- Home

- Our Stories

- In 1972, the Athletics launched a dynasty

In 1972, the Athletics launched a dynasty

Imagine the Cincinnati Reds from 50 years ago: clean-cut, no beards, no mustaches, no facial hair whatsoever. The team banned whiskers of any kind.

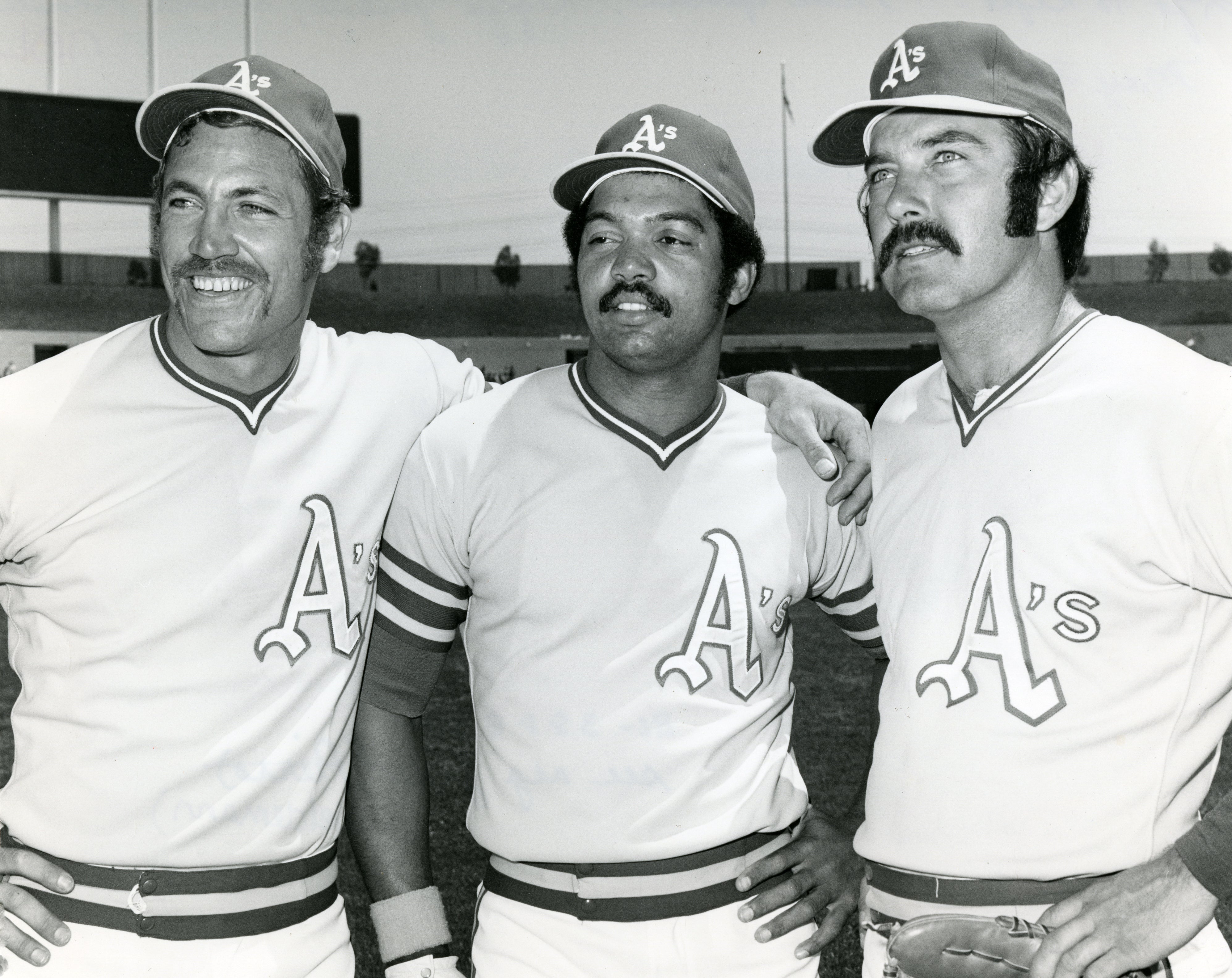

Now imagine the Oakland A’s from that time. Not only was facial hair accepted, it was encouraged to the extent that anyone who grew it out would receive a bonus.

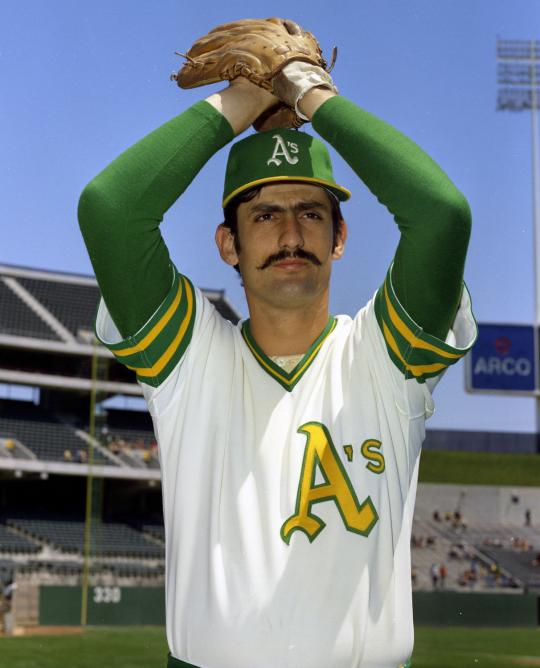

“There really was no facial hair anywhere in the big leagues,” Hall of Fame relief pitcher Rollie Fingers said. “We were a bunch of crazies from Oakland. We broke the mold back in ’72.”

True on multiple fronts. Not only did the A’s let their hair flow, they let their game flow, and their game was the best in the business. They are the only team in history, besides the Yankees, with three consecutive World Series championships, and it all started in 1972, when the A’s took down the mighty (and clean-shaven) Reds in seven games.

Athletics Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Fifty years later, all teams have players with various amounts of facial hair. It’s accepted. It’s embraced. Back in 1972, it was groundbreaking, and the A’s led the way in fashion and on the field.

In their fifth year in Oakland, following their move from Kansas City, the A’s shocked the baseball world with a fun-loving cast of characters that largely came up through the ranks together and wore bright green and gold uniforms with white spikes.

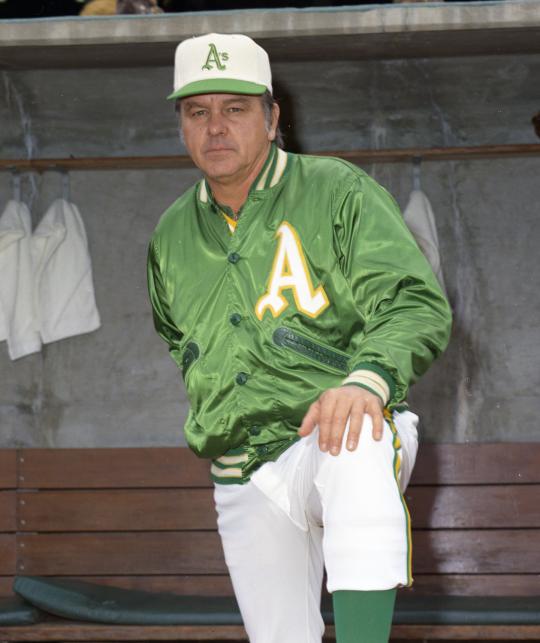

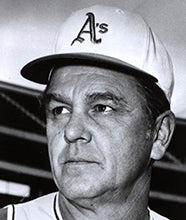

Managed by Hall of Famer Dick Williams, the A’s were known for fighting off the field and jelling on it – united in their disdain for frugal owner Charlie Finley — and they did their best work in the World Series, when, year-by-year, they took down the Reds, Mets and Dodgers, respectively.

“I don’t know where the years went, but they flew by,” said Gene Tenace, MVP of the 1972 World Series.

“My mind goes back to what a great ball club we had. You don’t appreciate it as much when you’re playing, but we had everything a manager could want, every phase of the game. We could hit the ball over the fence, we could manufacture runs, we had great pitching, we could execute fundamentals with anybody.”

Sal Bando, Oakland’s third baseman and captain during the dynasty, said, “Time goes quickly; what can I say. There are some great players who never got to one World Series, let alone won one, and we won three in a row.”

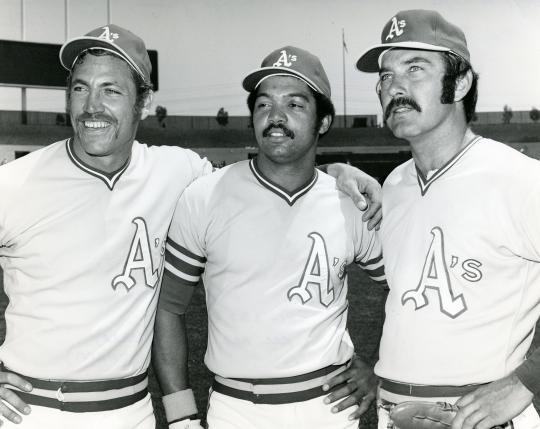

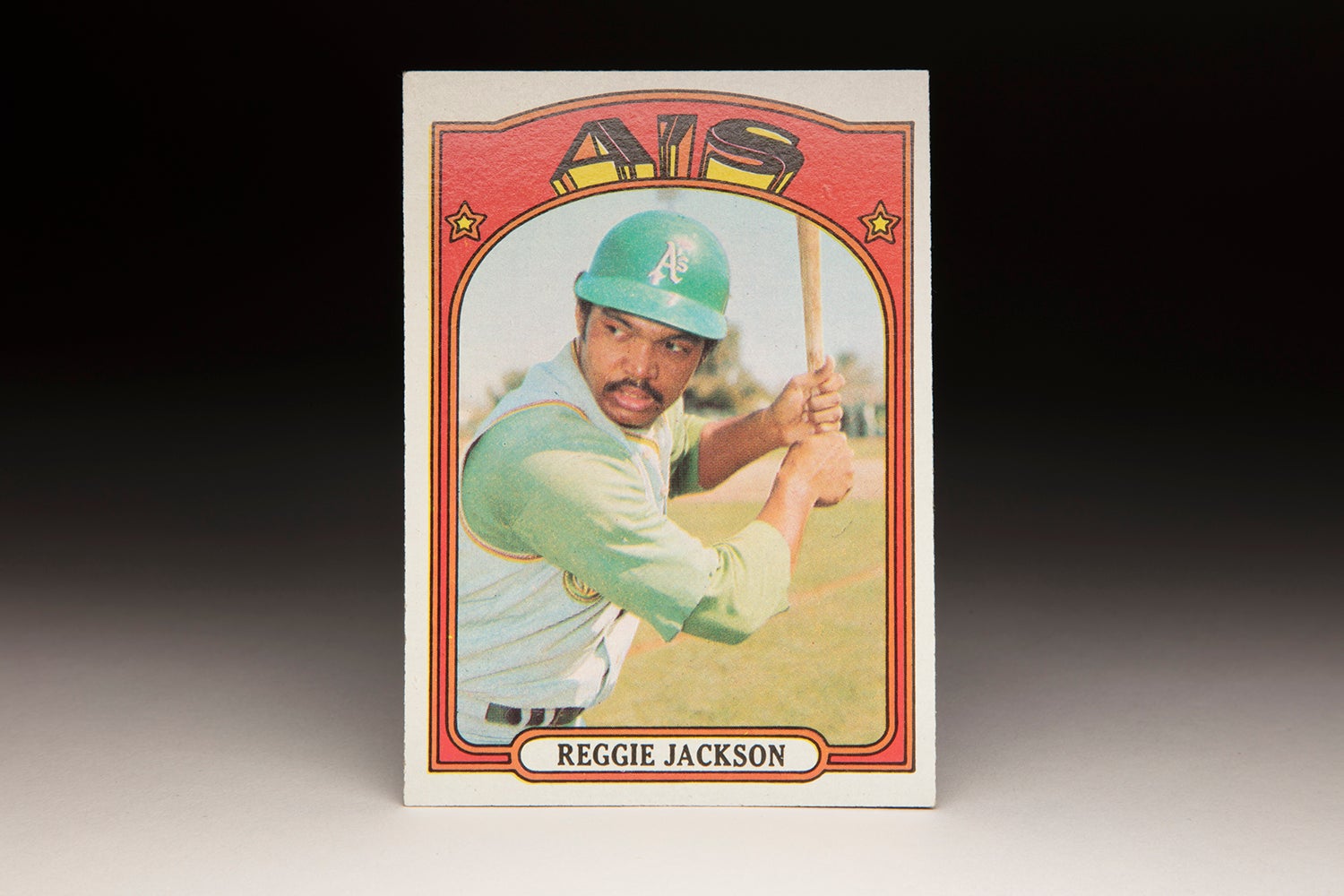

The core of those teams was the same throughout the three-year run and featured Hall of Famers Catfish Hunter, Reggie Jackson and Fingers, along with an impressive complement of pitchers (Vida Blue, Ken Holtzman and Blue Moon Odom) and position players (Joe Rudi, Bert Campaneris and Bando).

The run of success actually began in 1971, when the upstart A’s won the American League West but were swept by the Orioles in the AL Championship Series. After that season, the A’s acquired the left-handed Holtzman in a trade that sent outfielder Rick Monday to the Cubs, and the rotation was solidified.

The 1972 season was delayed slightly because of a players’ strike, but the A’s didn’t miss a beat. They won their opener in 11 innings in walk-off fashion, raced to a 33-13 start and won the division by 5½ games over the White Sox.

As the story goes, Jackson provided a sign of things to come when he grew a mustache, much to the chagrin of the baseball establishment and many in his own clubhouse. What transpired helped define the culture and mindset of a team that became known as the Mustache Gang.

“Everyone wanted Reggie to shave it off, and he wouldn’t do it,” Fingers said. “So four of us pitchers – me, Catfish, Darold Knowles and Bob Locker — decided we’d start growing mustaches. We figured if we did, Dick Williams would say, ‘OK, guys, shave off the mustaches,’ which meant Reggie would have to shave his off.”

The move backfired. Finley, while considered a cheap owner, was a skillful salesman. Ban facial hair? He did the opposite – which wasn’t unusual for Finley.

Any player growing a mustache would receive a $300 bonus, Finley announced. This was a momentous development, considering ballplayers hadn’t been seen with facial hair for decades.

“That was goofy Charlie. For 300 bucks back then, guys would grow mustaches on their (behinds). So we all grew mustaches,” said Fingers, who took his growth to a different level and sported a handlebar mustache, which he still has today.

A year after the Orioles eliminated Oakland in the playoffs, the A’s beat the Tigers in the ALCS to reach their first World Series since 1931, back when they were the Philadelphia A’s.

The 69th World Series pitted a team demonstrating its follicle freedom against a team that was straight-laced and well-groomed. The Hairs versus the Squares, as the matchup was known.

“It just caught on,” Bando said of the facial hair. “It was kind of a symbol. It was a good distraction from the pressure. You went with the flow. The Reds walked with stiff legs, and we were a little more flexible. It was fun being the dark horse. We were underdogs all seven games.”

The Big Red Machine, which didn’t capture its first World Series until Oakland’s run ended, were nonetheless a powerhouse in 1972, Joe Morgan’s first year in Cincinnati. In the NLCS, the Reds beat the Pirates, the 1971 champs, and entered the World Series as heavy favorites.

While Johnny Bench had an MLB-best 40 homers and 125 RBI, nobody on the A’s had as many as 30 homers or 80 RBI. Pete Rose led the majors in hits; Morgan led in runs.

The odds were tipped further in the Reds’ favor after Jackson seriously injured his hamstring stealing home in the final game of the ALCS, forcing him onto crutches and out of the World Series.

However, the A’s shut down the Reds’ high-powered offense, winning the first two games in Cincinnati by scores of 3-2 and 2-1.

The A’s grabbed another one-run decision in Game 4, Ángel Mangual’s walk-off single securing a 3-2 victory. That also was the score in Game 7, as Fingers’ two-inning save sealed the deal, the first championship for a Bay Area professional sports team.

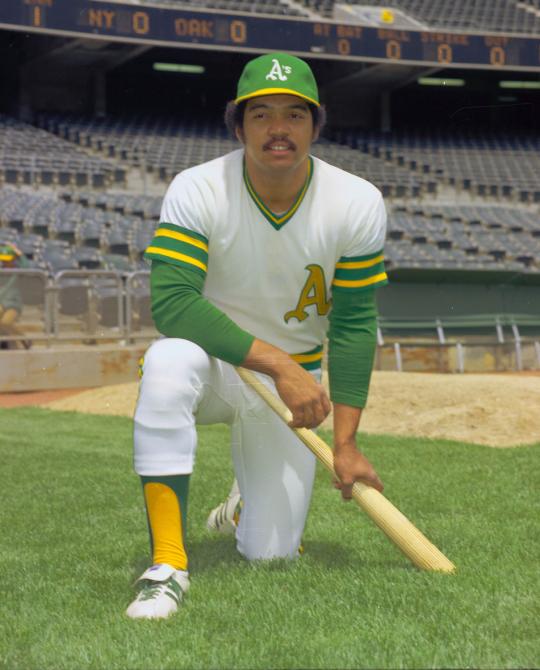

Tenace, who backed up catcher Dave Duncan until taking over the starting job in August, homered just five times in the regular season, but crushed a stunning four homers in the World Series, including two in Game 1 in his first two at-bats off Gary Nolan. He also homered in the Game 4 win and had two hits and two RBI in Game 7.

Tenace drove in nine runs, eight more than anyone else on his team, and was an easy choice for World Series MVP. His presence made Jackson’s absence easier to take. Jackson wound up the MVP of the 1973 Series and Fingers won the award in ’74.

With six of seven games decided by one run, Oakland needed to play stellar defense in the ’72 World Series, and the A’s produced a healthy share of highlights – two in the final inning of Game 2, in fact.

First, Rudi made a running, leaping, backhanded catch at the left-field wall to rob Denis Menke of a run-scoring double, and Mike Hegan, after entering as a defensive replacement, made a diving stop of César Gerónimo’s hard-hit ball.

One of the Series’ most memorable moments came in Game 3 after what had appeared to be a routine mound visit. In the top of the eighth, Bobby Tolan stole second, giving the Reds two runners in scoring position. Williams walked to the mound.

With first base open, everyone thought Fingers would intentionally walk Bench with a 3-2 count – especially after Williams motioned to first base while chatting with Fingers, Tenace and Bando. Tenace took his spot behind the plate and stood up to signify ball four was coming.

It never came. At the last moment, Tenace got down in a squat, and Fingers threw a slider on the outside corner that Bench looked at for strike three.

“We never practiced this particular play, never discussed it,” Tenace said. “Dick came out and in 30 seconds put in the play and walked away. It happened so fast. Morgan was yelling at Bench. Bench was peeking back at me. By the time Bench got focused on Rollie, the pitch was already there.”

Fingers said: “This is not Little League. This is a World Series game. Gene, Sal and I are looking at each other, ‘Hope this works.’ I couldn’t have thrown a better slider.”

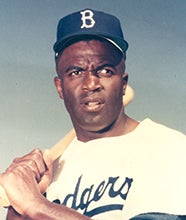

This World Series also is remembered for Jackie Robinson’s final public appearance, on the 25th anniversary of him breaking baseball’s color barrier. Robinson threw the ceremonial first pitch before Game 2 and offered powerful words to the crowd, calling for MLB to give an African American an opportunity to manage.

Nine days later, Robinson died. In 1975, baseball finally had a Black manager; Frank Robinson was at the helm in Cleveland.

“I was in the dugout when Jackie made that statement,” Tenace said. “After the game, they brought him to the visitors’ clubhouse. He came to my locker and congratulated me. So I’m standing at my locker with Mr. Jackie Robinson. You gotta be kidding me. What about the day I was having?”

John Shea, national baseball writer at the San Francisco Chronicle, has covered baseball for four decades and is co-author with Willie Mays of The New York Times bestseller "24: Life Stories and Lessons from the Say Hey Kid" and with Rickey Henderson on his autobiography "Off Base: Confessions of a Thief."