- Home

- Our Stories

- Sports cartoonists used baseball as primary messaging

Sports cartoonists used baseball as primary messaging

This is a story about dinosaurs.

Not the kind that roamed the earth 200 million years ago, but about sports cartoonists who proliferated the nation’s newspapers for the first three-quarters of the 20th century before becoming nearly extinct due to a similar drastically changed environment.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

“We all went the way of the newspapers,” laments Charlie McGill, who began his career May 20, 1954 with the Bergen Evening Record (now The Record) in Hackensack, N.J. “It began with the slow demise of the afternoon papers which were heavily comprised of features and thus the perfect niche for cartoons. But then with the rise of the internet and papers starting to go online, there was just no place for cartoons.”

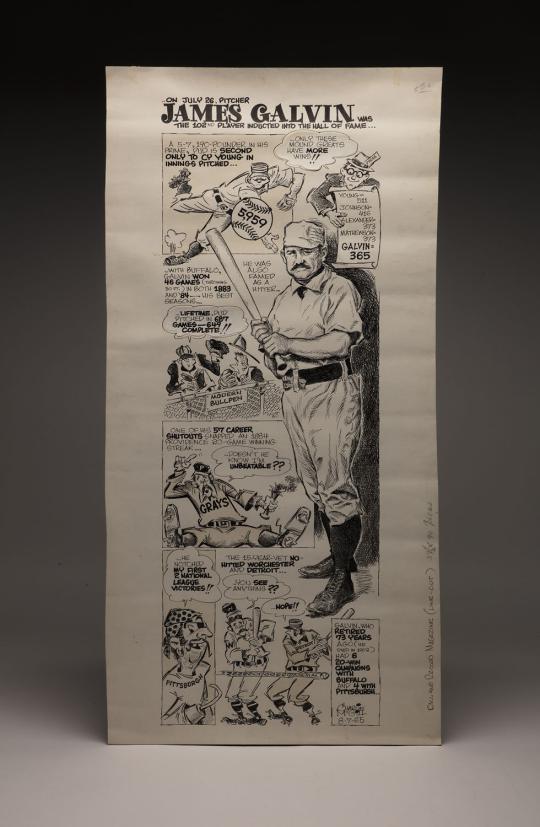

A favorite annual ritual for McGill was to draw a cartoon of the newest Hall of Famers that ran in The Record the Friday before

Inductions in Cooperstown. His last was Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford in 1974 – that’s when The Record’s editor told him to put away his pen – and his most challenging was Pud Galvin, the only inductee in 1965.

“I had never heard of Galvin, but after looking him up I saw where he was certainly deserving…over 360 wins,” McGill said. “So I went through my files and actually found a picture of him – full body shot – and did the cartoon. I wonder if that’s the only cartoon there ever was of Pud Galvin.”

If anything, sports cartoonists became victims of space. Sports editors simply did not see the value of devoting four-by-six inches of real estate in the sports pages to a cartoon, where a photo or more copy would suffice at no extra cost. Cartoonists became viewed as luxuries the papers could ill afford. And yet, in their 1940’s-to mid-‘60s heyday, cartoonists, both on the editorial pages and in the sports section, were among the most influential writers in the papers.

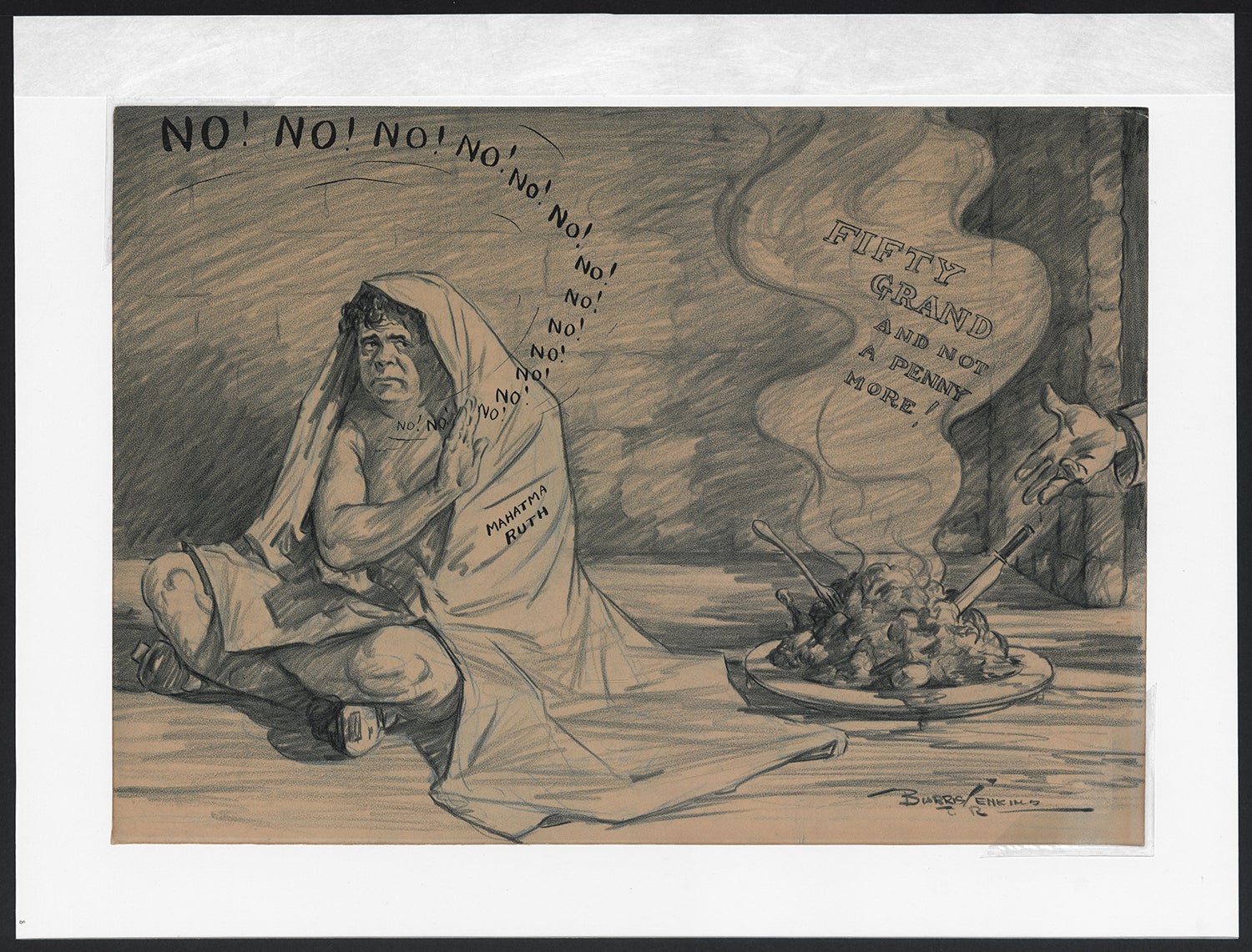

Cartoonist Charlie McGill annually would draw the newest members of the Hall of Fame for The Record in Hackensack, N.J., heading into Induction Weekend. This cartoon of Pud Galvin ran in 1965 and is now a part of the Hall of Fame collection. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

From the dean of cartoonists, Willard Mullin of the New York World-Telegram & Sun, to Burris Jenkins of the New York Journal-American, Gene Mack of the Boston Globe, Lou Darvis with the Cleveland Press, Amadee Wohlschlaeger with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, to Karl Hubenthal of the Los Angeles Examiner, nearly every major newspaper, especially the afternoon ones, had a signature sports cartoonist, usually summing up the major sports story of the day with pencil, pen and ink. And then there was Murray Olderman, perhaps the most versatile one of them all, who both wrote news stories and features and drew cartoons that were distributed to over 750 newspapers across the country by the Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA).

In the case of Mullin and Darvis in particular, their broadsheet papers allowed them great freedom of space; their cartoons often stretching across four columns to take up nearly half a page. Along with Wohlschlaeger, they were the most frequently used cartoonists by the Sporting News for its front page.

It is probably not coincidental that the golden age of sports cartoonists 1940-64 coincided with the golden age of baseball, especially since the Sporting News, a weekly which early on described itself on its masthead “the Base Ball Paper of the World”, regularly devoted nearly its entire front page during that period with a cartoon.

“Cartoons and cartoonist flourished right up until the ‘70s but began disappearing when all the afternoon papers folded,” said Olderman, who was still drawing cartoons well into his 90s. “We were competing with color photography. That’s what happened with the Sporting News. Sometime in the mid-‘60s, instead of using a Mullin or Darvis cartoon on the front page, they started using color photos. By the ‘80s almost all (the cartoonists) were gone, the one notable exception being the New York Daily News where Bill Gallo, who succeeded the great Leo O’Mealia, continued right up until his death (in 2011).”

Don’t tell the old cartoonists a picture tells a thousand words. Between art and text they were able to sum up everything in their cartoons that was contained in the accompanying 750-1,000-word story. A prime example of that was Gallo’s Aug. 3, 1979 classic in the New York Daily News the day after Yankees catcher Thurman Munson was killed in a plane crash. Surrounded by multiple stories on Munson’s death, Gallo’s cartoon was simple and to the point – Thurman’s face in the sky, looking down as two kids with baseball caps and gloves, in black silhouette, are slowly walking off a baseball diamond, shedding tears, having left their bat lying at home plate, and one of them is saying, “I just don’t feel like playing ball today.” For millions of New Yorkers and Yankee fans, it said it all.

A lot of the cartoonists had their own distinguishing characters which they used to help tell their stories. Gallo had a few of them, most notably his George Steinbrenner depiction, “General Von Steingrabber”, a Prussian general, whip in hand, braided uniform and a helmet with a spike on it, who spoke with a German accent – and “Basement Bertha”, an unkempt washer-woman type he created for the fledgling, originally downtrodden New York Mets.

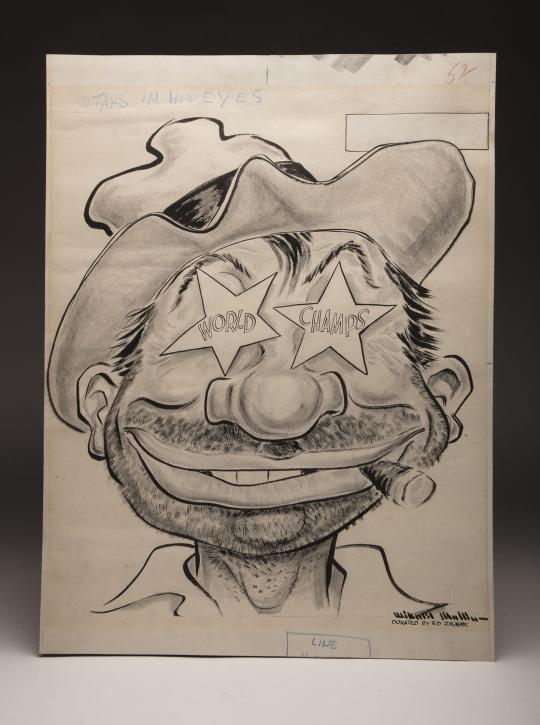

For Mullin, it was “Lenny”, the famous Brooklyn bum, unshaven, with a half lit cigar in his mouth, rumpled hat, tattered jacket, and striped baggy pants who symbolized their perennial also-ran culture (until 1955) and managed to endure long after they left New York for Los Angeles in 1957. (For Los Angeles, Mullin spruced his bum up with sunglasses, a flowered shirt, and a fedora hat.) As Mullin explained the Bum’s origin, he was leaving a Dodger game at Ebbets Field one afternoon to go back to the office to draw his cartoon, and the cab driver said to him: ‘How’d our bums do today?’ A light bulb went off in Mullin’s head and a legend was created.

From that day on, Mullin’s Brooklyn bum appeared in more than a hundred of his hard pencil-and-ink cartoons until the World-Telegram folded in 1966 – as well as on the covers of the Dodger yearbooks in the ‘50s. Even though he was a symbol of losing, Dodger owner Walter O’Malley loved the bedraggled Bum, just as Dodger fans viewed him with affection. Two of Mullin’s most famous Bum cartoons were Don Larsen, at an easel painting his “perfect game” in the 1956 World Series with the bum on the other side of the easel, his back to Larsen, frowning, “it may be art but I don’t like it. It don’t do nuttin’ for me. It don’t even look like me!’; and the cartoon the day after the Dodgers won their first world championship in 1955, which was just the grinning bum’s face with stars instead of his eyes one saying ‘world’ and the other ‘champs’.

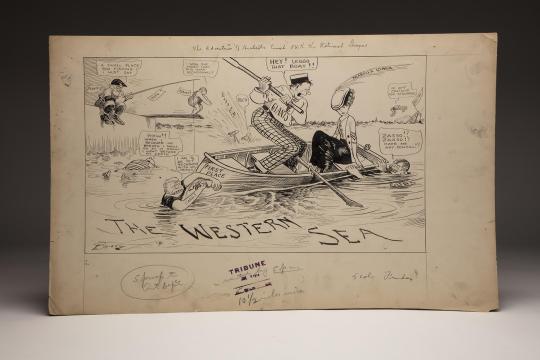

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum preserves almost 500 original baseball cartoons, including approximately 50 – like this one describing the 1914 National League pennant race – by Clare Briggs of the Chicago Herald and Chicago American from the early years of the 20th century. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

“Mullin was clearly the leader of the pack,” says Olderman. “He was very innovative. His style was kind of loosey-goosey. He had great ideas and a great sense of humor.”

If Mullin was the most innovative, Olderman was the most versatile. His artwork ranged from caricatures, to standard editorial cartoons, to brilliant hard pencil and ink portraits. At the same time he wrote – articles to supplement his cartoons, magazine pieces and nearly a-dozen books, including “The 20th Century Encyclopedia of Baseball.”

Since the cartoonists and their works have largely disappeared, a couple of generations of sports fans, who know little about them, were never able to appreciate what is literally a lost art. Fortunately, nearly 500 original baseball cartoons are preserved at the Hall of Fame. The originals are stored in the temperature-controlled archives so as not to expose them to light or changes of temperature and humidity, but there are a handful of reproductions on exhibit in the Museum.

“What makes cartoons unique is their ability to act as ‘snapshots’ of a given place and time while simultaneously providing more commentary than a photograph,” said Erik Strohl, the Hall of Fame’s vice president of Exhibitions and Collections. “Many baseball cartoons had a singular function: To inform readers about the performances of players and clubs. Other cartoons were meant to entice thought on certain topics. Still others reflected the intertwining histories of baseball and the American people.”

The origins of modern cartoons stretch back more than 100 years. One of the most prolific of those early pioneers was Clare Briggs, creator of the first daily comic strip called “A Piper Clerk”, who worked for the Hearst Corporation’s Chicago Herald and Chicago American in the early 1900s. According to Strohl, the Hall of Fame has about 50 of Briggs’ originals, more than any other cartoonist.

“Briggs also incorporated discussion of cultural topics into his baseball cartoons. Like the impact of World War I,” said Strohl. “It is the work of (artists) like Briggs that lead directly to the golden age of cartoons and the likes of Willard Mullin.”

Bill Madden won the BBWAA’s 2010 J.G. Taylor Spink Award