- Home

- Our Stories

- Bud Fowler’s story has deep roots in Central New York

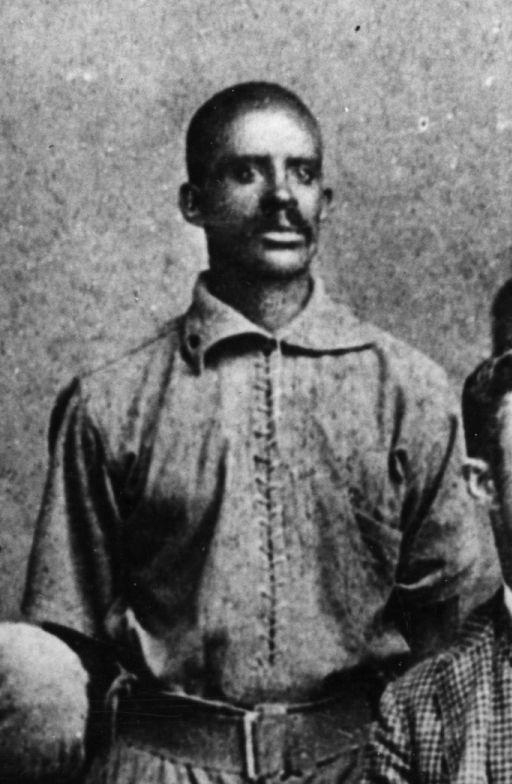

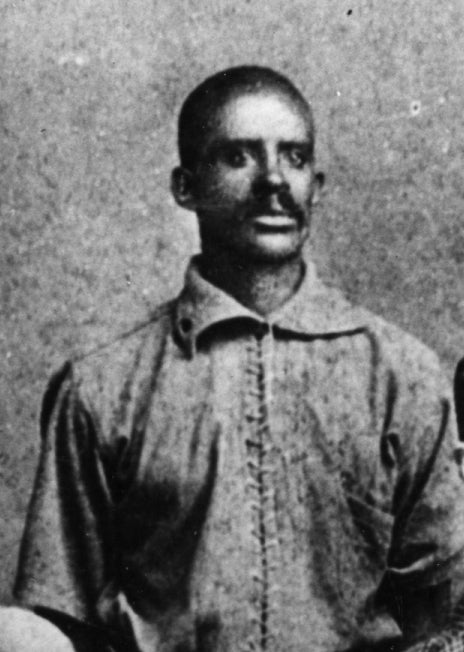

Bud Fowler’s story has deep roots in Central New York

For 74 years, John W. Jackson lay in an unmarked grave only 30 miles from Cooperstown, underappreciated and in anonymity.

Many years of meticulous sleuthing would eventually lead to a long overdue headstone that reads in part “Black Baseball Pioneer.” That man, who gained fame as a ballplayer named Bud Fowler, will have a bronze plaque in Cooperstown this summer.

Fowler and Buck O’Neil were elected to the Hall of Fame in December 2021 by the Early Baseball Era Committee. But unlike most of his fellow Hall of Famer brethren, Fowler had been all but forgotten because of the times in which he shined on the diamond.

“If he had only been painted white, he would be playing with the best of them,” the Dubuque (Iowa) Times said of Fowler in 1890.

Fowler’s amazing story, though, initially came to light again in the 1950s, when Herkimer (N.Y.) Evening Telegram managing editor Lee Allen had heard rumors of a Black baseball player being buried in nearby Frankfort.

Allen, a successful baseball author who in 1959 would be named historian at the Hall of Fame, had a passion for discovering ballplayer histories. It was after paging through past issues of his newspaper that he discovered a note of the death of a player named Jackson in 1913.

Born John W. Jackson in Fort Plain, N.Y., in 1858, he adopted the name Bud Fowler during a nomadic playing career. Often acknowledged as the first Black professional baseball player, his father, a former slave, moved his family to nearby Cooperstown – future home of the Hall of Fame – when his son was a youngster.

During a nearly two-decade long career on the diamond, Fowler starred at second base and on the mound for both Black and integrated teams despite often facing severe backlash and banishment from teammates and opponents due to his race.

“Captain Fowler of the Montpeliers is a colored man and a first class balltosser in every respect,” reported the Rutland (Vt.) Herald in August 1877. “The Montpeliers are fortunate in securing him.”

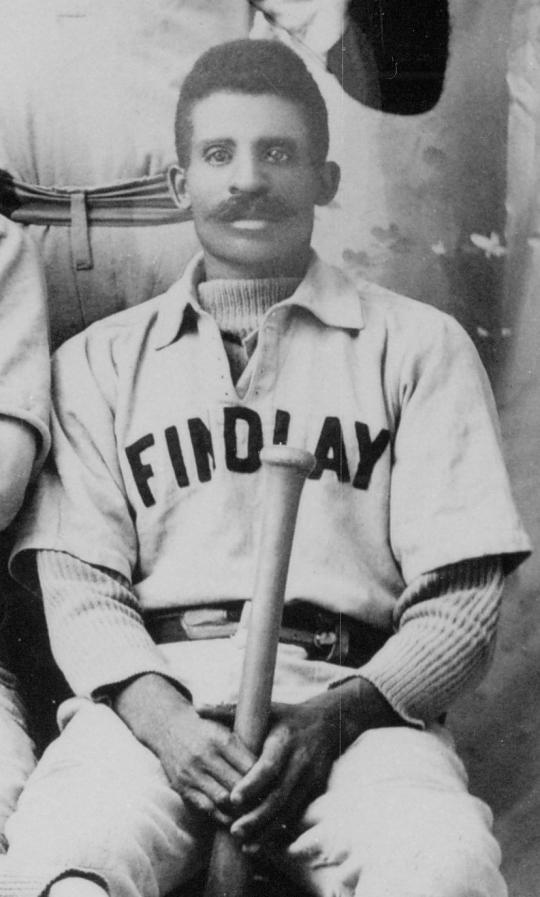

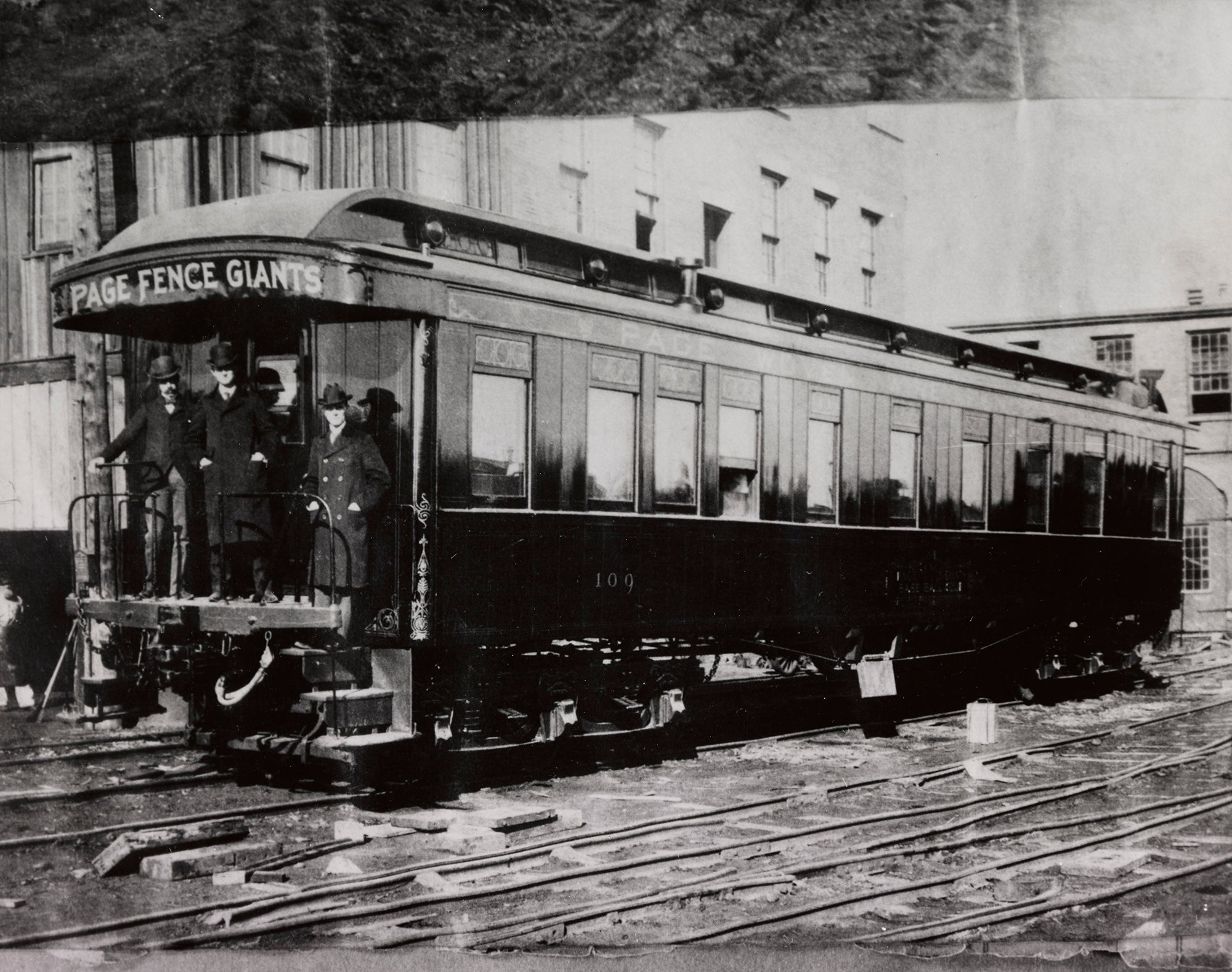

Later, Fowler established barnstorming teams of his own such as the acclaimed Page Fence Giants.

When the National League’s Cincinnati Reds played an exhibition against the Page Fence Giants in April 1895, the Cincinnati Enquirer wrote of Fowler – who was the captain and second baseman of the team – in glowing terms.

“Fowler has been playing baseball for 26 years, and he is yet as spry and as fast in his actions as any man on his team,” the Enquirer wrote. “He has no charley horses or stiff joints, but can bend over and get up a grounder like a young blood.

“All together he is a wonder. Fowler attributes his remarkable condition to the fact that he has always taken care of himself. Wine, women and song have played a very little part in the life of the veteran of the diamond. Go out and see him play second base this afternoon.”

But in the same newspaper article, the negative thinking toward Blacks in society at that time was plain to see: “Along about the third inning, when the score stood 2 to nothing in favor of the Giants, you could have tossed a ripe Georgia watermelon or a fat possum … down among that gang of colored rooters in the pavilion and they would have kicked it aside and gone on looking at the game.”

Despite his numerous accomplishments on and off the field, the last years of Fowler’s life unfortunately involved deteriorating health and financial woes. Eventually he moved in with his sister Harriet in Frankfort, N.Y., a village 35 miles west of his birthplace.

When Fowler passed away at the age of 54 on Feb. 26, 1913, his sister could not afford a gravesite, so her brother was buried in a potter’s field in Frankfort’s Oak View Cemetery without a headstone to mark the spot.

Fast forward to July 25, 1987 – the day before the National Baseball Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony would take place in Cooperstown – and a special service in Fowler’s memory was held at Frankfort’s Oak View Cemetery, located at 110 Cemetery Street near the Herkimer County Fairgrounds.

Proclaimed Bud Fowler Day by Frankfort Mayor Francis Grates, the Saturday afternoon graveside ceremony attracted a crowd of approximately 100, which included Little Leaguers, baseball fans, historians, local politicians, as well as Hall of Famer and former Negro League outfielder Monte Irvin, then working in the Commissioner’s Office, and former Negro League first baseman and manager Buck O’Neil, then a scout with the Chicago Cubs.

“If it hadn’t been for fellows like him,” Irvin told the crowd that day, “breaking the color barrier would have been delayed a long, long time.”

The Fowler event was highlighted by a simple headstone purchased through donations by the Society for American Baseball Research. It reads:

John W. Jackson

(Bud Fowler)

1858-1913

Black Baseball Pioneer

Erected by SABR

July 25, 1987

Longtime broadcaster Keith Olbermann, in a recent conversation, said he was one of those who donated toward the purchase of the Fowler headstone.

“I was an ardent reader of (and contributor to) all the SABR publications and recall reading a mention that donations were being accepted for the Fowler headstone,” Olbermann said.

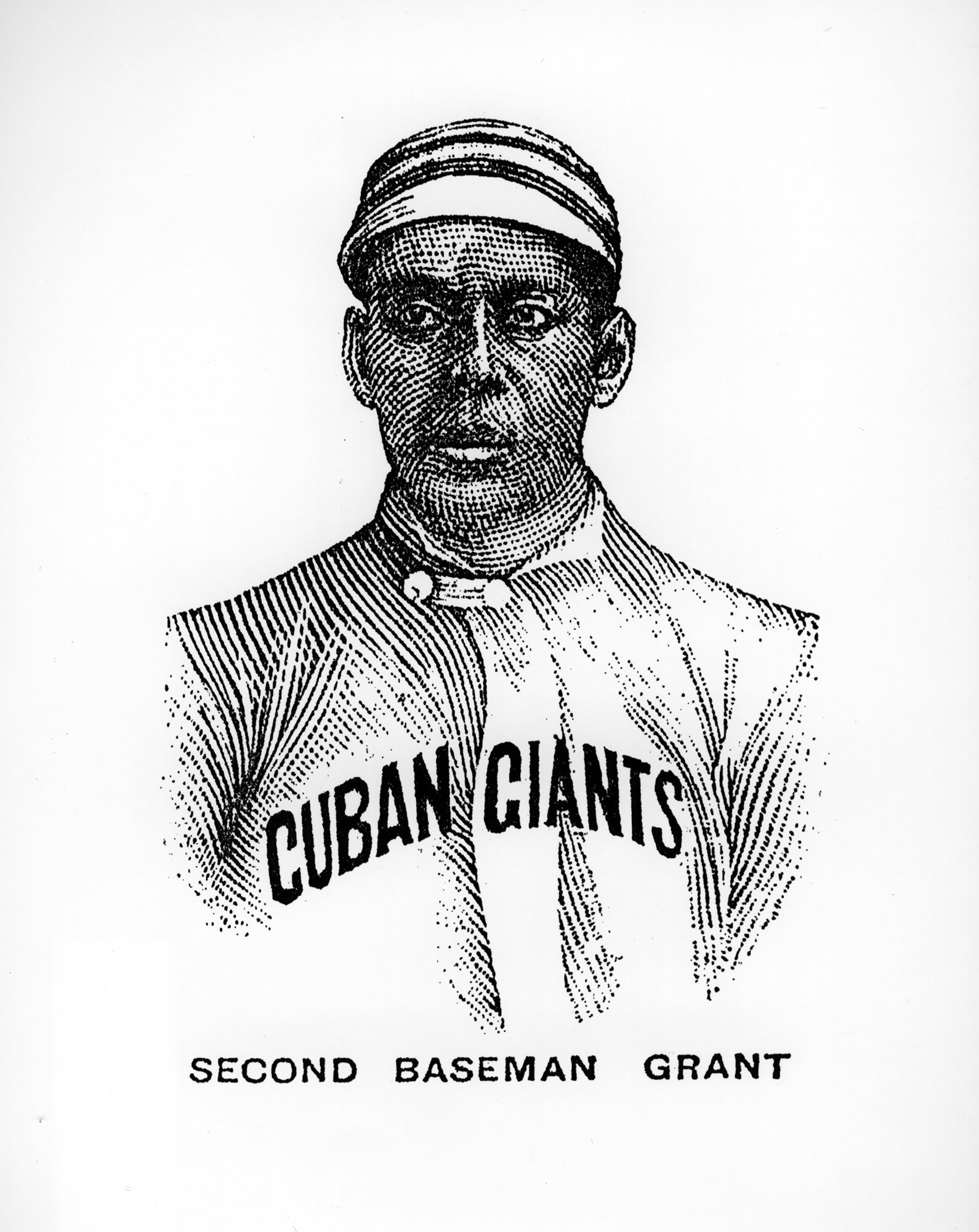

“You'll remember that in 1987 guys like Fowler and Frank Grant and George Stovey were trapped in a figurative no man’s land. They weren’t the 20th century Negro Leaguers who were already well known enough and they also weren’t the remaining founders of the game being admitted to Cooperstown. They were somewhere in between, with those skeletal minor league statistics that on an unconscious level made their contributions – and their travails – seem smaller than they were.

“Fowler's personal connection to Cooperstown just added another dimension to it. So I was honored to help, even in a small way.”

Fowler’s personal connection to Cooperstown led the village in which he learned the game of baseball to honor him in 2013 by naming a street Fowler Way that leads to Doubleday Field.

The Fowler memorial – held 40 years after Jackie Robinson broke the modern color barrier – marked the culmination of over 20 years of research into the career and life of the man.

“Bud Fowler Day is a triumph of research. Fifteen years ago he was a rumor,” said SABR Executive Director Lloyd Johnson that day in 1987. “A man so forgotten 74 years ago is probably the most famous citizen of Frankfort today.

“It’s a baseball-crazy world. And this is a significant event in local history.”

An editorial in the Herkimer Evening Telegram a few days later somewhat presciently made the case for Fowler’s Hall of Fame inclusion.

“We hope the Fowler story isn’t over,” it read. “His credentials have Hall of Fame written on them. His efforts have the right to be recognized. Long before Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier, Fowler had paved the way for Blacks to play organized ball. It’s unfortunate his deeds went unrecognized.”

Reflecting on the 1987 ceremony, Johnson said in a recent interview that he’s happy that Fowler is getting some long overdue recognition considering he was lost to the baseball world for generations.

“He is a person who paved the way for many, many players,” Johnson said. “He's certainly a groundbreaker and he could flat out play baseball. His talent was his baseball instincts. Bud Fowler was a ballplayer. He was the best player on almost every team he played. He was a pioneer and did his best to spread black baseball around the country. Not quite like Johnny Appleseed but almost.”

In September of 2021, a few months before Fowler was elected to the Hall of Fame, SABR’s Cliff Kachline Chapter, which serves the Central New York area including Cooperstown, paid for the Fowler headstone to be cleaned.

“We realized all along the magnitude of Bud Fowler’s contribution to the game,” said Kachline Chapter President Mike Houser. “We felt we owed it to SABR group from 1987 who initially had the stone made, that we should try to help keep that legacy going and cleaned it up. It looks brand new.

“Once Fowler is officially inducted into the Hall of Fame, we also plan to have something etched into the upper section of the stone, currently a blank area, to denote that he is a Hall of Famer.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum