- Home

- Our Stories

- Fifty years ago, the Big Apple honored the Great One

Fifty years ago, the Big Apple honored the Great One

It was New Year’s Day 1973 and a childhood moment I’ll never forget.

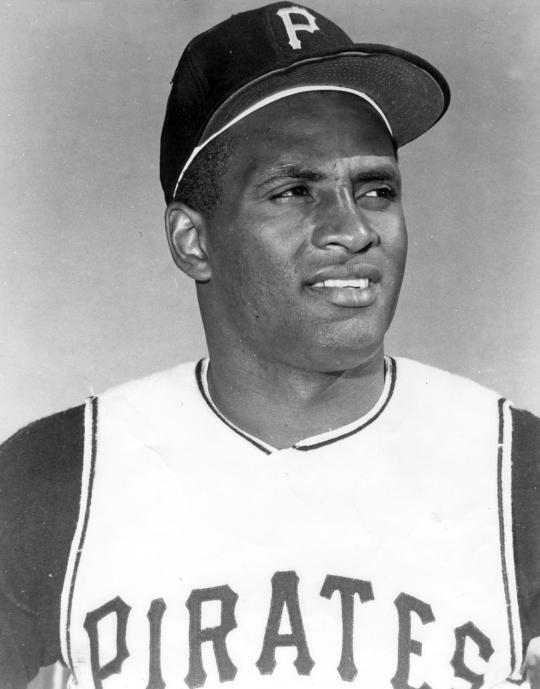

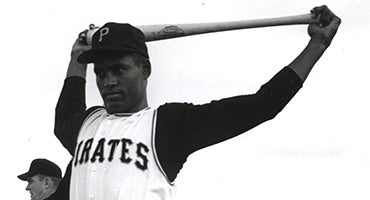

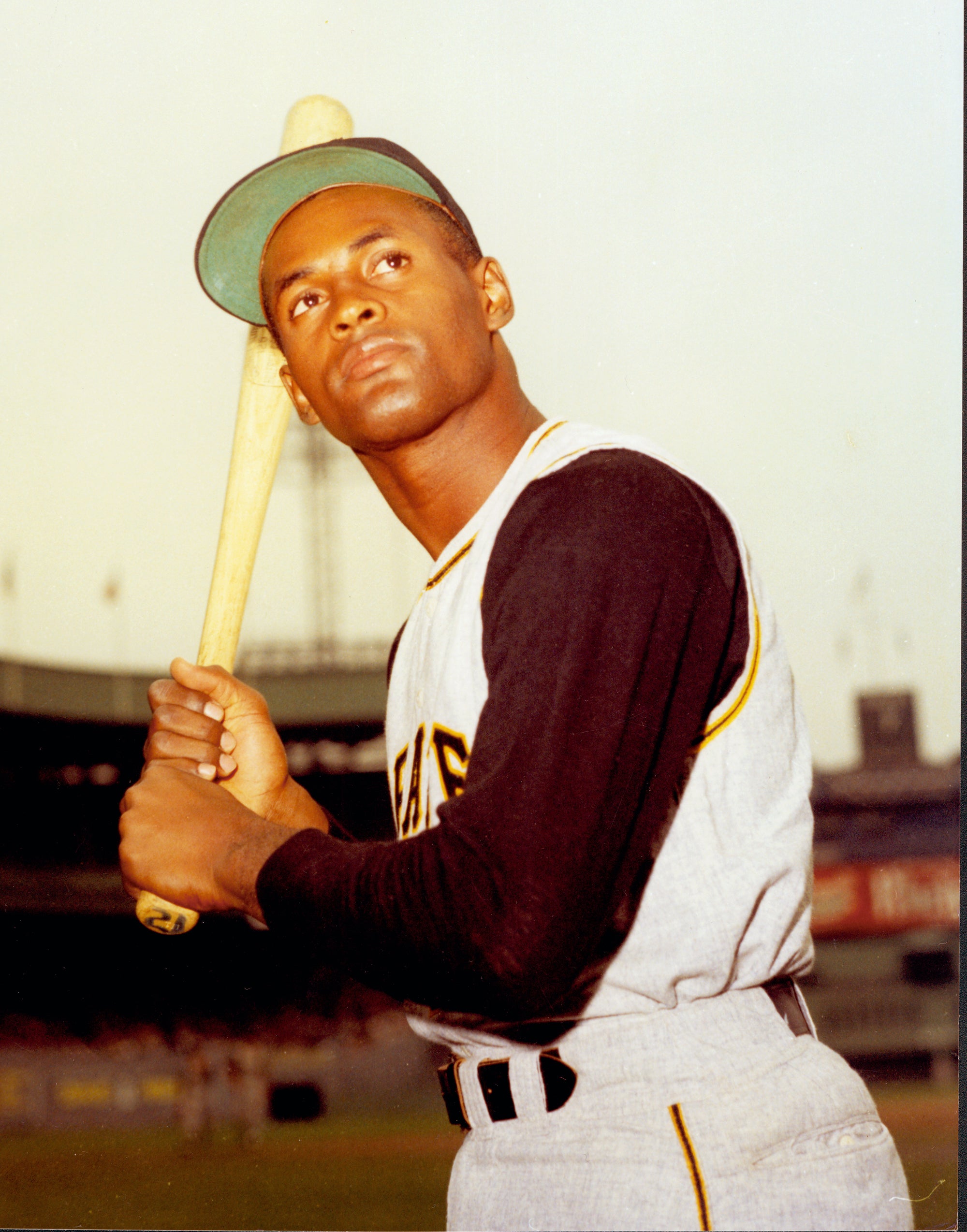

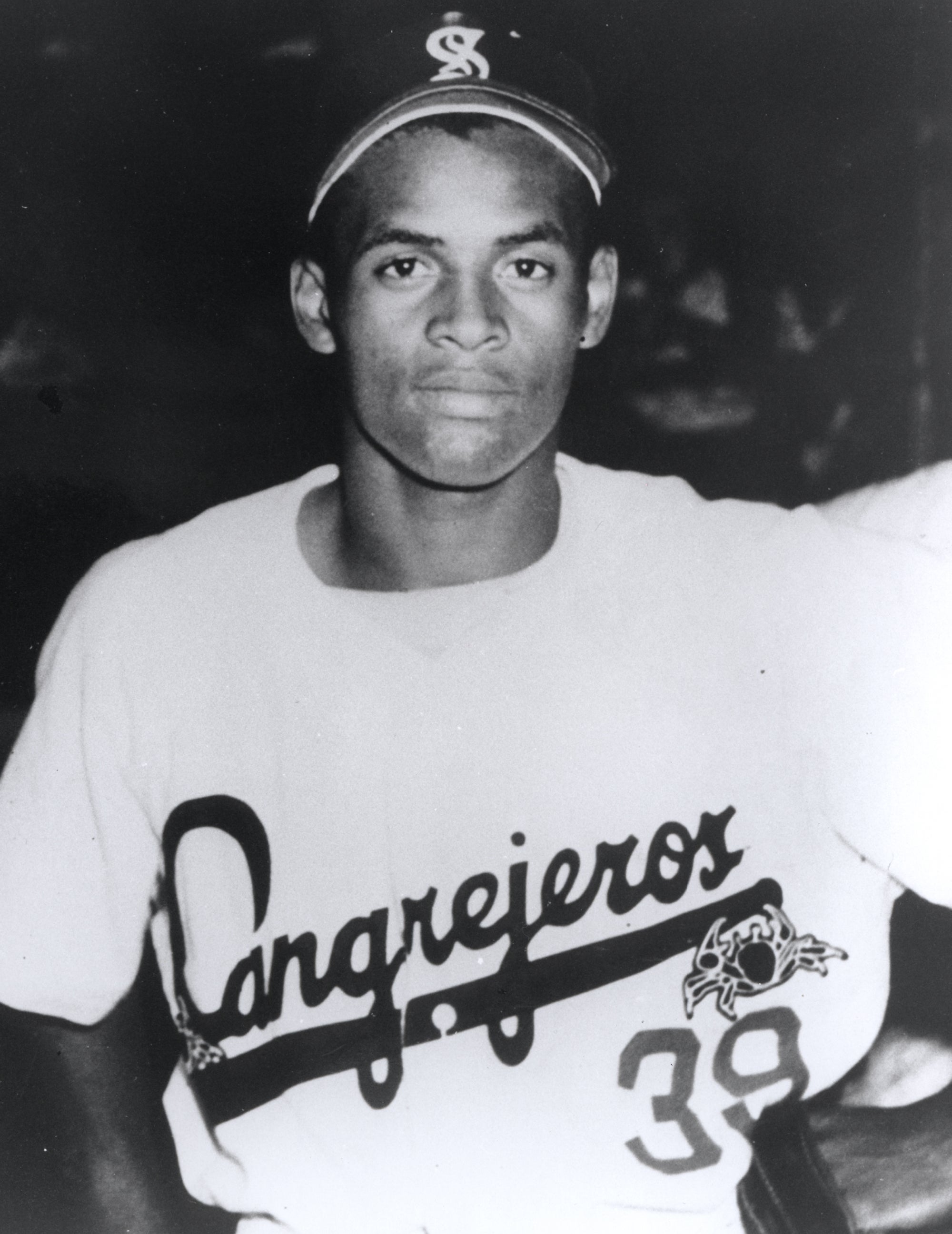

That sorrowful date was my earliest recollection of witnessing my late father shed tears over the death of someone he had never met. With the local newspaper in his hand, he approached my mother in the kitchen and shared in Spanish the news on the passing of Pittsburgh Pirates right fielder Roberto Clemente.

Playing with one of my holiday gifts (a table hockey set) in the living room, I overheard their conversation. Not necessarily understanding what just occurred, I headed to their bedroom. With the door slightly ajar, I peeked inside to see my father, still holding the newspaper, crying.

Although I never saw Clemente play, my dad, who emigrated from Puerto Rico in the early 1950s, took my brother and me to Shea Stadium in 1974. My only recollections of that first-ever visit, besides traveling from the South Bronx to Flushing, Queens, on the No. 7 train, were eating Milk Duds and getting a splinter in my left hand from the stadium seat.

I have no clue who won that ballgame, but eating my favorite chocolate-covered caramel snack kept me content. I do recall that tingling sensation in my hand, and it wasn’t from a foul ball. Nevertheless, how cool that would have been to have caught a baseball or even interact with my favorite players.

But 50 years ago, Todd Radom did catch a glimpse of Clemente, one of the all-time greatest Major League ballplayers, a player whom my father adored.

Pirates Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Although only seven years old, Radom, a New York native, grew up to become a Red Sox fan, a vintage sports jersey enthusiast and, most importantly, a renowned graphic designer within the professional sports industry.

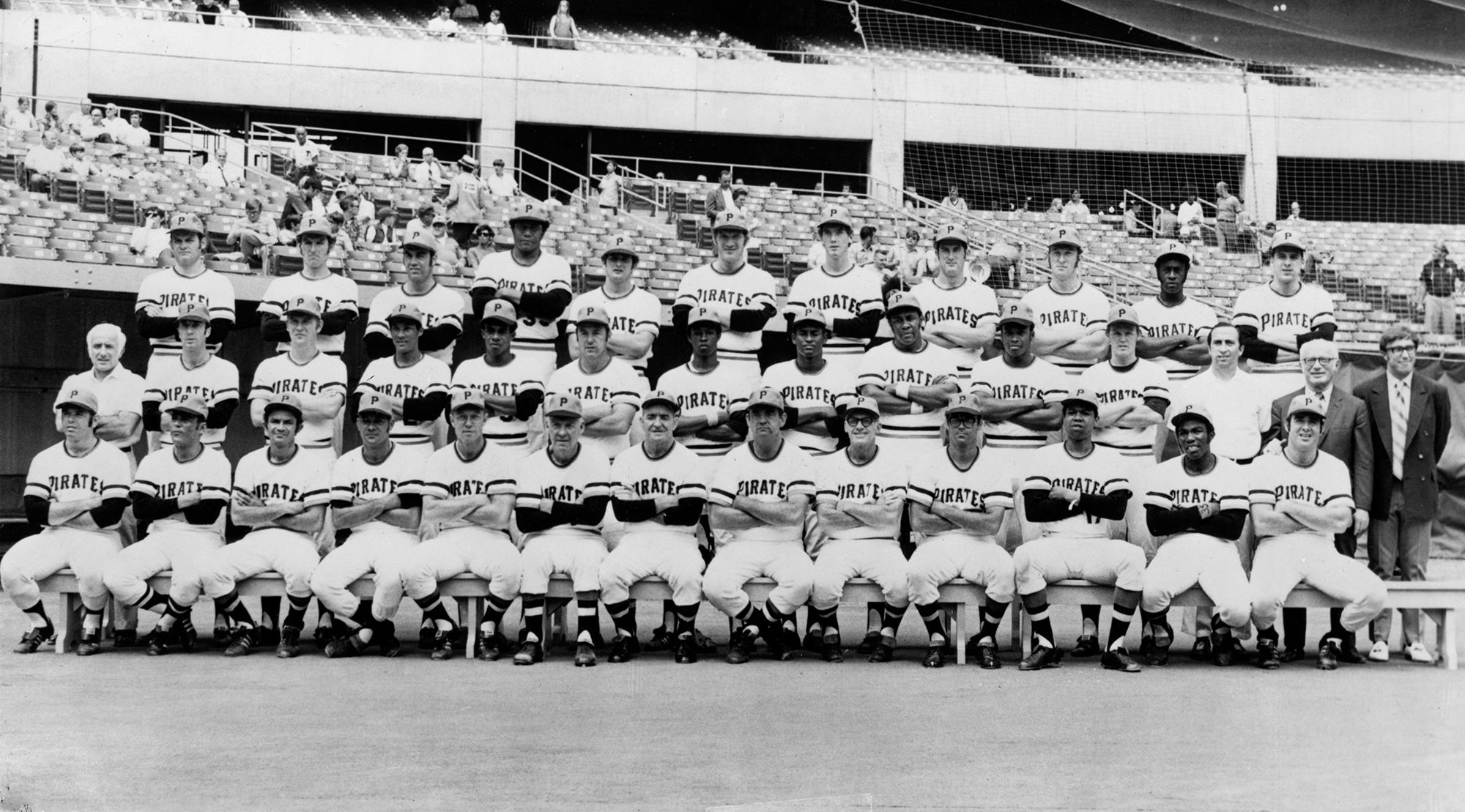

He would never have imagined his first baseball game on Sept. 24, 1971, at Shea Stadium would leave such an indelible mark on his life. In front of 35,936 fans, Radom watched the Pirates beat the Mets 3-2 in just under two hours. Within a month, the Pirates went on to win the World Series and the World Series MVP would be Clemente.

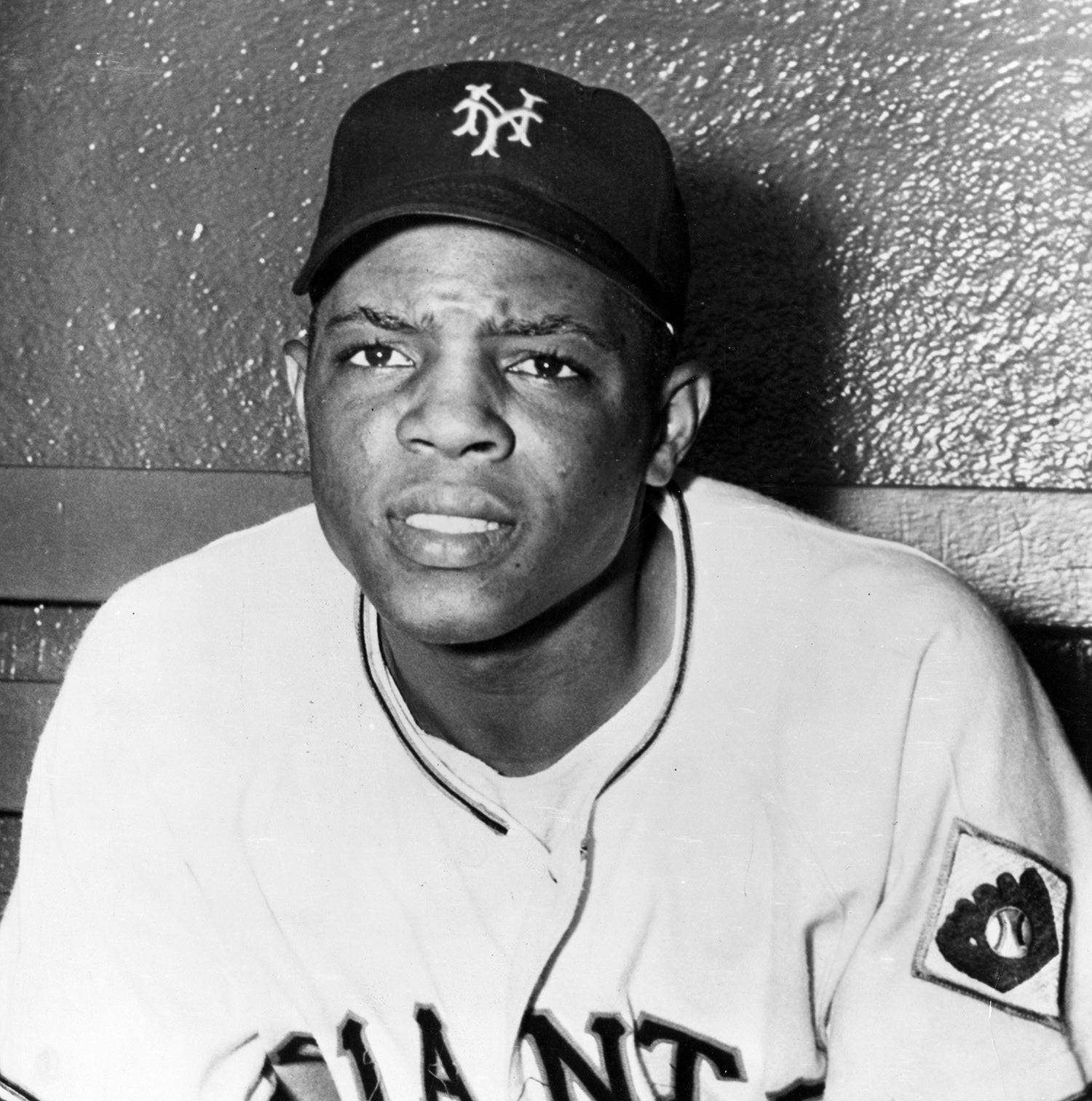

Clemente was the honoree that night in a pre-game ceremony at Shea Stadium. With his beloved wife, three sons and parents in attendance, he stood proudly alongside a contingent of Puerto Rican civic and community leaders from the New York area.

“Our baseball memories usually involve the green of the field, size of the stadium, the food and trip back and forth to the ballgame. But for me, my first baseball memories are of Roberto Clemente Night,” said Radom about that unforgettable evening.

His abiding memory of that night, through the eyes of a 7-year-old, was the center field gate that opened and the car that drove around the warning track to home plate.

“Sitting in the press box and I thought to myself, ‘Boy, this guy who they're giving this [car] to must be pretty important,’” said Radom, who credited his great uncle Gus for getting exclusive seats to watch this memorable ceremony. “There’s a lot of baseball players, but only one guy is getting a car. It was a very defined memory.”

Although Radom’s first indoctrination to this revered pastime was quite impactful, he could always count on his great uncle for a ticket to a Mets game.

From when the Pirates came to Shea years later, Radom can recall an Old-Timers’ Day game at Shea, where he saw Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, Duke Snider and Joe DiMaggio.

“It was four days after the Great Blackout of 1977,” Radom said. “I’m 13 years old, and those black-and-gold uniforms made such an impression on me. I came from a family of artists and looked at the game from a different lens.”

“Observing those uniforms on the field during the 1970s and for younger fans of that day, the Pittsburgh Pirates were a baseball powerhouse.”

For over 30 years, Radom’s digital creations (specifically logos) have appeared on numerous MLB on-field apparel/merchandise. As an artist, he collaborates with clients to help create their visual identity, and his distinctive work can be found not only within the big leagues but throughout the professional sports landscape.

Twenty years ago, Major League Baseball unveiled its newest logo — it depicts a ballplayer cast in metallic bronze — in recognition of community service, an award given annually to ballplayers. The honor was dedicated to Clemente, a humanitarian who made an impression on a young boy at Shea Stadium 50 years ago.

The graphic artist who designed the eye-catching black-and-gold logo was Todd Radom.

From the summer of 2007, I can recall speaking in Spanish with the late Vera Zabala, Clemente’s widow, about that momentous occasion in New York City where her husband was honored at Shea Stadium. Vera, whom I knew very well, was also the Goodwill Ambassador for Major League Baseball.

“Prominent Latinos from the New York area helped organize and attended the event, including representatives from the Mayor’s Office, and Herman Badillo from the House of Representatives,” said Zabala, recounting those memories in our phone conversation. “They presented Roberto with a Cadillac Eldorado convertible. He was very emotional and appreciative of what the community did for him.”

Of all the accolades the Hall of Famer received during his baseball career, the heartwarming weekend, dubbed “Superstar — Roberto Clemente,” on Sept. 24-25, 1971, touched his heart, she said.

These celebratory festivities included an opening reception at LaGuardia Airport and a press conference at the Hotel Commodore. Before the Pirates-Mets game Friday night, community organizers held a pre-game ceremony in Clemente’s honor. The following evening, a dinner/dance inside the Grand Ballroom of the defunct hotel capped the weekend.

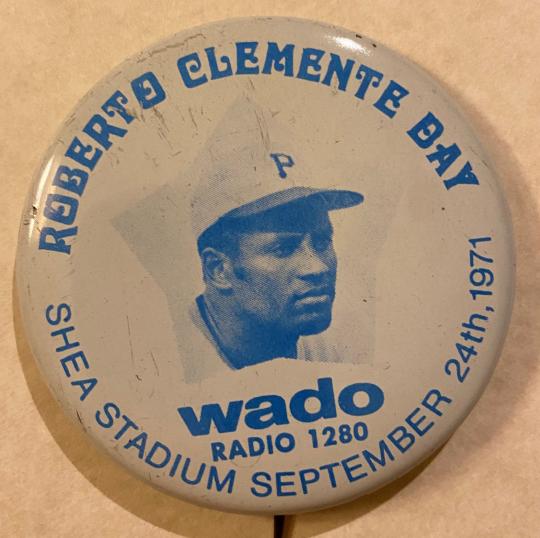

One of the mementos I possess from that historic game was a circular lapel pin with Clemente’s image and WADO 1280 AM, the Spanish radio station sponsor displayed on the front and distributed to fans.

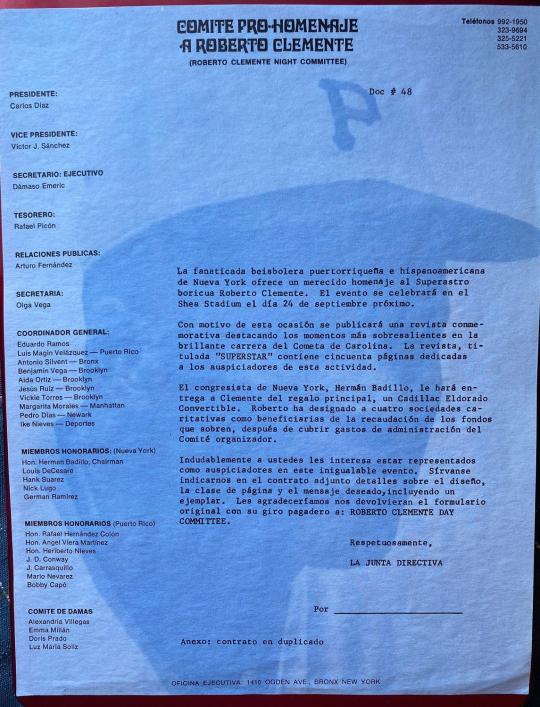

Throughout my research, I acquired another artifact: light blue stationery with a close-up of Clemente’s face on the paper and these bold words written in Spanish:

Comite Pro-Homenaje A Roberto Clemente (Translation: Roberto Clemente Tribute Committee).

Also on the stationery in Spanish was a typed letter addressed to potential sponsors in Puerto Rico and throughout New York City soliciting financial support for a commemorative journal, titled “Superstar.”

Recently, I had an opportunity to see select digital images of the “Superstar” dinner journal, courtesy of Scott Liedtke, an avid Clemente collector who lives in Chicago. Liedtke said the journal is extremely rare, and the one he owns is signed by Clemente on the cover. Not only did I see a number of creatively designed full- and half-page ads from various businesses, but inside the journal were a number of essays about Clemente's career in the big leagues.

Beautifully written by Don Kowet and interwoven throughout the pages of the journal were selective essays titled “The Man,” “Super Bat,” “Super Glove,” “Super Spikes,” “The Years Past,” and “The Will to Succeed.”

But it was the essay “The Years Ahead” that caught my attention. Kowet meticulously chronicled Clemente’s baseball journey in the 1970s and speculated on his future if not for the tragedy off the shores of Puerto Rico in 1972.

Clemente wasn’t just a visiting player. For the entire Puerto Rican and Latin-American diaspora, scattered throughout the five boroughs of New York City, they wanted to honor one of their own; to celebrate their “superstar,” affectionately called “The Great One” in Pittsburgh, who embodied philanthropy on and off the field.

Before the pregame ceremony and dinner/dance, Herman Badillo, a trailblazer in Latino politics who died in 2014, was selected as an honorary member of the Roberto Clemente Tribute Night committee where their office was based in the Bronx.

Badillo, a native of Caguas, P.R., became the first Puerto Rican borough president of the Bronx. In 1970, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives thus becoming the first Puerto Rican born congressman who proudly represented the South Bronx.

Gail Badillo, Herman’s widow, shared stories about her husband’s voracious appetite for reading. She said he was an avid outdoorsman who also competed in numerous New York City marathons. The couple also enjoyed trips to Yankee Stadium.

She said he was orphaned at an early age, received little guidance from relatives and couldn’t speak English. She recalled a life-changing moment when the editor of his high school newspaper took an interest in the future congressman. The editor recommended that Herman apply to City College of New York, which at that time was free for city residents. After earning his undergraduate degree, he enrolled in Brooklyn Law School and graduated summa cum laude.

During the pre-game ceremony at Shea, her husband welcomed Clemente to Queens and, along with other Puerto Rican community organizers, presented him with the Cadillac Eldorado. Before this two-day affair, Clemente designated four charities as the beneficiaries from the sponsorships/money collected during his weekend stay.

Throughout his political career, Badillo championed numerous causes, but when I asked Gail Badillo what she believed should be his lasting legacy, I wasn’t surprised by her response.

“His crowning achievement was his emphasis on education, because it came from his personal experience,” she told me. “He once said, ‘If we fail in education, we fail everywhere. It has to be our most urgent priority. Education was and is my crusade.’”

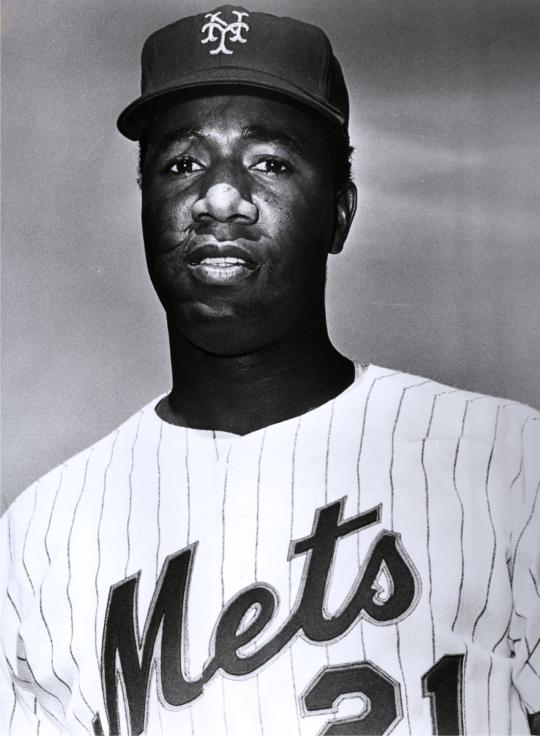

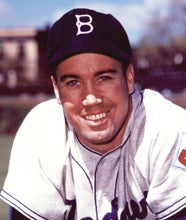

During that regular season game against the Pirates in 1971, a popular Mets’ outfielder from Alabama was in the lineup. Two years earlier at Shea, he caught the final out in the 1969 World Series to catapult his “Miracle Mets” to their first championship.

Cleon Jones, who like Clemente wore number 21, admired and watched his exploits from afar. He was in complete awe of how Clemente carried himself throughout his phenomenal career.

“There was Willie Mays, Hank Aaron and Roberto Clemente,” said Jones, who was in left field when Clemente’s eighth-inning double scored Gene Clines to provide the difference in Pittsburgh’s 3-2 win that September night. “And not necessarily in that order and depending [on] who you’re pulling for. There were those three in the National League and then there was everyone else.”

He said the three greats “created their own fanfare.”

Jones remarked how he wanted no part of wearing those legendary numbers.

“I really wanted number 22 because that was my number in high school,” Jones said. “When I was given number 21, the player that came to mind was Roberto. You just wanted to try to live up to that number because you can certainly try to live up to his standards.”

Danny Torres is a freelance writer from the Bronx, N.Y. and the host of the Talkin’ 21 podcast