- Home

- Our Stories

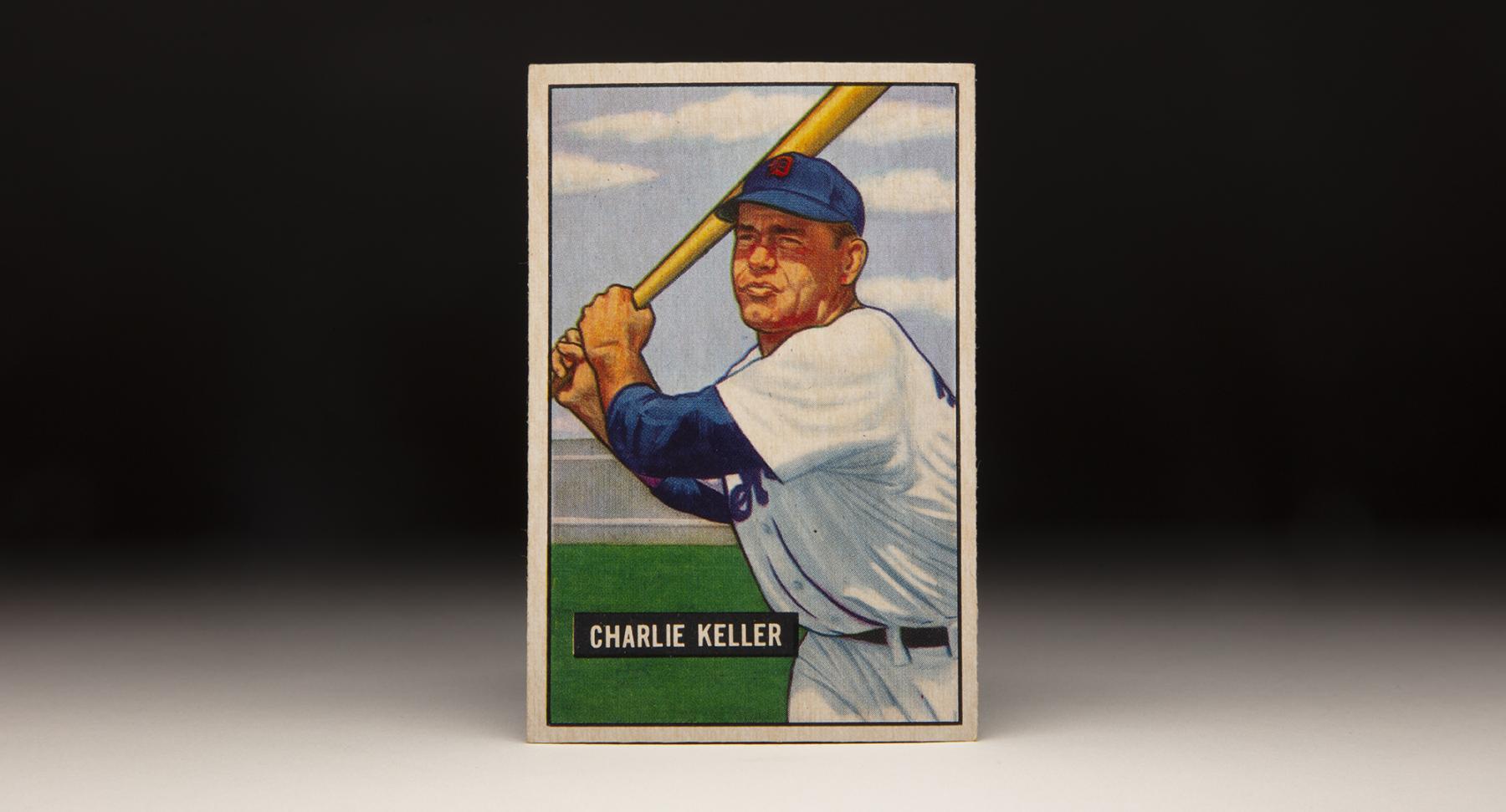

- #CardCorner: 1951 Bowman Charlie Keller

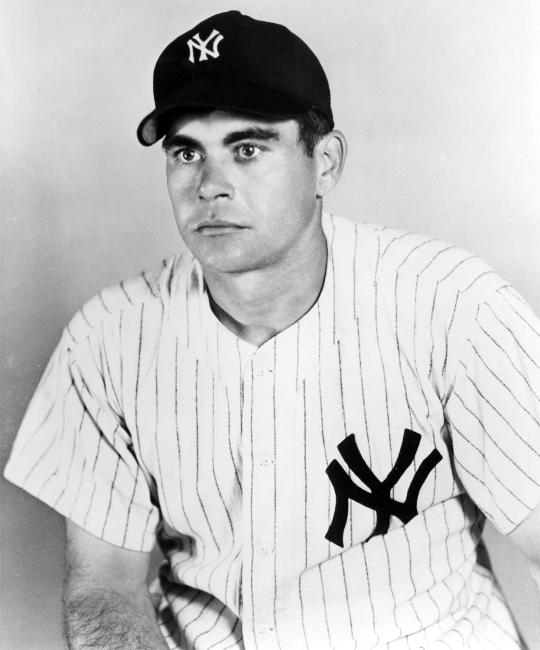

#CardCorner: 1951 Bowman Charlie Keller

In the hitting-depressed 1940s, Ted Williams and Stan Musial set standards for all others to follow.

Williams, for instance, had seven full seasons – each one that he played – of at least a .400 on-base percentage and a .500 slugging percentage. And Musial had five such campaigns.

Other future Hall of Famers, like Joe DiMaggio, Jimmie Foxx, Johnny Mize and Ralph Kiner had two similar campaigns.

Yankees Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

But the player who ranked third on that list with four seasons of a .400 OBP and .500 slugging percentage was a Yankees hero whose career was limited to six full seasons due to wartime service and injuries.

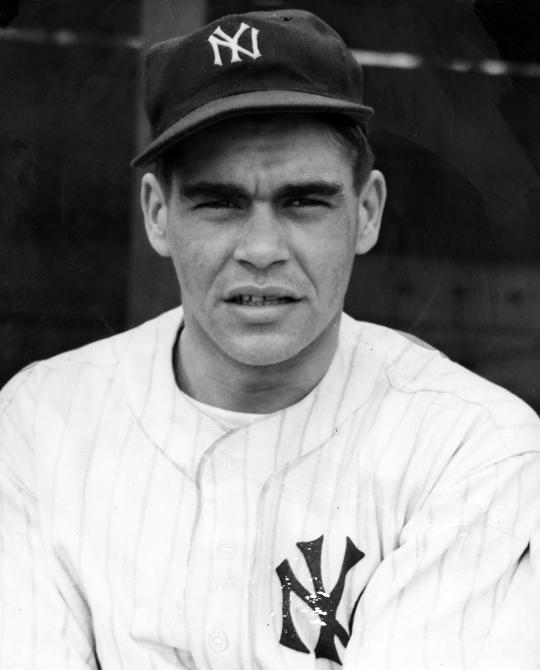

His name was Charlie Keller.

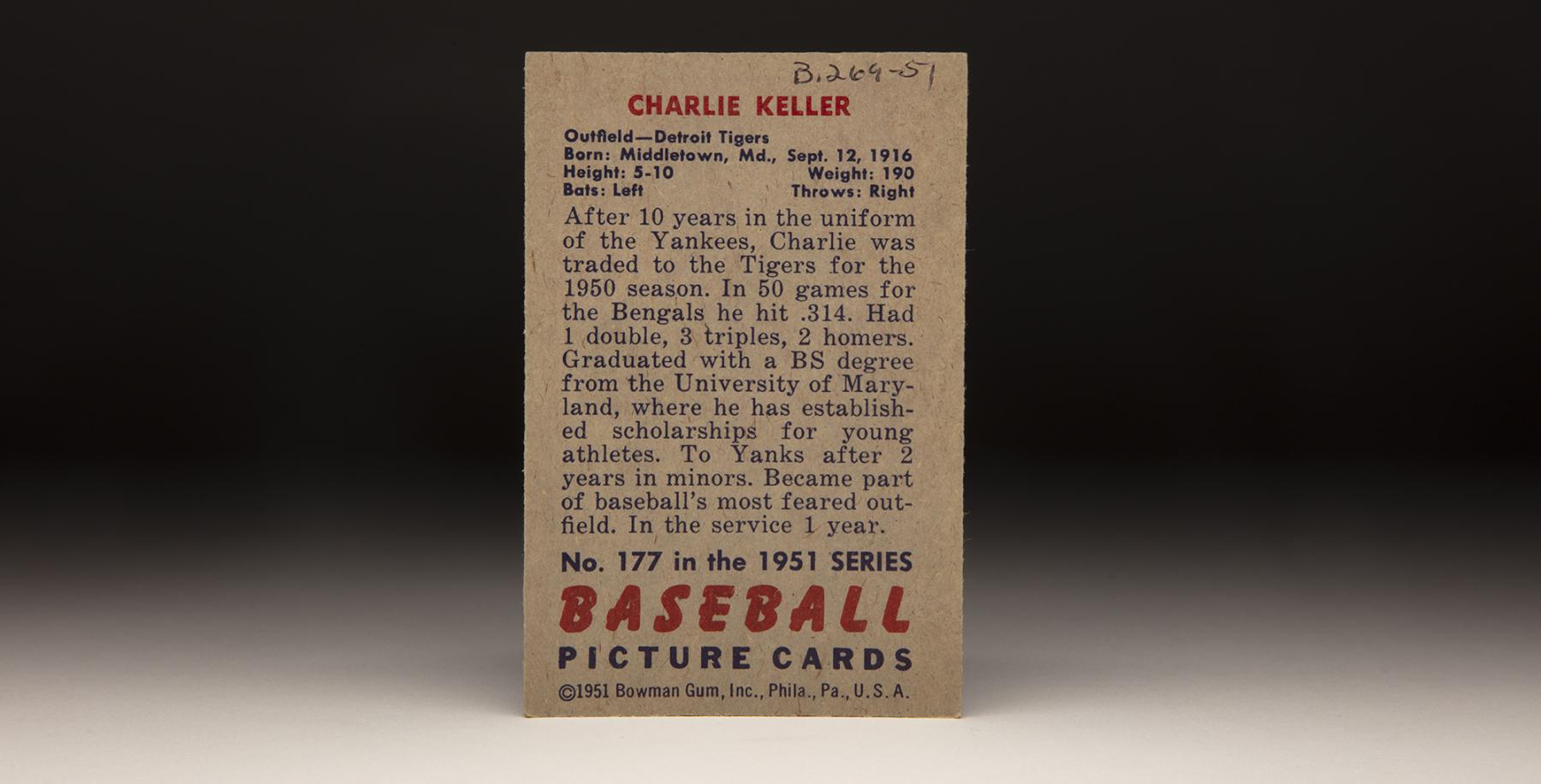

Born Sept. 12, 1916, in Middletown, Md. – about 55 miles northwest of Washington, D.C. – Keller was raised on a farm and excelled as a high school athlete. He earned an athletic scholarship to the University of Maryland following his high school graduation in 1933.

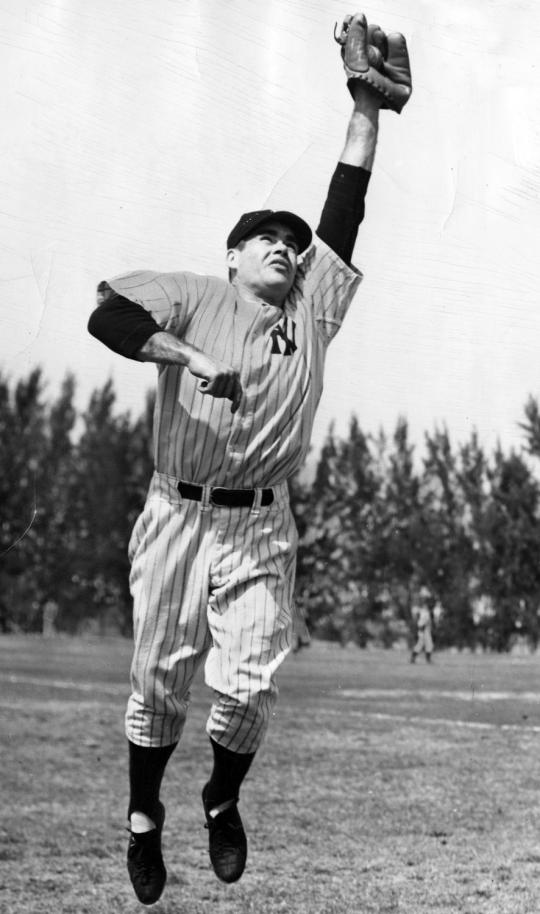

By 1935, he was starring for the Terrapins on the diamond as an outfielder before moving to shortstop the following season.

“I have seen many fine players in my time,” umpire Ed Brockman told the Baltimore Sun in 1935. “But Charlie Keller, University of Maryland center fielder, is by far the most promising I have come across in a long time.”

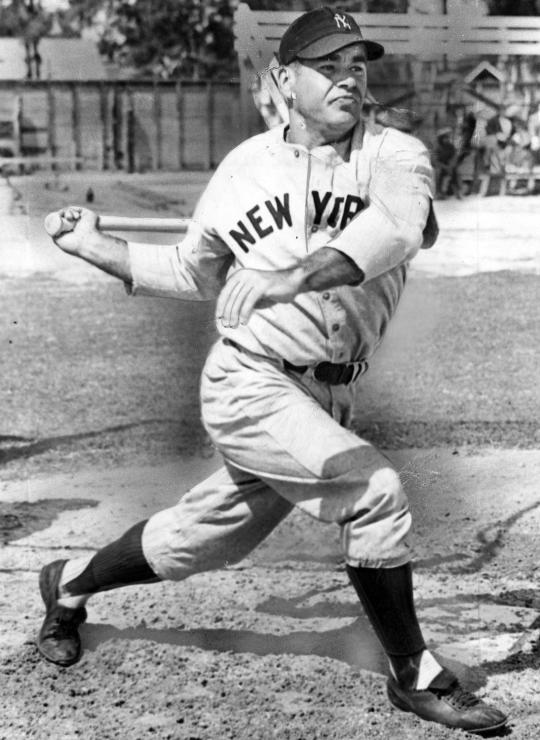

Keller, who hit .500 during his sophomore season at Maryland, also played for the Terrapins’ football and basketball teams. But baseball was his destiny – and the Yankees signed him to a contract worth a reported $2,500 following his 1936 season, agreeing to let him join the organization after he graduated.

Keller, however, decided to report to the Yankees Double-A team in Newark in the spring of 1937. He hit .353 with 120 runs scored in 145 games for the Bears that year. He returned to Maryland to finish his degree in agriculture after the season, and the Yankees sent him back to Newark for the 1938 campaign.

“I’ll never forget the day Charlie reported to Newark out of the University of Maryland in ’37,” Willie Klein, a reporter, told the Daily News. “Our manager, Oscar Vitt, took one look at him in batting practice, missing pitch after pitch, and said to me: ‘He’s got to be on the team.’

“I asked him: ‘How could you say that? He hasn’t hit anything yet.’ And Vitt said: ‘Yeah, but look at that swing.’”

In 1938, Keller hit .365 with 211 hits and 22 home runs for the Bears. By 1939, Keller was in the Yankees’ lineup.

“I should have been in the major leagues two years earlier than I was,” Keller told the Daily News following his playing career. “I led the International League in batting, runs, hits and triples (in 1937) and didn’t even get invited to Spring Training the next year.”

Known as King Kong – a nickname he did not like – for his brute strength, Keller hit .334 with 11 homers, 87 runs scored and 83 RBI in 1939. He was widely compared to Red Sox rookie Ted Williams, who hit .327 that season.

Keller was often judged as the better player.

“Keller is the more serious type,” Grantland Rice, the 1966 BBWAA Career Excellence Award winner, wrote that year. “Williams…may be intense enough at the plate, but he leans toward the lighter side of life. At the ages of 21 (Williams) and 23 (Keller) both have their chance to go a long, long way for many, many years.”

The Yankees won their fourth straight American League pennant that year and entered the World Series as the heavy favorites against the Reds. The 23-year-old Keller, batting third and playing right field in a lineup that included future Hall of Famers Joe DiMaggio, Bill Dickey and Joe Gordon, hit .438 with three homers, eight runs scored and six RBI in the four-game sweep – including a two-homer outburst in Game 3 that made him the talk of the sporting world.

“I just swung,” Keller told the Associated Press of both blasts – the second of which increased a one-run New York advantage to 6-3 in a game the Yankees would win 7-3.

Had the World Series MVP award existed in 1939, Keller likely would have won it.

In 1940, Keller bounced between left field and right field as manager Joe McCarthy looked for the hot hand between Tommy Henrich (who played right field) and George Selkirk (who played left). By the end of the season, Keller had 21 homers, 93 RBI, 102 runs scored and a league-high 106 walks while earning his first All-Star Game selection.

It marked the only season of the 1940s where Williams played and did not lead the AL in walks. The Yankees, however, failed to win the World Series for the first time since 1935, finishing two games behind the Tigers in a hotly contested pennant race. And many claimed Keller – whose WAR of 5.6 ranked sixth overall in the AL – was a victim of the sophomore jinx.

In 1941, Keller started slowly but warmed up just as DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak was coming to an end. Keller hit .330 with 10 homers and 27 RBI in July, finishing with 33 homers, 102 runs scored, 122 RBI and 102 walks. He finished a career-best fifth in the AL MVP voting and hit .389 with five runs scored and five RBI in the Yankees’ five-game win over the Dodgers in the World Series, tying for the team lead in runs scored and RBI with Gordon.

In Game 4, it was Keller who capitalized on the famous dropped third strike by Dodgers catcher Mickey Owen that allowed Henrich to reach base with two outs in the ninth and Brooklyn leading 4-3. DiMaggio followed with a single off Hugh Casey, and Keller then doubled to right field – scoring Henrich and DiMaggio to give the Yankees a lead that would turn what would have been a two-games-apiece Series tie into a three-games-to-one Yankees lead.

Keller posted similar numbers in 1942 with a .292 average, 26 homers 106 runs scored, 108 RBI and 114 walks, then followed that with a .271 average, 31 homers, 86 runs scored, 91 RBI and a big league-best 106 walks in 1943. Keller’s WAR of 19.9 from 1941-43 was the best of any player in baseball – save Williams (who played in only two of those years).

In January of 1944, Keller enlisted in the United States Merchant Marine – the first active player to do so – and coached the maritime service boxing team from Pensacola, Fla., that participated in Golden Gloves tournament in Jacksonville. He missed all of the 1944 season in the service while serving mostly in the Pacific, then returned to the Yankees lineup on Aug. 19, 1945 after his discharge. He hit .301 with 10 homers and 34 RBI in 44 games, showing he had retained his baseball skills.

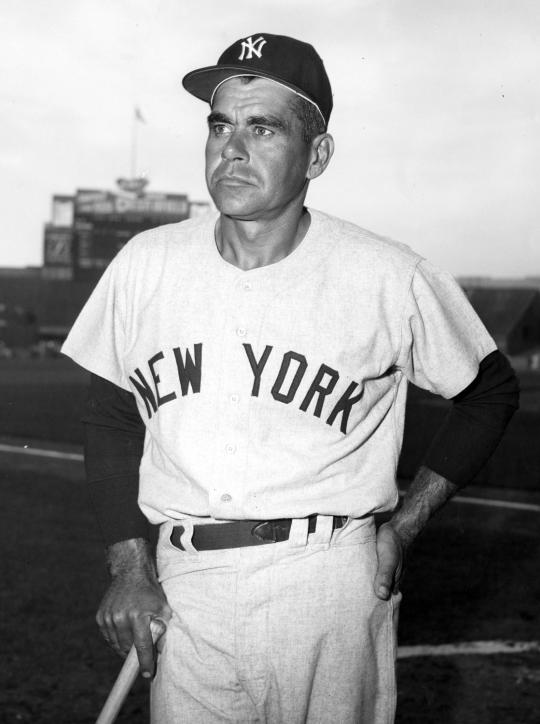

Keller was an All-Star again in 1946, hitting .275 with 30 homers, 101 RBI and 113 walks. But his back began aching as the season progressed. He made the All-Star team again in 1947 but appeared in only 45 games – none after June 23 – and eventually underwent surgery to remove a ruptured disc.

For the next five seasons, Keller gamely tried to play through pain but found it almost impossible. He hit .267 with six homers and 44 RBI in 1948 as the Yankees began transitioning away from their championship outfield of DiMaggio, Henrich and Keller. By 1949 – with Gene Woodling and Hank Bauer getting regular assignments from new manager Casey Stengel – Keller played in just 60 games, hitting .250 with three homers and 16 RBI.

But Keller’s presence helped the Yankees win World Series titles in 1947 and 1949, giving Keller five rings in 11 seasons in New York.

“I hit a pop-up in a game in ’48. I didn’t run it out,” Yogi Berra told The Record of Hackensack, N.J. “Charlie wasn’t playing in the game but he came to me in the dugout between innings. He didn’t usually say much, so I was surprised. He asked me if I was feeling all right. I said: ‘Yeah, sure.’

“And then, in a voice that knifed to the real matter at hand, Keller said: ‘Then why didn’t you run it out?’”

Finally – with Mickey Mantle and other outfield prospects on the horizon – the Yankees released Keller on Dec. 6, 1949. He quickly signed on with the Tigers.

“(I am) glad to get the chance to play,” Keller, who turned down an offer to manage in the Yankees’ minor league system, told the Associated Press. “I still have quite a bit of good baseball left. (But it will) feel funny to play against the Yankees.”

Keller’s chronic back problems, however, limited him to just 50 games in 1950 and 54 in 1951 – totaling 32 hits and five home runs over those two seasons.

After being released by Detroit following the 1951 campaign, Keller returned to the Yankees in a mostly ceremonial role late in 1952, appearing in two games in September.

“Keller will be worth his weight in gold on the Yankee bench,” said Yankees broadcaster Mel Allen, “even if he doesn’t play.”

The Yankees voted to award Keller a $1,000 World Series share after the Bronx Bombers once again defeated Brooklyn in the Fall Classic. Soon after the end of the World Series, Keller was released – ending his career.

He finished with a .286 batting average over 13 seasons – only six of which could be considered full. He totaled 189 home runs, 760 RBI and five All-Star Game selections – and played on six teams that won the World Series.

Keller’s son, Charlie Keller Jr., played four seasons in the Yankees minor league system from 1959-62, tearing up the lower minors his first three years before a back injury prematurely ended his career.

Following his retirement, Keller bred trotting horses as his Maryland farm, Yankeeland, earning a reputation as one of the best in the business. All his horses included some form of the word “Yankee”.

“Everybody knew Charlie Keller was a great ballplayer,” Henrich told the New York Daily News following Keller’s passing on May 23, 1990. “But he was a lot more than that. He was a no-nonsense kind of guy.

“Charlie Keller personified what the Yankees used to stand for.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1950 Bowman Johnny Lindell

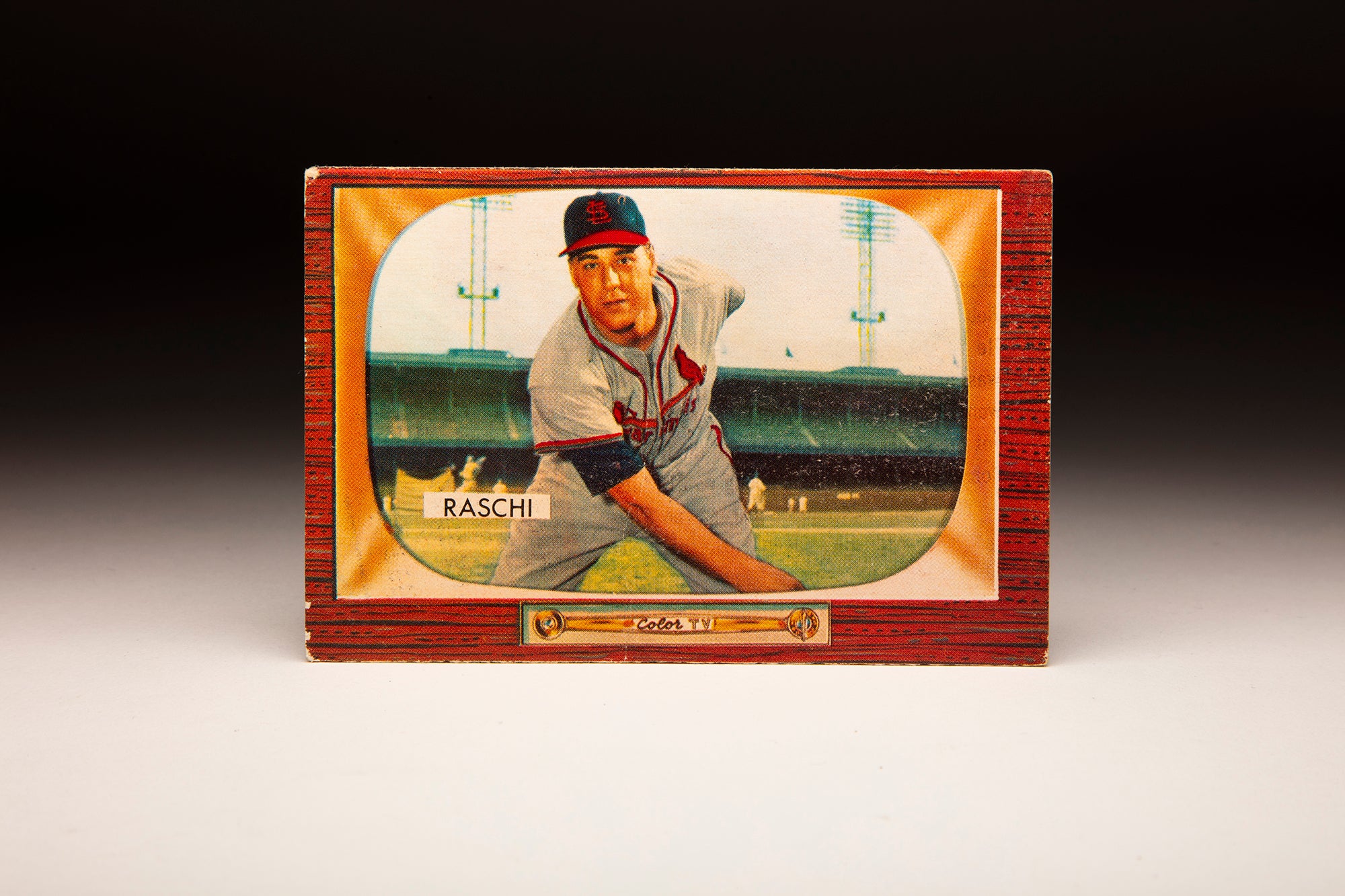

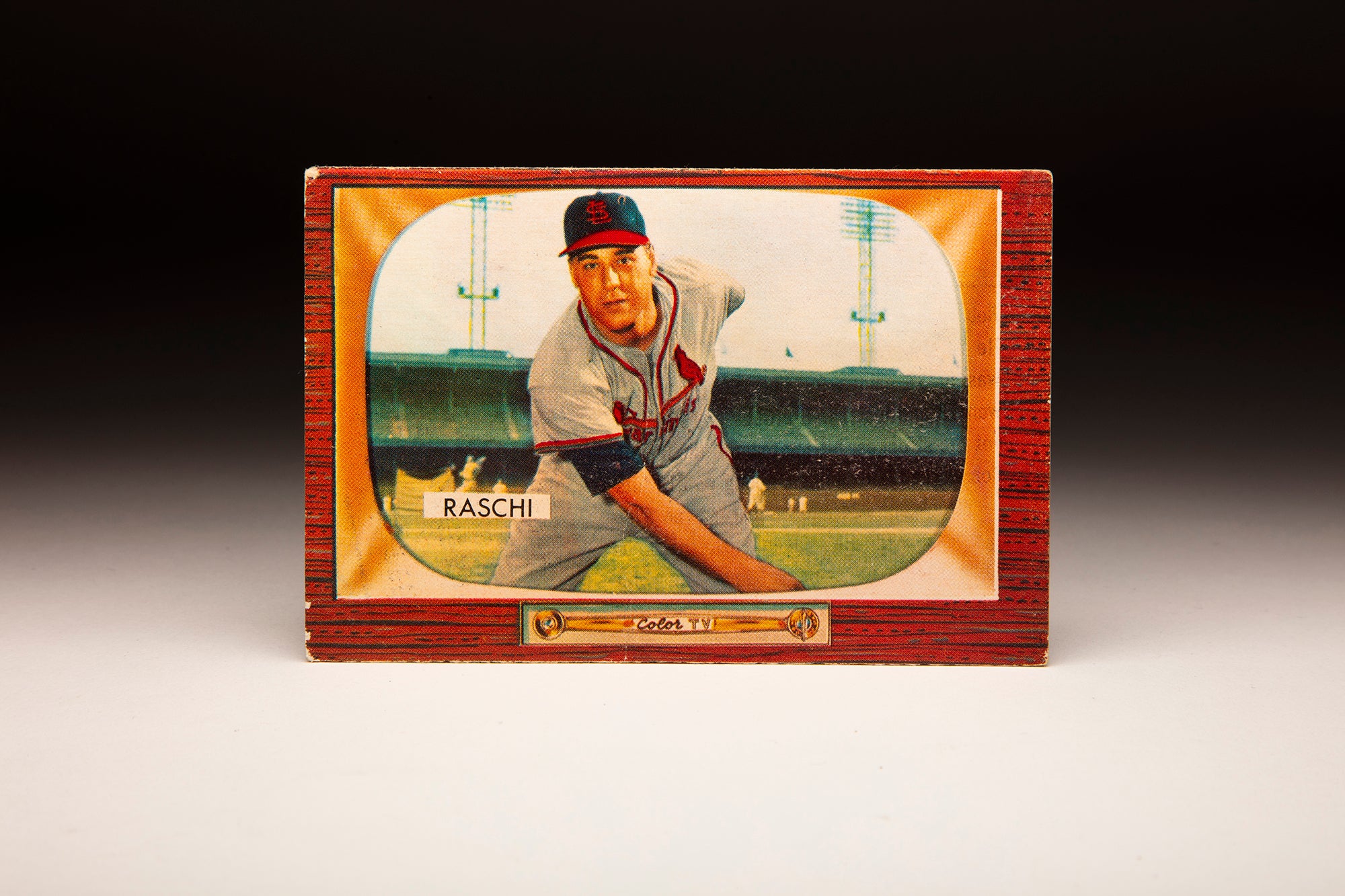

#CardCorner: 1955 Bowman Vic Raschi

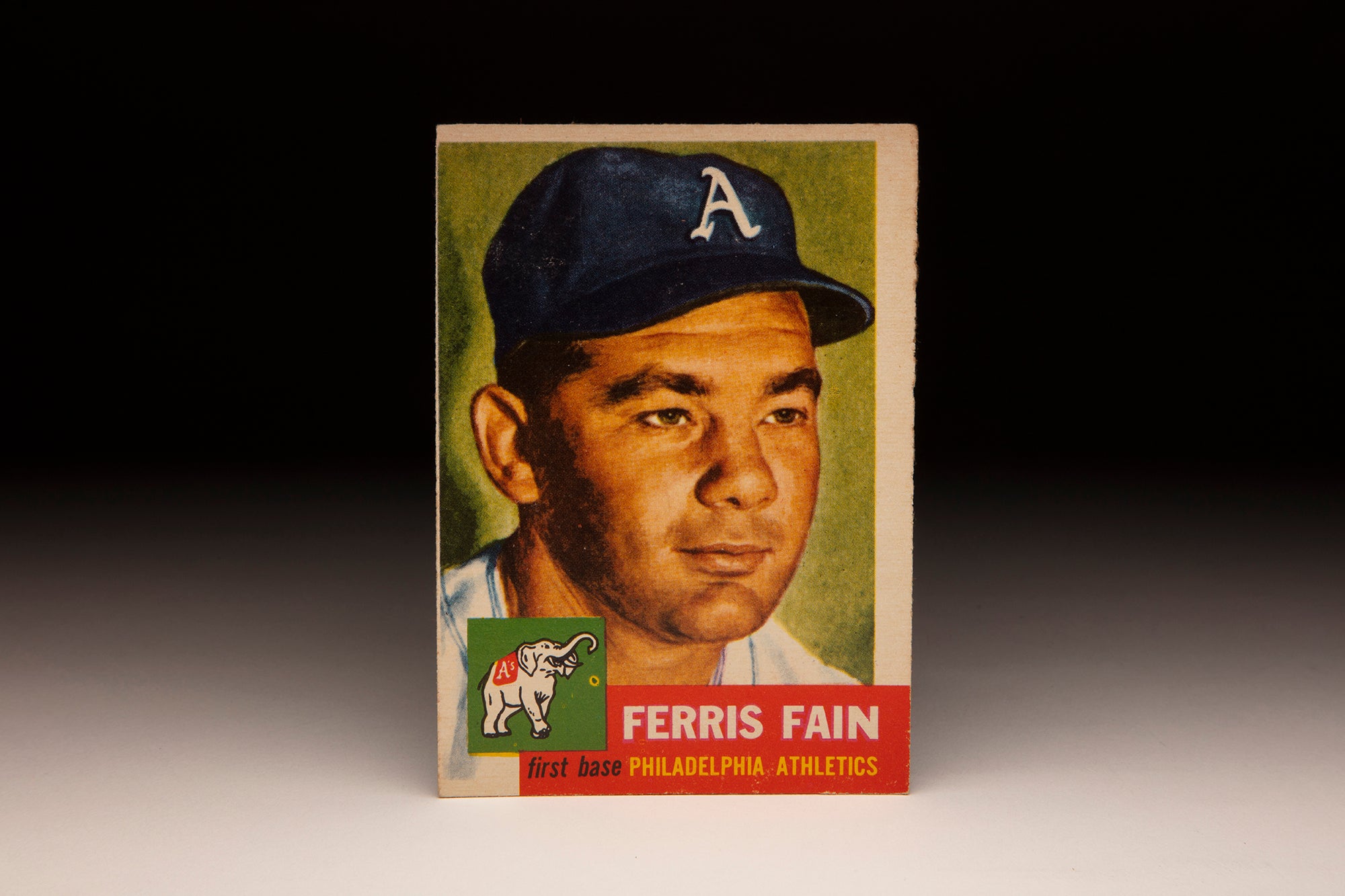

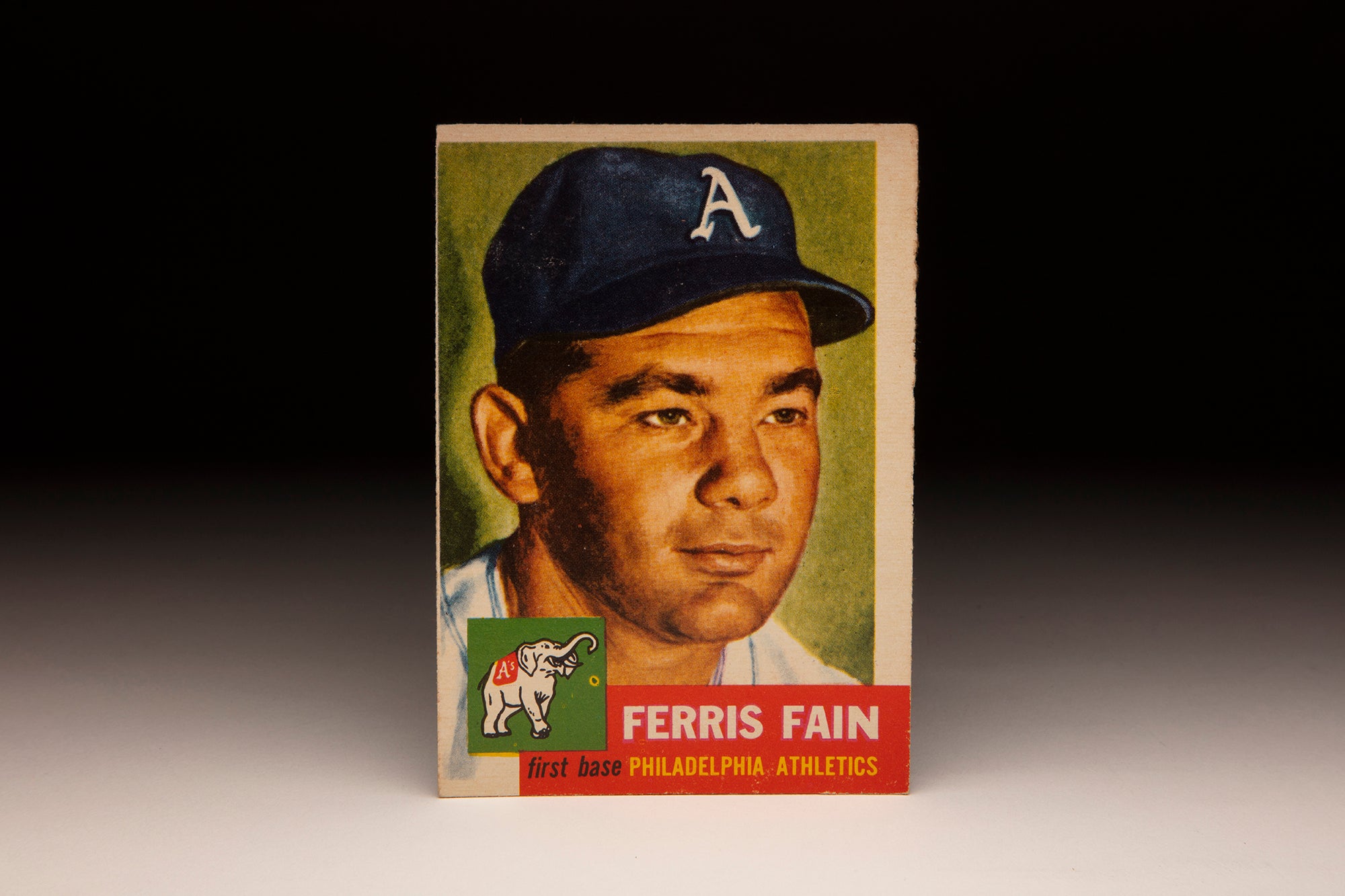

#CardCorner: 1953 Topps Ferris Fain

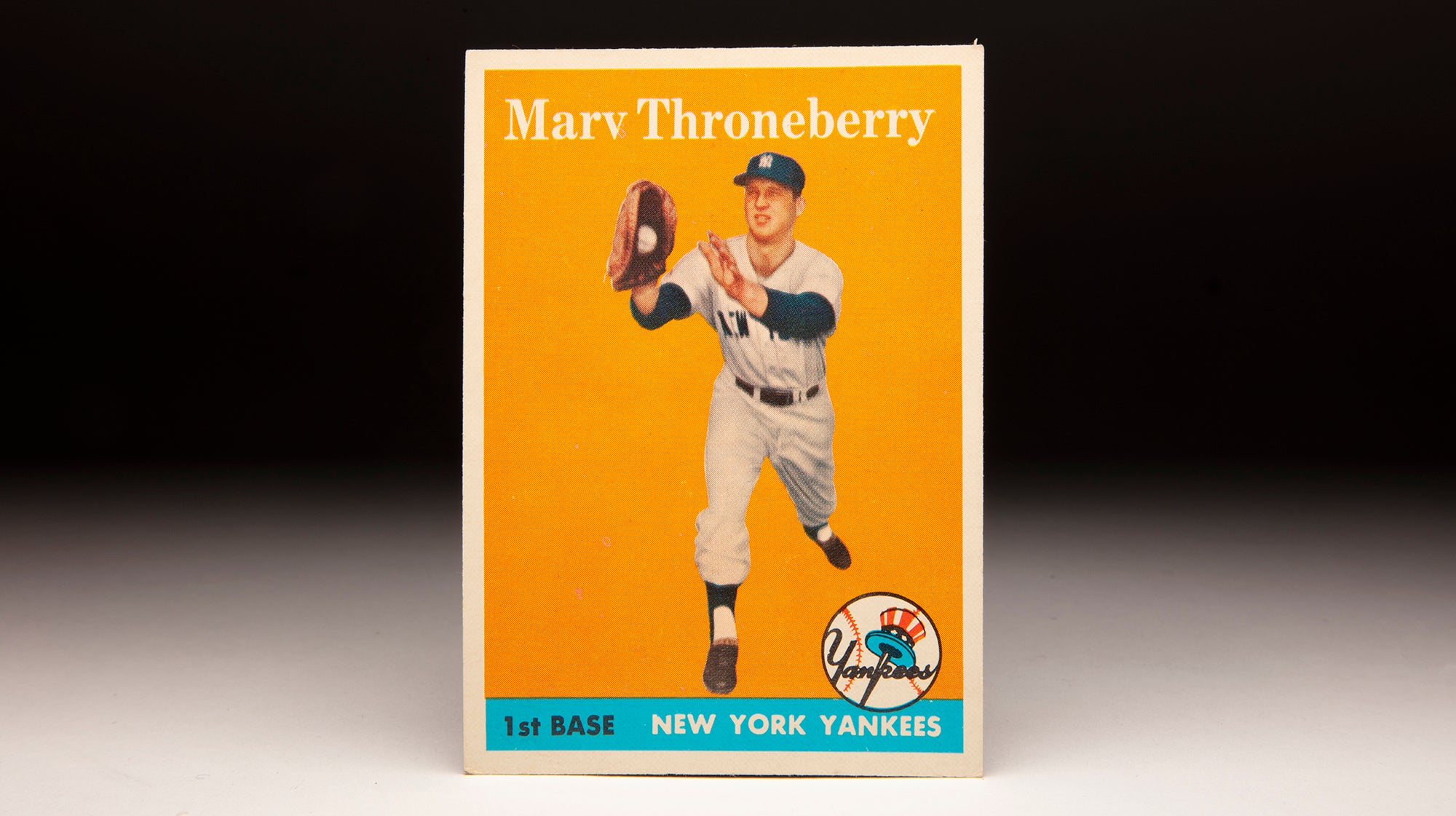

#CardCorner: 1958 Topps Marv Throneberry

#CardCorner: 1950 Bowman Johnny Lindell

#CardCorner: 1955 Bowman Vic Raschi

#CardCorner: 1953 Topps Ferris Fain