- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: In 1922, the Browns turned from loveable losers into contenders

#GoingDeep: In 1922, the Browns turned from loveable losers into contenders

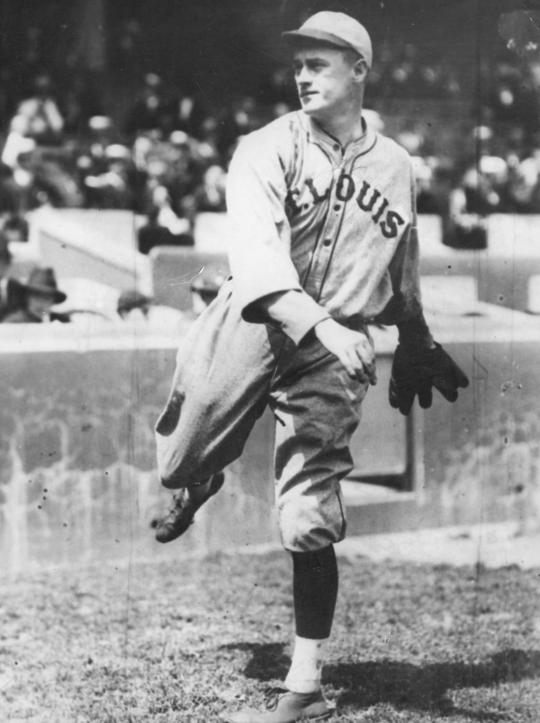

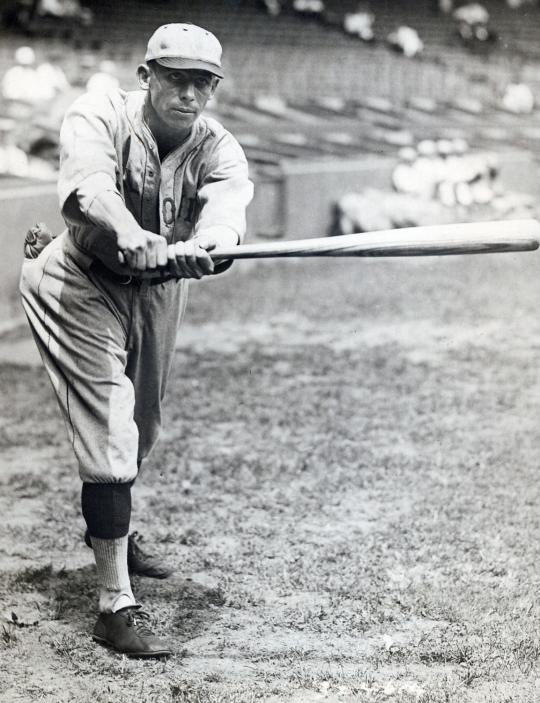

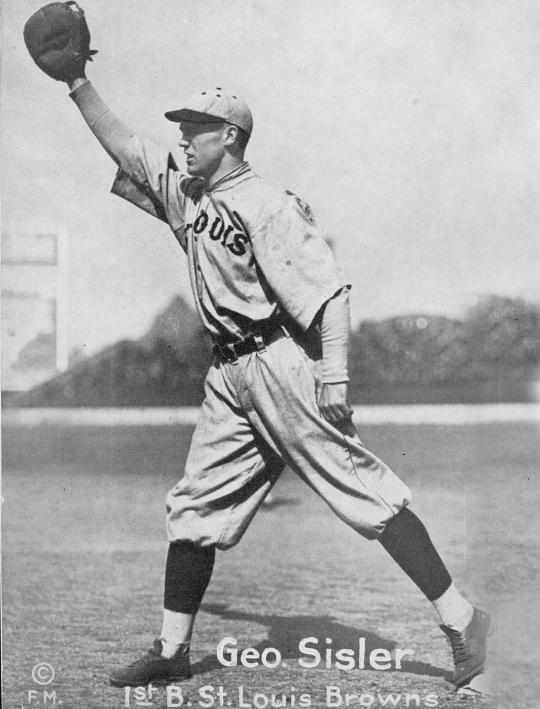

Among the artifacts at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum is the first baseman’s glove used by George Sisler in the early 1920s. It is an object of beauty, well-worn by the best of the best and almost begging to be used once more.

There are thousands of such treasures in Cooperstown, each with its own story. But this mitt tells an especially compelling tale.

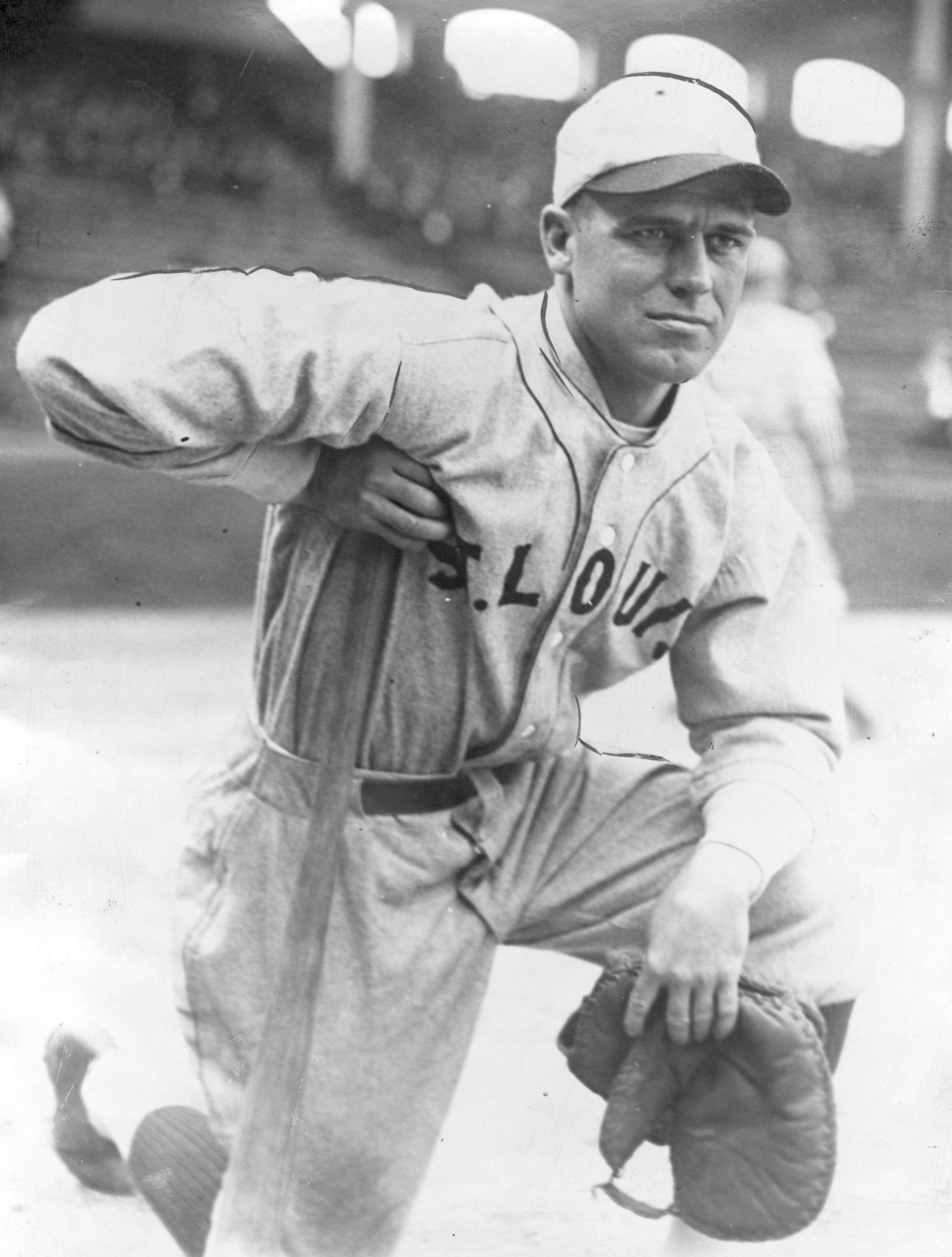

For one thing, it belonged to the man Ty Cobb once called “the perfect ballplayer.” For another, the front of the mitt resembles Sisler’s own face – wide and open, handsome and weathered by the summer sun. For yet another, if you turn it over, you will see a distinctive horseshoe frame with the Rawlings tag at the bottom, calling to mind the broad shoulders that once carried the 1922 St. Louis Browns on them.

In his classic 1949 book, Baseball’s Greatest Teams, Tom Meany included those ’22 Browns among the 16 teams he deemed the best. Sisler batted .420 that year thanks to an AL record 41-game hitting streak, while leading the American League in stolen bases (51) and driving in 105 runs, often in pain.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Those Browns were as glorious and well-crafted as Sisler’s glove, winning 93 games and winning over a million St. Louis hearts. But if you look closely at the mitt, you’ll notice a forked kink that leads to the webbing. That flaw is also a symbol, a mark of the regret that Sisler and his teammates must have felt for the rest of their lives.

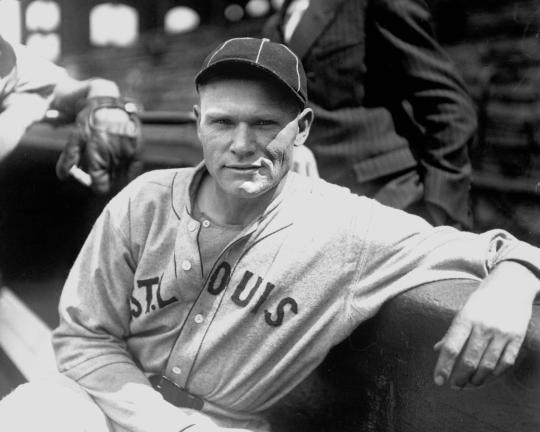

Meany’s chapter title for the ’22 Browns cuts to the quick: “Close But No Cigar.” Despite having six regulars who hit over .300 and four who drove in more than 100 runs, despite the presence of 24-game winner Urban Shocker and AL home run leader Ken Williams (39), the Browns finished the season one game behind the New York Yankees.

As Meany wrote at the end of the chapter, “It was a great team, that ’22 bunch, great but not lucky. And in baseball as in life, you often have to be both.”

But 100 years later, they are still a team worth celebrating, even more so than the 1944 Browns, the only St. Louis American League team to win a pennant. The cast of characters alone threatens plausibility – the ice tycoon who owned them, the ace who would die of heart disease six years later, not one but two medical students, several Army veterans, a department store accountant, the son of a governor, guys called Baby Doll, Shucks, Shock, Spooks, Sizzler, Rasty and Dixie, and a darn good pitcher with the Dickensian name of Elam Vangilder.

As for the plot of the ’22 season, there were all sorts of twists and turns, moments of comedy and tragedy, acts of hubris and a climactic scene at what was called “The Little World Series,” in which police had to break up a fight involving New York sportswriters and Brownie rooters. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves…

The story of the ’22 Browns really begins on the campus of the University of Michigan in 1911, where and when the son of Cassius Clay Sisler was a freshman engineering student. George had been a three-sport star at Akron (Ohio) High School, but freshmen weren’t allowed to play on the varsity teams. Once the Michigan baseball coach saw him pitch in a practice session, though, he couldn’t wait to get him on the field. The coach just happened to be someone at the heart of many baseball stories – Branch Rickey.

In his sophomore year, Sisler helped the Wolverines finish 22-4-1, but shortly thereafter, Rickey left to take a job in the front office of the Browns, for whom he had once been a catcher. Still, he kept close watch on Sisler. So did the Pirates, who acquired his contract back in 1912. But because he signed before the age of consent, Rickey challenged the contract and won, so Sisler became a Brown in 1915 for a $5,000 bonus and $300 a month.

By then, Rickey had become the manager of the team and had to decide whether George should become a pitcher – he had a 2.83 ERA in 70 innings – or a first baseman – he hit .285 in 81 games with speed and pop. The Mahatma made the same decision that the Red Sox would soon make with their George, namely Ruth.

