the no-hitter and his place in history.

It should also be noted that Cleveland’s pitcher, Big Jim McCormick, who would notch 45 victories that season, was also throwing a very good game. He allowed just three hits and only one run, that coming on a double error by second baseman Fred “Sure-Shot” Dunlap. Richmond was later quoted as saying: “I used to think Dunlap was the greatest second baseman in the world.”

While perfect games are a venerated element of baseball, the first man to accomplish this feat is often forgotten.

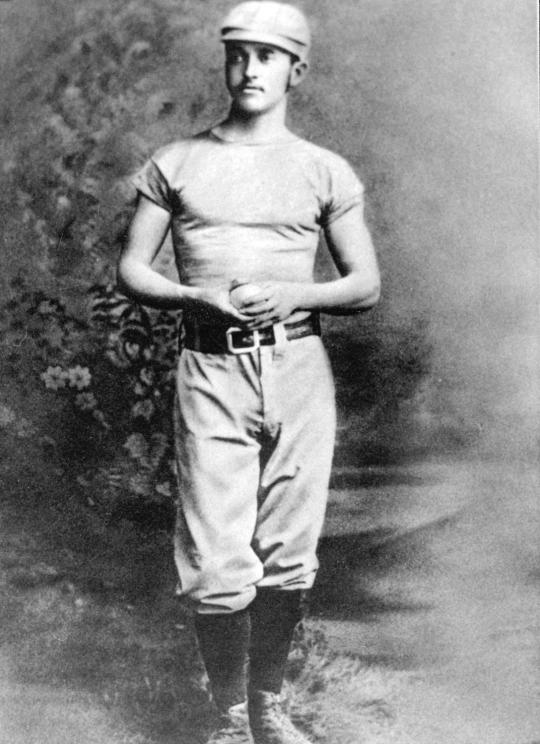

Richmond was born on May 5, 1857 in Sheffield, Ohio, the son of a Baptist minister and the youngest of nine children. He attended Oberlin Preparatory College near Cleveland, and was a student at Brown University in Providence, R.I., when he signed a contract to pitch for the Worcester squad. He needed the money to help pay his college bills, and his reported salary of $2,400 would have made him a franchise player in those days. He went 32-32 in 1880, while starting in 66 of the teams 83 games, and appearing in eight additional games.

Richmond also pitched for the Brown University baseball team and was active in a number of student activities. To a certain degree, these played a part in the story of his perfect game.

On the Thursday prior to his Saturday perfect game, Richmond had shut down Cleveland 5-0 in a game played in Worcester. He then returned to the Brown University campus to attend what is described as “graduation festivities and parties,” all of which kept him going until 4:30 a.m. when he stepped in to play in a class baseball game. He finally went to bed at 6:30 a.m. and slept until about 11:30 a.m., when he woke up to catch the train to Worcester. The train was delayed, so he was forced to pitch without having the chance to eat a meal or even to warm up properly.

And, with this background, he pitched his perfect game.

One other historic note should be made, as Richmond is often given credit for being the catalyst for the development of rules which prohibit professionals from playing in college sports. This restriction can be traced forward to today’s NCAA regulations regarding this same topic.

His professional career did not last long, as he pitched for only a few more years. He went on to earn his medical degree from the University of the City of New York in 1883, making him one of the earliest ballplayer/doctors, and he practiced as a physician for several years. He returned to his native Ohio where he taught and coached at the high school and college levels for another 30 years. His teaching repertoire was extensive and included Latin, physiology and mathematics. He would eventually rise to serve as the Dean of Men at the University of Toledo.

While no longer active in the professional game, he remained an active fan of the Toledo Mud Hens and he is reported to have become an excellent golfer. He passed away on Sept. 30, 1929.

Several obituaries made making note of the rare event he introduced to baseball. However, many remembered him for other reasons, as noted by a published eulogy which said, “Honored as a gentleman, envied as a scholar, revered as a friend, respected as a man, Dr. Richmond will always be remembered by us who were proud to know him as a leader.”

Jim Gates is the librarian emeritus at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum