Remembering the Cannon Street All-Stars

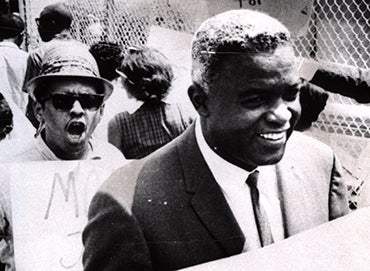

By 1955, Jackie Robinson had established himself as one of the game’s all-time great second basemen. A number of other Black players had followed him to the National and American leagues during that eight-year span that began with Robinson’s entry in 1947. The list of African American pioneers to debut during that time included Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks, Roy Campanella, Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, Willie Mays, Minnie Miñoso, and Don Newcombe, just to name a few.

Yet, at other levels of the game, all was not well. In some southern minor leagues, Jim Crow segregation persisted. And at the amateur levels, large pockets of discrimination prevented young Black players from participating in the game. One of the problem areas involved Little League Baseball, particularly in the South.

In 1955, Little League sanctioned only one southern-based league that featured Black players. That league was located in Charleston, S.C. In 1953, the YMCA had chartered that league, making it the first African American Little League in South Carolina’s history. Out of that league came a team called the Cannon Street All-Stars, located at the Cannon Street YMCA, who registered to compete in Charleston’s city-wide Little League tournament.

One of the 14 players on the team, John Rivers, remembers the atmosphere surrounding the Cannon Street team and the YMCA. “Well, it was a great community,” Rivers told historian Larry Lester during a 2023 oral history interview. “Of course, you understand it was under the laws of Jim Crow and segregation, but our neighborhood was very rich with love and care for one another.”

The Jim Crow realities of Charleston would soon come into play. Sixty-one other teams, all white, were scheduled to take part in the city tournament, but when they learned about the inclusion of the Cannon Street club, they all withdrew from the competition.

“Little League issued 62 charters to the state of South Carolina for leagues,” Rivers explained in his interview with Lester. “62 leagues. We were one of ’em. So 61 were all white and one was Black, and we were that charter, the Cannon Street Y. And we had all the rights and privileges under that charter.

“And Little League, when it started in 1937 I believe, they have in their bylaws and the rules, there's no segregation, no discrimination, all that stuff. So they had the same charter, but I guess they didn't realize the policy, Little League’s policy was no discrimination. So that’s kind of what opened the door for (Cannon Street YMCA president Robert) Morrison to enter us into playoff. And of course they wouldn’t play. They wouldn’t play us.”

With no other teams willing to participate, Cannon Street was declared the winner, by forfeit, of the city tournament.

In the meantime, the situation only hardened in Charleston. Although Little League Baseball, citing its own policy banning racial discrimination, had ordered the other teams to play in the city tournament, their managers and coaches had steadfastly refused. The team managers eventually seceded from Little League Baseball and chose to form their own segregated league. Eventually becoming known as Dixie Youth Baseball, that organization still exists, though its segregationist policy has long been abandoned.

As Rivers recalls, the Cannon Street All-Stars prepared to play in South Carolina’s state tournament, but opposition teams took the same approach as the opponents in Charleston.

“They’re like, oh no, it ain’t going to happen. Whites don’t play Blacks. So they walked out. So we won the state by default forfeiture. And the next stop was Rome, Ga., where the regional, Southeast regional was being played. And our coaches said, we'll go to Rome. And of course, Rome pulled the rule books out, and they found some paragraph in there that says a team cannot be seeded if they hadn’t played a game to advance to Rome. Well, we didn’t play a game, but it wasn’t our fault. It was a convenient way out of not seeding us.”

Little League President John McGovern tried to justify the ruling by saying that teams needed to win games on the field, and not advance by forfeit, in order to move on to regional play. That declaration officially ended the Cannon Street All-Stars’ season, thereby preventing the Charleston club from participating in the Little League World Series.

As part of a large public outcry, some members of the media railed against Little League Baseball. They included famed baseball writer Dick Young, who called for McGovern to resign his position as the head of Little League, citing his inability to follow his own organization’s ban against racial discrimination.

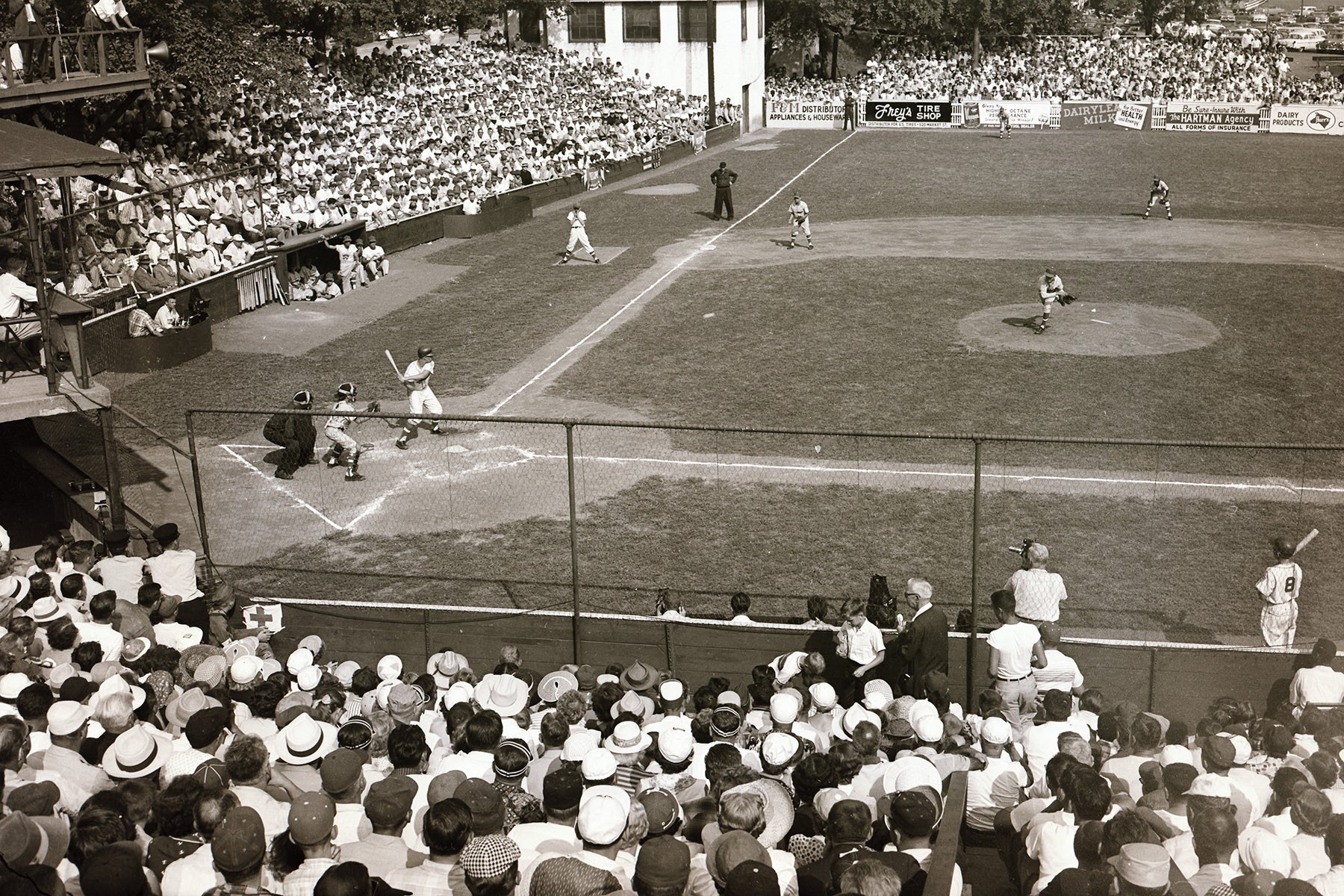

With a public relations disaster in the making, McGovern quickly came to regret his decision. Hoping to offer a partial remedy, he invited the Cannon Street All-Stars to come to Williamsport to watch the Little League World Series. (Expenses were paid by Cannon Street YMCA President Robert Morrison and civil rights leader Esau Jenkins.) Prior to the championship game, the Cannon Street team was allowed to practice on the field and was introduced by the public address announcer. Moments later, fans began to chant, “Let them play, let them play.” Instead, the Cannon Street All-Stars watched.

To make matters more frustrating, Little League’s governing body eventually declared that Cannon Street’s 1955 championship was not official and would not be formally recognized in Little League records.

According to Rivers, he and the other players chose not to talk much about the situation, but that did little to ease the pain of what they had to endure.

“So we didn’t talk about it. So it tells me how painful it was. We didn’t express anything about it… And we never blamed. We went on to other things. I went on and played two more years of Pony League baseball on segregated [teams], on the opposite side of town, and concentrated on my doing well in school. Those were the things that we did to compensate for that disappointment. And fortunately, it paid off for most of us. I think everybody did reasonably well. [Rivers himself became a successful architect.]

“What was also painful, and on a side note when this was happening, my dad was in Korea. He’s in the Army. He’s defending the United States of America in Korea… and he reads a clipping about his son back in America – the country that he’s fighting for – is not allowed to play baseball because [of] the color of his skin, that’s painful.”

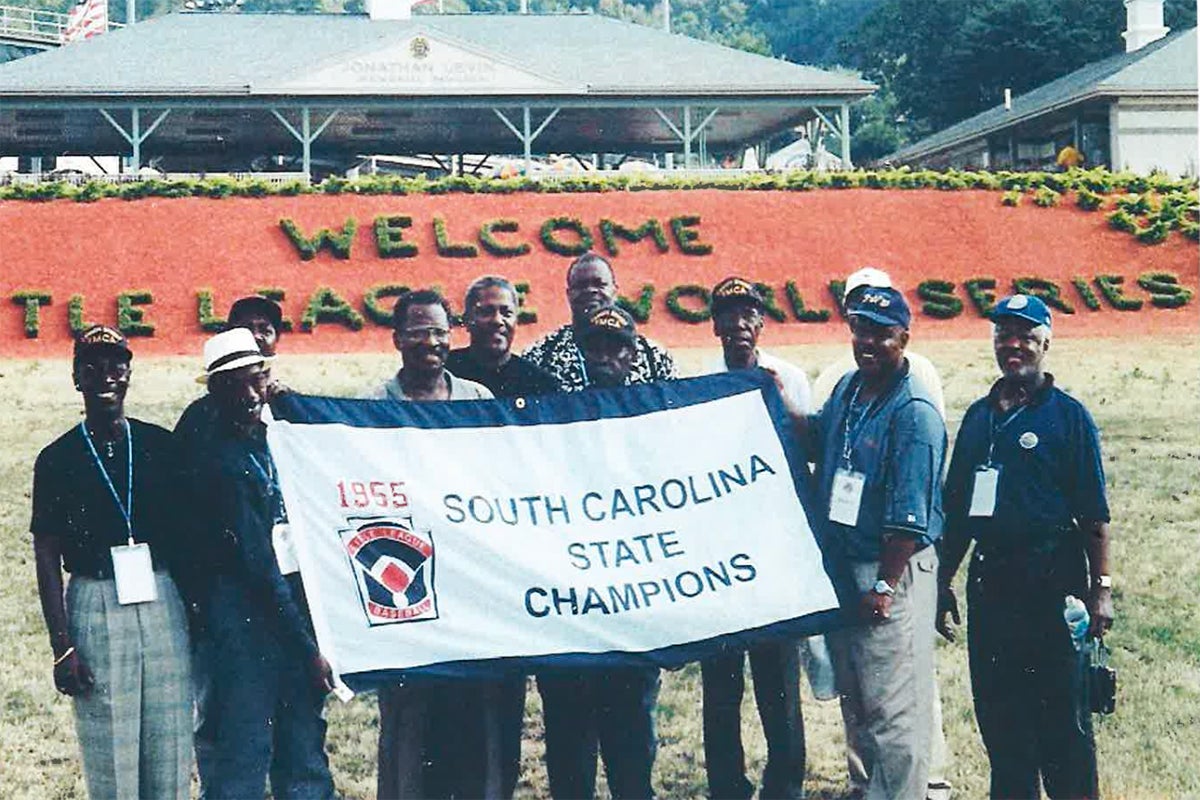

In 2002, Little League Baseball finally addressed the Cannon Street dispute by inviting the players from that team to Williamsport. There they were introduced to a crowd of fans and treated to a standing ovation. More importantly, the players received a championship banner recognizing their state title, which was now officially restored to the record books.

For many, the awarding of the banner and the correction of the records had come too late in the story, but they at least ensured that future generations would recognize an undeniable fact: The Cannon Street All-Stars, and no one else, had won the Little League championship for the state of South Carolina in 1955.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum