- Home

- Our Stories

- After Pearl Harbor, baseball played a part in fight for freedom

After Pearl Harbor, baseball played a part in fight for freedom

When the calendar pages in the westernmost points of Alaska’s distant islands turned from Saturday, Dec. 6, 1941, to Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, the United States were a completely different place than where they would be 24 and 48 hours later.

Baseball was no different.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

On Dec. 7, 1941, the Detroit Free Press reported that Tigers slugger Hank Greenberg was awaiting his 1942 contract after receiving his honorable discharge from the Army two days earlier. Greenberg missed most of the 1941 season while serving in the military.

“For the next few days I hope to forget about baseball, the Army and everything else and concentrate on re-acclimating myself to civilian life,” Greenberg said.

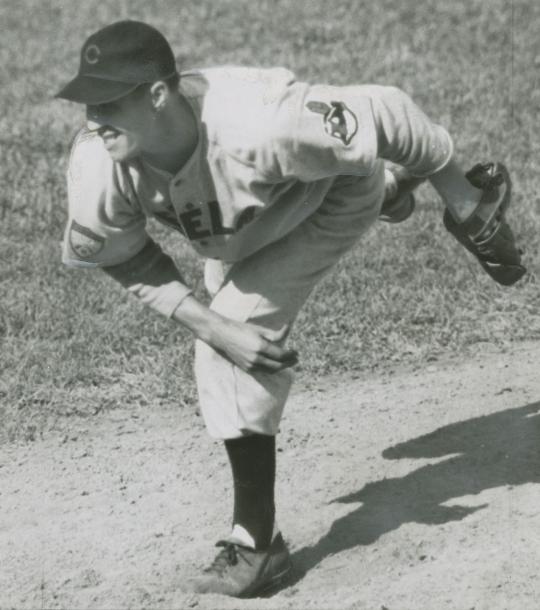

The Associated Press reported on Dec. 6, 1941 that Cleveland ace Bob Feller would choose to enlist in either the Army or the Navy rather than wait for the draft.

“I’ve always been ready to go, but I’ve been busy trying to decide what to join,” Feller told the AP on Dec. 6. “I haven’t definitely decided yet but I’ll make up my mind by Monday.”

Feller’s friends suggested he might be able to take the mound for Cleveland on his days off, which Feller thought was “not a bad idea. I’ll sure look into it.”

The Honolulu Advertiser headline on Dec. 7, 1941, said, “F.D.R. Will Send Message to Emperor on War Crisis.”

Not long after the newspaper hit newsstands that morning, it was Emperor Hirohito and the Japanese Imperial Navy who would send the message.

The Japanese altered the fates of Greenberg and Feller – and millions of other Americans, ballplayers and non-ballplayers alike – when the Imperial Navy’s Air Service began pelting the Pearl Harbor Naval Station and nearby American military installations in Hawaii. The attacks, which occurred shortly before 8 a.m. local time Sunday morning (1 p.m. on the United States’ east coast), officially thrust the United States into World War II.

Before a joint session of Congress on Dec. 8, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared that Dec. 7 would be “a date which will live in infamy,” as he sought a formal declaration of war against the Empire of Japan.

In two waves of bombardment, hardest hit by the Japanese were the Pacific Fleet’s battleships, mostly moored off Ford Island, as well as American aircraft stationed throughout the area. More than 2,300 Americans lost their lives, nearly half of which occurred as the battleship Arizona, hit by armor-penetrating shells, exploded and sunk into the harbor.

The only known former professional baseball player to have been killed in the attacks was Jerry Angelich, a pitcher who spent some time on the pre-season roster of the Pacific Coast League’s Sacramento squad in the mid-1930s. Angelich was stationed at nearby Hickam Field with the US Army Air Corps’ Headquarters Squadron, 17th Airbase Group. While trying to use a machine gun from a wrecked plane, he was killed by gunfire from Japanese fighter pilots.

Peacetime – and the simple joys of playing baseball – never seemed so far away.

Baseball – and sports, in general – had been a regular part of life for servicemen in Hawaii prior to the attacks on Pearl Harbor. Team sports in particular had long been considered effective in developing young military officers, the Chicago Daily Tribune’s Walter Trohan wrote.

“The excellence of the crop of officers has been attributed by military students to the American way of life,” he noted. “Football, baseball, and other sports which teach cooperative effort, discipline, and quick use of judgment aided young men to step into posts of command.”

In a letter, which was read at the annual dinner of the New York chapter of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America in Feb. 1941, President Roosevelt remarked on the importance of recreation and baseball to the morale of the American people.

“The country is witnessing an unprecedented expansion in its armed forces on land, on sea and in the air,” the President wrote. “And in the building up of morale – whether in the armed forces or in the civilian population – we all know the part that recreation always has played and of necessity must continue to play. That is where baseball comes into its own.”

Evidence of baseball building such morale in and around the Pearl Harbor military bases could be found throughout Hawaiian newspapers of the period.

Practically every unit and ship fielded a squad, and sailors, soldiers, airmen, and Marines were all keen to attend games or follow the latest results. Newspapers in Honolulu regularly reported on the goings-on, often providing colorful commentary.

There were also traditions to be had, one especially being the CPO baseball trophy. In May 1936, teams of chief petty officers from the battleship Nevada and the repair ship Vestal squared off, with the Nevada winning 7-5.

“A pitcher used on that memorable day for serving liquid refreshments became a symbol. … This pitcher has now developed into a large and handsome trophy, which any ship would be proud to possess. It has been competed for approximately 96 times by 38 different ships during its five years of existence,” according to the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, which also said that the ship possessing the trophy is deemed to have “the champion CPO baseball team in the fleet.”

In 1941, the Nevada placed a challenge against the battleship Oklahoma’s possession of the trophy. The Oklahoma had just turned back the Arizona to retain the trophy. On June 8, 1941, the Nevada recaptured the pitcher. When the trophy returned to the Nevada’s CPO mess, the Star-Bulletin described that “one could not help but notice the look in the eyes of some of the old timers who were on the ship when the trophy first took existence. It must have brought back to them pleasant memories and cheerful recollections of the Nevada five years ago.”

On Nov. 28, 1941, merely nine days prior to the attacks, The Honolulu Advertiser reported on the baseball team from Submarine Squadron Four defeating the battleship U.S.S. Oklahoma’s squad, 6-5, to capture the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s championship.

“Using their bats like so many torpedoes … [i]t took them just eight innings to defeat the battlewagon aggregation,” the Advertiser said. The Oklahoma, champions among the battleship teams, held a 5-3 lead into the seventh but succumbed to a submariner rally.

For Submarine Squadron Four, it was the second big win of the day. Earlier that day, they beat the U.S.S. Northampton, champions of the cruisers, 9-5, to reach the fleet finals.

Just over a week later, the submarines and the Northampton would escape damage during the attacks on Pearl Harbor.

The Oklahoma was not as lucky. Hit by five Japanese torpedoes, the ship capsized and was deemed a total loss. Over 400 sailors perished. It appears, however, that the nine men in the ship’s starting lineup for the Pacific Fleet championship may have all survived the attack.

The Nevada managed to steam away during the attacks but was still hit by several bombs before it was grounded in shallower water. It returned to service less than a year later.

Though unaffected by the attacks on Pearl Harbor, the Northampton would be lost nearly a year later at the Battle of Tassafaronga, near Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands.

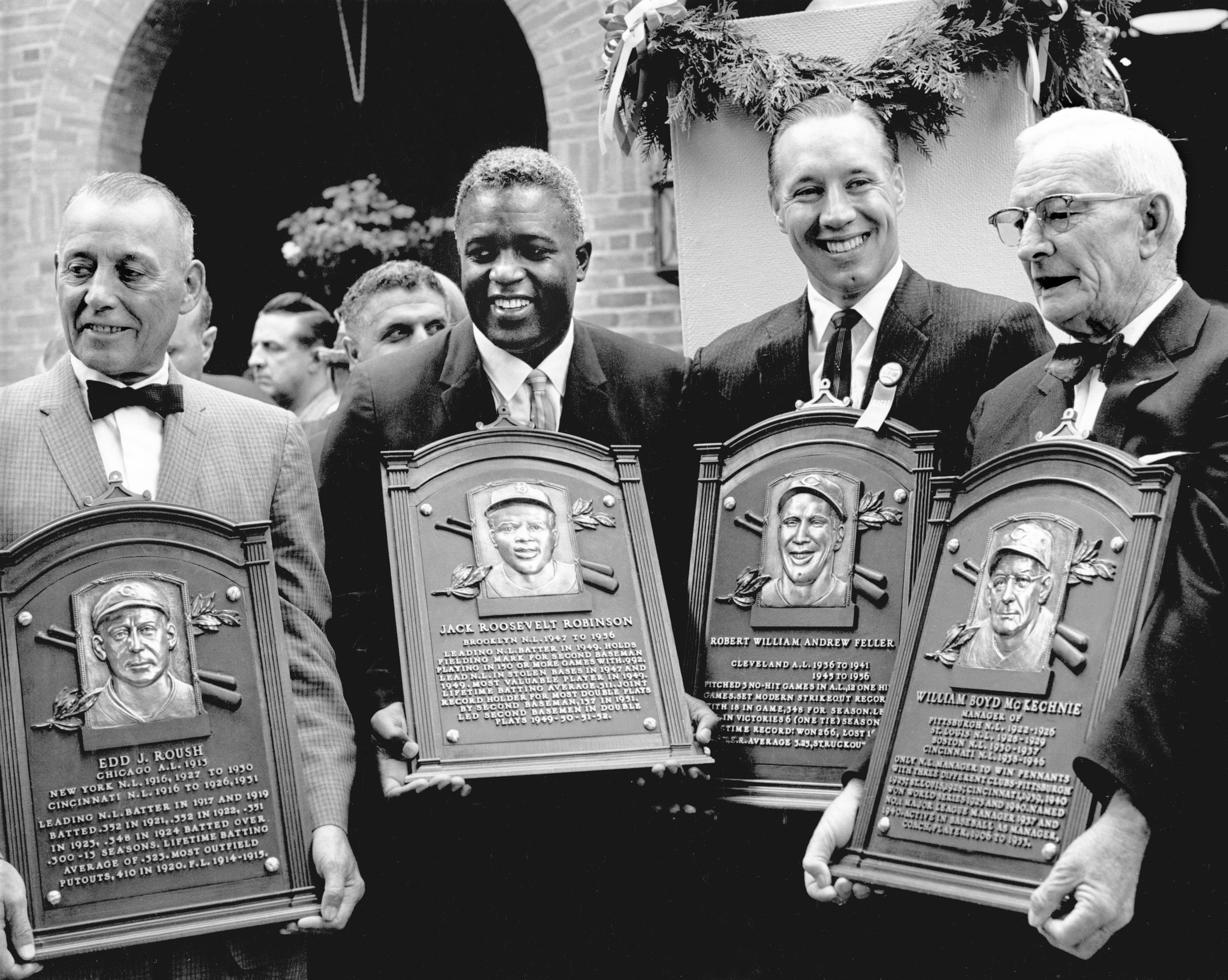

President Franklin Roosevelt throws out the first pitch on Opening Day 1937, at Griffith Stadium in Washington D.C. To his left is Hall of Famer Clark Griffith, the owner of the Washington Senators, and to his right are fellow Hall of Famers Connie Mack, and Bucky Harris. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Bob Feller decided on Dec 10, 1941, that Navy life would suit him best and enlisted, answering the call “to help out where I can be of most service to my country.” He told sportswriters that “[n]obody knows what’s going to happen. Maybe I’ll see you fellows again and maybe I won’t.”

Hank Greenberg, too, heeded the call to action. Just discharged, he decided to re-enter the Army. “I’m going back in,” he said. “We are in trouble and there is only one thing to do – return to the service.”

Millions of Americans – including hundreds of professional ballplayers – would follow suit and join the armed forces.

Baseball would continue to play a pivotal role in diversions from the battlefield.

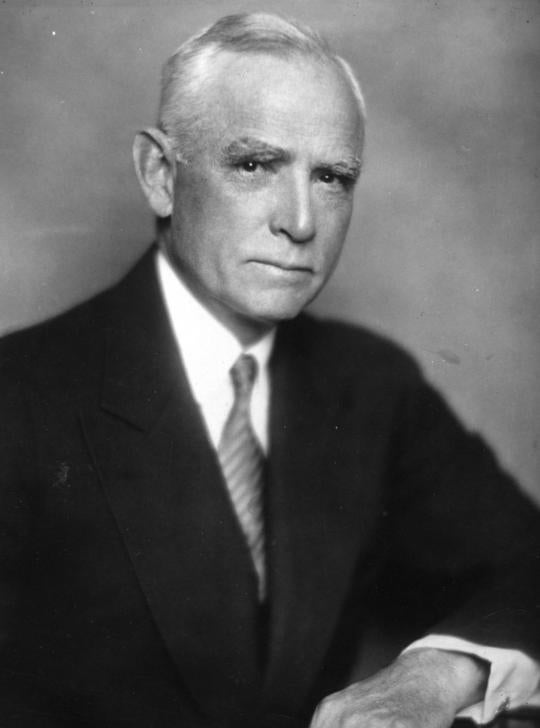

Later in Dec. 1941, Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith, National League President Ford Frick, Captain Frederick H. Weston of the Army’s Morale Division, and representatives of various sporting goods manufacturers met in Washington, D.C. The purpose was to determine how to best supply the military with baseball equipment in order to keep up the troops’ morale.

The sporting goods would be “the best we can get – none of that cheap stuff for the soldiers and sailors, only the best for them,” according to Griffith.

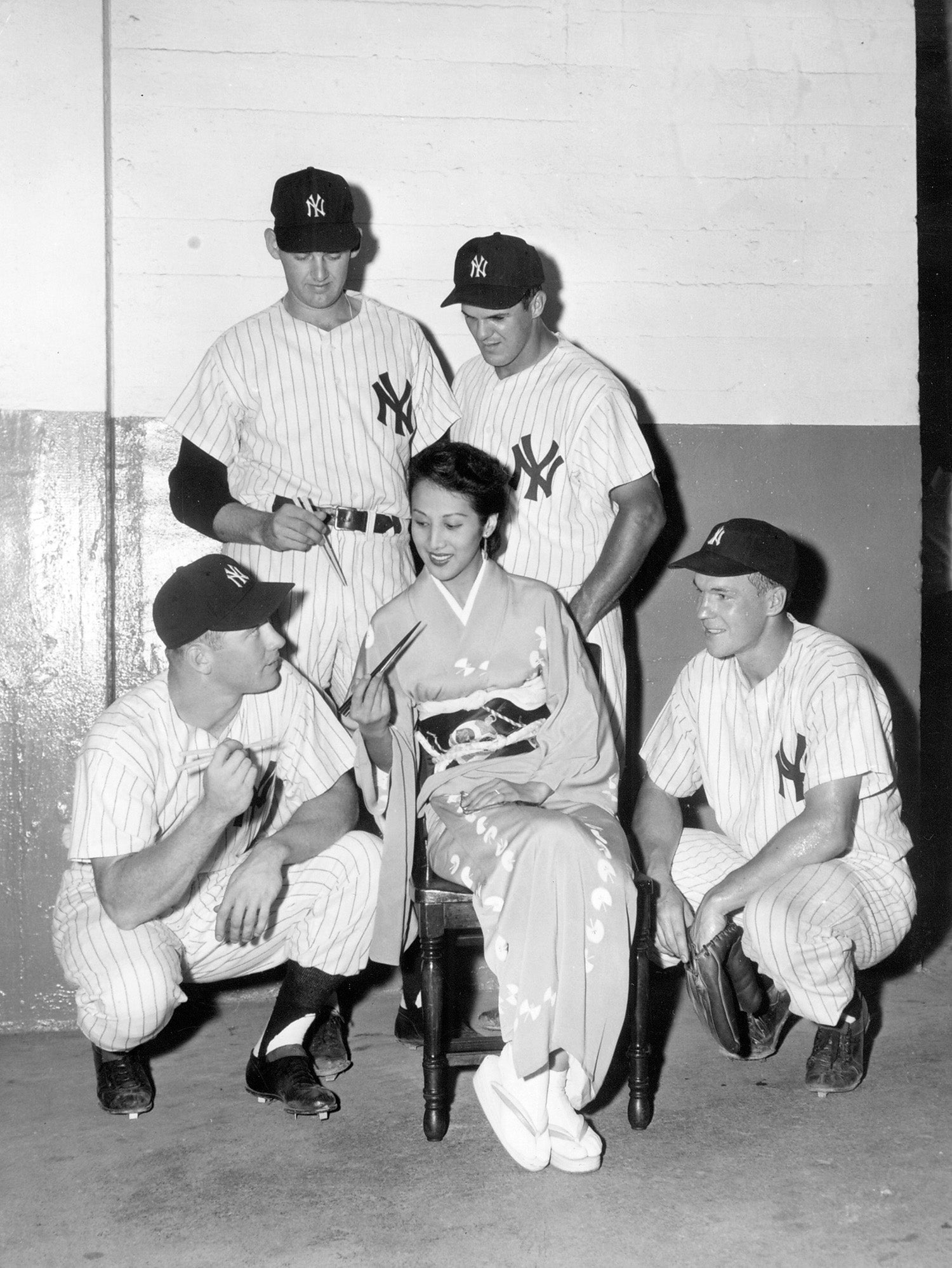

U.S. military baseball expanded past stateside bases and was soon being played in all corners of the globe.

The attacks on Pearl Harbor would rate as a watershed moment in American history, in world history, and in the lives of millions of people throughout the globe.

Though we may never know if Submarine Squadron Four would have retained its title as champions of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, we do know that its sailors’ next competition held much higher stakes – a must-win championship for the free world.

Matt Rothenberg is a freelance writer from Ossining, N.Y.