#Popups: Baseball’s greatest hit is ‘Take Me Out to the Ballgame’

Baseball and pop culture have intersected in America for more than a century. The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum takes a look at these cross-over stars and events in our web feature #Popups.

Today the song has permeated baseball and American culture (as well as several other nations) at an incredible level. Across the nation and world, the 7th Inning Stretch is rung in by playing of the iconic song. While each stadium and team may have their own traditions regarding how the song is sung, or if the line “home team” is replaced with the team name, “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” is a song that can (for a minute) unite fans of even the largest rivals.

“Take Me Out to the Ball Game” has even made a cultural impact in Japan. In addition to ballparks, it is not uncommon to hear the tune playing over the speakers in public transportation or in elevators.

The song has been featured in countless television and radio broadcasts. However, most notably the song was played continuously on WJMP of Kent, Ohio, during the 1994 Major League Baseball strike. The all-sports station used the song to protest the strike which left us without a 1994 World Series.

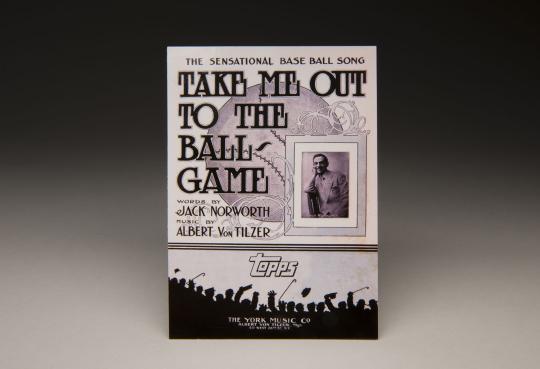

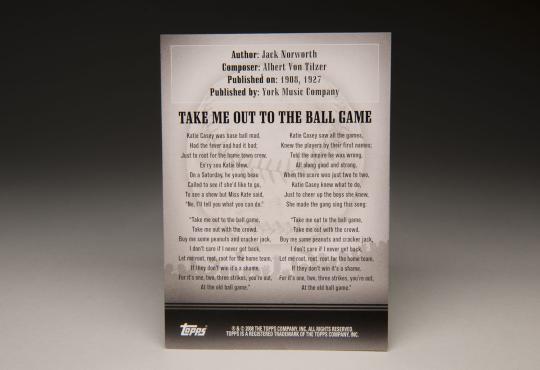

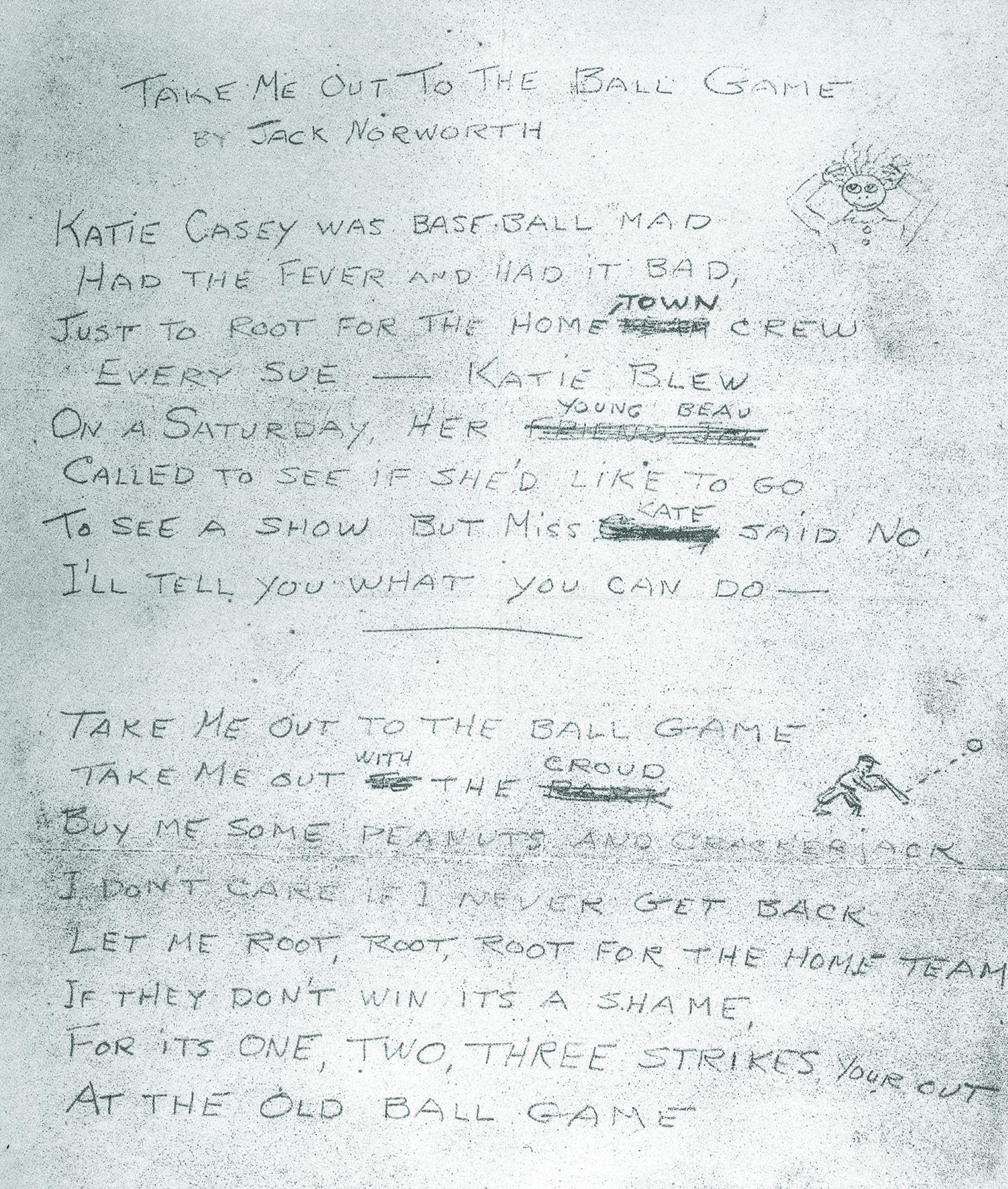

While most people know the chorus to the song, the verses and the history of the song are much less known. The song consists of two verses and two choruses. It was written by Jack Norworth and composed by Albert Von Tilzer. The two were music creators from iconic Tin Pan Alley. Interestingly, neither man had ever attended a baseball game at the time of the writing of the song.

The song follows a young lady by the name of Katie Casey. Katie is asked by her “young beau” if she would like to go a show, to which Katie replies “no, I’ll tell you what you can do” then the famous chorus breaks. Katie’s bravado would be endured today as verse two teaches us that knows all the players by first name, she heckled the umpire “good and strong” all game long.

However, Lyricist Jack Norworth rewrote the verses to the song in 1927. In this version a woman by the name of Nelly Kelly is asked by her boyfriend if she would like to go to Coney Island (in Brooklyn) to this, Nelly began to “fret and pout. And to him I heard her shout” at this point the classic chorus cuts in.

It is interesting that both versions focus on young ladies who wish to attend baseball games while their male suitors desire to go elsewhere. Usually baseball songs tend to focus on the men or boys who play the game, not the ladies in the stands. The reason for this, however may be explained by one simple fact: Jack Norworth had never attended a baseball game at the time he wrote either version of the song.

In fact, both men responsible for Take Me Out to the Ballgame did not attend a baseball game until decades after their famous song was penned. Vin Tilzer attended his first baseball game in 1928 and Norworth attended his first game in 1940.

The old adage, “Write about what you know” must have struck true with Norworth. The prolific lyricist wrote many well-known songs about courtship and only a few about baseball. Thus, it makes sense that the song’s protagonist would be a fan and a young woman.

It is often wondered who was the first to sing the song at major league ballparks. As this is now the standard norm, one would think it would be well documented, but it isn’t. From my research, the song was performed during Game 4 of the 1934 World Series. While this may not have been the first time the song was performed in an MLB game, it certainly wasn’t the last.

One thing is for sure, the Cubs do “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” differently than any other team. This is, oddly, in thanks to (then White Sox owner) Bill Veeck and Harry Caray. According to White Sox accounts, while Caray was an announcer for the team, he would often sing “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” in the booth, for his own amusement. One day, Veeck placed a mic in the booth for the sole purpose of letting fans hear Caray. The unsuspecting Caray was shocked to hear his own voice over the stadium PA speakers. Veeck reportedly stated that if fans heard Caray’s (notoriously bad) singing, they too would join in. When Caray made the jump across town to work with the Cubs, the tradition followed.

Nate Tweedie is the manager of on-site learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum