- Home

- Our Stories

- Sylvester Simon bat and glove show the power of perseverance

Sylvester Simon bat and glove show the power of perseverance

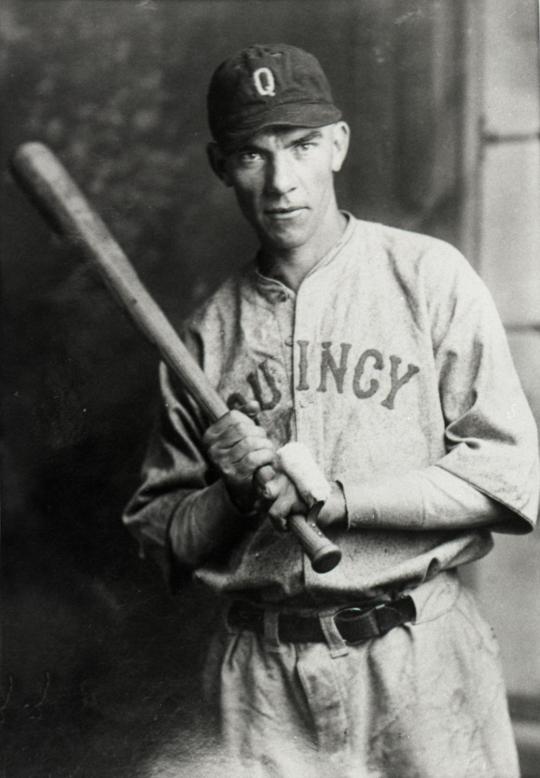

When Sylvester Simon showed up to St. Louis Browns camp in the spring of 1923, scouts gravitated to him like a moth to a light. He showed inordinate power at the plate for a third baseman of his stature (5-foot-10, 170 pounds) and was quick on his feet, seemingly reaching just about every ball sent in his vicinity. But of all his skills, his greatest advantage may have been his hands.

“Simon moves around at third with all the confidence in the world,” wrote the Hamilton Evening Journal. “Nothing is hit too hard for him to try to get. He goes after everything sent in his direction. A big asset is his big hands. Scooping up grounders appears to be play for this youngster. He can throw from any angle.”

By 1924, Simon found himself competing for a regular spot at third. But he wasn’t ready just yet. He would play 23 games for St. Louis that year, before being moved back down to the minor leagues. Even still, the 26-year old showed plenty of promise.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“Syl Simon is one of the likeliest looking youngsters in the game,” wrote St. Louis Browns business manager Bob Quinn. “We will hear of this boy in the future.”

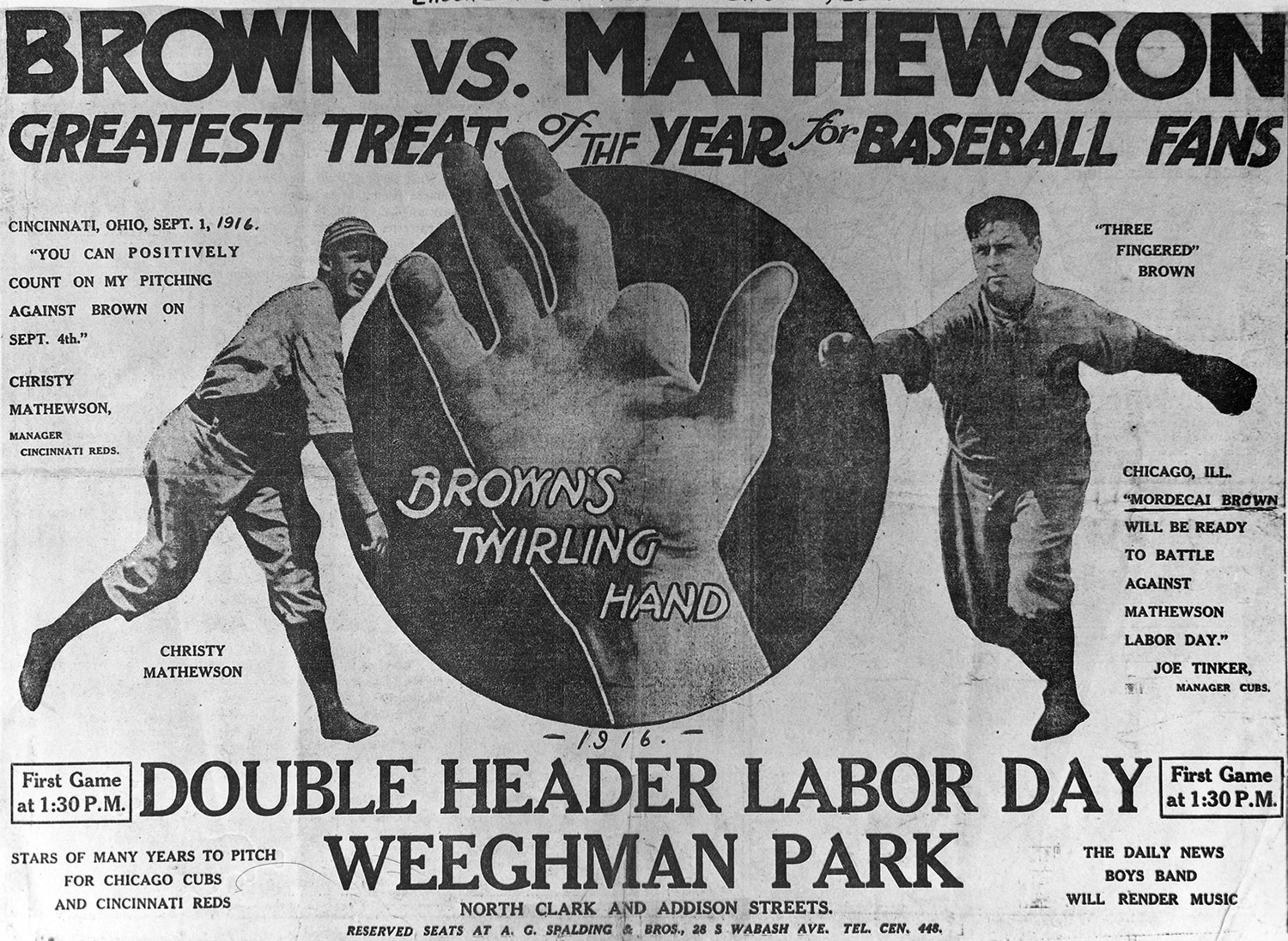

As Quinn predicted, the baseball world would hear of Simon, but not in the way he had originally thought. In the fall of 1926, after playing a full-season for the Double-A Milwaukee Brewers, Simon decided to work in a furniture factory to make some extra money. That decision would ultimately define his major league career, as he suffered a tragic saw accident, losing three fingers on his left hand and part of his palm.

News of the accident spread quickly among the major league ranks, and by the end of that year, Simon received a letter of condolence, a $100 dollar check and a release from then-Brewers owner Otto Borchert. But even though the baseball world had ruled him out, the third baseman still felt he had more to give.

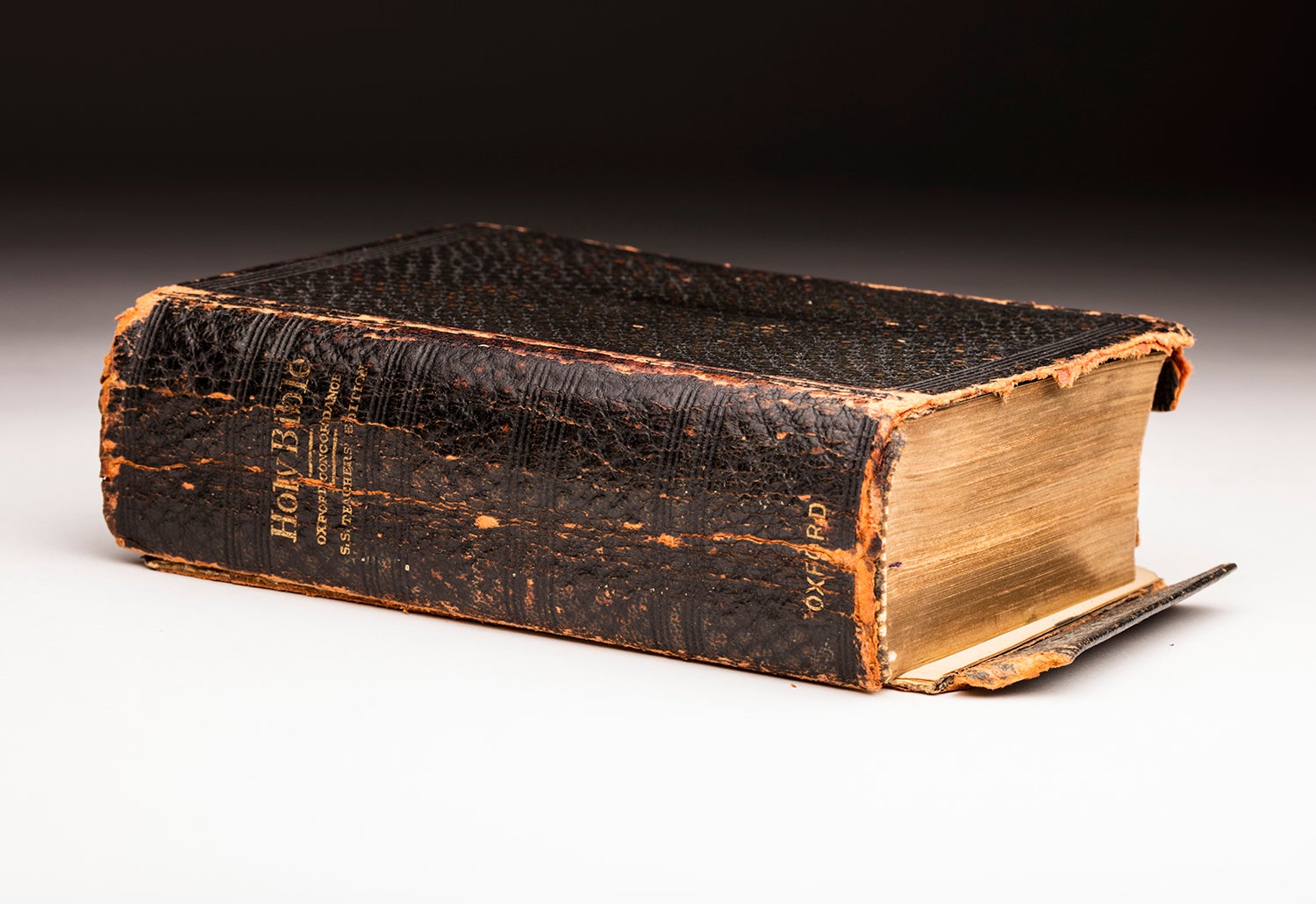

“After the terrific shock of this was over, my husband with some encouragement from us and many friends, devised a special bat and glove so that he was again able to return to baseball,” Thelma Knoll Simon wrote to the Hall of Fame. “He played for seven more years, and his fielding average and batting average was one to be proud of.”

Thelma Knoll Simon donated her husband’s bat and glove to the Hall of Fame in 1962. Of the thousands of bats and gloves at the Hall, it’s safe to say that Simon’s is among the most unusual.

“Draper and Maynard made up and sent him his first glove after he sent them a picture of his hand,” wrote Simon. “They sewed a football knee protector onto the back of the glove to strengthen it where there were no more fingers. Often he would have to glance down to see if he had caught the ball, since there were no fingers to feel with.”

Despite his disability, Simon still managed to record fielding percentages above .900 from 1927 to 1931, averaging .910 for his 11-season career throughout the major and minor leagues. At the plate, he averaged above .300 for four seasons following his accident, reaching a career-high .354 in 1928 and again in 1930 – all while using one hand.

“He experimented with his regular weight bat and had steel hooks made, which he bolted to the bats,” Simon’s wife said. “They were wrapped with adhesive tape and we sewed soft rubber sponges on them and then over that, sewed white flannel, which absorbed the perspiration. Forcing the left hand down between the padded hook and bat it was held tightly, but when he straightened out his little finger he could quickly release and throw the bat and head for first base.”

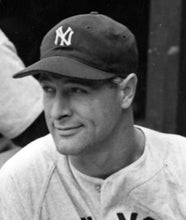

Simon’s relentless determination earned him many loyal fans – Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Kenesaw Mountain Landis among them. But after injuring his arm while playing for the Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League Quincy Indians in 1932, he decided to retire from playing. He’d manage the Indians the following season, but the club went under half-way through the year because of the Great Depression, and Simon retired from pro ball all together.

Nearly 30 years later, his wife’s donation to the Hall of Fame came with specific instructions attached to it.

“Tell youngsters there is no sport with the possibilities of baseball – it truly is our national pastime. Every boy, rich or poor, has a chance to make something of himself,” she wrote. “There are no barriers of race religion or education. If [the glove and bat] can put heart or courage in someone, it will have done double duty.”

Alex Coffey was the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum