- Home

- Our Stories

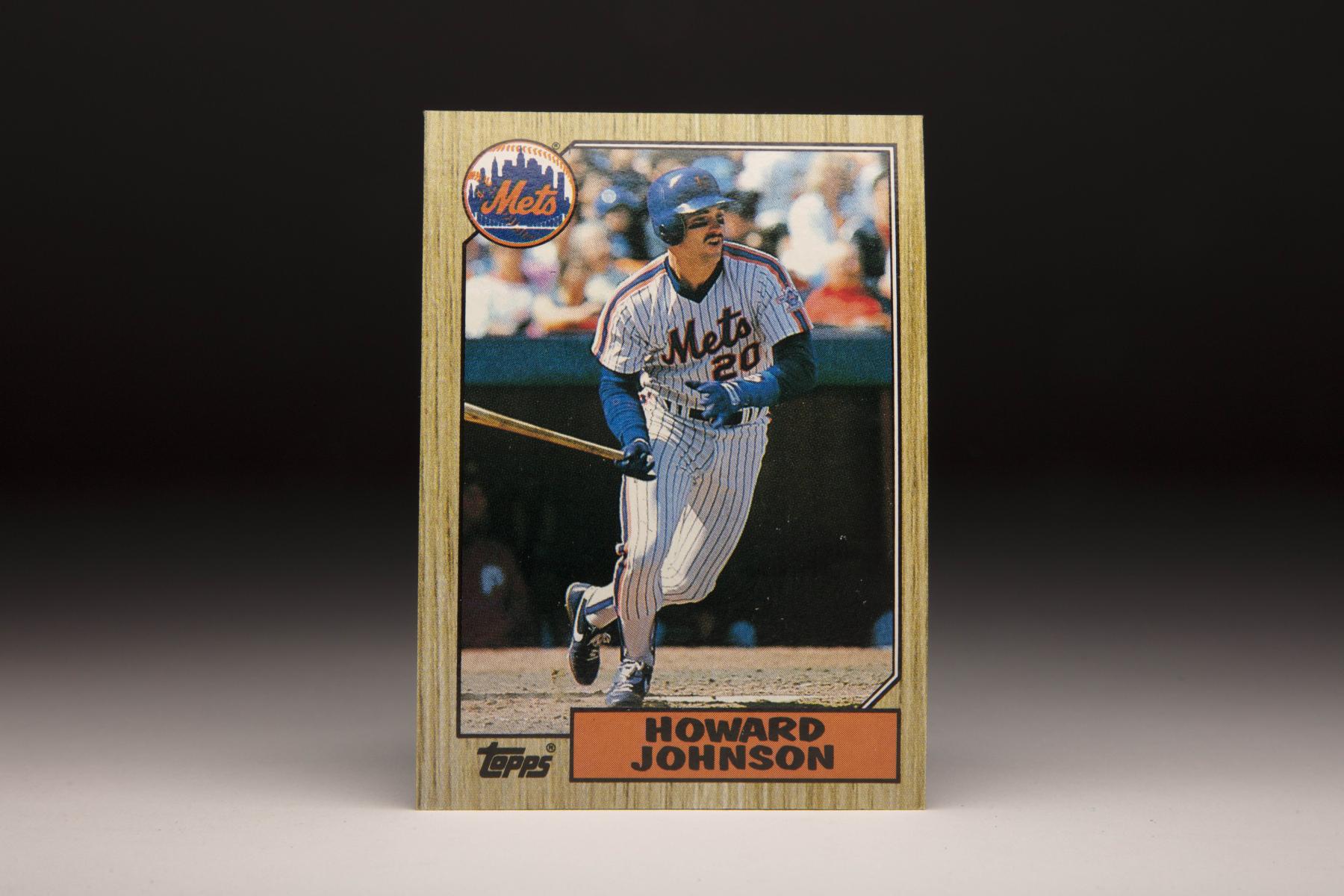

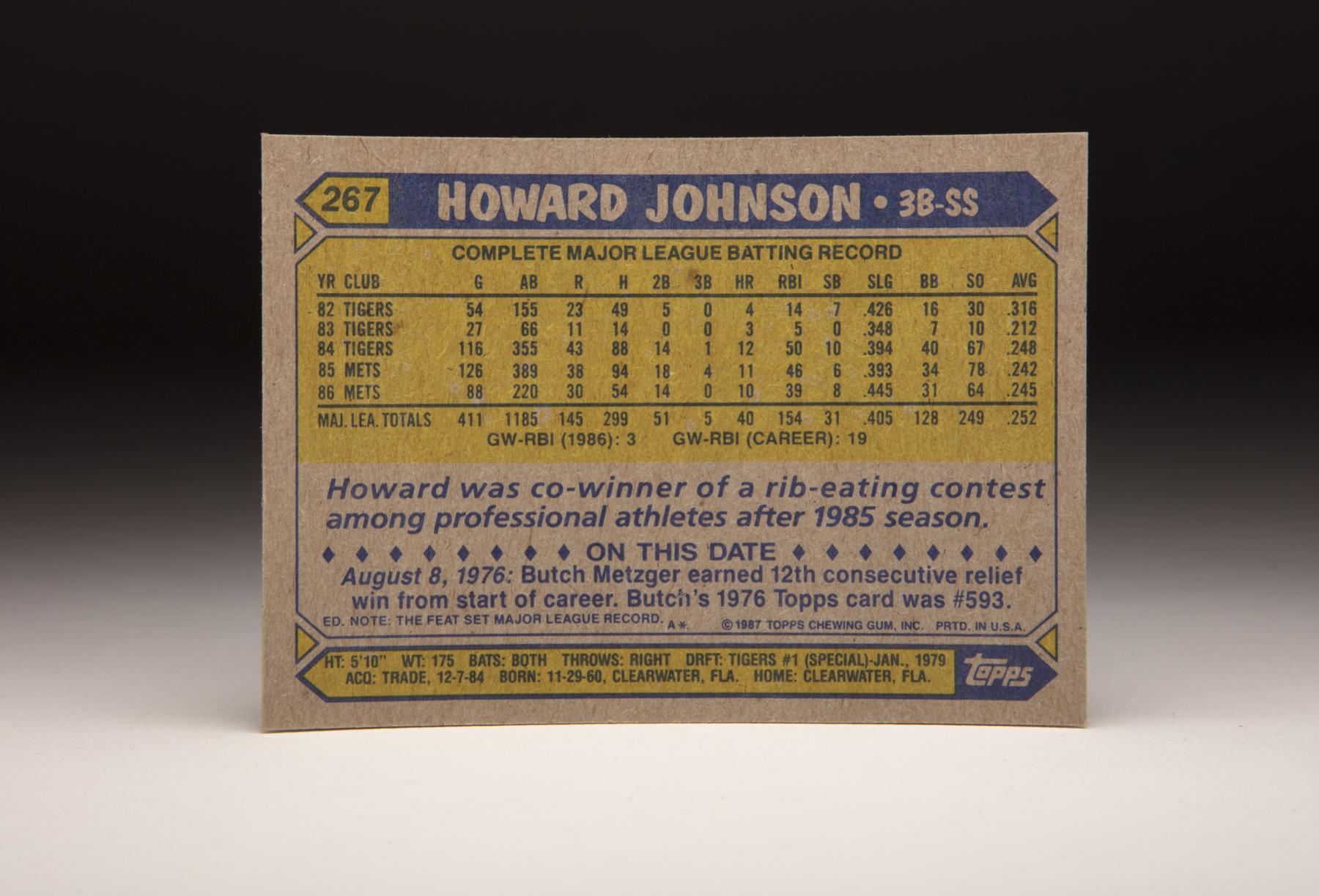

- #CardCorner: 1987 Topps Howard Johnson

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Howard Johnson

In an era where a power/speed combination was viewed as the best example of all-around baseball talent, Howard Johnson became just the seventh player in baseball history to post a 30 homer/30 steal season.

Two years later, he repeated the feat – narrowly missing out on achieving the first 40/40 campaign in National League history.

In a 14-year big league career that featured two World Series titles and plenty of national buzz, Johnson – for a time – was recognized as one of baseball’s best.

Born Nov. 29, 1960, in Clearwater, Fla., Johnson was the oldest of three children of Bill and Sue Johnson. His father coached him in youth ball, teaching Howard how to switch-hit at an early age.

“He was only three years old when he started switch-hitting with a tiny bat and ball in the backyard,” Bill Johnson told the Tampa Tribune. “Then when he got to breaking our windows, we went to Belleair Elementary. When that got too small, we moved down to the Little League park. He was only five or six years old and we needed the fences.”

With his father pushing him, Johnson began appearing on youth all-star teams with players who were one or two years older than him.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

“I think he realized that baseball was what I wanted to do,” Johnson told the Tampa Tribune. “I think for our own good, he was strict in that he didn’t let us have the freedom to pick and choose whether we wanted to play or not. The works habits that I have now were formed by my dad. When you get to a certain level of baseball, things your father teaches you are really no longer of any use. But it’s the attitude – the things you think about when you have decisions to make – those are the lasting things parents teach their kids.”

Playing year-round in the Florida sunshine, Johnson evolved into a star for Clearwater High School, hitting .375 as a junior. But he seemed to be headed for a career on the mound, and as a senior Johnson hit just .275 but had an 0.91 ERA and 110 strikeouts in 91 innings.

The Yankees selected Johnson in the 23rd round of the 1978 MLB Draft, but Johnson instead enrolled at St. Petersburg College. In January of 1979, the Tigers took Johnson in the first round of that draft, which was specifically set up for college players.

The Tigers sent Johnson, still only 18 years old, to Class A Lakeland of the Florida State League in 1979. He batted .235 with 49 RBI and 18 stolen bases in 132 games, holding his own against players who were on average about three years older than he was.

Johnson was sent back to Lakeland in 1980, and this time he hit .285 with 10 homers, 69 RBI and 31 stolen bases while being named a FSL All-Star. That performance earned him a promotion to Double-A Birmingham in 1981, and Johnson starred in the Southern League – hitting .266 with 22 homers, 83 RBI and 19 steals after a slow start that saw him leading the team in strikeouts and errors in mid-May. But after hitting homers from both sides of the plate in a May 20th game against Chattanooga, HoJo – as he was called even then – found his grove.

The Tigers brought Johnson to their Spring Training camp in 1982 with the full expectation that he would spend that season with Triple-A Evansville. When Detroit manager Sparky Anderson sent him down to the minors on March 22, the move came with a promise for the future.

“I told him this morning that it will be nobody’s fault but his if he isn’t playing in the major leagues next year,” Anderson told the Tampa Bay Times. “He can hit, field and run – and Howard has a great attitude. He has everything a player needs to play this game.”

But within a month of being sent to Triple-A, Johnson was in the big leagues. Recalled after playing in just one game in Evansville due to injuries to Rick Leach and Eddie Miller, Johnson debuted for Detroit on April 14 – batting leadoff and starting in right field against the Blue Jays. He was 1-for-4 with a run scored, playing regularly at third base over the next three weeks before being returned to Evansville in May.

“I am so high on Howard Johnson, it is unreal,” Anderson told the Evansville Press. “If he ain’t ready, who is ready? I’ll tell you this, that Johnson is the third baseman of Detroit’s total future – and it could be sooner than that.”

But with veteran Tom Brookens – an Anderson favorite – in the lineup, the Tigers could afford to bring Johnson along slowly. He blistered Triple-A pitching to the tune of a .317 batting average with 23 homers, 67 RBI and 35 stolen bases in 98 games that summer before returning to Detroit in August, where he saw action in the outfield and at third base for the rest of the year – finishing with a .316 batting average and 23 runs scored in 54 games.

Johnson worked hard on his fielding in Spring Training of 1983 – and improved significantly when he switched gloves to a smaller model more fit for an infielder. But Anderson kept the right-hand hitting Brookens in the lineup by platooning him with Johnson, and Johnson was hitting just .212 in late May when he was sent back to Triple-A.

He appeared in just three games with Evansville before suffering a broken right index finger on June 2, then re-broke the digit three weeks later during infield practice. The second injury necessitated surgery that sidelined Johnson for the rest of the 1983 season.

Brookens and Johnson again split time in 1984, a situation complicated by the presence of prospect Barbaro Garbey, who also saw time at third base. But the Tigers put aside any issues with a record-setting 35-5 start to the season – and Johnson pushed his batting average to as high as .337 in mid-June. But he finished the year hitting .248 with 12 homers and 50 RBI in 116 games and had apparently fallen out of favor with Anderson, who played him in only one of Detroit’s eight postseason games – a pinch-hitting appearance in the final game of the World Series – as the Tigers won the world championship.

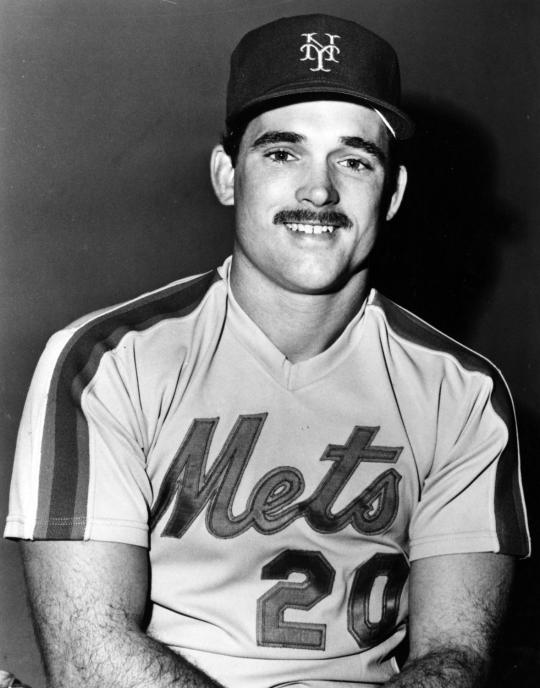

During the World Series, Anderson predicted that Johnson would be his starting third baseman in 1985. But on Dec. 7, 1984, Johnson was traded to the Mets in a one-for-one swap for pitcher Walt Terrell.

“At 24, Johnson has yet to touch the tip of his athletic abilities,” Mets general manager Frank Cashen told the Associated Press following the trade. “He will add a new dimension to our attack.”

But the Mets already had a third baseman, Ray Knight, who was coming off arm surgery but was acquired for three prospects late in the 1984 season and was expected to play in 1985.

Johnson began the 1985 season as the Mets’ Opening Day third baseman, with Knight still recovering from his injury. Johnson, however, starting the season slowly as he adjusted to the National League and was hitting .194 with two homers and 11 RBI in 58 games when he woke up on the Fourth of July. From that point, however, Johnson hit .277 with nine homers and 35 RBI to finish the year on an upswing.

In 1986, the Mets put together a season much like the 1984 Tigers – rolling through the competition on the way to a World Series title. And just like in 1984, Johnson was often on the outside looking in at his team’s success. He started at third base on Opening Day but was moved to shortstop near the end of April after Knight caught fire with 12 RBI in his first nine games.

Then on June 1, Johnson and Lenny Dykstra collided while chasing a pop fly against the Giants at Shea Stadium. Johnson injured his right forearm on the play, sidelining him for three weeks. He alternated starts with bench roles the rest of the year, finishing with a .245 batting average, 10 homers and 39 RBI in 88 games. He was relegated to mostly pinch-hitting duty in the postseason, starting only Game 2 of the World Series vs. the Red Sox and going 0-for-7 overall.

Johnson would have had no way of knowing it, but his ascent to superstardom was right around the corner.

Knight left the Mets via free agency following the 1986 season, and Johnson stepped at third base, fending off a challenge from young Dave Magadan. After holding his own for the first three months of the season, Johnson had a torrid July – hitting 10 home runs and stealing seven bases to give him 25 homers and 20 steals heading into August.

Around that time, Johnson was accused of corking his bat by multiple managers, including the Cardinals’ Whitey Herzog. Johnson was cleared of all charges – and his breakout season seemed to be explained simply by the maturation of his immense physical tools.

“All this talk about my using a corked bat is silly and kind of insulting,” Johnson told Knight-Ridder Newspapers. “Let them say what they want; I don’t listen anymore. Pretty soon they’ll forget all about the cork stuff, but they’ll remember me.”

Johnson’s 1987 season would have fans talking about him for years to come. He broke the NL home run record for switch hitters, which was set in 1934 by the Cardinals’ Ripper Collins (35), finishing the season with 36 homers, 99 RBI, 93 runs scored, 32 steals and a .265 batting average while finishing 10th in the NL MVP voting. Prior to Johnson – who joined the 30/30 club on Sept. 11, just five days before Cleveland’s Joe Carter became the eighth player to hit that mark – only Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Bobby Bonds and Dale Murphy had posted 30/30 seasons in the National League.

Johnson again started the season slowly in 1988 and never really recovered, finishing the year with a .230 batting average 24 home runs, 68 RBI and 23 steals. A change of positions likely did not help, as Johnson was moved to shortstop to make room for prospect Gregg Jeffries.

The Mets won the NL East and Johnson started at shortstop in four of the seven games of the NLCS vs. the Dodgers, going 1-for-18 as New York lost to Los Angeles. It would be the final postseason appearance of Johnson’s career.

In February of 1989, reports surfaced that Johnson would be traded to the Mariners along with Sid Fernandez and David West in a blockbuster deal that would have brought Mark Langston and Jay Buhner to New York. But it turned out to be just one of many rumored deals involving Johnson that were never consummated.

Johnson had arthroscopic surgery on his right shoulder following the 1988 season, and in 1989 was once again the Mets’ Opening Day third baseman. This time, he got out of the box quickly – hitting better than .300 well into May while displaying the 1987 versions of his power and speed. He finished the season with an NL-best 104 runs scored, 36 homers, 101 RBI, 41 doubles and 41 steals – missing out by only four homers on becoming the second 40 homer/40 steal player in baseball history.

Following his appearance in the All-Star Game – where he started at third base for the National League – Johnson signed a three-year extension worth a reported $6.2 million.

Johnson’s numbers regressed a bit in 1990 as he hit .244 with 23 homers, 90 RBI and 34 steals. But he bounced back in 1991, leading the NL with 38 homers and 117 RBI while stealing 30 bases and scoring 108 runs.

Only Bobby Bonds – who had five 30/30 seasons from 1969-78 – had more 30/30 seasons than Johnson’s three to that point. To this day, only Bonds and his son Barry Bonds, both with five, along with Alfonso Soriano (4) have more 30/30 seasons than Johnson.

Johnson duplicated his 1989 awards season performance by winning a Silver Slugger and finishing fifth the MVP voting. But the 1991 Mets finished 77-84, leading to new manager Jeff Torborg taking over in 1992. He promptly moved Johnson to center field, clearing space for Magadan while asking Johnson to learn a new position. By July, Johnson was in left field – and he did not play a game after Aug. 1 due to a wrist injury. He finished the season hitting .223 with seven homers, 43 RBI and 22 steals.

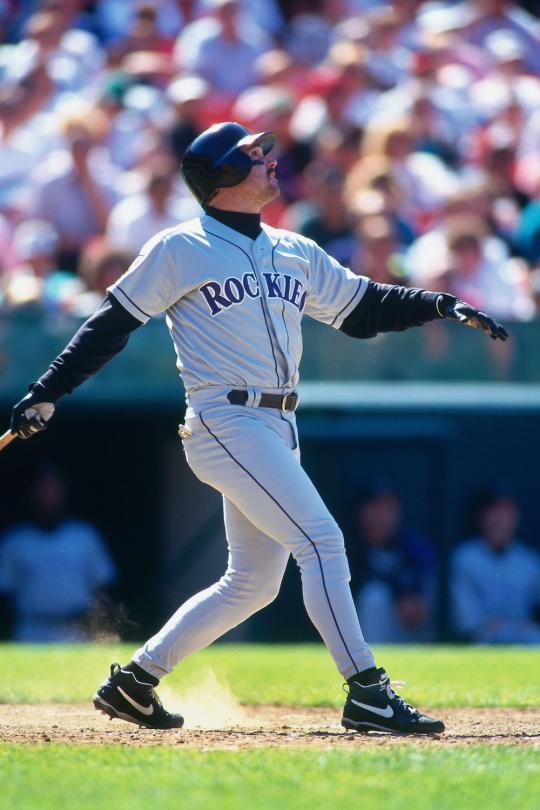

The Mets moved Johnson back to third base in 1993, but he contracted human parvovirus in June and did not play after July 22, appearing in just 72 games while hitting seven home runs to go with 26 RBI. With his contract now expired, Johnson agreed to a one-year, $2.1 million deal with the Colorado Rockies on Nov. 19, 1993.

But playing in the offensively-charged atmosphere in Denver did not revive Johnson’s career as he hit .211 in 93 games before the strike ended the season. He signed with the Cubs for 1995 but hit .195 in 87 games.

Finding no playing opportunities in 1996, he took a job as a coach with the Buttle Copper Kings of the Pioneer League, helping instruct players in the Devil Rays’ system two years before the big league franchise took the field. He returned to the Mets in Spring Training of 1997 with hopes of making the team but announced his retirement on March 26 when it became obvious he would not go north with the club.

“I really admire the guy,” Mets general manager Joe McIlvaine told the New York Daily News. “I think he feels relieved. I think he feels fulfilled.”

Johnson soon joined the Mets’ minor league organization and worked his way through the system, becoming the big league first base coach in 2007 – a position he held through the 2010 season. He would later serve as a coach for the Mariners.

In 14 seasons in the big leagues, Johnson hit .249 with 228 homers, 231 stolen bases and a .446 slugging percentage. His career included two All-Star Game selections, two World Series rings – and the label, for a time, as one of the best all-around offensive players in the game.

It was the fulfillment of a wish that began when he was a toddler in Tampa Bay.

“Playing in the big leagues is my goal,” Johnson told the Tampa Bay Times during his first big league Spring Training in 1982. “It has been my goal since I was a little kid.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum