- Home

- Our Stories

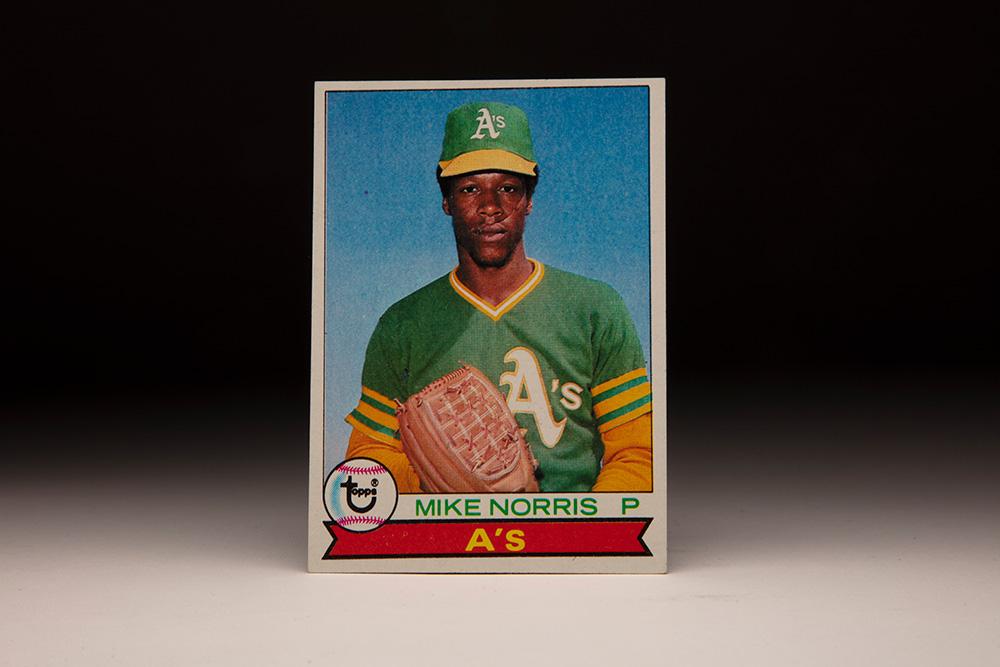

- #CardCorner: 1979 Topps Mike Norris

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Mike Norris

The April 27, 1981, cover of Sports Illustrated featured the starting rotation of the Oakland Athletics, a group that seemingly was going to put relief pitchers out of business.

After combining for an incredible 93 complete games in 1980, Rick Langford, Steve McCatty, Matt Keough, Brian Kingman and Mike Norris appeared poised to top that mark in ’81 – only to have overwork and a work stoppage derail their plans.

For Norris, it was the pinnacle of a career that saw him redeemed after substance abuse nearly took it all away.

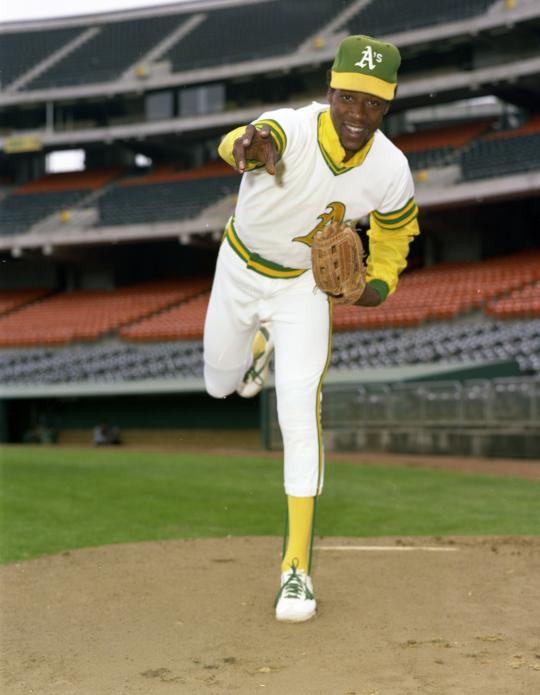

Born March 19, 1955, in San Francisco, Norris grew up in an impoverished area of the city but began receiving regional media acclaim in the early 1970s on the strength of his fastball. He went 6-1 with 62 strikeouts in 48 innings as senior at Balboa High School in 1972, also hitting .302 as center fielder while earning All-City honors.

The Athletics selected Norris – who graduated high school at 17 – in the first round of the January phase of the 1973 MLB Draft, signing him for a $45,000 bonus. The A’s assigned him to Class A Burlington of the Midwest League, where he was 8-4 with a 2.21 ERA, striking out 130 batters in 110 innings.

In 1974, Norris pitched for Birmingham of the Double-A Southern Association, going 7-8 with a 4.05 ERA in 109 innings. Then in 1975, the A’s invited Norris to Spring Training on Jan. 28 – a late move necessitated by Catfish Hunter’s defection to the New York Yankees. Hunter had been declared a free agent following the 1974 season after a contractual breach by Finley.

The A’s had little expectation that Norris would make the big league team, but after allowing just two runs over 16.2 innings he not only made the roster but was even inserted into the starting rotation. On April 1, he shut out the Milwaukee Brewers on one hit over five innings, getting Hank Aaron on a called third strike.

“When I (got) him out, it was like I had accomplished the impossible,” Norris told the Associated Press.

Norris made his regular season debut with the Athletics at the age of 20 on April 10, 1975, shutting down the White Sox on just three hits over nine innings in a 9-0 Oakland win.

“I’ve found my Jeremiah,” the Associated Press reported A’s manager Alvin Dark saying to team owner Charlie Finley following the game, a Biblical reference about finding unknown strength.

Norris appeared more than ready for the challenge of starting for the three-time defending World Series champions when he allowed just two unearned runs against the Royals in his second start on April 15. But in his third start, Norris threw only 11 pitches before leaving the game with a sore right elbow.

Ten days later, Norris had surgery to remove bone chips from his elbow and appeared in only one game the rest of the season, working two-thirds of an inning in relief on Sept. 25.

Norris returned to the mound in the A’s fourth game of 1976, working five innings as a reliever and allowing the first earned run of his career.

“We just don’t want to rush Norris,” new Oakland manager Chuck Tanner told the Associated Press. “But we’ll find a starting spot for him over the long haul.”

Norris returned to the rotation in late April but was largely ineffective and was sent to Triple-A Tucson in late May with an 0-2 record and 6.66 ERA. He returned to Oakland in June and spent the next two months in the rotation, recording a three-hit shutout over the Royals on July 4 but never recapturing the promise of 1975. He finished the season with a 4-5 record and 4.78 ERA over 96 innings with more walks (56) than strikeouts (44).

Norris proclaimed himself fit for the 1977 season – a year that began with many new faces in Oakland as owner Charlie Finley, in the face of the new free agent market, began dismantling his championship team.

“I didn’t even think about my (1975) operation last season,” Norris told the Independent of Richmond, Calif. “In fact, I think they tried to baby me too much.”

But Norris struggled again and was sent back to Triple-A in May. He returned in June with a four-hit shutout against the Mariners. Counting three consecutive complete games with Triple-A San Jose over a 10-day period, Norris was working at a volume he had never approached in previous seasons.

“I hope to turn into a pitcher instead of being just a thrower,” Norris told AP.

The Athletics, however, did not think Norris was making the transition fast enough and sent him back to San Jose in August. He finished the 1977 season with a 2-7 record and 4.77 ERA in 77.1 innings.

In 1978, Norris took a 20 percent pay cut when he lost in arbitration and failed to make the Opening Day roster for the first time since 1974 as the A’s sent him to Triple-A Vancouver to start the season. Norris said the A’s promised to bring him back to the big leagues after four starts but did not – and after a disastrous fifth start Norris was demoted to Double-A Jersey City of the Eastern League.

“It bummed me out,” Norris told the Hartford Courant of the demotion. “I decided in order to make something happen, to find something out, I wouldn’t report I got a call the next morning at 9 o’clock from (manager John) Kennedy telling me I was suspended without pay for one week.

“If I ever have children, maybe I can pass along the lessons of this experience to them. I look at myself realistically and know that I’m not yet fully mature. I still do dumb things. My trouble has always been that I’m impatient.”

After 16 starts in the minors, Norris returned to Oakland in July and worked mostly in relief the rest of the year, going 0-5 with a 5.51 ERA.

Now out of minor league options, Norris pitched the entire 1979 season with Oakland – going 5-8 with a 4.80 ERA in 146.1 innings as he shuffled between the rotation and the bullpen. The A’s lost 108 games that season, and prior to the 1980 campaign Finley hired Billy Martin as his new manager.

“To tell you the truth, I felt he’d be a hard-nosed guy,” Norris told The New York Times. “But the man has sincerity.”

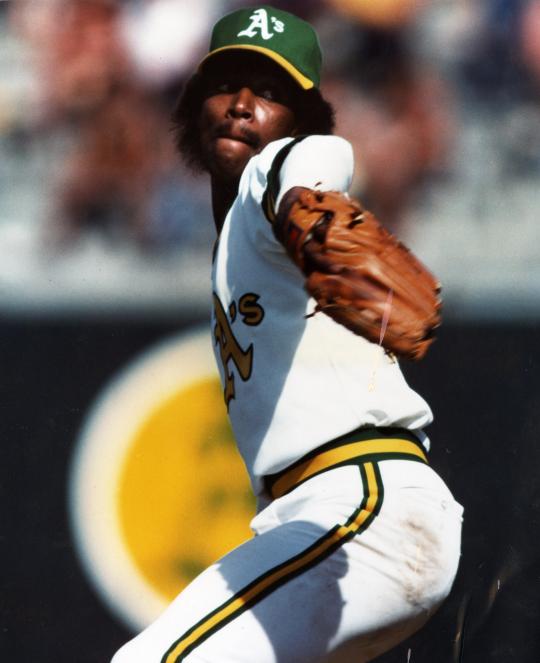

Martin quickly injected a new energy into the Athletics and also established a five-man rotation that had little need for the bullpen. Norris started the fourth game of the year and allowed just one unearned run over nine innings, striking out 11 in a 4-1 win over Minnesota.

On June 11, Norris began a streak of 12 complete games over 13 starts, then won his 20th game of the season on Sept. 16 and was carrying a 2.26 ERA into the season’s final week before he allowed 10 runs over nine innings against the Brewers on Sept. 26.

“I’m just 25 years old and still getting stronger,” Norris told the Associated Press when he was 5-0 with a 0.36 ERA early in the 1980 season. “(But) I’ll never be able to throw as hard as I once did.”

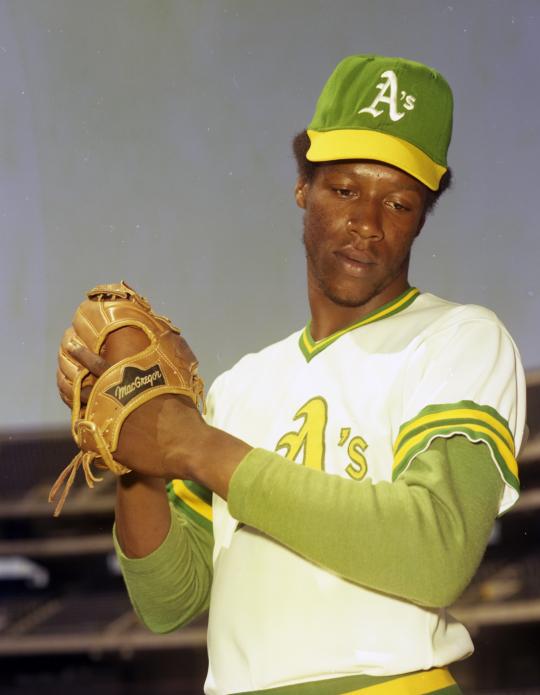

But Norris had something better than speed: A screwball, which he had toyed with in high school but now became his out pitch. He finished the season with a 22-9 record, 2.53 ERA and 180 strikeouts over 284.1 innings. He won the American League Gold Glove Award for pitchers and finished second in the AL Cy Young Award voting, tied with Baltimore’s Steve Stone with 13 first-place votes apiece but nine points behind Stone due to rankings in the second- and third-place spots on the ballot.

Stone led the majors with 25 wins that year, but Norris bettered him in virtually every other statistical category – posting a 5.9 WAR compared to 4.0 for Stone.

“Something is wrong with a whole lot of people,” Athletics pitching coach Art Fowler told the San Francisco Examiner prior to when the voting was announced, “if Mike Norris doesn’t get the Cy Young.”

Norris also failed to win his arbitration hearing in 1981, settling for $300,000 instead of the $450,000 figure which he submitted. But that was still almost a 10-fold raise over the $34,000 he made in 1980. He later signed a contract worth a reported $4.3 million that would carry him through the 1985 season.

“I figured I’d just get rich or richer,” Norris told AP following the arbitrator’s decision.

Norris, who became the 10th African-American pitcher to win 20 games in one season, continued his outstanding work in 1981. He began the season 6-0 and was 8-3 with a 3.25 ERA when the strike interrupted the season. The A’s won the first-half title and finished at 64-45, the best record in the AL. Norris went 12-9 with a 3.75 ERA and started Game 1 of the ALDS vs. the Royals, tossing a four-hit shutout in Oakland’s 4-0 win over Kansas City.

The Athletics went on to sweep the series and faced the Yankees in the ALCS, where Norris again started Game 1. This time, he allowed three runs over 7.1 innings in a 3-1 loss. New York swept the series to advance to the Fall Classic.

But the heavy workload – and the arm-deadening screwball – began to take its toll on Norris in 1982. He started 28 games but completed just seven of them, down from 12 the year before. More alarmingly, Norris was 7-11 with a 4.76 ERA and only 83 strikeouts in 166.1 innings.

Then in 1983, Norris totaled his new BMW when he hit a telephone pole on the way to the ballpark for his first start of the season in the Athletics’ second game of the year. Incredibly, Norris pitched into the sixth inning that day, allowing just two hits and two runs in a 5-3 win over the Indians. He was 4-5 with a 3.29 ERA through May but lasted only two innings in a June 7 start against Toronto, leaving the game with a sore shoulder and numbness in his arm.

Norris faced just two batters June 17 against the White Sox – walking Rudy Law and allowing an RBI single to Carlton Fisk – before again leaving the game with shoulder stiffness. He would appear in only three big league games the rest of the year, going 4-5 with a 3.76 ERA over 16 starts.

It would be the last MLB games Norris would pitch in the 1980s.

Norris had surgery in November of 1983 to repair his shoulder but was not invited to Spring Training in 1984. Then in May of that year, Norris was arrested at a motel on drug possession charges.

“I’m shocked, of course,” Athletics manager Steve Boros told AP. “You’d like to think that your players are not involved (in drugs). I guess that’s naïve.”

Norris tried to work his way back through the minor leagues but appeared in a total of only 13 games in 1985 and 1986 at the Class A level, drawing a fine and a one-week suspension in 1986 for missing a game with the San Jose Bees – a team that featured several players who had struggled with addiction. But after sitting out all of 1987, Norris got clean and began to work toward a comeback.

In 1989, he earned an invitation to Spring Training with the Athletics. He spent that season in Double-A and Triple-A, going a combined 7-6 with a 2.99 ERA at the age of 34. His substance abuse problems became a cautionary tale that even Norris tired of telling.

“I’ve talked about my addiction enough before,” Norris told the Albuquerque Journal in 1989 when he was pitching for Triple-A Tacoma of the Pacific Coast League. “If I choose not to talk about my recovery anymore, then let it stand.”

In 1990, Norris – at the age of 35 – completed his comeback when he made the Athletics’ Opening Day roster as a reliever.

“He realizes he has another opportunity, one that he thought would never come,” Ed Nevius, Norris’ high school coach who helped him train for his comeback with the A’s, told the San Francisco Examiner in the winter of 1990.

When Norris worked two scoreless innings for the A’s in the team’s third game of the season in 1990, it had been 2,439 days since Norris pitched in a big league game. He pitched in 14 games for the A’s that year, posting a 3.00 ERA over 27 innings before being released in July.

“I’m very much shocked and surprised, but that’s baseball,” Norris told AP. “I’m pretty sure the Lord has a plan for me.”

Norris pitched for the Class A Reno Silver Sox in 1991, working effectively before a pulled hamstring limited his opportunities. He finished that season 0-3 in six games and did not pitch again in organized baseball.

Norris finished his 10-year big league career with a 58-59 record and a 3.89 ERA. He recorded at least one complete game in each of his first nine seasons, and he is the only pitcher in the Divisional Play Era (1969 to present) with at least 50 complete games and fewer than 125 decisions.

But as durable as Mike Norris was on the mound, he was tougher in his battle with addiction.

“There are three things you can look forward to with cocaine: Hospitalization, incarceration and death,” Norris told the Los Angeles Times in 1990. “I’d done two of the three. The only thing left was death. It was the next step.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum