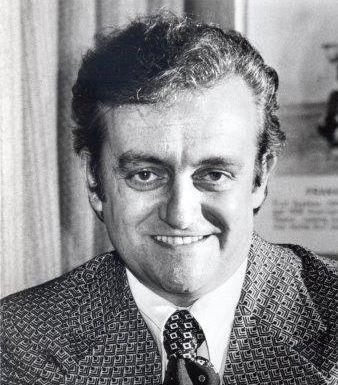

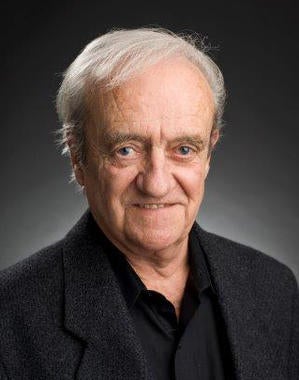

Roland Hemond built contenders, mentored generations

Roland Hemond began his baseball career as a stadium sweeper in Hartford, Conn. Decades later, he would be known as one of the most respected executives in the game.

In between, Hemond was an invaluable mentor to countless executives, managers and players.

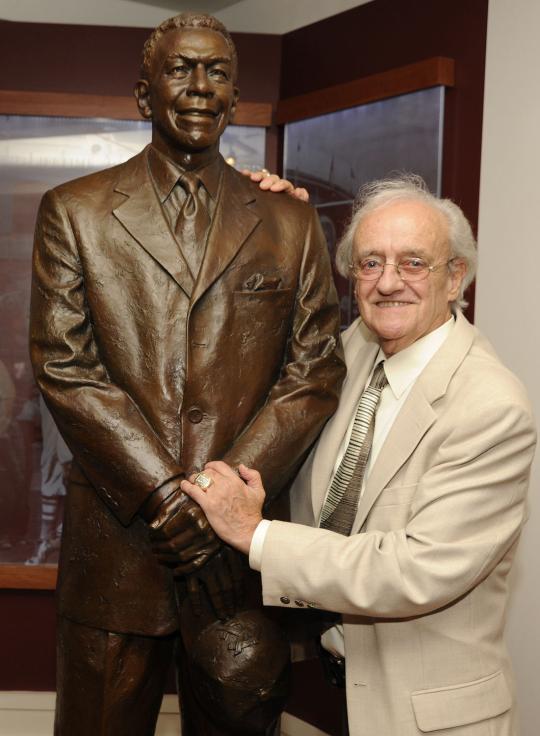

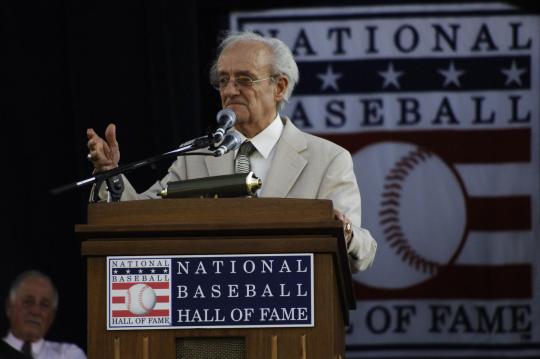

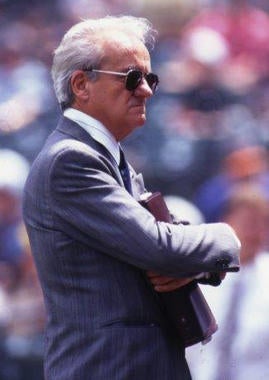

Hemond, the Hall of Fame’s 2011 Buck O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award winner, died Sunday, Dec. 12, at the age of 92. In seven decades spent in baseball’s front offices, Hemond helped to elevate three franchises to contenders while also cementing a reputation as one of the game’s great relationship builders. No matter where you were in Major League Baseball, it’s likely you or someone you knew were close with Roland Hemond.

But Hemond’s reputation stretched beyond his acumen for evaluating talent. He also served as president of the Association of Professional Baseball Players of America, which provides financial assistance and college scholarships to current and former players, scouts and others connected with pro baseball, and created the Professional Baseball Scouts Foundation. He was the first non-player to receive the Branch Rickey Award for community service, and was named the “King of Baseball” in 2001 for his contributions to the minor leagues.

As further testament to Hemond’s legacy, three other organizations – the White Sox, Baseball America magazine and the Society for American Baseball Research – named their service awards in honor of the legendary executive.

“He would give anyone an opportunity who loved the game and was willing to start at the bottom,” said former White Sox manager Chuck Tanner of Hemond. “He always had time for the little guy starting out, because he sold peanuts and popcorn himself.”

Matt Kelly is a freelance writer from Brooklyn, N.Y.