- Home

- Our Stories

- Players after prison

Players after prison

While baseball has a long history of being played behind prison walls, from Civil War prison camps to present-day San Quentin, professional baseball has its own history with those players who made those prison leagues a possibility, both with their talent and their sentences.

Professional leagues have had to ask themselves how to approach the fact of players who are often put into a role model position by virtue of their status and visibility but who have also committed acts serious enough to result in their incarceration.

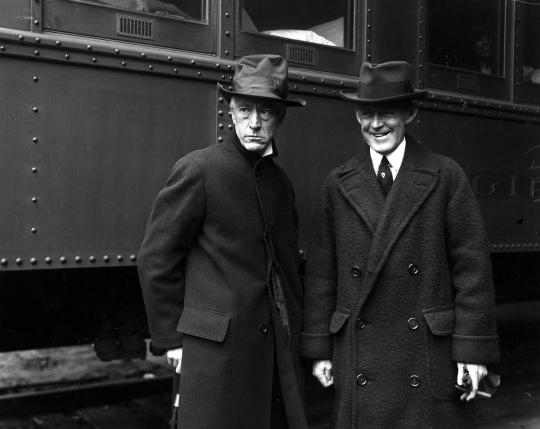

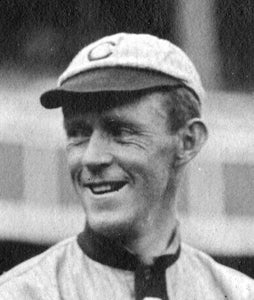

The question of how to deal with prison baseball players after their release is one that decision-makers in the game have been grappling with for quite some time. In 1935, Edwin C. “Alabama” Pitts was released from Sing Sing Prison in Ossining, N.Y., after serving six years of an 8-to-16-year sentence for robbery. Pitts had been a star in Sing Sing’s prison baseball program and decided to try to take those skills to the big leagues following his early release. In fact, Hall of Famer Johnny Evers, then the General Manager for the Albany Senators of the International League, and Albany team owner Joe Cambria were so impressed by Pitts that they offered him a contract for $200 a month.

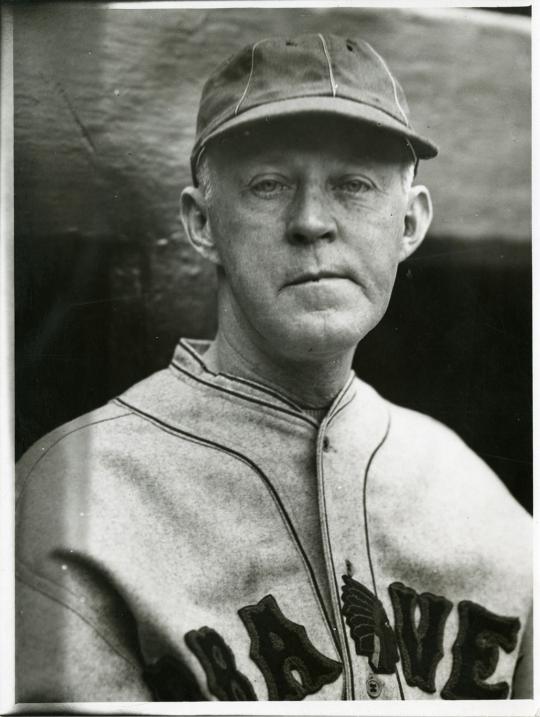

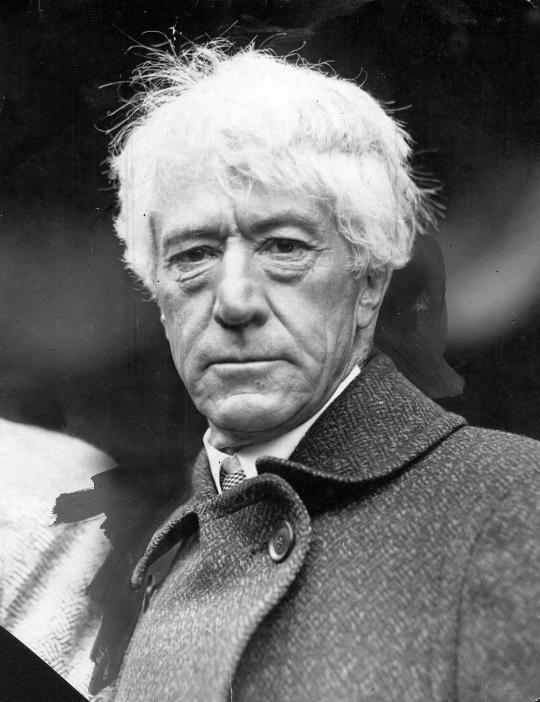

But talent and the desire to play the game weren’t enough for everyone to forget Pitts’ past. International League president Charles H. Knapp and National Association President Judge W.G. Bramham agreed that allowing an ex-convict into professional baseball was not in the game’s best interests. Knapp took it a step further, refusing to acknowledge Albany’s contract with Pitts. A minor league executive committee was convened to decide whether or not Pitts could play. They sided with Bramham, who decreed that “ex-convicts could not contract with a professional baseball team.” Evers was so incensed that he threatened to leave baseball forever if the decision was not overturned. He told the media in June that “I have been connected with baseball for thirty-three years...and I played the game squarely and by the rules. Baseball is a game of sentiment, a game that appeals to the heart. This decision tramples on sentiment and stabs fair play to the heart.”

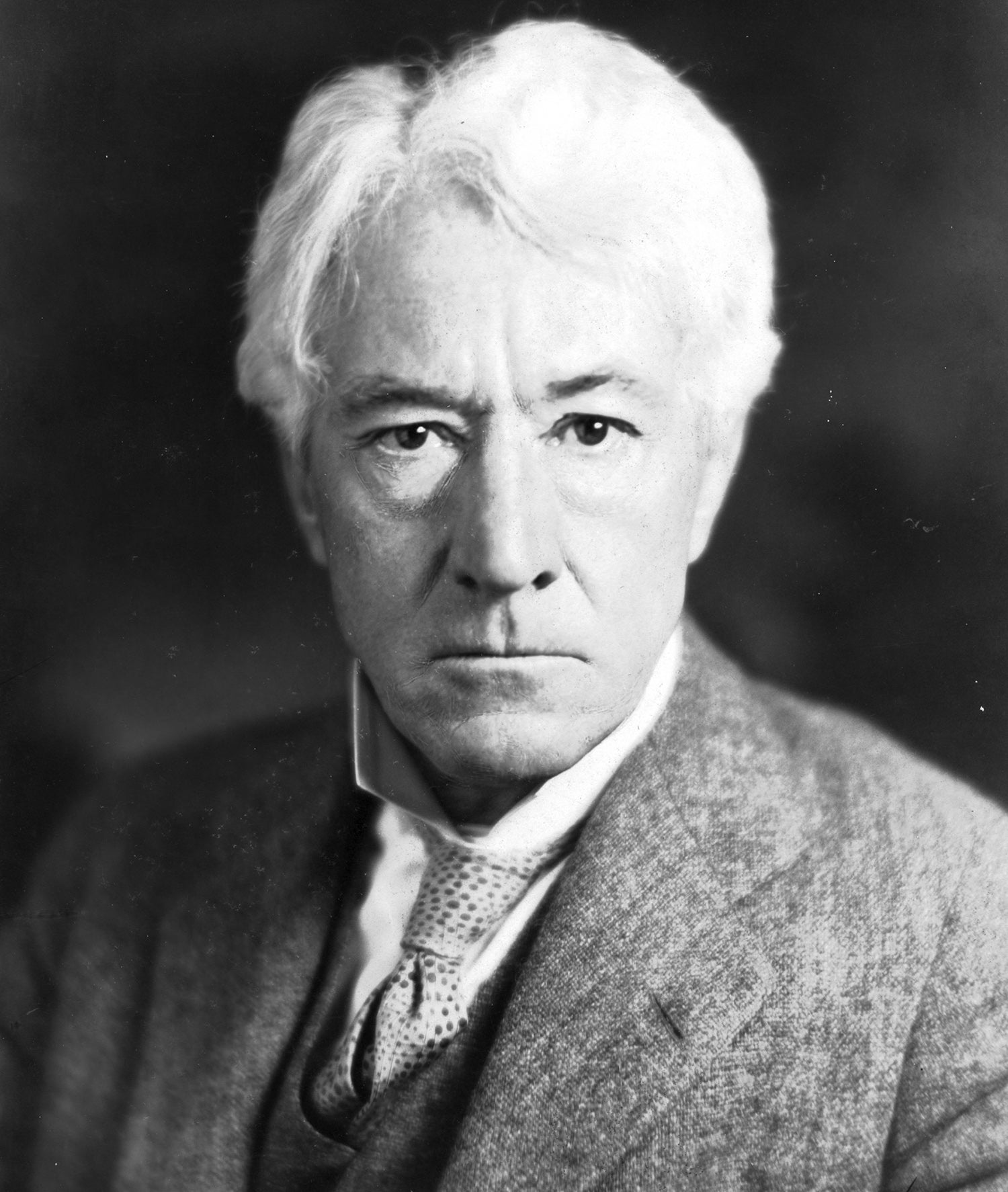

The case eventually made its way up to Major League Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis by way of Pitts’ appeals on his ban from professional baseball. On his appeal to be allowed into the game, Pitts said, “I hope this doesn’t sound like I’m bragging, but I sincerely believe I can play ball in this league. I’ve seen five of the eight clubs, and I really think that I can do as well as most of the outfielders I’ve watched. I know I can.”

After a week’s deliberation, Landis overturned the committee’s decision and announced that Pitts could play ball after all. According to The New York Times, Landis’s decision did not mean that baseball would “relax its character standards for players,” but rather “not stand in the way of Pitts in his attempt once more to attain an honorable position in society.” Pitts went on to play for the Albany Senators for the 1935 season and became something of a journeyman through minor league baseball for the next five years, and added a stint with the Philadelphia Eagles as a halfback in 1935. Pitts’ career and life were both tragically cut short in 1941, when he was killed in a bar fight.

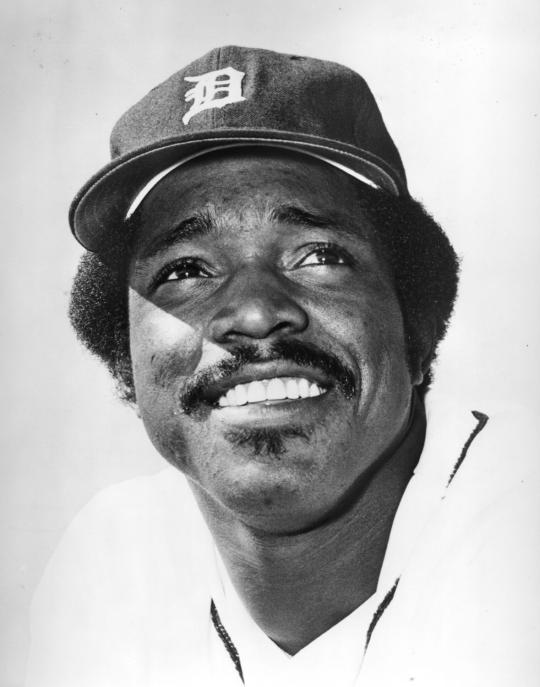

In 1970, 35 years after Pitts’ fight to be allowed into professional baseball, Detroit native Ron LeFlore entered State Prison of Southern Michigan on an armed robbery charge. He spent three years incarcerated, during which time he turned to baseball as a way to deal with his sentence. Amazingly, this was the first time in his life LeFlore played baseball. The Boston Globe reported that, in his three seasons as a member of the prison team, LeFlore hit for averages of .509, .469, and .569, respectively. A fellow inmate noticed his potential and, through a series of connections, got word to Billy Martin and professional baseball soon caught wind of this talented player who happened to be playing behind prison walls.

LeFlore signed a contract with the Detroit Tigers organization as soon as he was released in 1973, debuting in the majors in 1974. He went on to spend six seasons with the Tigers, one with the Montreal Expos, and two with the Chicago White Sox. In 1976, he batted .316, was elected to the All-Star Game, and put together a 30-game hit streak; in 1977, he improved on that batting average and hit .325. And in 1980 he led the National League with 97 stolen bases with the Expos.

He went on to compile a lifetime average of .288 in the big leagues. With statistics like these and a career that spanned nine years, LeFlore certainly stands out as the game’s most prominent example of a former prison baseball star turned professional.

Of course, baseball players can also become prison stars after a professional career. In 1948, after debuting in the major leagues with the St. Louis Browns, Ralph “Blackie” Schwamb was arrested for and convicted of murder in a robbery gone awry. He was sentenced to life in San Quentin prison in 1949, though he was paroled in 1960. Before that, the 22-year-old Schwamb had pitched in 12 games for the Browns, held a 1-1 record and had an ERA of 8.53.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

In 1950, however, Schwamb joined the San Quentin All-Stars, a recreational baseball program for the prison’s inmates. He became something of a sensation, and was certainly the most talented player anywhere in the prison’s program. As Eric Stone mentioned in his book on Schwamb, Wrong Side of the Wall: The Life of Blackie Schwamb, the Greatest Prison Baseball Player of All Time, “Blackie was achieving the success he’d always wanted. The problem was that it was far from the limelight.” When Schwamb was released at age 34, he tried to capitalize on that success by attempting a comeback in professional baseball. He pitched for the Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League after his parole, though he pitched in only six games and compiled a record of 1-2.

The opportunity to take part in the game of baseball can provide fulfillment and the chance to be part of something bigger than one’s self. While not the norm, those opportunities can transform the lives of inmates after their release and provide hope for a different kind of future.

Katherine Adriaanse was a library research intern in the Class of 2016 Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum