- Home

- Our Stories

- Four decades later, free agency still fuels baseball

Four decades later, free agency still fuels baseball

Free agency has become one of baseball’s foregone conclusions, a rite of winter, if you will. We take it for granted that it will become a major theme at the Winter Meetings, scheduled this year for Dec. 4-8 in National Harbor, Md. In fact, free agency has been around so long that it might be hard to remember a time in baseball’s rich history when players did not have the right to shop their services to the highest bidder.

Like much of baseball’s current financial structure, free agency finds its roots in the tumultuous 1970s. More specifically, the time of free agency’s birth was 1976, the year of the Bicentennial and the year that the Cincinnati Reds won a second straight world championship.

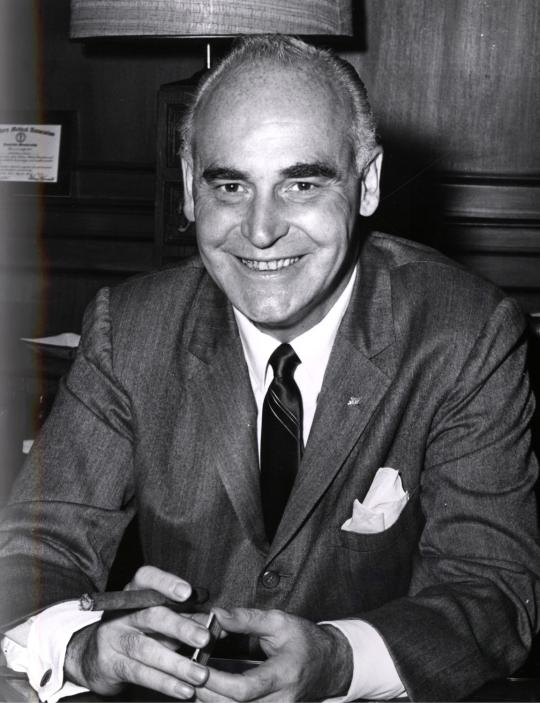

If you’re old enough to have remembered wearing bell bottom jeans or full color polyester pants, you might remember the dawn of free agency. It came about because of a landmark 1975 ruling by the late Peter Seitz, an independent arbitrator who – as part of a three-person board with one representative from the owners and one from the players – determined that veteran pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally should become free agents after playing a full season without signed contracts. When Seitz ruled in favor of the two pitchers, the MLB owners panicked. They worried that most players would become free agents on an annual basis, creating chaos. Not wanting that to happen, the owners negotiated a compromise system that allowed players to become free under two conditions: a) their contracts had expired and b) they had accumulated at least six years of major league service time.

It was an adept piece of negotiation by Marvin Miller, the head of the Players’ Association. He felt that all-out free agency might be bad for the players; if all players became free agents every year, then they would create an oversaturation of the market and actually compress salaries for all but the superstar players. By introducing a system of six-year free agency, Miller ensured that only a few players would become free each winter. Miller figured that demand would increase for those players, thereby pushing their salaries higher and higher. Miller figured right.

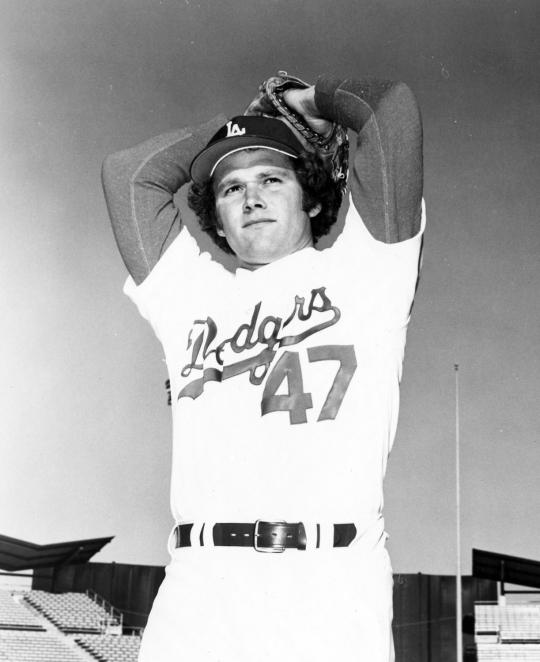

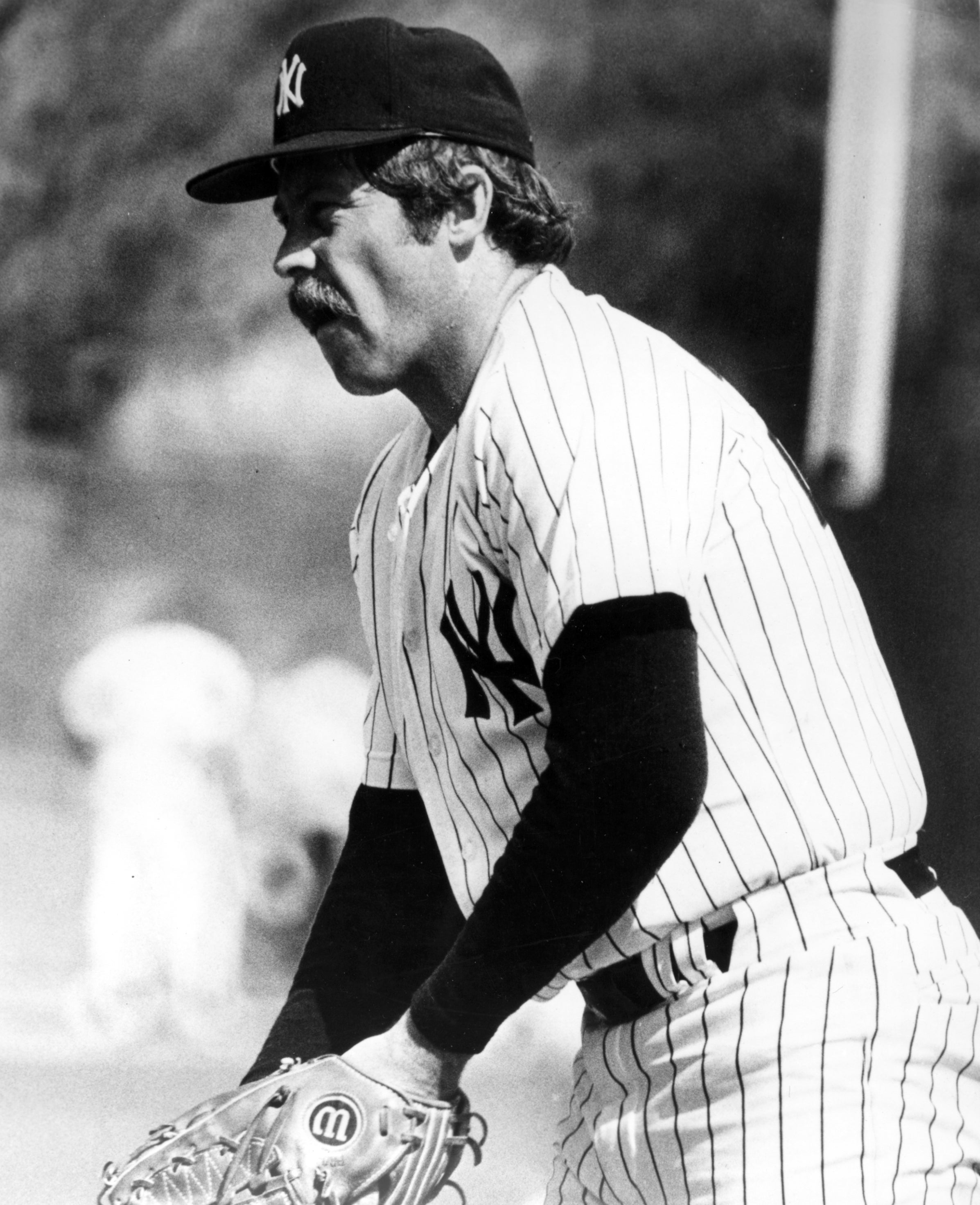

In 1975, Peter Seitz, an independent arbitrator, determined that Andy Messersmith (pictured above) and Dave McNally should become free agents after playing a full season without signed contracts, thereby changing the landscape of baseball negotiations forever. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

The free agent system that Miller and the owners agreed to is not the same as the system in place today. In 1976, free agency was tied to a re-entry draft. (The 24 established teams took part in the draft, but the expansion teams in Seattle and Toronto were excluded from making selections.) In order for teams to have the right to bid for a player, they first had to draft bargaining rights. A player could only be drafted by a maximum of 12 clubs. If a player was drafted by three or more teams, only those teams could negotiate with him. If the player was drafted by two teams or fewer, then he would be free to talk contract with any of the ballclubs.

In retrospect, the first free agent class looks like a who’s who of 1970s baseball talent. Hall of Famers Reggie Jackson and Rollie Fingers headlined the long list of quality players, which included standouts at almost every position: second base (Bobby Grich and Dave Cash), shortstop (Bert Campaneris), third base (Sal Bando and Richie Hebner), the outfield (Jackson, Gary Matthews, Joe Rudi and Don Baylor) and on the mound (Fingers, Doyle Alexander, Wayne Garland, Don Gullett, and Bill Campbell). All were regarded as top-tier talents at the time, the kinds of players who were expected to have an immediate impact on the pennant races in 1977.

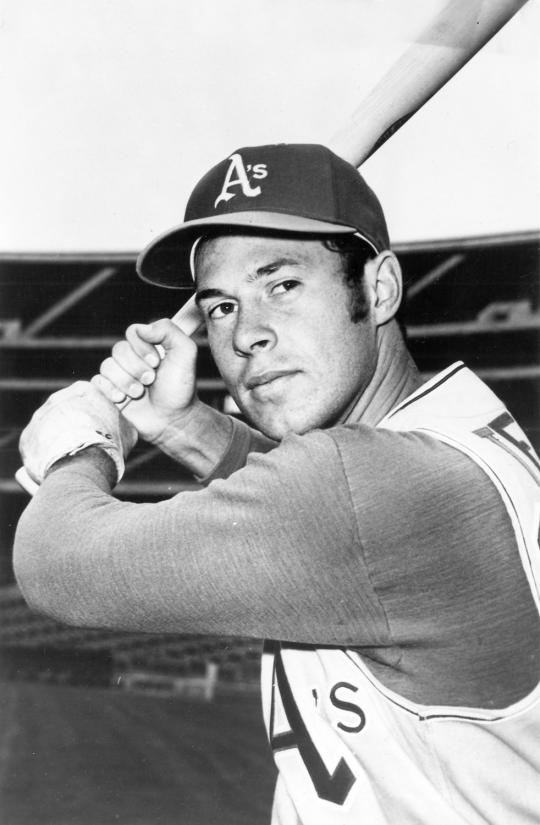

Yet none of these player proved to be the most sought after in the re-entry draft, which took place on Nov. 4 at New York City’s Plaza Hotel. That honor went to veteran catcher/first baseman Gene Tenace, who was the first player to be selected by a maximum of 12 teams. (By the end of the day, 12 other players would be taken by the maximum 12 teams.) A highly skilled offensive player who had played for all three of Oakland’s world championship teams in the early 1970s, Tenace was not a headline name like a Jackson or a Fingers. But talent evaluators understood his value because of his propensity to draw walks and hit home runs. Tenace would end up signing with the San Diego Padres, who also reeled in Fingers, making them one of the most aggressive teams when it came to spending free agent dollars.

One team chose not to take part in the re-entry draft at all. The world champion Reds, a fiscally conservative organization to begin with, did not draft a single player. They essentially thumbed their nose at the new system, expressing a desire to stress player development instead of becoming involved in bidding wars for high-priced talent.

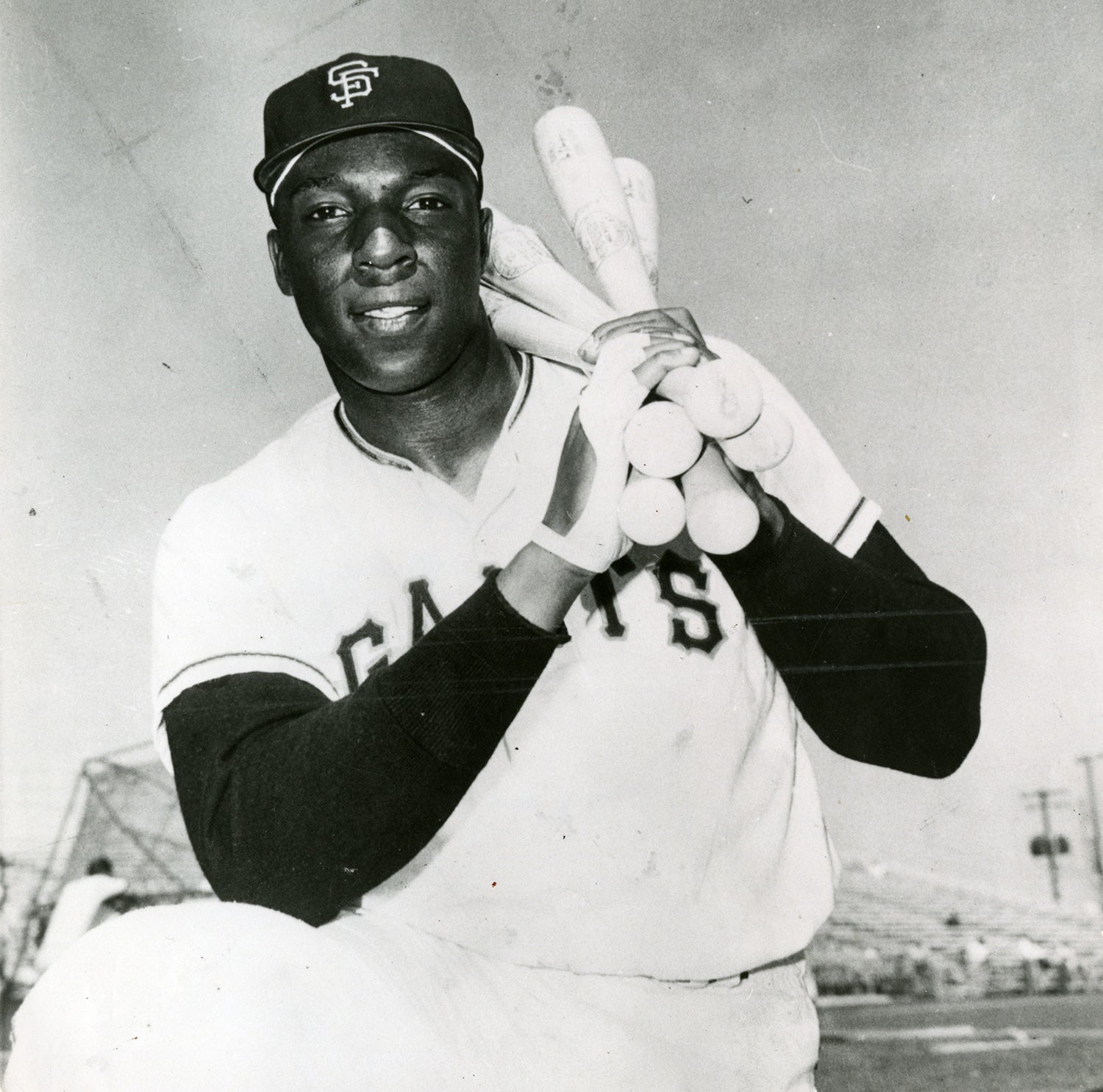

For some players, the re-entry draft became an exercise in futility. Several brand name sluggers, all of whom were on the downside of their careers, did not find a single taker in the draft. That group included Hall of Famer Willie McCovey and former All-Stars Dick Allen and Nate Colbert. Allen would sign a bargain basement deal with the A’s, but would retire by the middle of the 1977 season. Colbert, plagued by chronic back problems, found no interest from any team and opted for retirement. McCovey left Oakland and returned to San Francisco, where he resuscitated his career, winning Comeback Player of the Year honors in 1977.

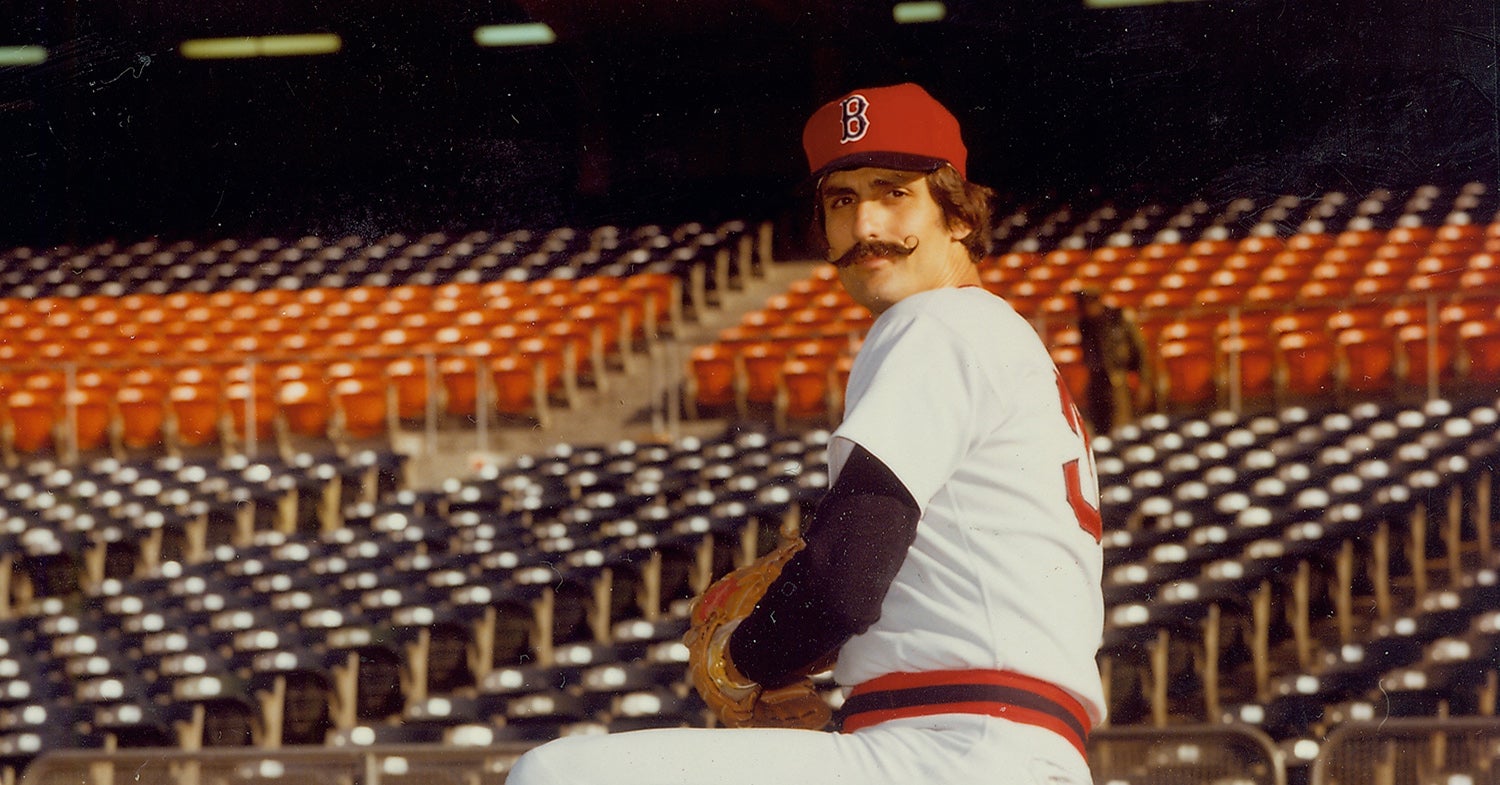

Unlike today’s free agency, where teams tend to wait weeks or even months before committing to signing players, free agents signed quickly in the winter of 1976. Only two days after the re-entry draft, Campbell signed a four-year contract worth a total of $1 million with the Boston Red Sox. Within three weeks of the draft, 11 free agents (all A-list performers) had signed new contracts.

As teams embarked on a spending frenzy, A’s owner Charlie Finley, who was losing eight of his players to free agency, observed the situation with contempt. “What the owners are doing is stupid,” Finley told the Sporting News. “They’re going to bankrupt themselves.” By 1980, Finley had seen enough. He sold the A’s, leaving the game entirely.

The first free agent class certainly had its share of busts. No bust was bigger than Baltimore Orioles ace Wayne Garland, a 20-game winner in 1976. Garland left the pitching-rich Orioles for the Cleveland Indians, accepting a 10-year contract worth a total of $2.5 million. When Garland told his mother about the money, she gave him a blunt assessment: “You’re not worth it.”

How right Mrs. Garland proved to be. After winning 13 games in 1977, Garland injured his arm and underwent rotator cuff surgery, a death knell for pitchers of that era. Garland was never the same; he would win only 15 more games over the last four seasons of an injury-wrecked career.

In terms of booms, a Hall of Famer provided the biggest return, while also making most of the headlines that winter. Reggie Jackson became the subject of a celebrated bidding war between the Montreal Expos and the New York Yankees. The Expos, who had made Jackson the first selection of the re-entry draft, offered him more money, but Jackson chose the spotlight of New York City, “settling” for a five-year deal worth $3 million. Jackson turned out to be worth the investment – and then some. Over his five seasons in the Bronx, Jackson helped the Yankees win three pennants and two World Series.

While the Yankees spent money wisely on Jackson, the Angels took an even more aggressive approach and reeled in three major free agents: Grich, Rudi and Baylor. Expected by some to win the American League West, the Angels flopped. They finished 74-88, a complete non-factor in the pennant race. The Angels would not reap dividends on their spending until 1979, when Baylor won the MVP and the Angels claimed the Western Division for the first time in franchise history.

The results produced by that that first group of free agents were certainly mixed, but the news generated by the first class in 1976 reverberated throughout the sport. Baseball’s hot stove league, with its rumors and whispers, took on a different dimension, changing the landscape of every winter since.

Forty years later, free agency still keeps the hot stove cooking under the fullest of fires.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame