- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1960 Topps Charlie Neal

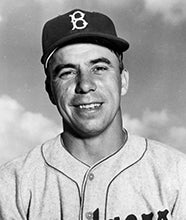

#CardCorner: 1960 Topps Charlie Neal

In an era where middle infielders were supposed to field first and provide an occasional hit at the plate, Charlie Neal combined power, speed and defense to become one of the most talked about players in the game.

Then in a flash, it was mostly gone. But for a few sparkling years in the late 1950s, Neal and the Los Angeles Dodgers redefined what was possible.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Neal was born Jan. 30, 1931, in Longview, Texas. Coming of age in a family whose father organized a local sandlot team, Neal spent plenty of time on the diamond despite the fact that his high school did not offer baseball as a sport. He overcame a fear of the ball as a youngster when his father moved him to shortstop and hit him endless ground balls in practice.

Neal played on semi-pro and Negro Leagues teams after graduation before signing with the Dodgers in the winter of 1950. In his first season in organized ball, Neal hit .301 with the Class D Hornell Dodgers in 1950, then methodically moved through the stocked Dodgers’ farm system. By 1954, the 23-year-old Neal hit .272 with 18 home runs, 20 steals and 101 runs scored for Triple-A St. Paul but was stuck behind Don Zimmer at shortstop on Brooklyn’s organizational depth chart.

Assigned to Triple-A Montreal in 1955, Neal appeared to be ready for the majors.

“He’s a better fielder right now that Jackie Robinson was when he broke in with the (Montreal) Royals,” Royals manager Greg Mulleavy told the Montreal Gazette. “That was in 1946 and Jackie (was 27) at the time. (Neal) is only 23.”

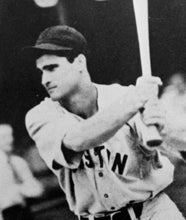

Neal played mostly second base in 1955 as the Dodgers had another prospect, Chico Fernández, at shortstop. Neal virtually duplicated his 1954 season, hitting .274 with 111 runs scored, 16 homers and 13 stolen bases. The Red Sox thought so much of Neal that they reportedly offered $125,000 for him with the intent of making him the first Black player in franchise history.

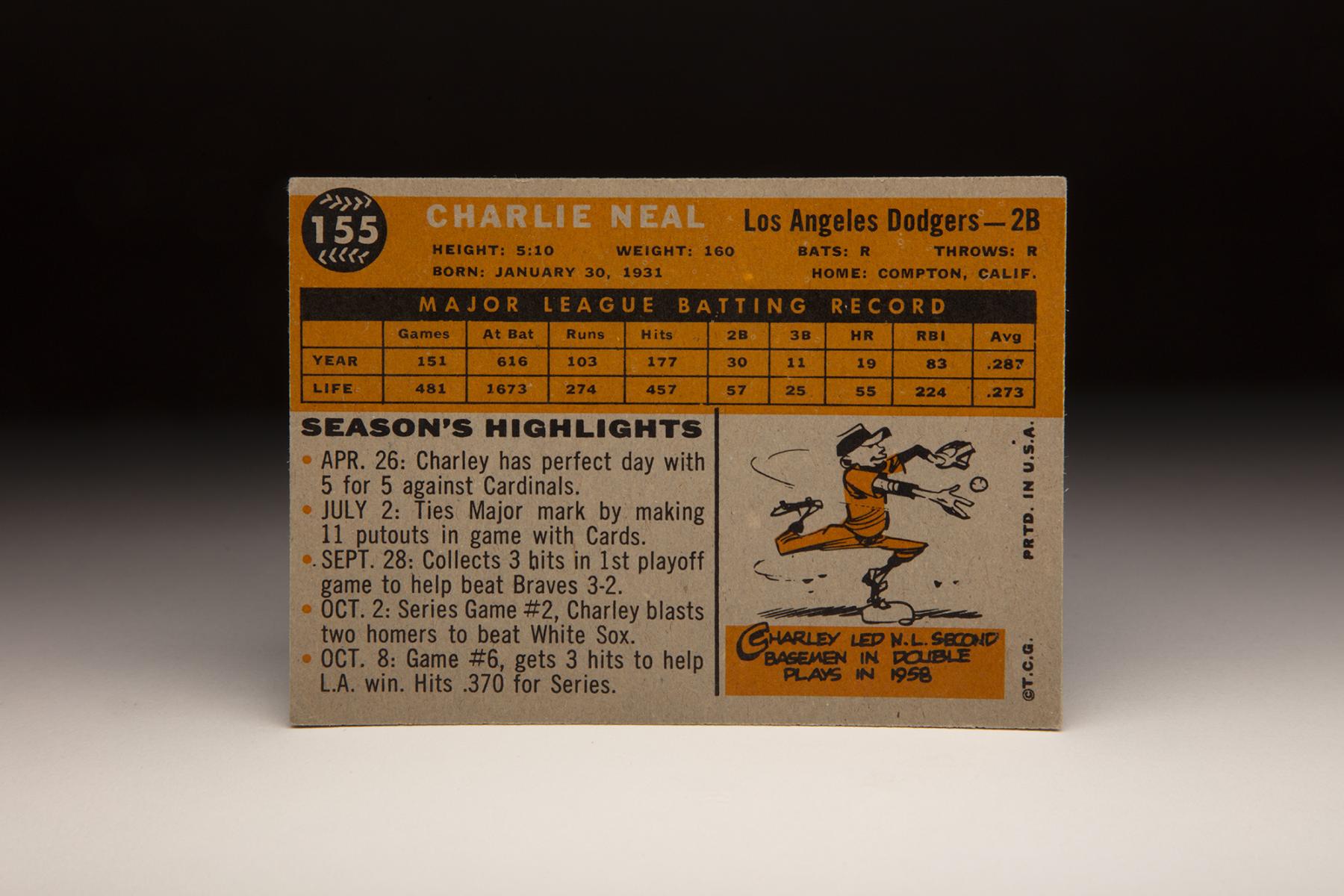

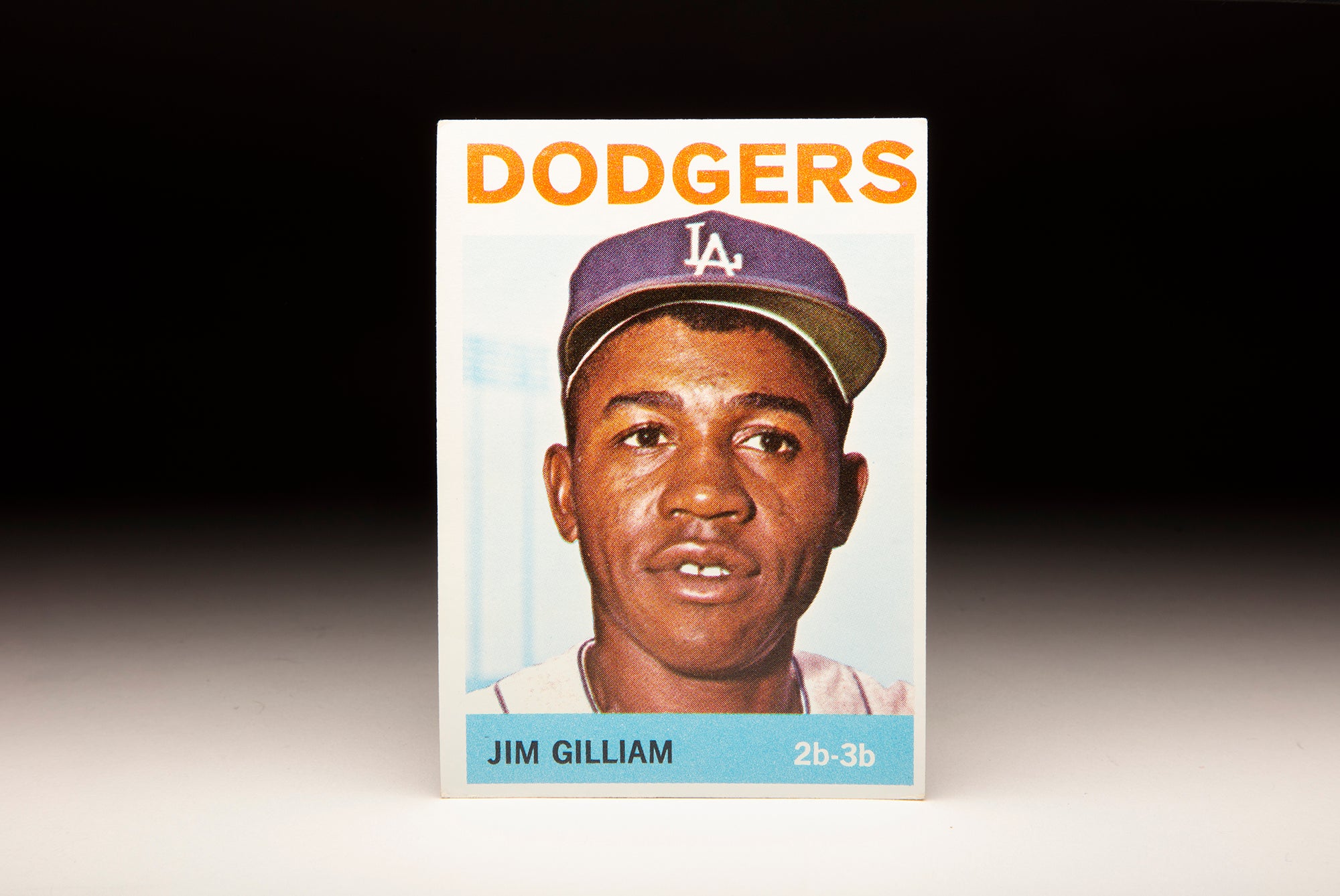

Fresh off their 1955 World Series victory, however, the Dodgers made Neal their Opening Day second baseman in 1956 – moving Junior Gilliam to left field.

“This is what I’ve been waiting and working for through six long years,” Neal told the United Press. “I’m 25 and it’s about time I got where I’m going.”

Neal started Brooklyn’s first 15 games, hitting a respectable .269 but with only two extra base hits. With the Dodgers at 8-7, manager Walter Alston moved Gilliam back to second base and benched Neal – easing him into a reserve role for the rest of the season.

In 62 games that year, Neal hit .287 and slugged .382, helping the Dodgers win their fourth National League pennant in five seasons. Neal played in one game in the World Series, going 0-for-4 with an error at second base in Game 3 in a 5-3 Yankees’ victory. The Dodgers would lose the Fall Classic in seven games, but Neal’s World Series time to shine would come.

Neal again made the Dodgers’ Opening Day roster in 1957 but had no steady job as Gilliam remained at second base, Zimmer at shortstop and newly acquired Randy Jackson at third. But an injury to Jackson in April put Neal back in the mix, and by June Alston had installed Neal as his regular shortstop. In 128 games, Neal hit .270 with 12 home runs and 62 RBI.

The Dodgers moved to Los Angeles following the 1957 season, and Neal added power to his resume in 1958 – hitting 22 home runs while taking advantage of the tall-but-close left field wall at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. An aging Dodgers team finished 71-83 – and though Neal re-established himself at second base that year, the immediate future for the franchise did not seem bright.

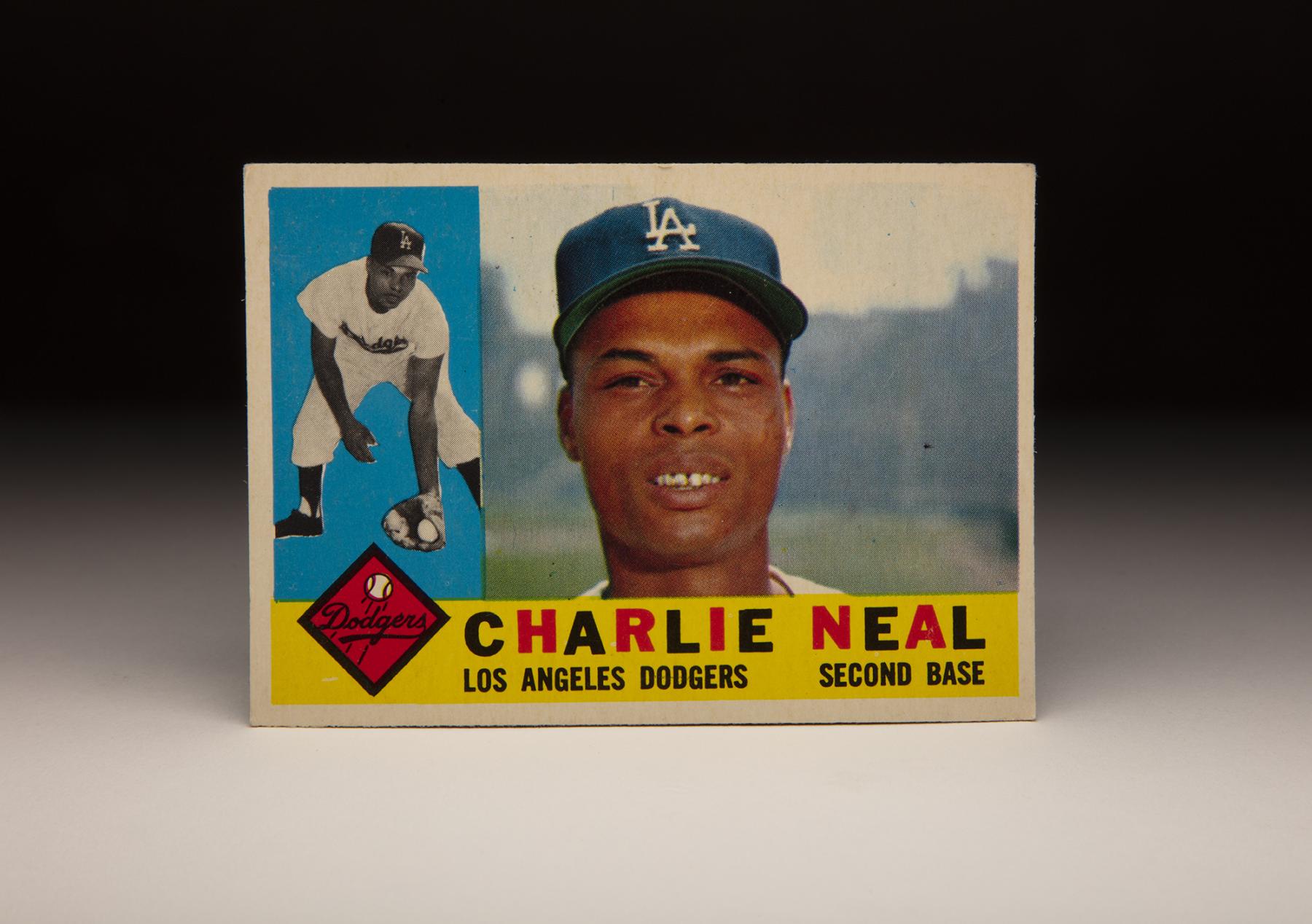

But Alston pushed all the right buttons in 1959 – and Neal was at the heart of the Dodgers’ attack. In 151 games, Neal hit .287 with 103 runs scored, 30 doubles, a league-leading 11 triples, 19 home runs and 83 RBI. Neal even led the majors in sacrifice bunts with 21 and won a Gold Glove Award at second base after leading NL second basemen with a fielding percentage of .989.

His 286 total bases trailed only future Hall of Famers Bobby Doerr (304 in 1950), Red Schoendienst (292 in 1957) and Robinson (289 in 1951) among second basemen in the 1950s.

On the final day of the regular season against the Cubs – with the Dodgers needing a win to remain tied with the first-place Braves – Neal tripled and scored in the third inning and belted a two-run homer in the fifth to help Los Angeles win 7-1.

Neal was 3-for-5 with a run scored in Game 1 of the best-of-3 playoff against the Braves, helping the Dodgers win 3-2. Then in Game 2, Neal’s fourth-inning home run off Lew Burdette cut the Milwaukee lead to 3-2 – and the Dodgers went onto win 6-5 in 12 innings to advance to the World Series.

In the Fall Classic against the White Sox, Neal’s Game 2 performance likely saved the series for the Dodgers. Down one game to none after losing the opener 11-0 and trailing Game 2 2-0 in the fifth inning, Neal homered off Bob Shaw to cut the deficit in half.

Chuck Essegian’s pinch-hit home run tied the game in the seventh, and – after a Gilliam walk – Neal took Shaw deep again on a 2-and-1 fastball to give the Dodgers a 4-2 lead that Larry Sherry would protect for an eventual 4-3 win.

A beaming Neal was congratulated by Gilliam as he crossed home plate at Comiskey Park.

“I wasn’t thinking when I hit the second one that it might win the game,” Neal told the Associated Press. “But I was sure glad to see it go. That was one of the biggest thrills of my career.”

Neal added two more hits in Game 3, including an RBI double in the bottom of the eighth that gave Los Angeles an insurance run in a game the Dodgers won 3-1.

Neal was hitless in Game 4 and 1-for-5 in Game 5. Then in Game 6 – with the Dodgers one win away from the title – Neal was 3-for-5 with a run scored and two RBI. His two-run double in the fourth inning was part of a six-run rally that gave the Dodgers an 8-0 lead that turned into a 9-3 win.

Neal finished the World Series with a .370 batting average (10-for-27) with two homers, two doubles, four runs scored and six RBI. Only a legendary performance by Sherry – who won two games and saved two others for the Dodgers – denied Neal Most Valuable Player honors.

Neal, who was named to his first All-Star Game in 1959, was selected to both Mid-Summer Classics in 1960 despite slumping to a .256 batting average and 40 RBI in 139 games. Turning 30 years old in 1961, Neal appeared in just 108 games that season battled a knee injury and an infection, hitting .235.

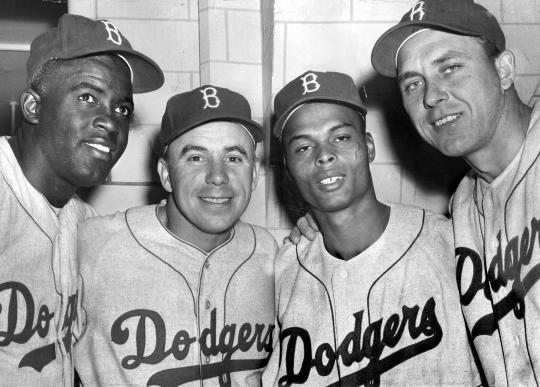

And following that season, the Dodgers traded Neal to the expansion New York Mets along with Willard Hunter, receiving Lee Walls and $100,000.

“There’s no doubt in my mind Charlie will help the Mets,” Dodgers general manager Buzzie Bavasi told the Associated Press. “He may bounce back and have a great year.”

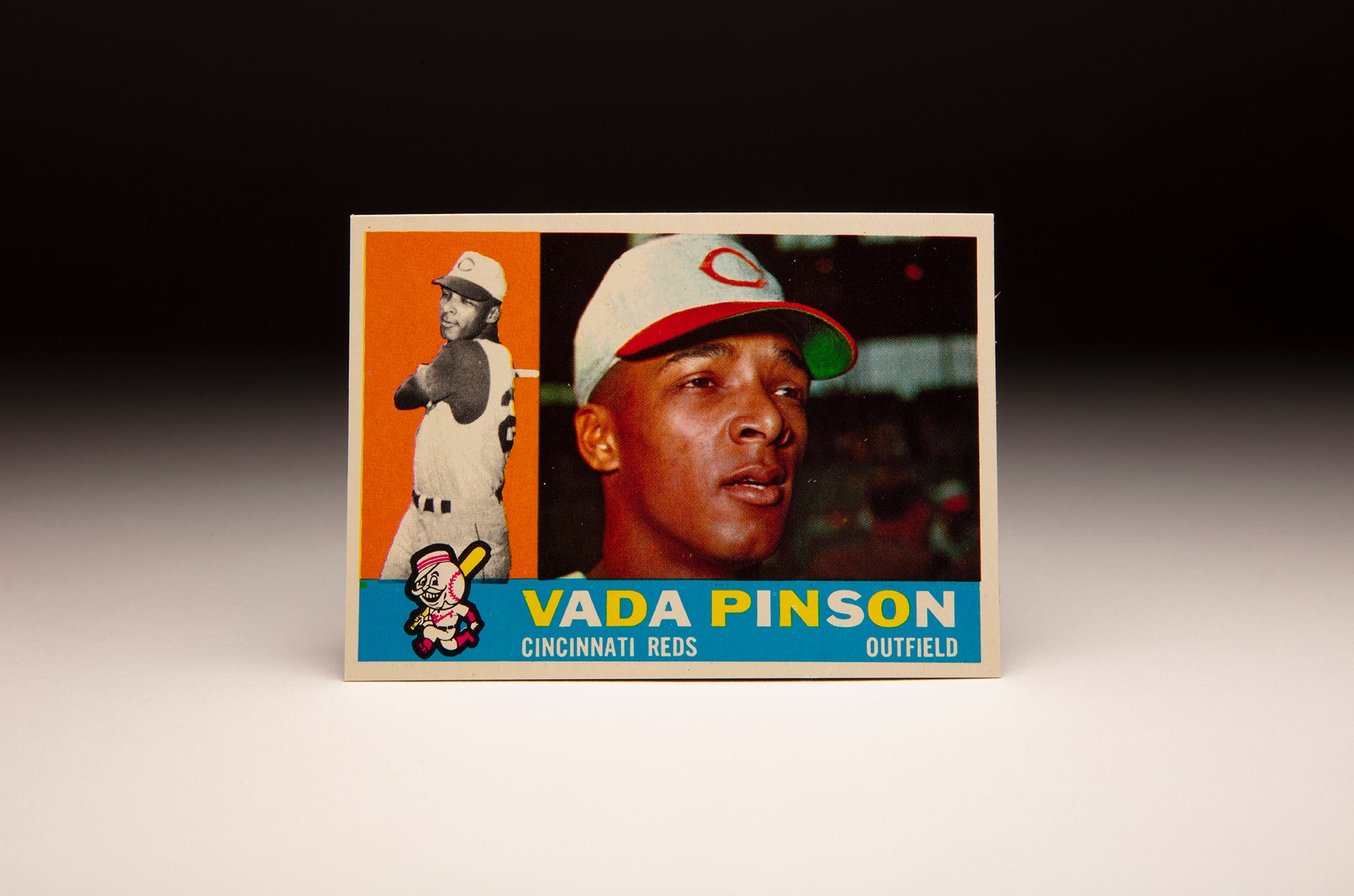

Neal did bounce back in 1962, hitting .260 with nine triples, 11 home runs and 58 RBI while playing second base and shortstop for a Mets team that lost 120 games. Neal moved to third base in 1963, hitting .225 through 72 games when the Reds traded for him on July 1.

After hitting .156 in 34 games with the Reds in 1963, Neal was released at the end of Spring Training in 1964, closing out his big league career.

Neal returned home to Texas and passed away from heart failure on Nov. 18, 1996. In eight seasons in the big leagues, he hit .259 with 461 runs scored and 391 RBI, earning three All-Star Game selections and his 1959 World Series ring.

It was a career that seemed to end right after it peaked. But Charlie Neal left a legacy that included a shining moment at the top.

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum