- Home

- Our Stories

- ALS and Baseball exhibit sheds more light on the story of Lou, Catfish and Pete

ALS and Baseball exhibit sheds more light on the story of Lou, Catfish and Pete

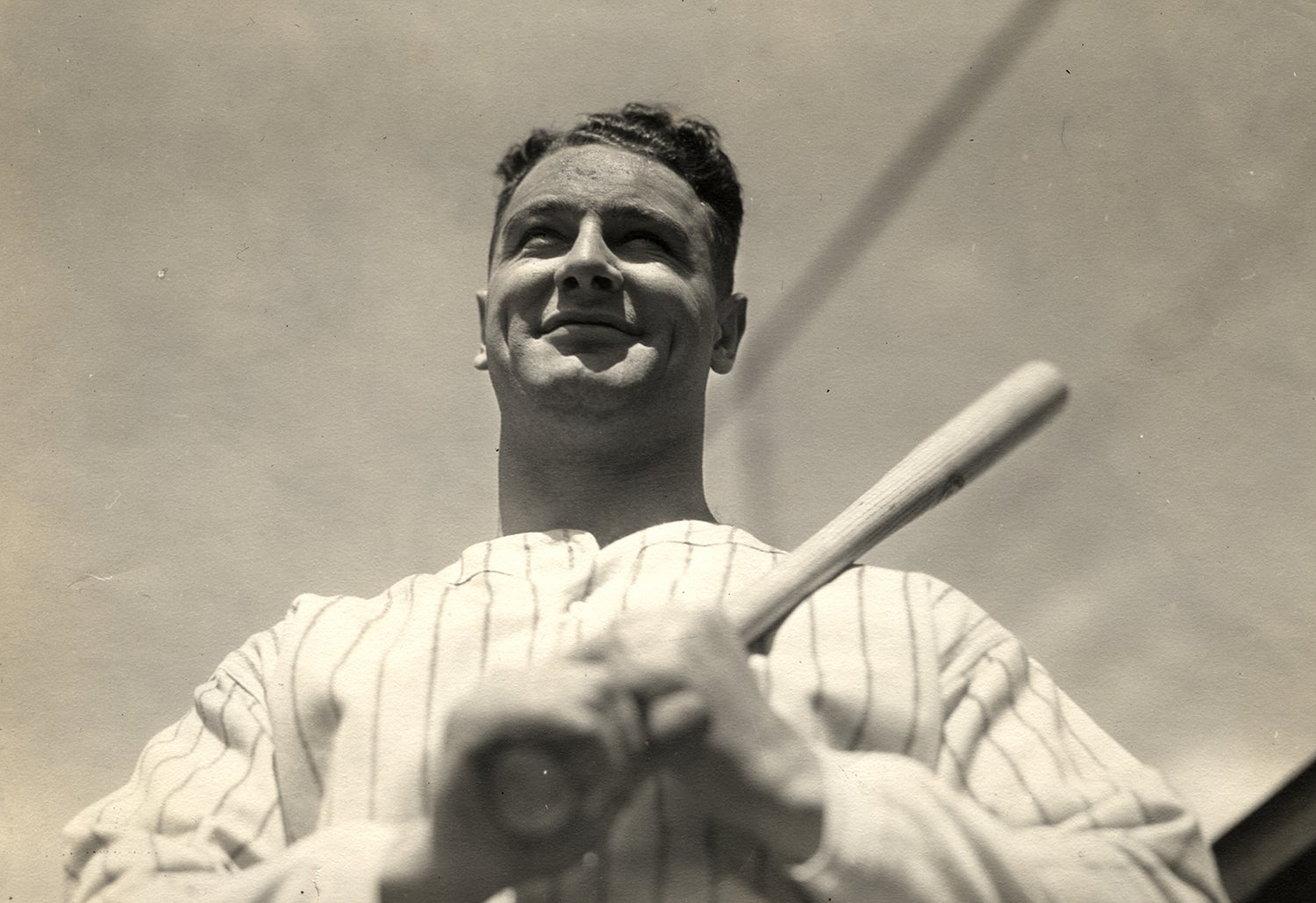

It’s one of the most iconic speeches in American history. On YouTube, the countless videos of Lou Gehrig’s farewell speech on July 4, 1939 have accumulated millions of views. And 78 years later, that moment has been replayed and analyzed every which way. But when Pete Frates watched Lou’s moment shortly after receiving his ALS diagnosis in 2012, he had a different take.

“He studied the Luckiest Man speech over and over again,” Pete’s father, John Frates, said. “He really showed us some profound moments in that speech. There was one in particular, where Gehrig, instead of accepting his trophy, had to guide it to the ground; he didn’t have the strength to hold it up.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“He identified with that so much,” continued Pete’s mother, Nancy. “He knew exactly what Lou Gehrig was feeling at that moment.”

It just so happens that Pete and Lou have a lot more in common than Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Left-handed sluggers who were multi-sport athletes, Lou and Pete were also the types of players who didn’t need the limelight to feel satisfied. They were perfectly content with hustling in the shadows of larger stars – as long as they were contributing to the team.

But then we come to a difference in generation.

“At the earlier part of the 20th century, men were dignified – they were not trying to expose any malady that they might be having,” said John. “But Pete in this modern era, he wanted to put himself out there, he wanted to be seen on social media, he wanted people to experience this journey with him.”

The last memory we have of Lou Gehrig is on July 4, 1939 in front of 61,000 fans at Yankee Stadium. He would succumb to the disease two years later, but we won’t see any videos, any photographs of Gehrig in treatment, or even of him in a remotely debilitated state. Which of course, isn’t the fault of the Yankee legend, more than a characteristic of the era he lived in.

Pete Frates, on the other hand, was presented with the ability to share his journey with the world – and has embraced the opportunity.

“When he was diagnosed the doctors told us, ‘Get his affairs in order, make him comfortable, to live his 2-5 years of life. That was the mindset of the medical community,” said John. “It was ‘Keep this quiet, you are going to lose all of your dignity, keep this under wraps.’ Well if it’s not exposed to the light, how do you raise awareness, how do you start this fundamental process of raising the necessary funds?”

“After Pete brought the disease into the modern world and drew awareness to it – with thousands of Ice Bucket Challenges and millions of dollars raised – we’re on the precipice of effective treatment and a cure,” he continued. “There’s no doubt that this new awareness campaign of social media is so powerful.”

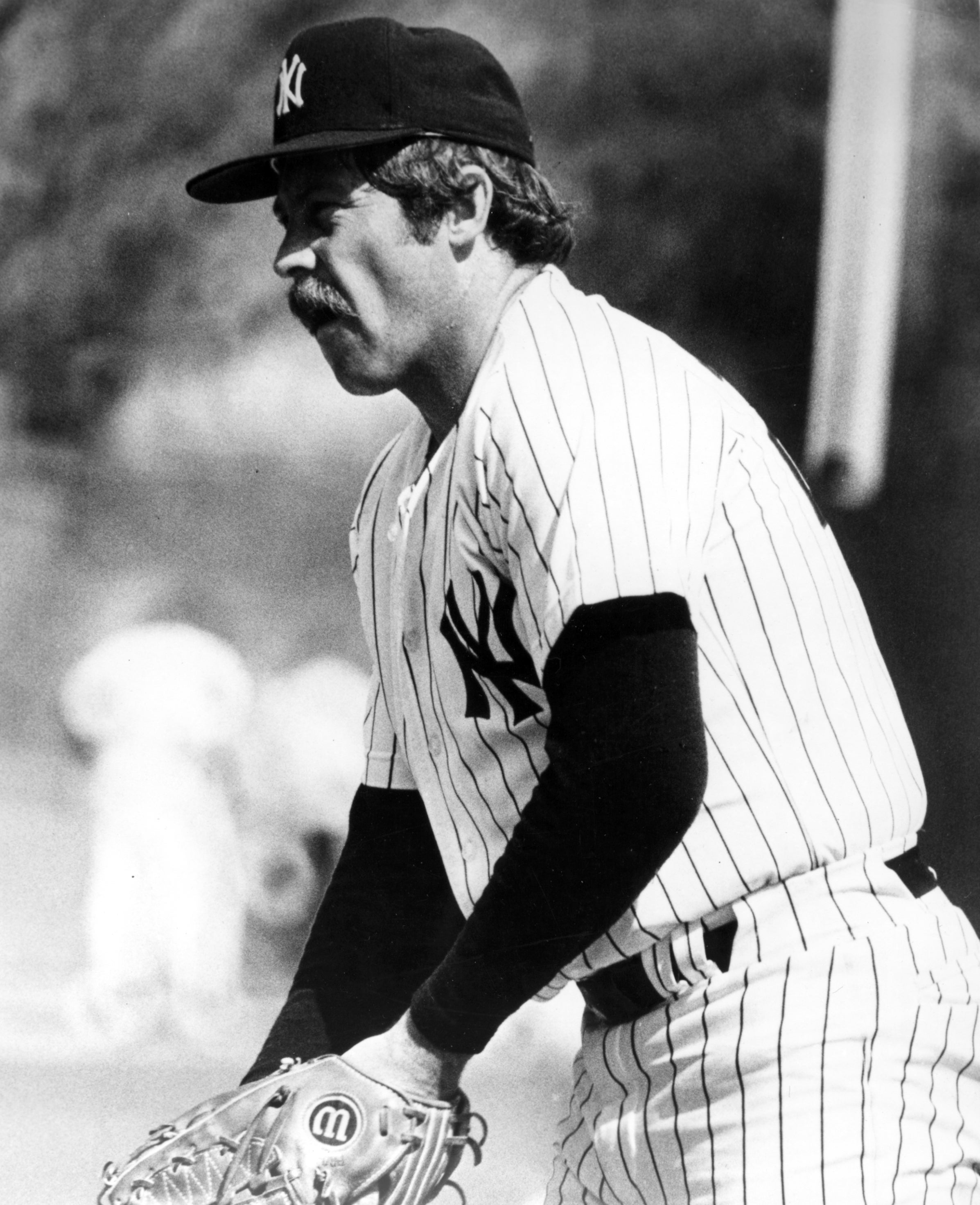

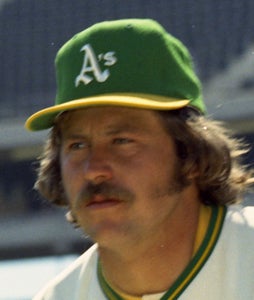

Five years after Pete’s journey began, he continues to fight ALS every day, refusing to cower in the face of a devastating disease which has taken away his ability to walk, talk, eat and even breathe. But while Pete – like Lou – was content with shying away from attention on the ballfield, he has spearheaded a public crusade within the medical community. And now, with today’s announcement of a new exhibit at the Hall of Fame, “ALS and Baseball,” the story of Pete, Lou and Catfish Hunter will continue to be told, to the hundreds of thousands of visitors the Hall of Fame receives every year. The announcement came as part of a weekend long celebration of Frates and his fight against ALS, during which the Boston College Men’s Baseball Team played two scrimmages in support of their former teammate.

For Nancy Frates, the weekend could only be described in two words.

“Full circle. My two kids always wanted to come to Cooperstown, but it’s a five-hour drive. We used to work all summer, until the fall, and the spring with all the Little League teams – we never brought our kids here because we could never give up the five hours to come out here,” Nancy said. “Finally one of his friends’ parents were going to Cooperstown and they brought Pete. So I think the fact that Pete has been here is something that really makes it the hardest part of me being here right now, without him. But the fact that he’s actually been here, it’s unbelievable. He wanted baseball to take hold of this disease, and it has happened.”

There’s a part of Lou Gehrig’s speech – well known to many – where Gehrig says:

Look at these grand men. Which of you wouldn't consider it the highlight of his career just to associate with them for even one day?

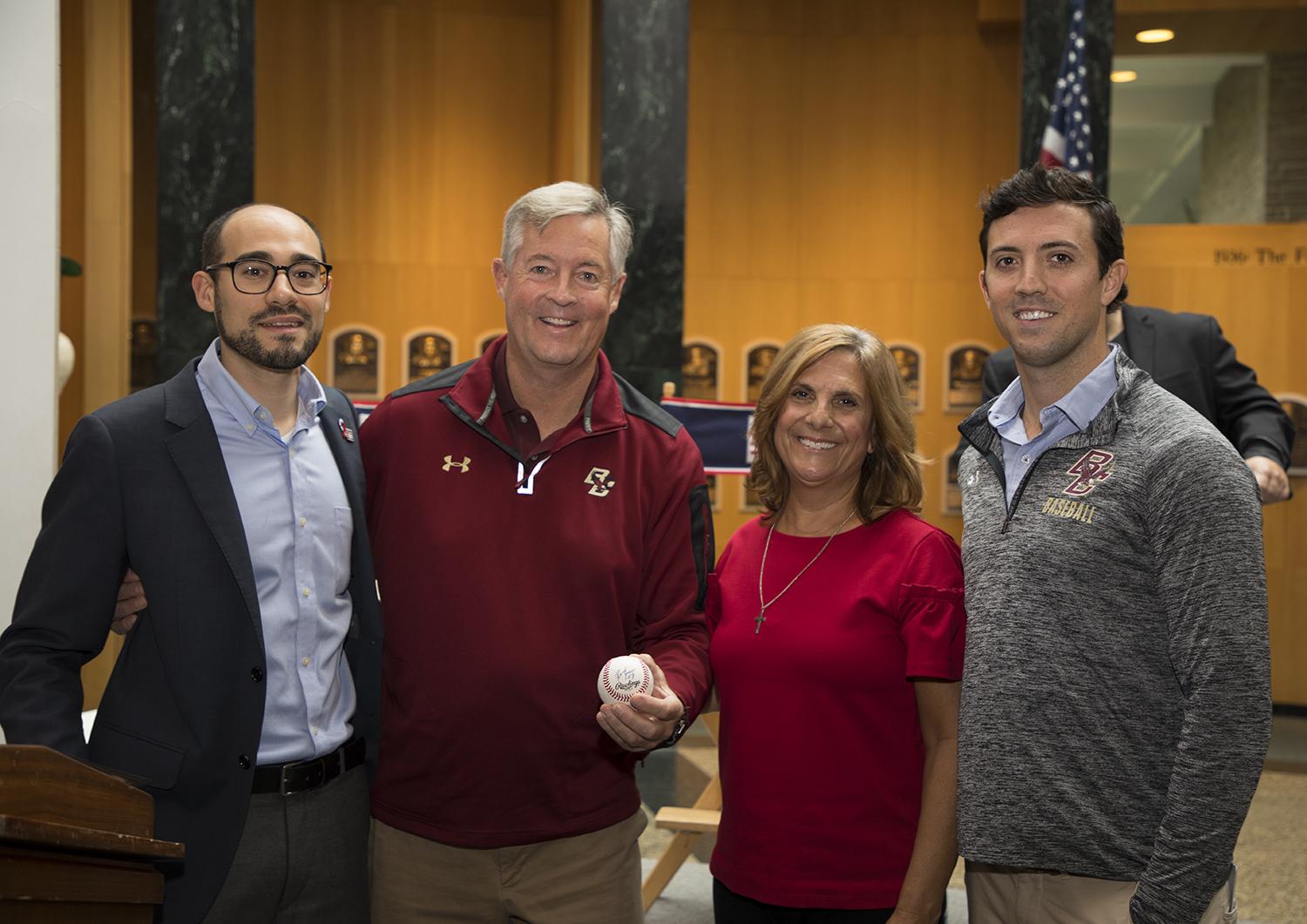

To begin the Hall of Fame's ALS Awareness Weekend, John Frates, Nancy Frates, author of “The Ice Bucket Challenge: Pete Frates and the Fight against ALS” Casey Sherman and Boston College Men's Baseball Coach Mike Gambino speak on an ALS Awareness panel. (By Photographer Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Today, the man Lou is referring to is Pete. But their ties will go beyond this weekend. And while they may be linked by trauma, it’s their character in the face of adversity that will unite them forever.

“This disease was named after Lou Gehrig. But I think Lou Gehrig would be very proud of Pete that for the fact that ALS is branded now,” said Pete’s brother, Andrew Frates. “It’s not Lou Gehrig’s disease any more, it’s ALS. People are learning what ALS stands for – Amyltrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Having it branded ALS, rather than Lou Gehrig’s disease, is huge for the ALS community because now people can start Googling ALS, Googling other symptoms of what that is. I think Lou would be proud of Pete for that.”

Alex Coffey is the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum