- Home

- Our Stories

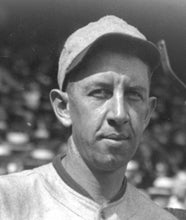

- Smith’s vision helped clear Jackie’s path to majors

Smith’s vision helped clear Jackie’s path to majors

In 1933, the Pittsburgh Courier’s sports editor Chester Washington introduced the “Big League Symposium.” It was a four-month feature that sought to interview and share the opinions of baseball’s leaders about segregation in the majors.

Most executives denied any objections. The first respondent, executive John Heydler, went so far as to claim that baseball had never excluded anyone on the basis of race, creed or color.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

That same year, Wendell Smith, a young Black athlete from Detroit, enrolled in West Virginia State College as a physical education major. Smith played for the Yellow Jackets’ baseball and basketball teams and, though he excelled on the court and the diamond, it was behind the scenes that he hit his stride. As the West Virginia football team publicist and sports columnist for the campus paper, the Yellow Jacket, Smith was well prepared to join the news industry upon his graduation. In 1937 he was hired by the Courier and joined Washington in his campaign to allow Black players into the major leagues. Soon, fueled by his regular columns, Smith became the paper’s most outspoken advocate for breaking baseball’s color barrier.

The Courier continued to grow rapidly, increasing its circulation from 46,000 to over 250,000 between 1933 and 1946. During that time, Smith was promoted twice, first to assistant sports editor in 1938 and then to sports editor in 1940. On Feb. 7, 1942 the paper debuted its “Double V” campaign, which highlighted the hypocrisy of Black soldiers fighting in a war for freedoms that still remained inaccessible to them at home. They specifically tied the campaign to the integration of Major League Baseball, with Smith writing about how “Big league baseball is perpetuating the very things thousands of Americans are overseas fighting to end, namely, racial discrimination and segregation.” “The goal is in sight,” Smith wrote that July. “The rest is up to you, Mr. and Mrs. Fan. In every town, village and hamlet, fans must organize clubs and join the fight. The first part of the battle has been won, but it will take concentrated, nationwide action to conquer the stubborn club owners of the majors.”

Black newspapers around the country continued to advocate fervently for integration, and their constant pressure inspired tryouts facilitated or prompted by the sportswriters. In Aug. of 1942, Pittsburgh Pirates President William Benswanger asked Smith for a recommendation of four Black players to attend a tryout the following month. Smith named Josh Gibson, Willie Wells, Sam Bankhead and Leon Day, but Benswanger rescinded his offer before the quartet could audition. A few years later, in 1945, Joe Bostic and Jimmy Smith arranged a tryout with the Brooklyn Dodgers and that same year Smith orchestrated a tryout with the Boston Braves and Red Sox.

“I sincerely hope that we did not inconvenience you in any way and that our pleasant but short relationship will be resumed again in the near future,” Smith wrote to Red Sox general manager Eddie Collins in a letter preserved in the Hall of Fame’s archives.

“I will appreciate it if you will let me know what decision, if any, has been made in regards to the three players – Jackie Robinson, Samuel Jethroe, and Marvin Williams.”

Smith recommended Robinson again shortly after the Boston tryout, this time to Brooklyn Dodgers President Branch Rickey. Rickey signed the then-Kansas City Monarch to a contract with the Montreal Royals, one of the Dodgers’ farm teams, on Oct. 23, 1945.

The following winter, when Robinson and his wife, Rachel, traveled to Florida for Spring Training, Smith joined them in Daytona Beach.

“I am most happy to feel that you are relying on my newspaper and me, personally, for cooperation in trying to accomplish this great move for practical Democracy in the most amiable and diplomatic manner possible,” Smith wrote to Rickey in a letter dated Jan. 14, 1946. He arranged for Robinson’s housing and travel that season, both in Florida and with the Royals, in large part to help navigate the segregationist policies for hotels and buses. Through the year, Smith continued to publish regular updates on what would be Robinson’s International League championship season.

“Never before in history have Negro athletes made such great gains as they did in 1946,” Smith published in his “Sports Beat” column from Jan. 4, 1947.

“At the top of the list, of course, is Jackie Robinson, who is ‘Athlete of the Year’ and the 1946 International League batting champion. Robinson has proved his worth in the minors and is definitely ready for the big leagues. If he makes the Dodgers – and we are confident he will – it will climax a long and unceasing fight for Negroes in the majors.”

Sure enough, on April 15, 1947 Jackie Robinson made his major league debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

“[Dodgers manager Clyde] Sukeforth was talking about the Yankees,” Robinson recalled in Smith’s column from April 19. “Then suddenly he looked over the bunch of players sitting in front of me and said – ‘Robinson, how are you feeling today?’ The question was popped so fast I was startled at first. When I finally answered, I said I felt fine. Sukeforth said: ‘Okay, then you’re playing first base for us today!’” Robinson and Smith continued to work closely after Robinson made his debut. During that 1947 season, the Courier ran a column, “Jackie Robinson Says,” under Robinson’s bio but ghostwritten by Smith, and in 1948 the duo published “Jackie Robinson: My Own Story”. They drifted apart as the years wore on, with Robinson rising to baseball superstardom and Smith moving to Chicago to write for the Chicago Herald-American and Chicago Sun-Times, and later transitioning to television as a sports anchor with WGN.

Despite the separation, the two remained almost fatefully intertwined. When Robinson passed away in 1972, it was Smith who penned the Hall of Famer’s obituary.

It was the final story Smith wrote. He passed away from pancreatic cancer just one month after Robinson.

“Everywhere we went, Wendell Smith was there,” Dodgers pitcher Don Newcombe recalled later on. “He was instrumental in so many things that happened.”

Wendell Smith, who was one of the first Black sportswriters to be admitted to the Baseball Writers’ Association of American in 1948, was posthumously selected as the 1993 BBWAA Career Excellence Award winner and reunited with Jackie Robinson in Cooperstown.

Isabelle Minasian was the digital content specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum