They also played: Black women in baseball

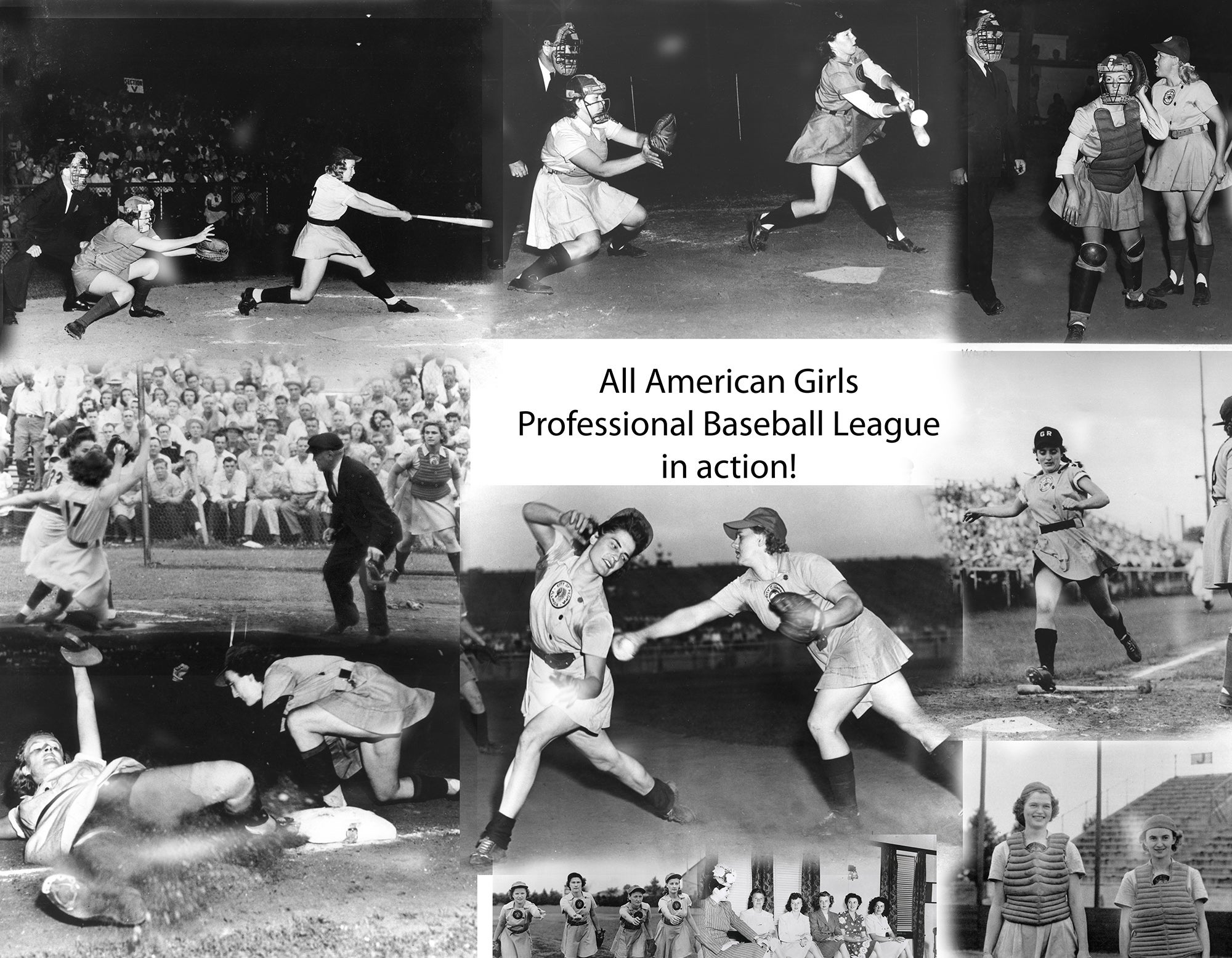

From 1943 to 1954, women played pro baseball in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. The opportunity came because of World War II and the need to provide entertainment on the home front.

The league could have ended when the war was over, but it did not. Instead, hundreds more women got to play baseball through the 1954 season. But one group of women who did not get to play in the AAGPBL were Black women. That denial did not prevent them from playing, however. They found their own place on the diamond.

STORIES OF BLACK BASEBALL

Stories that highlight the lives and experiences of Black ballplayers through key moments in history, artifacts and baseball cards.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

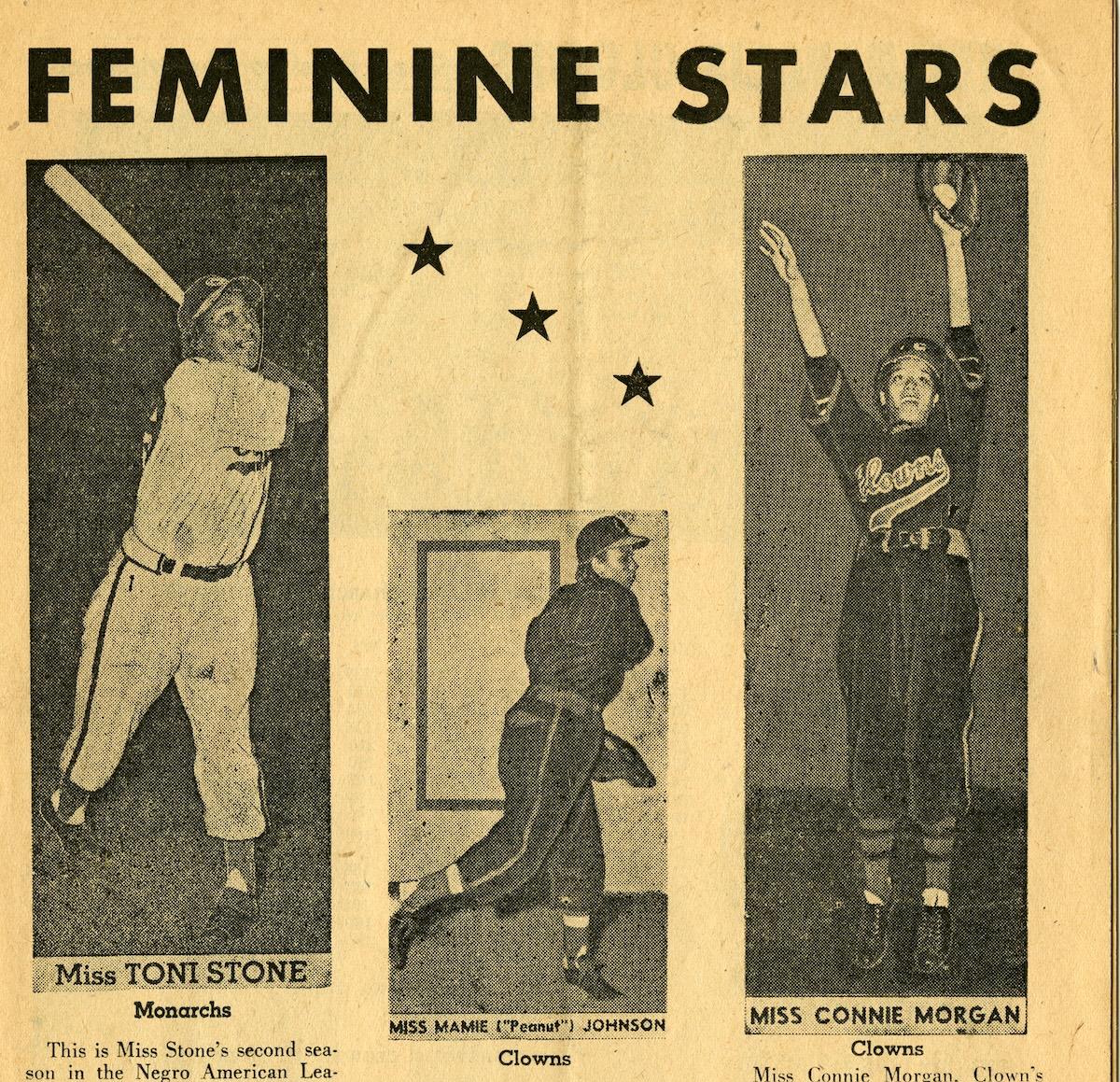

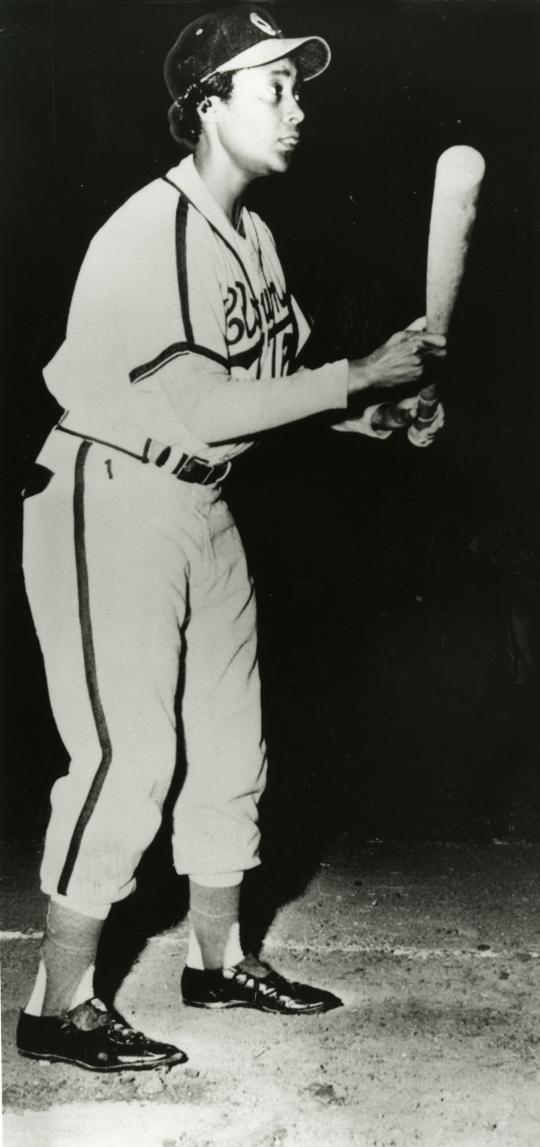

Three Black women played in the Negro Leagues in the 1950s: Toni Stone, Connie Morgan and Mamie Johnson. For most baseball fans, that is where the story begins and ends for Black women playing baseball, but that is not the full story. Black women have played the game from the sport’s earliest days. They played for fun and they played on organized teams, amateur to professional. Their story begins with the Dolly Vardens in the 1880s and continues to the present day with U.S. Women’s National Team player Naomi Ryan.

In 1883, newspapers started carrying stories of a team called the Dolly Vardens playing in the Philadelphia area. Reading these stories surprised many to discover the team was a roster of Black women. In fact, there were two Dolly Vardens teams playing around the city, and one of their opponents was another Black women’s team called Captain Jinks. Wearing their long skirts, colorful belts and caps, these ladies entertained fans with some high-scoring games that showed they were better hitters than fielders. Led by captain Ella Harris, the Dolly Vardens played a variety of local competition set up by organizer John Lang, though the results were rarely covered. Reporters tended to focus more on their attire and their gender than they did the actual games.

The St. Louis Black Bronchos, playing between 1910 and 1913, received better coverage than many of their earlier counterparts. The Black Bronchos traveled and played opponents throughout the Midwest. Under the direction of baseball promoter Conrad Kuebler, the Bronchos played from Tennessee to Oklahoma, drawing enough fans to encourage teams to continue to book them as a good game. One of their opponents was the Nashville Giants, whom they beat, 2-1, in a 13-inning game.

After a 9-9 road trip through Oklahoma in June 1911, the Bronchos headed to Texas that July, where they beat a team in Denison, 8-6, and two days later won, 3-2, in McKinney. A day later, the Bronchos prevailed, 6-3, in Mineral Wells.

Papers often advertised them as the “Only Female Negro Team on the Road.” This made them a novelty or curiosity for the fans — and sometimes for journalists who did not take them seriously. Still, several players stood out for their talent, such as Kitty McFadden, who received praise for her arm, and Nelly Carter, for her ability as a hitter and fielder. First baseman Leanna Wilson was credited with solid play in the field.

Scouring old newspapers reveals many Black women’s teams playing all over the country from the 1890s into the 1960s. There are even mentions of attempts to establish leagues in some areas of the country. In 1913, two girls’ teams in Arizona trained for over two months to play a charity game to raise money to help pay the debt of their African Methodist Episcopal church.

News accounts talk of the Sepia Stars heading to Canada to play the Burtons (a men’s club) in 1955. Acclaimed as the National Negro Women’s Champion in 1954, Babe Davis was credited with leading the club with a .450 average in 69 games. Their success made them a main attraction from the U.S. to Canada.

Discovering the stories of Black women who played baseball all over the country is a difficult task. Women’s baseball in general was never covered well, and it was even worse for Black women. Women were not supposed to be involved in sports like baseball since the game was meant for men. Women were only supposed to play softball. Sometimes teams were called baseball teams, but further research can often show the clubs were really playing softball, which complicates the efforts even more.

What we do know is the stories and names presented in this story are just the tip of the iceberg. There is so much more history to uncover to help fill out the story of women in baseball.

Leslie Heaphy is a curatorial consultant for the Hall of Fame’s ongoing Black Baseball Initiative.