But then the Iceman Cometh. Philip De Catesby Ball, who made his fortune making ice, bought the Browns for around $425,000 in 1916. Ball had once been an amateur catcher whose baseball career ended in a knife fight in a New Orleans bar, so he and the more temperate Rickey weren’t exactly a match. Ball fired Rickey, who went to work down the road for the Cardinals in 1917.

Among the assets that Rickey left Ball were Sisler, stalwart catcher Hank Severeid and Jack Tobin, an outfielder who was the son of a St. Louis bricklayer. The new owner chose Bob Quinn, another former minor league catcher, to help him build a winner. As Sisler blossomed into one of baseball’s best first basemen, the Browns got better. Center fielder Baby Doll Jacobson, who earned his name in the minors when he homered after a band had played, “Oh, You Beautiful Doll,” arrived in 1915.

Quinn picked up his future ace, Shocker, in a steal of a trade with the Yankees in 1918, while the superb fielding shortstop Wally Gerber and the power-hitting left fielder Williams became fixtures in 1919.

Still, the Browns didn’t regularly finish above .500. So after the 1920 season, Ball and Quinn fired manager Jimmy Burke and hired Lee Fohl, another former catcher who had managed the Indians with some success.

Two more new arrivals filled out the infield: Third baseman Frank Ellerbe, whose father had been the governor of South Carolina; and second baseman Marty McManus, a World War I vet who had once kept the books for a Chicago department store. Thanks in large part to the hitting of Sisler (.371), Tobin (.352), Jacobson (also .352) and Williams (.347 and 24 homers), and the decision that allowed Shocker (27-12) to continue using his spitball, the Browns finished third with an 81-73 record.

With some optimism for the ’22 season, the Browns headed to their new Spring Training home of Mobile, Ala. Their biggest concern was pitching depth behind Shocker, Vangilder and Dixie Davis, but they were also buoyed by the certainty that the Yankees would have to play the first six weeks of the season without Babe Ruth and Bob Meusel, who had run afoul of Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis for participating in a barnstorming tour after the 1921 season.

The Browns arrived at the magnificent Battle House Hotel in time for Mardi Gras and had to contend with all kinds of distractions, including horse racing season. If you were to sit in the lobby in March of ’22, beneath the murals of George II and George Washington, you could see ballplayers mingling with jockeys, gamblers, swells and just plain fans.

But it was another George who was the biggest attraction. According to a newspaper account in Roger A. Godin’s invaluable book, The 1922 St. Louis Browns, Sisler overheard some starry-eyed kids from northern Alabama asking if “The Sizzler” might be around the lobby, so he went over to them, introduced himself and invited them to be his guests at that afternoon’s game.

When a newspaperman mentioned what a nice gesture that was, George blushed and said: “Say, I wouldn’t hurt a kid’s feelings for the world. I was a kid myself.”

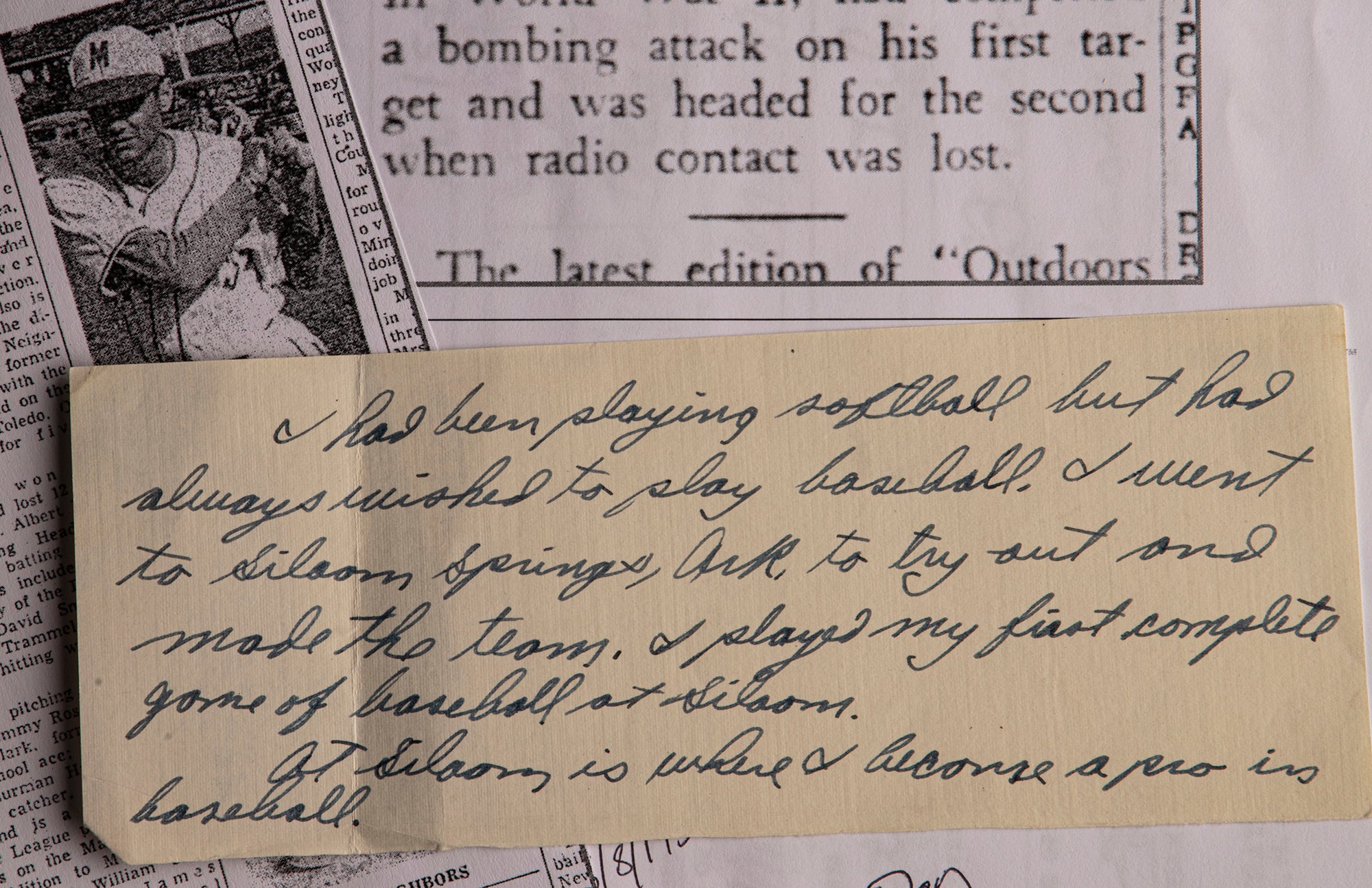

Also passing through the lobby largely unnoticed were two Browns pitchers with medical training. One was right-hander Wayne “Rasty” Wright, who was back after a two-year hiatus studying at Ohio State and learning his craft in the minors. The other was rookie Hub “Shucks” Pruett, a slight left-hander with a fadeaway as baffling as his background – he divided his time between baseball and the St. Louis University School of Medicine. As it turned out, both would help heal the Browns’ lack of pitching depth.

When the Browns returned to St. Louis, they had a spring record of 17-0. And after a four-game exhibition series with the Cardinals, they were 20-1. Bring on the Yankees.

On April 12, the Browns opened the season with a 3-2 win over the White Sox at Comiskey Park. The winning pitcher was Shocker, who owed his success to a broken middle finger that hooked around the ball – and a fiery nature. After winning their first three games, the Browns lost four of their next five to fall to fifth place. But then Ken Williams, the slugger from Grants Pass, Ore., went on a tear, hitting nine homers in seven games as the Browns finished the month 11-5 and atop the AL standings. For his heroic efforts, Williams was given a phonograph at a special ceremony on April 30, leading the Post-Dispatch to joke: “Having given him a new phonograph, the fans expect Williams to break all the old records.”

As The Fates would have it, the Browns’ first game with the Yankees was scheduled for May 20 at the Polo Grounds, the very day Ruth was allowed to resume play. At the time, St. Louis was in second place, two games behind the Yankees.

The crowd of 38,000 saw a pitching duel between Shocker and Sad Sam Jones, and they began to file out with the Yankees ahead, 2-1, the bases empty and two outs in the top of the ninth.

What then happened is a story unto itself. Suffice to say, The Fates have a sense of humor. Two pinch-hit singles, an out call at first that was waved off when the ball was bobbled, a single, a walk, another walk and a grand slam homer by Baby Doll gave the Browns an 8-2 win and pulled them within a game. Alas, the Yankees won the next two games of the four-game series, so when Shocker beat the Yankees again on May 23, the Browns were right back where they started.

The two teams next met for another four-games series at Sportsman’s Park on June 10-13, with the Browns 2.5 games behind and 22,000 fans hoping against hope. Shocker again got the call, but he was weary, and when the Yankees hit him hard in the top of the third, he got testy and threw three straight pitches under the chin of opposing pitcher Carl Mays, after which Mays took his bat and his own temper to the mound. Only the intervention of umpire Billy Evans prevented an all-out brawl. The Yankees won a 14-5 laugher. Having only gone three innings, Shocker insisted on starting the next day, but the result wasn’t much better – the Browns lost, 8-4, to fall 4.5 games behind.

Enter Shucks Pruett. He had gotten the nickname because that was the strongest curse word he could muster, and he got the start because Fohl didn’t have much of a choice.

The little southpaw and future physician allowed only six hits and struck out Ruth three times in a 7-1 victory, much to the delight of the Monday Ladies Day crowd. Perhaps this informed Pruett’s choice of specialty when he became a doctor: Obstetrician.

It certainly inspired this poem by L.C. Davis of the Post-Dispatch:

There was a young fellow named Pruett

Who was a great pitcher and knew it.

This scintillant youth

Humbled George Herman Ruth

When other great stars failed to do it.

When the Browns won again the next day, 13-4, they were right back where they had started the four-game series. By winning eight of nine games, they took over first place, which is where they sat at the end of June, three games up on the Yankees.

They met again seven more times in July, with the Browns losing two of three in New York, and then three of four in St. Louis. Adding insult to injury, the Yankees had traded three utility players and $50,000 to the Red Sox for star third baseman Joe Dugan and outfielder Elmer Smith, igniting protest letters to the Commissioner from both the St. Louis Rotary Club and the Chamber of Commerce. But because they went 13-7 against the rest of AL, the Browns were still in first at the end of the month. Plans were made to add 7,000 temporary bleacher seats to Sportsman’s Park for the possible World Series. Yes, The Fates were being tempted.

At the end of August, the clouds began to gather over the Polo Grounds for a rainy four-game series – and over the Browns, who lost three of them. They went into September in second place, 2.5 games behind the Yankees. But then they won five of six to climb back into first on Sept. 5, which was perfect timing because as that day’s St. Louis Stars & Times proclaimed:

Pennant Chasers To Be Honored Tonight.

The members of the Browns, players and club officials alike, were being presented gold watches by the “Boost the Browns” club on the stage of the Missouri Theater to thank them for such an outstanding season. Much of the money for the watches had come from patrons of the theater, who had been dropping their change into a barrel in the lobby. The mayor spoke, George Sisler thanked the boosters and the recipients were given watches engraved with their names and the message: “A Gift From The Citizens of St. Louis.” After which, the theater showed Her Gilded Cage, starring Gloria Swanson.

There was another upcoming feature that the citizens were excited about: “The Little World Series,” the three games between the Browns and Yankees at Sportsman’s Park Sept. 16-18. As clerks in the basement processed an avalanche of actual World Series requests, fans began to line up for the Saturday opener at 11 p.m. on Friday. With the Browns only a half-game behind, they were worried about the two Georges – Ruth for his bat and Sisler for his right shoulder, which he had badly injured against the Tigers on Sept. 11.

The fans were relieved to see Sisler take his swings in batting practice and even more so when he ran out to first base. On the mound was Shocker, and after giving up single runs in the second and third, he settled into a pitcher’s duel with Bob Shawkey, who allowed one run in the sixth. So it was 2-1 in the bottom of the ninth when Eddie Foster lofted a ball to right center. As Yankees outfielders Bob Meusel and Whitey Witt converged, a bottle flew out of the stands and struck Witt on the forehead. Meusel had made the catch, but Witt was on the ground unconscious. The sickening sight, George Sisler later told a reporter, “had taken the heart out of the Browns.” Sisler and Williams quickly made outs to end the game in a 2-1 victory for the Yankees.

There was a huge, collective sigh of relief the next day when Witt led off the game for the Yankees. But there was also a sense of urgency – the Browns needed to win. And that they did, 5-1, behind a five-hitter by Pruett, who gave up a solo homer to Ruth in the sixth. Sisler extended his hitting streak to 41 games, but the hitting hero was Williams, who hit his 38th homer, a two-run blast in the eighth.

So the stage was set for the rubber game on Monday. Fohl gave Dixie Davis the start against Yankees ace Bullet Joe Bush, and when he took the mound in the top of the ninth, Davis had a 2-1 lead and the fans were literally whistling Dixie. But after Davis failed to snag a line drive hit back to him, then was victimized by a passed ball, Fohl brought in Pruett, who gave up a bunt that Severeid failed to turn into an out. When Shucks walked the next batter to load the bases, Shocker came on and eventually faced none other than Whitey Witt, whose head was swathed in gauze. He got his revenge by lacing a two-run single to give the Yankees a 3-2 lead.

At which point, all hell broke loose in the section of the stands where the writers were seated. According to Meany, a fan reading over the shoulder of New York Tribune columnist W.O. McGeehan took offense at what he was typing and hit him on the head with a seat cushion, saying, “Send that back to New York.” Sid Mercer of the New York Globe, who once was the road secretary for the Browns, then rose to his feet and belted the fan on his chin. As Meany put it, “It took the intervention of the police before the profession of the arts and letters resumed the even tenor of its way.”

The game wasn’t over – Bush still had to face the heart of the Browns’ order in the bottom of the ninth. But Sisler grounded out to end his 41-game hitting streak, Williams popped up to second and Jacobson grounded out. The scoreboard read New York 3, St. Louis 2. The faces of the fans read utter defeat.

The Browns weren’t dead yet, though. They got their act together the last week of the season and found themselves only two games behind with two games left to play on Saturday, Sept. 30, when they were hosting the White Sox while the Yankees were in Boston. But instead of starting future Hall of Famer Herb Pennock, Red Sox manager Hugh Duffy went with Alex Ferguson, who failed to retire a single batter. Thus, the Yankees won, 3-1, to clinch the pennant.

The Yankees were swept by the Giants in the World Series, leaving the Browns to think they could have done better. Sisler won the MVP Award that year, and got to meet W.C. Fields backstage in Boston. But he would never get to play in a World Series, even though he had a lifetime average of .340 over his 15-year career. Inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1939, he shared a reunion with Bob Quinn in 1948 when Quinn was named the Museum’s president.

Severeid would play in two Fall Classics, one for the Senators in ’25, the other for the Yankees in ’26. Shocker, too, played in the ’26 Series, but by then he was suffering from a heart ailment that forced him to sleep sitting up. He would die of heart failure in 1928, a year after winning 18 games for the Yankees.

By the time Pruett finished his career in 1932, he had the distinction of being the toughest pitcher Babe Ruth ever faced – he struck him out 13 times in 24 at-bats. Years later, he had a chance meeting with the Bambino and told him, “I want to thank you for putting me through med school. If it wasn’t for you, no one would have heard of me.”

While Rasty Wright never did become a doctor, he did coach the baseball team at Ohio State for a time. And in a way, he made it into the Baseball Hall of Fame – among the artifacts on exhibit in the Museum’s Sandlot Kids Clubhouse is the gold watch presented to Wayne Wright from The Citizens of St. Louis on Sept. 5, 1922.

As a remembrance of that storied team, the watch works just fine.

Steve Wulf is a freelance writer from Larchmont, N.Y.