- Home

- Our Stories

- Lena Blackburne rubbing mud a secret of the game

Lena Blackburne rubbing mud a secret of the game

The existence of Bigfoot, the formula for Coca-Cola and the whereabouts of D.B. Cooper are longstanding mysteries in the American consciousness, but what about the National Pastime?

Turns out, baseball has its own unsolvable puzzle: The source location of baseball’s “magic mud.”

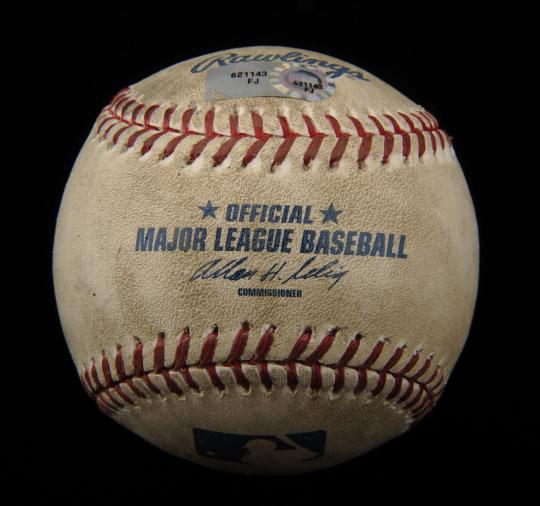

Today, Rule 4.01(c), under “Game Preliminaries – Umpire Duties” in the Official Major League Baseball Rules, reads, in part: “The umpire shall inspect the baseballs and ensure they are regulation baseballs and that they are properly rubbed so that the gloss is removed.”

But what specifically is being “properly rubbed” on all MLB baseballs?

Simply put, it’s dirt and water – and cannot be produced without the help of Mother Nature.

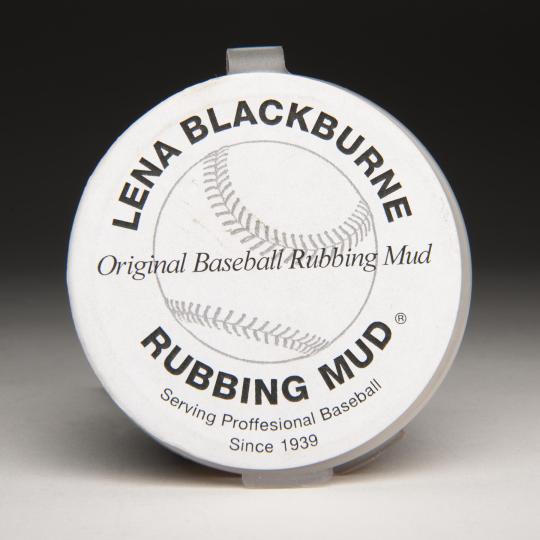

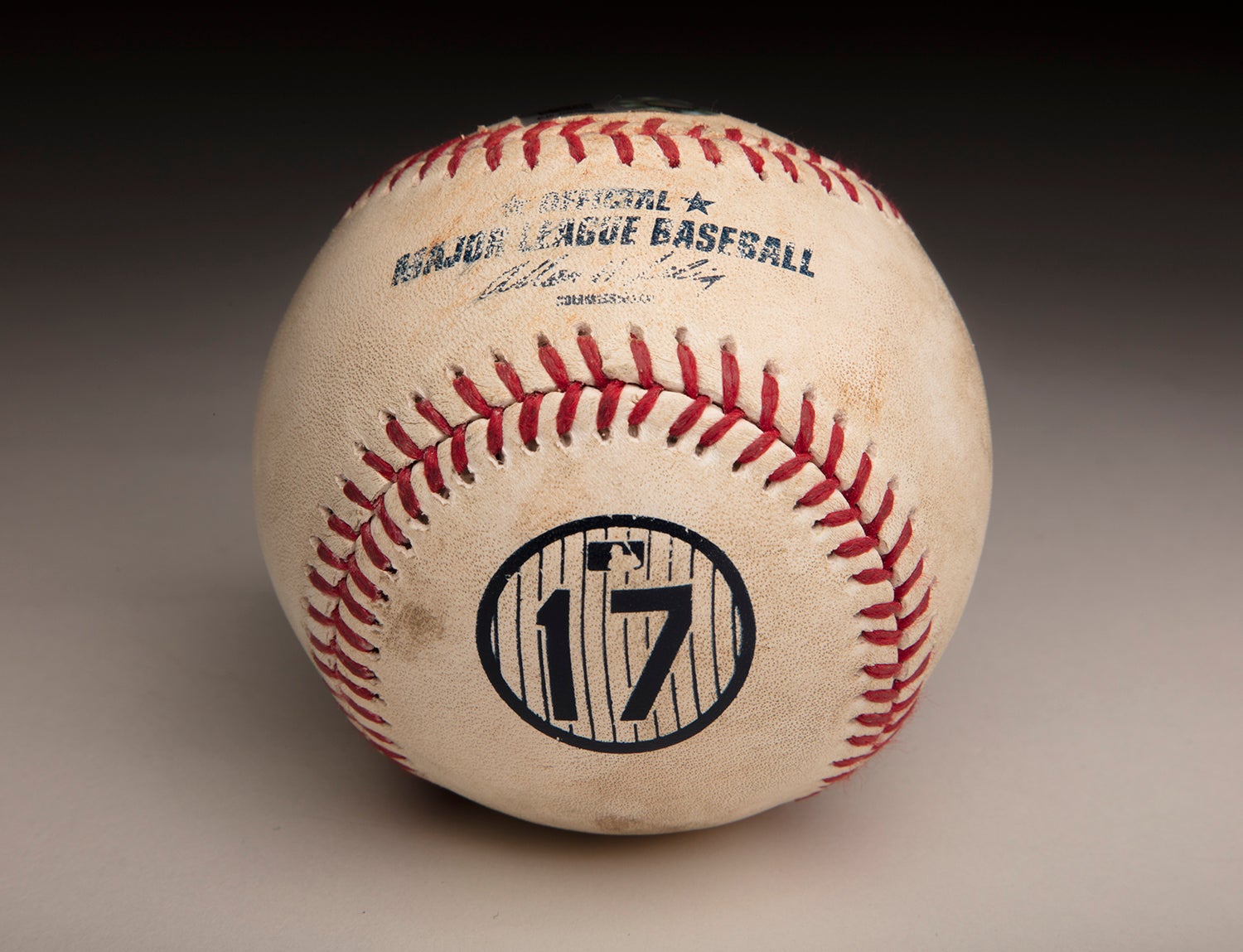

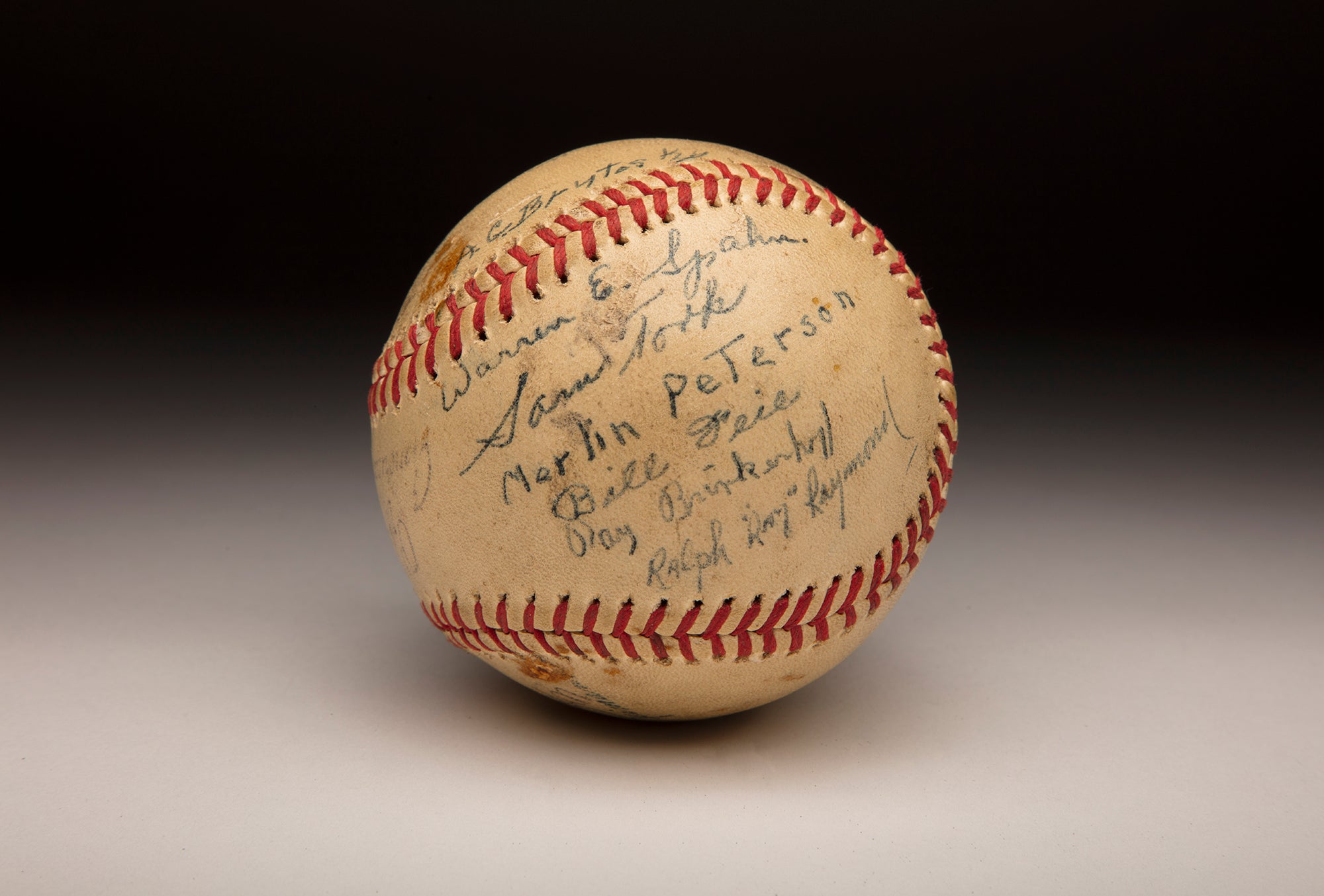

Lena Blackburne Baseball Rubbing Mud has been used in the majors dating back to the 1930s to improve the grip and dull the shine of new baseballs. Before every game, dozens of baseballs are rubbed with this one-of-a-kind specialty product, derived from a secret source, by an umpire or other club personnel. No other foreign substance can be applied to new baseballs before they are used.

Since Cleveland’s Ray Chapman died in 1920 as the result of being hit in the head with a pitched ball, the game had made efforts to improve the welfare of its players as it relates to the baseball. Pitchers can’t get a good grip on new, shiny baseballs – and hitters are sometimes blinded when the sun or indoor lighting hits the too-white surface.

In July 1929, National League President John Heydler issued an edict to his umpires to treat new baseballs with dirt as a means of aiding the pitchers, claiming that slightly soiling the orb will make it easier for pitchers to handle and at the same time lessen the luster and brightness of the cover.

“We can put a man on the moon, but we can’t manufacture a baseball that doesn’t have a slick hide and a white gloss to it,” said Durwood Merrill, an American League umpire from 1977 to 1999. “So in the old days, they’d just rub ‘em with dirt from around home plate, with maybe a spit or two of tobacco juice.”

Here’s the dirt on baseball rubbing mud: One can trace its history and its secret location back to the 1938 season, when American League umpire Harry Geisel complained during a game about the job of taking the slickness off new baseballs. In those days, ballpark dirt and water were the main raw ingredients, as well as the occasional tobacco juice and shoe polish, used on new baseballs.

But the ballpark-made mud was often too coarse, thus putting marks on the cover of the baseball, which would allow pitchers to get their fingernails in those marks and make the ball travel in an unnatural path.

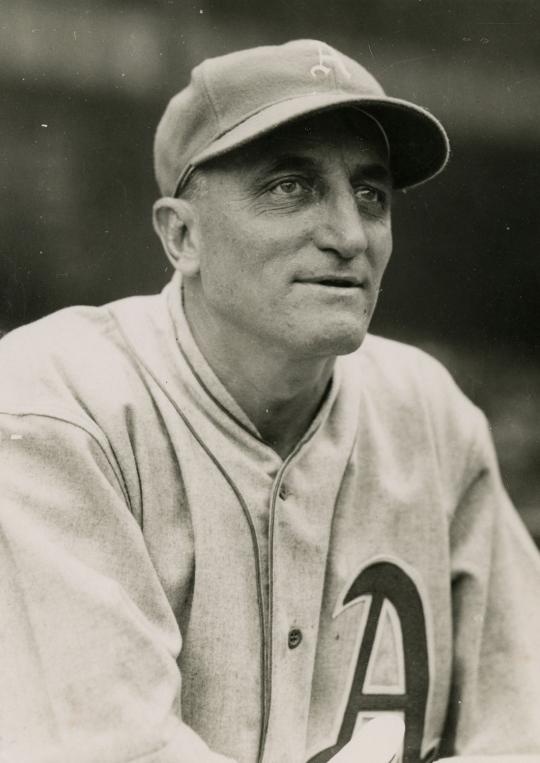

Lena Blackburne, an eight-year veteran of the big leagues who was at the time a third base coach with the Philadelphia Athletics, overheard Geisel’s griping and his thoughts raced back to his youth. As a child, Blackburne had discovered a special mud while wading in Pennsauken Creek, a branch of the Delaware River, near his southern New Jersey home.

“I noticed in those days that the outgoing tides purified the mud at the bottom of the creek, leaving it inky black and sticky,” Blackburne remembered. “Two streams come together where I get my mud. That means it is filtered twice and is very fine.

“I was a kid pitcher in those days and I often used the mud on a new ball – when we were lucky enough to get one.”

After experimenting with the Burlington County mud he remembered from his childhood, and adding a secret ingredient, he later gave a can of it to Geisel to de-gloss the new baseballs. Soon afterward, as the story goes, every American League team was getting a supply of the odorless, greaseless, and as smooth as pudding mud from Blackburne at a very reasonable price. Being a longtime Junior Circuit man, Blackburne resisted selling his mud to the National League until the mid-1950s.

Blackburne’s big league career record as a good-field, no-hit infielder featured 550 games with four different teams, mainly the White Sox, a team he also managed for two seasons. But he may be most remembered for what he did off the field when he developed a business dredging mud from the bottom of a Delaware River tributary.

Having been in professional baseball dating back to 1908, either as a player, coach, scout or manager, Blackburne often marveled at his new role in the game being in the mud supply business.

“This isn’t a business; it’s a hobby,” Blackburne said. “Besides, what I get I share with my wife. She called it her ‘mud money.’

“I’ve stuck in baseball,” he added, “because I got stuck in the mud.”

When he passed away in 1968 at the age of 81, with the knowledge that every baseball put into play from March to October is rubbed down with Lena Blackburne Baseball Rubbing Mud, the first paragraph of his New York Times obituary referenced his late-in-life role in the game: “… originated the idea of rubbing mud on new baseballs to remove their slippery finish …”

After taking loads of the New Jersey mud home, usually between fall and spring, Blackburne would filter it, then add a special something that would make it non-staining and smooth as cold cream. The concoction seemed to contain a superfine grit that could scuff a baseball’s cover evenly with the mud nearly invisibly.

Bill Kinnamon, an American League umpire during the 1960s, once said: “There’s something about this mud. I don’t know how to explain it. It takes the shine off without getting the ball excessively dark.”

According to Blackburne, working the mud through a sieve “takes out any stones. They would wreck a ball. Of course, umps never let any of this mud get into the stitches of a ball. The balance would be ruined, and pitchers would make the ball perform the aerobatics of a horsefly under a lampshade.”

After Blackburne passed away, his mud business, along with all its secrets, was willed to childhood friend John Haas, who had helped out with Blackburne’s affairs.

“Mr. Blackburne made me promise that I would never give away to outsiders the secret of the source of the mud,” Haas said. “He also made me promise that, since he had no children of his own, I would see to it that the business was handed down through the family.”

In relatively short order, Haas passed it down to his son-in-law, Burns Bintliff.

“He (Haas) picked me because I was his son-on-law and also because he knew I’d played semipro baseball as a young man on the Burlington County team and had remained a committed baseball bug,” said Burns Bintliff. “It’s better than tobacco juice and far superior to everyday mud. Mud from the Delaware River tributary contains an ultra-fine abrasive that strips off the factory gloss but doesn’t damage the cover, and it doesn’t discolor the ball.”

Burns Bintliff would later admit the source of the baseball’s dirtiest secret was somewhere in the south of New Jersey.

“Everybody has their own idea where it comes from. Everybody thinks it’s the Delaware River, but it isn’t,” he said. “I’ll tell you this: Where it comes from is covered at high tide and uncovered at low tide. Other than that, it’s none of your business. That’s my standard response.”

In 1982, a scientific analysis of the rubbing mud conducted at The New York Times’ request found that more than 90 percent of it was finely ground quartz, probably crushed by ice that covered New Jersey during the Pleistocene Epoch more than 10,000 years ago.

“The surprise is that there is very little clay in it, so it would be terrible for a potter to use,” said Dr. Kenneth S. Deffeyes, professor of geology at Princeton University. “The overwhelming mineral in there is quartz, just like sand only finer. It is more than 90 percent quartz in a range of sizes with sharp edges.”

Burns Bintliff would ship his topnotch mud in coffee cans his friends and neighbors would leave on his porch. A one-pound coffee can could hold three pounds of mud and last a whole season.

“I don’t make much money from this,” Burns Bintliff said. “But my raw material costs me nothing and the supply will last forever.

“I wish I could raise my prices in proportion to what the ballplayers get in salaries. But the traffic wouldn’t bear it. I’m in this for the thrill,” he added. “I watch baseball on TV. Can you imagine how I feel knowing I’ve had something to do with every pitch at every single ballpark?”

What money the Bintliff’s did receive from their mud business went toward an annual getaway.

“It gives us enough to pay for the family vacation every year – and it’s always the same vacation,” said Burns Bintliff. “My wife, Betty, who’s the executive vice president and accountant of the business – she handles all the paperwork – and I go up to Cooperstown, New York, home of the Baseball Hall of Fame.”

A can of Lena Blackburne Baseball Rubbing Mud was donated to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1968 and was part of the Museum’s Evolution of Equipment exhibit for many years.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum