- Home

- Our Stories

- Baseball's anthem began as Tin Pan Alley hit

Baseball's anthem began as Tin Pan Alley hit

What do Frank Sinatra, Liberace, Stan Musial, Harpo Marx, LL Cool J, Harry Caray and Carly Simon have in common? They’ve all recorded baseball’s anthem, “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” the third most frequently played song in American culture, after “Happy Birthday” and “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

“Take Me Out to the Ball Game” was written – probably in about a half an hour – in the spring of 1908, by two gentlemen who were professional Tin Pan Alley songwriters and who professed never to have seen a big league baseball game.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

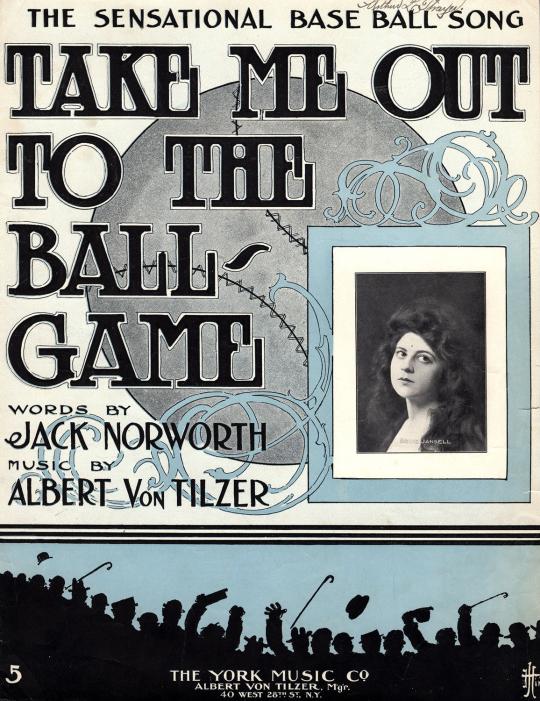

That claim was probably true for Albert Von Tilzer, a songwriter and publisher from Indiana who moved to Gotham to seek his fortune – and found it. He wrote more than 20 songs which sold over a million copies each and was astute enough to also start a publishing company with his brother that administered those songs. Von Tilzer was also the first to publish compositions by a couple of fellows named Irving Berlin and George Gershwin.

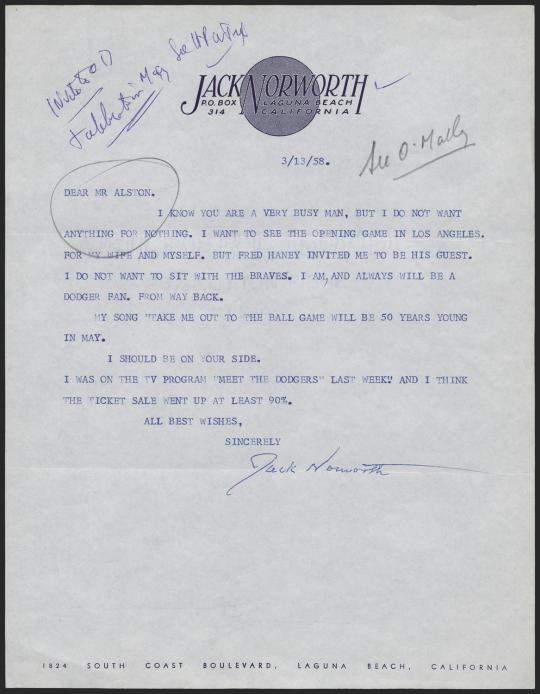

His collaborator on the song, Jack Norworth, hailed from Philadelphia, Pa., and was a multi-talented entertainer; he could sing, write, and act on stage, radio, television and movies. Norworth and his wife, singer-actress Nora Bayes, were as famous in early 20th century America as any celebrity couple in today’s pantheon.

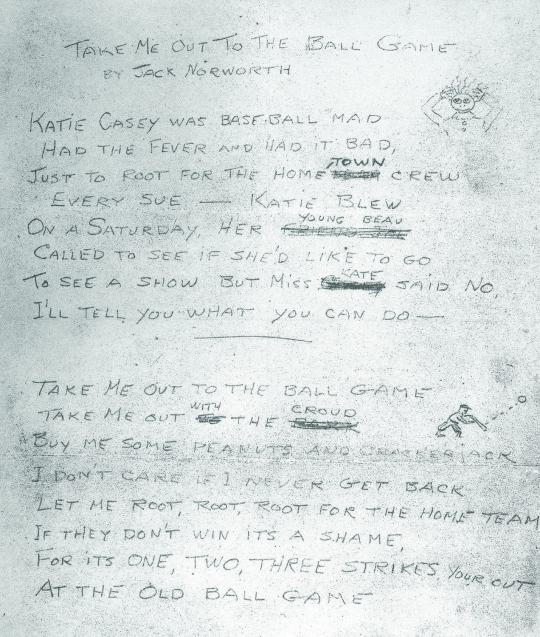

The story goes that Norworth penned the lyrics one day while riding one of Manhattan’s new subway trains north toward the Polo Grounds. He remembered seeing a sign advertising that day’s game and pulling out a pencil and paper to scribble down a set of lyrics, which Von Tilzer would later pair with a tune he had composed. The original manuscript is part of the Hall of Fame Library’s collection.

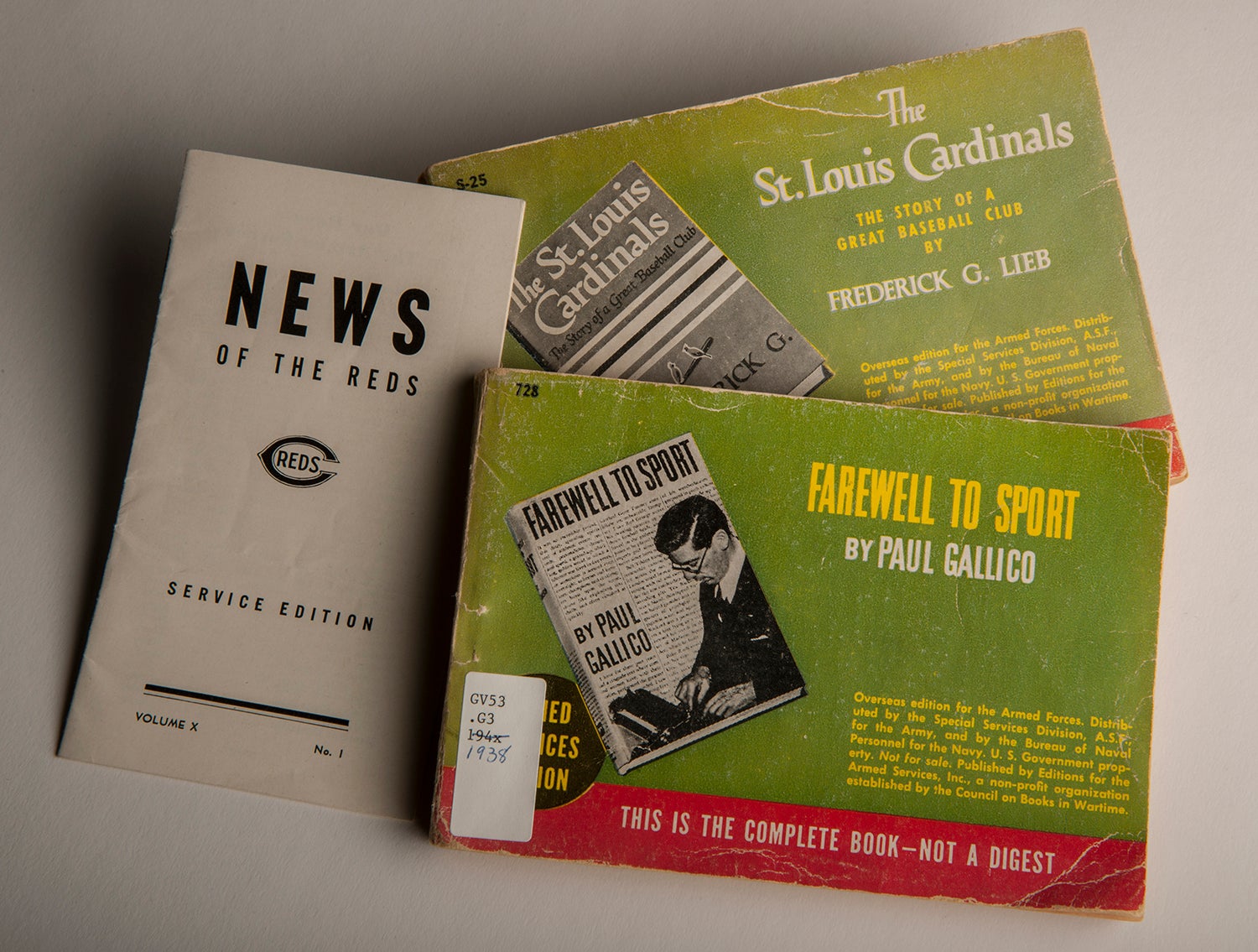

The song was not immediately popular at ballparks, surprisingly enough. In fact, the first known time it was performed in a ballpark was in 1934, almost 30 years after it was written. But it was a big hit in 1908, selling millions of copies of sheet music and “Edison Wax Cylinder” recordings. Its initial popularity was due to a set of “lantern slides” shot at the Polo Grounds to promote the song. The slides tell the story of Katie Casey, the fictional protagonist of the songs’ two rarely-heard verses, who implores her beau to take her out to the ball game.

The lantern slides were shown at movie theaters during intermissions when the projectionist changed the film reels, which usually took three or four minutes. The house pianist would play a song and the projector would flash the illustrated scenes, while encouraging the audience to sing along. If a song were popular at the movie houses, it would translate into sales of sheet music and recordings – and indeed, three different artists scored top 10 hits with the song from October to December of 1908.

The backdrop for the song’s initial success was certainly the great National League pennant race of 1908, involving the New York Giants, Chicago Cubs and Pittsburgh Pirates.

The AL also had a great race that year, won by the Detroit Tigers on the season’s final day. But the real hoopla was in the NL between the Cubs and Giants.

The teams had been bitter rivals since the 1880s, finished the season tied, and met in a dramatic tiebreaker, which the Cubs won in New York to advance to the World Series, where they would beat the Tigers.

Cubs shortstop Joe Tinker teamed with second baseman Johnny Evers not just on double plays but also on a short-lived musical partnership, which resulted in their writing and publishing a song of their own that November, called “Between You and Me.” It was one of dozens of baseball songs written in the wake of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” attempting to capitalize on the song’s popularity.

Immortal composer George M. Cohan also got in on the act, writing a song called “Take Your Girl to the Ball Game,” which flopped when compared to Norworth and Von Tilzer’s song. Complaining to Norworth, Cohan professed: “I didn’t write mine soon enough.”

“Or good enough,” Norworth shot back.

The first known playing of the song in a big league ballpark came during the 1934 World Series, when the St. Louis Cardinals band, led by Pepper Martin, played it on the field before a game.

But it would take Hall of Famer Bill Veeck and 1989 Ford C. Frick Award winner Harry Caray to bring the song to the levels of popularity it enjoys today.

“I tried it in Milwaukee, Cleveland, St. Louis and Chicago the first time, but it never worked,” Veeck said. “Finally I got the right guy. It does a lot for the game and gets the fans involved even if the Sox are losing.”

Veeck was referring to his recruitment of colorful Chicago White Sox announcer Caray, who began singing the song into a mike during the seventh inning stretch in 1976 – after Veeck either tricked him or leaned on him to sing live. Caray, already a legendary broadcaster for his work with the Cardinals from 1946 to 1969 before television and the Cubs elevated his national status, wanted no part of Veeck’s plan. It eventually became Caray’s signature moment when he jumped on the Red Line and moved on up to the North Side Cubs in 1982 – the Cubs nationwide cable contract spread the song like wildfire throughout the major and minor leagues.

Since Caray’s death in 1998, the Cubs have continued the tradition of singing the song at Wrigley Field during the stretch – using guest conductors such as Hall of Famers Ernie Banks and Billy Williams, as well as Cubs alumni. Players and alumni from Chicago’s other professional sports teams the Bears, Bulls and Blackhawks have also recited the song along with other notables such as Jay Leno, Chuck Berry, Kenny Rogers, Eddie Vedder, Ozzie Osbourne, Dennis Miller, John Fogerty, Julia Louis-Dreyfuss, John Cusack, Lou Rawls, Cyndi Lauper, Muhammed Ali, Bonnie Blair, George Will, Gale Sayers, Walter Payton and Mike Ditka, just to name a few.

The beloved baseball song is played somewhere 365 days of every year, as verified by data from the American Society of Composers, Authors and Producers. It has been covered by over 500 recording artists and used in television and the movies over 1,200 times.

Tim Wiles was the director of research for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum