I never really liked to stand in front of all of you and talk about what I was doing. I enjoyed doing those things but that’s what I was getting paid to do, that’s what I worked hard to do, and so the Hall of Fame was never something that I surely ever thought about. I just really enjoyed playing the game. I truly did.

- Home

- Our Stories

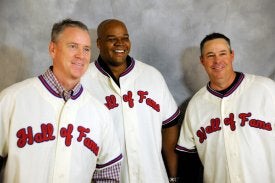

- Hall of Fame Class of 2015

Hall of Fame Class of 2015

It is the most exclusive club in sports, and election to the Baseball Hall of Fame means that you have become immortal to the fans of the game.

The oak walls of the Hall of Fame Plaque Gallery in Cooperstown are lined with the bronze plaques that tell the stories of the men and women who have shaped our National Pastime. Since 1983, Matthews International in Pittsburgh has been the exclusive provider of those plaques. From the initial clay sculpting to the final touch-ups, Matthews takes great pride in their role in the annual induction ceremonies. Many people are involved in the creation of the plaques. In the video below, a few of them tell the story of the process.

The permanence of the bronze plaques is a testament to each Hall of Fame member’s impact on the game. For generations, the Gallery has been and will continue to be the ultimate tribute to legendary baseball careers.

Immortalized in Bronze

Voting Results

| Ballots Cast: 549 | Needed for Election: 412 |

| Votes | Player | Percentage |

| 534 | Randy Johnson | 97.3% |

| 500 | Pedro Martinez | 91.1% |

| 455 | John Smoltz | 82.9% |

| 454 | Craig Biggio | 82.7% |

| 384 | Mike Piazza | 69.9% |

| 306 | Jeff Bagwell | 55.7% |

| 302 | Tim Raines | 55.0% |

| 215 | Curt Schilling | 39.2% |

| 206 | Roger Clemens | 37.5% |

| 202 | Barry Bonds | 36.8% |

| 166 | Lee Smith | 30.2% |

| 148 | Edgar Martinez | 27.0% |

| 138 | Alan Trammell | 25.1% |

| 135 | Mike Mussina | 24.6% |

| 77 | Jeff Kent | 14.0% |

| 71 | Fred McGriff | 12.9% |

| 65 | Larry Walker | 11.8% |

| 64 | Gary Sheffield | 11.7% |

| 55 | Mark McGwire | 10.0% |

| 50 | Don Mattingly | 9.1% |

| 36 | Sammy Sosa | 6.6% |

| 30 | Nomar Garciaparra | 5.5% |

| 21 | Carlos Delgado | 3.8% |

| 4 | Troy Percival | 0.7% |

| 2 | Aaron Boone | 0.4% |

| 2 | Tom Gordon | 0.4% |

| 1 | Darin Erstad | 0.2% |

| 0 | Rich Aurilia | 0.0% |

| 0 | Tony Clark | 0.0% |

| 0 | Jermaine Dye | 0.0% |

| 0 | Cliff Floyd | 0.0% |

| 0 | Brian Giles | 0.0% |

| 0 | Eddie Guardado | 0.0% |

| 0 | Jason Schmidt | 0.0% |

*All candidates in italics received less than 5% of the vote on ballots cast and will be removed from future BBWAA consideration

The image is forever captured on video, and locked in the hearts of anyone who stepped in the batter’s box against Randy Johnson.

It was the 1993 All-Star Game in Baltimore, and the Phillies’ John Kruk – a left-handed hitter – came to the plate in the third inning against the 6-foot-10 Johnson, the game’s most dominant left-handed pitcher. The next thing Kruk knew, a fastball breezed over his helmet.

Kruk managed a grin, grabbed his jersey to indicate his heart was palpitating…and swung feebly at two outside pitches to end the at-bat with a strikeout. Kruk later called the at-bat a success – because he had survived.

For Johnson, it was one moment of many that defined him as one of the most intimidating pitchers of all-time – and one of the greatest of his generation.

Today, Randy Johnson is a Hall of Famer.

Born Sept. 10, 1963 in Walnut Creek, Calif. – a San Francisco suburb – Johnson was an elite athlete who used his height to his advantage in both baseball and basketball. He turned down the Atlanta Braves after they drafted him in the fourth round in 1982, opting for a combination baseball/basketball scholarship at the University of Southern California.

Johnson began concentrating solely on baseball following his sophomore year and was drafted by the Expos in the second round in 1985. This time, Johnson turned pro.

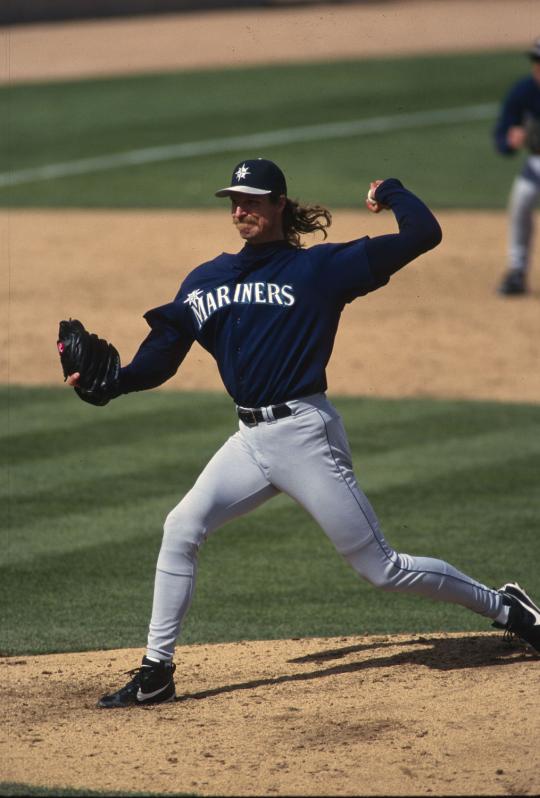

By 1988, the Expos has brought Johnson to the big leagues – making Johnson the tallest player in big league history. But midway through the 1989 season, Montreal dealt Johnson to the Seattle Mariners in a trade that brought star lefty Mark Langston to the Expos. For the next three-and-half years, Johnson struggled to find his control – showing spurts of dominance (including his June 2, 1990 no-hitter against the Tigers) while leading the American League in walks three times.

In August of 1992, Johnson sought out the Rangers’ Nolan Ryan, who was nearing the end of his Hall of Fame career. Ryan suggested that Johnson make a few adjustments to his delivery, and on Sept. 27 Johnson faced Ryan in a game at Arlington Stadium. Johnson threw 160 pitches in eight innings, striking out 18 Rangers in a game Texas won 3-2.

From virtually that point on, Johnson was a different pitcher.

In 1993, Johnson went 19-8, led the AL with 308 strikeouts and finished second in the league’s Cy Young Award voting. After a 13-6 record in the strike-shortened 1994 season (when he again led the AL in strikeouts with 204), Johnson went 18-2 in 1995 while striking out 294 batters, leading the league with a 2.48 earned-run average and winning the first of his five Cy Young Awards.

Johnson missed most of the 1996 season after undergoing back surgery, but rebounded in 1997 to go 20-4 with 291 strikeouts. But with his contract up following the 1998 season, Johnson was traded midway through ’98 to the Astros – where he went 10-1 with a 1.28 ERA in 11 starts, leading Houston to a playoff berth.

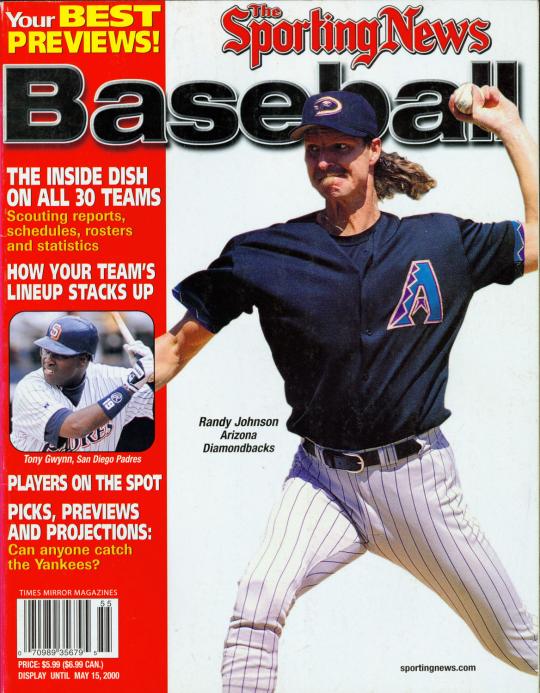

As a free agent following the playoffs, Johnson was one of the most sought-after players in the game. But at 35 years old, some thought Johnson’s best days were behind him. Instead, they were just beginning.

Johnson signed a four-year deal with the Diamondbacks, and the second-year club instantly gained credibility – not to mention a legitimate ace. From 1999-2002, Johnson captured four straight National League Cy Young Awards, three ERA titles and struck out at least 334 batters each season. The ultimate triumph came in 2001 when Johnson was 21-6 in the regular season, then posted a 3-0 record in the World Series – sharing the Most Valuable Player honors with Curt Schilling and leading Arizona to a seven-game series win over the Yankees.

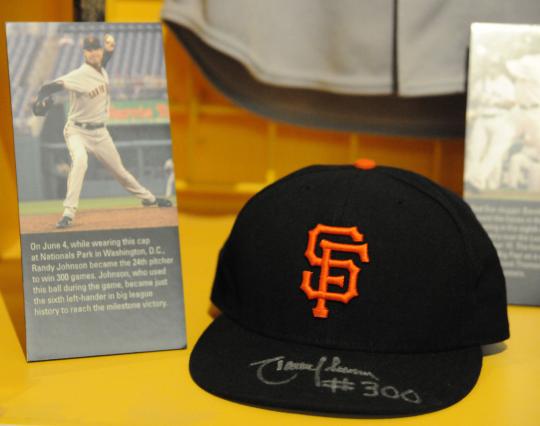

Johnson remained with the Diamondbacks through the 2004 season before Arizona traded the 41-year-old fireballer to the Yankees. Johnson won 34 games in two seasons with New York before heading back to the Diamondbacks for two more seasons. He finished his career in 2009 with the Giants, where he won his 300th career game.

After he signed with Arizona prior to the 1999 season, Johnson posted more than half – 160 – of his 303 career victories.

In 22 seasons, Johnson led his league in strikeouts nine times, earned four ERA titles and recorded 100 complete games to go along with 37 shutouts. He was named to 10 All-Star Games, and only four left-handed pitchers (Warren Spahn, Steve Carlton, Eddie Plank and Tom Glavine) have ever won more games.

His 4,875 strikeouts rank No. 2 all-time behind Ryan’s 5,714, and his 10.61 strikeouts per nine innings rank first all-time. Johnson owns six of the 33 300-strikeout seasons in the modern-era history of the game. Five of the top 11 single-season strikeout seasons belong to the pitcher known as the Big Unit.

At every stop in his baseball journey, Pedro Martinez was told he lacked the size to be a dominant starting pitcher.

And at every stop, the modest-looking right-hander – with huge hands and a heart to match – dominated opposing hitters like few ever have.

Now, Martinez makes the final stop on his baseball journey in Cooperstown.

Born in Manoguayabo, Dominican Republic, on Oct. 25, 1971, Martinez grew up with five brothers and sisters in a one-room home on the outskirts of Santo Domingo. His talent – and that of his brother, Ramon Martinez – soon attracted pro scouts.

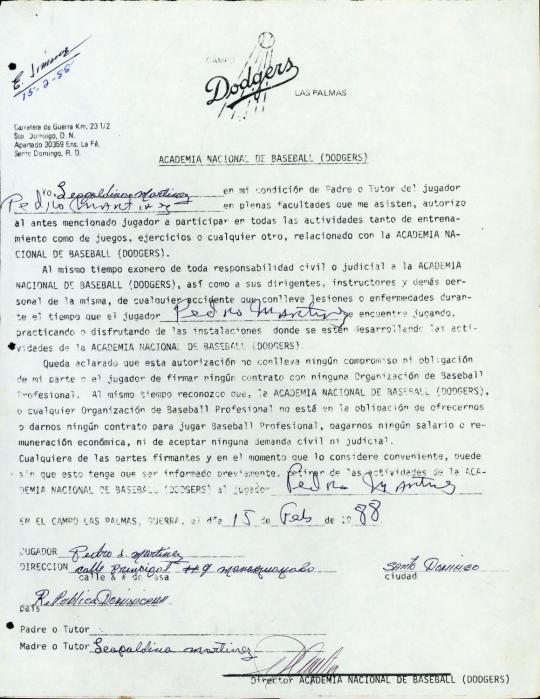

Ramon signed with the Dodgers on Sept. 1, 1984. Pedro followed Ramon to Los Angeles, signing with the Dodgers on June 18, 1988. By 1990, Ramon was a 20-game winner in the big leagues – and Pedro was one of the Dodgers’ top prospects, despite his 5-foot-10 frame that carried less than 150 pounds in those days.

In 1993, Pedro Martinez got regular work in the Dodgers’ bullpen, posting a 10-5 record in 65 games while striking out 119 batters in 107 innings. But following the season, the Dodgers traded Martinez to the Expos for second baseman Delino Deshields. After harnessing his explosive fastball over the next two seasons – which included a June 3, 1995 game where he retired the first 27 Padres batters he faced before allowing a hit in the bottom of the 10th – Martinez was named to his first All-Star Game in 1996 and then exploded onto the national scene the following year. In 1997, Martinez went 17-8 with a National League-best 1.90 earned-run average and 13 complete games, striking out 305 batters en route to his first Cy Young Award.

His combination of a 97-mph fastball, devastating change-up and pinpoint control made Martinez nearly unhittable.

But the Expos, knowing Martinez could become a free agent after the 1998 season, traded their ace to the Red Sox just days after he won the Cy Young. The Sox immediately locked up Martinez for the next seven seasons, setting in motion a virtually unprecedented string of success for the team and the pitcher.

Martinez went 19-7 in 1998 and finished second in the American League Cy Young Award vote, then posted a season for the ages in 1999 – going 23-4 with a league-best 2.07 ERA and 313 strikeouts, winning the pitching Triple Crown. He became just the eighth pitcher to post two 300-strikeout seasons, set a new mark (since broken) with 13.2 strikeouts per nine innings and finished second in the AL Most Valuable Player voting.

By some standards, 2000 was even better. Martinez went 18-6 that year with a 1.74 ERA and 284 strikeouts. He allowed just 128 hits in 217 innings pitched en route to a WHIP (walks plus hits divided by innings pitched) of 0.737 – by far the best single-season mark in big league history. He accomplished all this in one of the most prolific offensive eras in baseball history and pitching on a home field (Fenway Park) that ranks as one of the most hitter-friendly in the game’s history.

Martinez capped 2000 by winning his third Cy Young Award in four years. He battled shoulder problems in 2001, but rebounded in 2002 with a 20-4 record, again leading the AL in ERA (2.26) and strikeouts (239). He finished second in the Cy Young Award voting, becoming the first pitcher to lead his league in ERA, WHIP (0.923), strikeouts and winning percentage (.833) and not win the Cy Young.

I’m very honored and I dedicate it to every fan out there and every teammate that I played for.

After leading the league again in WHIP, ERA and winning percentage in 2003 en route to a 14-4 mark, Martinez began showing wear and tear in 2004 – posting a 3.90 ERA while going 16-9. But Martinez still finished fourth in the Cy Young Award voting – and helped the Red Sox end 86 years of frustration when they captured the World Series title for the first time since 1918. Martinez’s seven shutout innings in Game 3 on the road in St. Louis gave the Sox a commanding 3-games-to-0 lead and effectively wrapped up the title.

Martinez signed a free agent contract with the Mets following the World Series, going 15-8 with a 2.82 ERA in 2005 while giving his new team – which lost 91 games in 2004 – instant credibility. The following year, Martinez battled a nagging toe injury and was eventually shelved with a shoulder injury while going 9-8 – but was instrumental in a Mets’ season that featured a appearance in the National League Championship Series.

After two more injury-filled seasons – including the 2007 campaign that featured his 3,000th career strikeout – Martinez sat out the first part of the 2009 season before signing with the Phillies to help their postseason push. He went 5-1 in nine regular-season starts – becoming the 10th pitcher to win at least 100 games in both leagues – then threw seven shutout innings against his old Dodgers club in the NLCS.

He explored pitching again in 2010 and 2011, but never returned to the majors and announced his retirement on Dec. 4, 2011.

The eight-time All-Star finished his career with a record of 219-100, good for a winning percentage of .687 that is sixth all-time and trails only Whitey Ford’s .690 among modern-era pitchers with at least 150 victories. He won five ERA titles en route to a career mark of 2.93, captured six WHIP titles (his career WHIP of 1.054 ranks fifth all-time and is the best of any modern-era starter) and averaged 10.04 strikeouts per nine innings (third all-time behind Randy Johnson and Kerry Wood).

His 3,154 strikeouts rank 13th all-time, and his strikeout-to-walk ratio of 4.15-to-1 ranks third all-time.

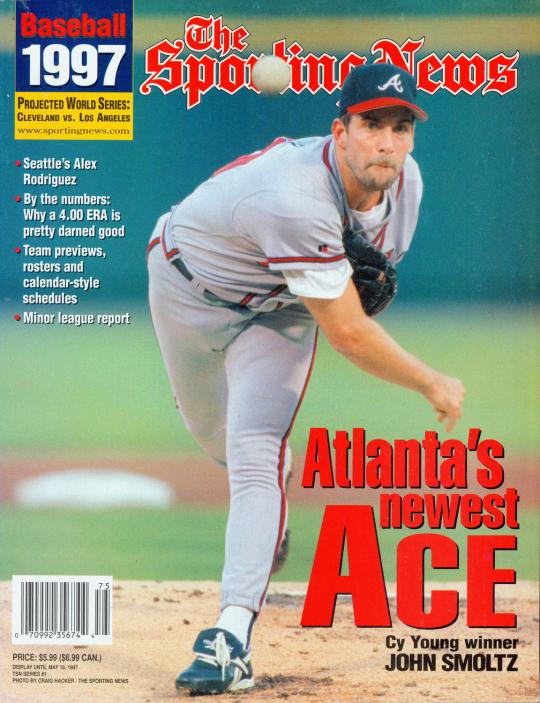

John Smoltz was a major cog in a stellar pitching triumvirate, a three-headed force that led the Atlanta Braves to unprecedented success. Eventually, arm injuries led to his transition into a reliever, where he proved to be one of the game’s best.

Now, Smoltz is reunited with his Braves teammates in Cooperstown as a member of the Hall of Fame

Dealt to the Braves when he was a minor league prospect, Smoltz soon established himself as a workhorse right-handed hurler for a young team on the verge of turning the corner. Unfortunately, in the midst of this prolonged success, a troublesome elbow forced the starter to become a closer for a few years. Smoltz would emerge from this unchartered path to become the only player in big league history with at least 200 career wins and at least 150 saves.

Born May 15, 1967 in Detroit, Mich., John Andrew Smoltz grew up in a baseball family with both a grandfather and his father having spent time working at Tiger Stadium. Smoltz was such a big Tigers fans growing up that after Detroit won the 1984 World Series, he and his father dug up a piece of Tiger Stadium sod and planted it in the family’s backyard.

Starring in both baseball and basketball at Waverly High School in Lansing, Mich., Smoltz’s initial plan was to attend Michigan State to play both sports. Instead, he signed with his hometown Tigers after being selected in the 22nd round of the 1985 amateur draft.

“This is an honor that I could not have anticipated when I started playing baseball and even today. I think it will hit me when I get there. I’m not comfortable with titles but I’m relishing this one and I will for the rest of my life.

After almost two seasons toiling in the Tigers’ minor league farm system, the 20-year-old Smoltz was acquired by Atlanta Braves general manager Bobby Cox for veteran pitcher Doyle Alexander on August 12, 1987. At the time of the transaction, Smoltz was 4-10 with a 5.68 ERA pitching for the Double-A Glens Falls Tigers of the Eastern League, while Alexander, 36, was a 16-year veteran with a 5-10 record and a 4.13 ERA in 16 starts for the Braves.

In 1987, Alexander went 9-0 with a 1.53 ERA during his seven weeks with a Detroit team that would qualify for the postseason, but the Tigers would lose in the ALCS to the Twins in five games. By the next year, and after only a half-season at Triple-A Richmond, Smoltz was pitching in the majors, finishing with a 2-7 won-loss record. Only one season later, he was pitching in the All-Star Game.

Over his first five full seasons, from 1989 to 1993, Smoltz averaged 14 wins, 34 starts and 182 strikeouts with a 3.42 ERA. This stretch also included the Braves’ remarkable 1991 campaign, a worst-to-first season in which Atlanta lost an epic seven-game World Series title to the Minnesota Twins. The ’91 Fall Classic is arguably most remembered for Jack Morris’ 10-inning masterpiece in Game 7, shutting out the Braves, 1-0, where Smoltz tossed 7 1/3 scoreless innings while earning a no-decision.

Smoltz’s pitching repertoire included a trio of exceptional pitches: an impressive fastball, a slider that veered away from right-handed batters, and a splitter that darted under the swings of left-handed batters.

Led by the “Big Three” of Smoltz, Greg Maddux and Tom Glavine, the postseason would become quite familiar for Atlanta. Smoltz, who would became the only Braves player to be part of the franchise’s historic run of 14 consecutive division titles from 1991 to 2005, would appear in 41 postseason games, compiling a 15-4 record, a 2.67 ERA and a record 199 strikeouts. In five World Series, including the 1995 triumph over the Indians, Smoltz started eight games, finishing with a 2-2 record and a 2.47 ERA.

Plagued by arm problems throughout his big league career, the first of a half-dozen surgeries took place in September 1994 when doctors removed a large bone spur and some chips from the back of his right elbow.

Two years later, Smoltz captured the 1996 National League Cy Young Award on the strength of a 24-8 record (including 14 consecutive wins from April 9 to June 19), a 2.94 ERA and a league-best 276 strikeouts. Smoltz capturing the award also ended Maddux’s Cy Young streak at four, giving the Braves four straight winners. And with Glavine’s wins in 1991 and 1998, Braves pitchers won six Cy Young awards in eight years.

Despite having arthroscopic elbow surgery to remove bone chips prior to the season and a four-week disabled list stint with an inflamed elbow during the season, a resilient Smoltz finished 1998 with a 17-3 record. The following year, spending time on the DL twice with a strained elbow, he tried to compensate for the pain by dropping down his pitching motion from overhand to a three-quarters delivery to finish 11-8.

The worst of Smoltz’s injuries came in 2000 when he missed entire season after tearing the medial collateral ligament in his right elbow in spring training and undergoing Tommy John surgery in March. A comeback in 2001 was derailed after five starts with time spent on the DL, but when he returned in July he was converted into a relief pitcher as the best chance to maximize his health.

After 159 wins as a stalwart starting pitcher for the Braves, the versatile Smoltz began anew as the team’s closer and the results were superb. Finishing out the 2001 season as the team’s new fireman, he had 10 saves in 11 chances with a 1.59 ERA.

In 2002, his first full season in the closer role, Smoltz set the NL record by converting 55 saves (tied by the Dodgers’ Eric Gagne in 2003). Similar to his success as a starting pitcher, he would dominate his new role in the bullpen by saving 154 games in 168 opportunities in his 3½ seasons as an elite closer. Injuries continued to be a concern during this period as well, as he suffered from right elbow tendinitis in 2003 and had right elbow surgery in October 2004 to clean up scar tissue.

Preferring to be a starter, Smoltz was a workhorse after returning to the rotation in 2005, averaging 15 wins and 222 innings over the next three seasons. But two months after winning his 200th career game in May 2007, he was back on the DL with right shoulder tendinitis.

After five starts early in the 2008 season, one of which included him becoming the 16th big league pitcher to reach 3,000 career strikeouts, it was announced that Smoltz would need season-ending shoulder surgery.

Signed as a free agent by the Red Sox in January 2009, Smoltz went 3-8 in a season split between Boston and the Cardinals.

An eight-time All-Star and the winner of the 1997 NL Silver Slugger Award (pitcher), Smoltz finished his 21-year big league career with a 213-155 record, 154 saves, 3,084 strikeouts and a 3.33 ERA. The winner of 14 or more games 10 times he twice led the NL in wins (1996 and 2006), innings pitched (1996 and 1997) and strikeouts (1992 and 1996).

Also honored for his humanitarian efforts, Smoltz has been honored with the 2005 Lou Gehrig Memorial Award (2005), the Roberto Clemente Award (2005) and the 2007 Branch Rickey Award (2007).

Craig Biggio’s path to big league stardom took him from high school football standout to a position change many in baseball thought was all but impossible.

Along the way, Biggio amassed seven All-Star Game selections, 3,060 hits and the admiration of fans and teammates.

Today, he joins the game’s legends in Cooperstown

Born Dec. 14, 1965 in Smithtown, N.Y., Biggio starred at Kings Park High School on Long Island in football, and seemed destined to become one of the top recruited running backs in the nation. But baseball beckoned, and he accepted a partial baseball scholarship to Seton Hall University – quickly establishing himself as a pro prospect. In 1987, he was taken in the first round (22nd overall pick) by the Houston Astros in the MLB Draft.

After just 141 minor league games over parts of two seasons – during which he compiled a .344 batting average – Biggio was called up to the Astros in June of 1988. He played in 50 games that summer, then took over as Houston’s regular catcher in 1989 – hitting 13 homers and adding 60 RBI while winning the National League’s Silver Slugger Award for catchers.

By 1991, Biggio was a .295 hitter who had made his first All-Star team. And quickly, there was talk about moving him from behind the plate in order to lengthen his career.

In 1992, he became Houston’s second baseman – appearing in all 162 games and making his second All-Star team.

This is something that is very overwhelming and humbling. To be part of an organization for 20 years is something for me that was really special and I loved being part of, so obviously getting to go in the Hall of Fame as an Astro is something that I’m very, very proud of for my family, the organization and most of all for the fans.

Biggio made the virtually unprecedented move look easy. From 1993-99, Biggio grew into more power at the plate without sacrificing his speed. He averaged better than 17 homers and 33 steals a year while averaging more than 116 runs scored per season as Houston’s leadoff hitter. He also continued to thump doubles at a record pace en route to 668 for his career – good for fifth on the all-time list.

Then in 2003, Biggio again changed positions – this time heading to center field when Jeff Kent came to Houston as a free agent. Biggio spent two years in the outfield before moving back to second base for the final three years of his career.

Biggio joined the 3,000-hit club in 2007, his last year in the big leagues. In all, he spent 20 seasons with the Astros, hitting .281 with 1,844 runs scored (15th all-time), 291 home runs and 414 stolen bases. He was hit by a pitch 285 times – second most all-time – won five Silver Slugger Awards (one at catcher and four a second base) and four Gold Glove Awards at second base (1994-97).

He is the only player in baseball history with at least 3,000 hits, 600 doubles, 400 stolen bases and 250 home runs.

Class of 2015 Inductee Exhibit

The 2015 Inductees exhibit is open at the Hall of Fame, and will remain on display through May 2016 when a new class of inductees is celebrated in the Museum.

The exhibit, featuring one display for each member of the Hall of Fame Class of 2015, is located on the first floor of the Museum as visitors approach the Plaque Gallery.

Some of the artifact highlights contained in the Class of 2015 exhibit include:

Craig Biggio

• Cap when he became the 27th player in major league history to record 3,000 hits on June 28, 2007

• Jersey from Opening Day in 2003, when he became the Houston Astros’ regular center fielder – the third full-time position of his career

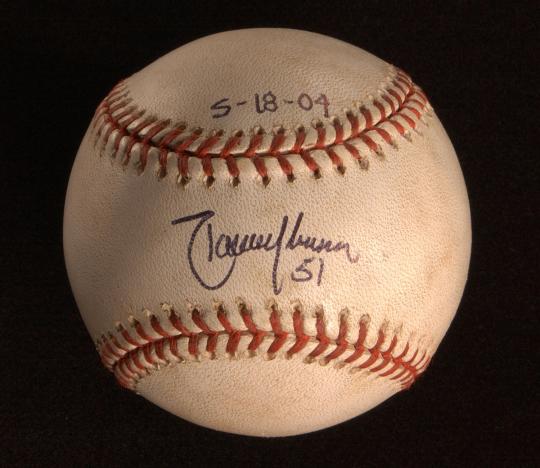

Randy Johnson

• A baseball from perfect game, a 2-0 victory against the Atlanta Braves, on May 18, 2004

• Cap from the 2001 World Series, when he went 3-0 and shared co-MVP honors with teammate Curt Schilling in the Arizona Diamondbacks’ thrilling seven-game victory against the New York Yankees

Pedro Martinez

• Jersey when he struck out five of the first six National League hitters he faced in the 1999 MLB All-Star Game at Fenway Park

• Cap from Game 3 of the 2004 World Series, when he pitched seven shutout innings against the St. Louis Cardinals and helped the Boston Red Sox win their first Fall Classic title in 86 years

John Smoltz

• 1996 NL Cy Young Award

• Jersey when he recorded his 55th save against the New York Mets on Sept. 28, 2002 to set the current NL standard for most saves in a single season

Fans can see all these artifacts and more in the Inductees exhibit as part of regular admission to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Visitors will also be able to visualize the Class of 2015’s achievements thanks to a new highlight video display as part of this year’s exhibit.

Class of 2015 Reactions

Randy Johnson

“I never really liked to stand in front of all of you and talk about what I was doing,” Johnson said. “I enjoyed doing those things but that’s what I was getting paid to do, that’s what I worked hard to do, and so the Hall of Fame was never something that I surely ever thought about. I just really enjoyed playing the game. I truly did."

“As a professional athlete, no matter what sport you played, you want to be able to go out there and compete at your best,” he added. “There were games where I would pitch good, but in any sport you need to be consistent, so for every good game I would go out and pitch I would pitch a couple of bad ones. Until about 1992, 1993 in Seattle did I become a little bit more consistent with my mechanics and my release point. And then when I did become consistent with my mechanics and my release point, it then really became a lot of fun. I could compete and utilize my God-given ability and I wasn’t fighting myself as much out there.”

Pedro Martinez

“I’m very honored,” said Martinez. “And I dedicate it to every fan out there and every teammate that I played for.”

Martinez, at 5-foot-11 and 170 pounds, was a different sized pitcher than fellow inductee Johnson, he was listed at 6-foot-10.

“I was aggressive and I considered myself a power pitcher with some finesse,” Martinez said. “Because of my size, I was able to coordinate a little bit easier, my mechanics, because I’m easier to balance on the mound because of the small frame. But I can’t imagine being as tall as Randy and having to fine tune his craft. To me it’s now clear why it took him a little while to get it all together. Being so tall it’s not easy to coordinate all that, to find a release point that depends on one or two inches all the time. For me I think it was a little bit easier because I didn’t have that problem with height."

“Randy was one of the guys I would stay on the top step of the dugout to watch him pitch. Exciting, the most dominant lefty I’ve ever seen. Always a treat to go see Randy pitch.”

John Smoltz

“This is an honor that I could not have anticipated when I started playing baseball and even today,” said Smoltz during a media conference call each of the day’s honorees would eventually hold on Tuesday. “I just want to thank the Baseball Writers’ Association of America for giving me their vote of confidence to be enshrined in the greatest Hall of Fame that we have."

“I think it will hit me when I get there. I’m not comfortable with titles but I’m relishing this one and I will for the rest of my life."

“I stayed away from asking them [former teammates Maddux and Glavine] any Hall of Fame questions for a lot of reasons. I didn’t want to do anything until this day came, and it has come, so there will be a variety of questions that I’ll have as time goes on,” Smoltz added. “I enjoyed last year so much, I can’t even put into words the appreciation I had for the Hall. I couldn’t believe how many people were there, I couldn’t believe how unique and neat that town is, and not to mention I got a chance afterwards, while they were at dinner by the way, to play golf at that golf course by myself in an hour and 40 minutes. It was like a little slice of heaven.”

Craig Biggio

“I want to thank the Baseball Writers’ Association for this huge honor,” said Biggio. “This is something that is very overwhelming and humbling. To be part of an organization for 20 years is something for me that was really special and I loved being part of, so obviously getting to go in the Hall of Fame as an Astro is something that I’m very, very proud of for my family, the organization and most of all for the fans."

“Twenty years is a long time in one city and you develop many, many relationships and a big fan base, and to be able to give that back to them at the end here, to be able to get a guy in the Hall of Fame, I’m very honored and humbled to be able to give that to them. To be able to finally get an Astro guy in there, I take a lot of pride in that for a lot of reasons, including all the players who’ve put an Astros uniform on.”

As for last year, when he came so close to being elected to the Hall of Fame, Biggio said he was totally fine.

“You’re trending in the right direction but you never know which way you’re going to go. I didn’t take it for granted,” he said. “It was a very emotional phone call when I received the news. I just loved playing the game of baseball, every minute of it, every inning of it, and obviously now, to be inducted into the Hall of fame, it’s very, very special. I’m overwhelmed by it right now.”