- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1964 Topps Dick Radatz

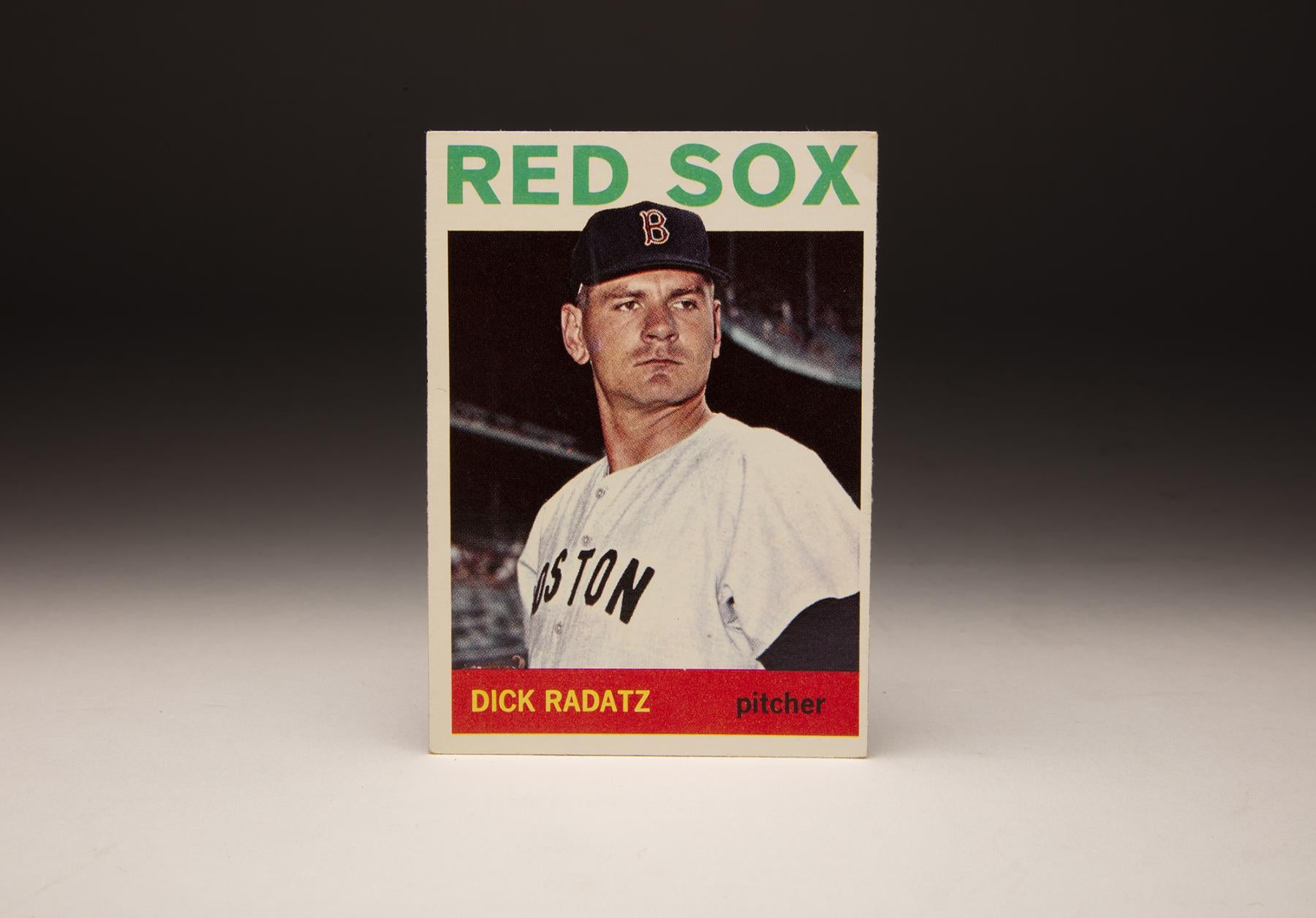

#CardCorner: 1964 Topps Dick Radatz

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

If it’s possible to intimidate through a baseball card, Dick Radatz was one of the few players who could fulfill such a task.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

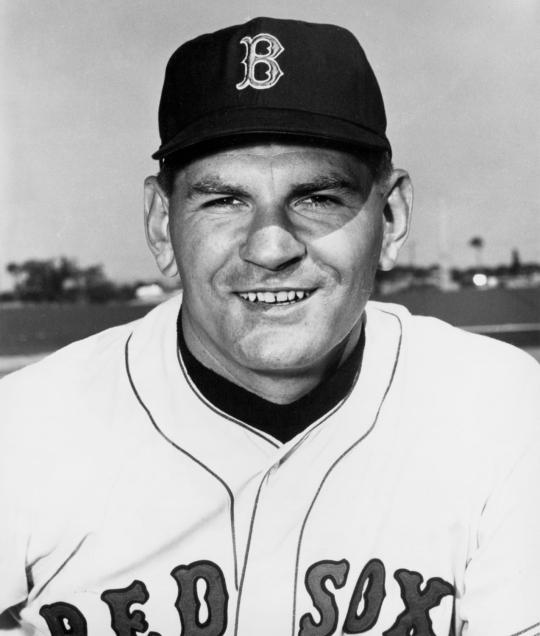

His 1964 Topps card shows him just the way that many Boston Red Sox fans of the era remember him: with a sharp, steel-like jaw, a tense and terse expression on his face and dark, staring eyes that could melt an opposing hitter – or a cameraman in this case.

If you were photographing Radatz for Topps back in the 1960s, you probably would have felt motivated to get the picture taken in one shot. After all, there was no need to spend any more time than necessary in photographing the pitcher known as “The Monster.”

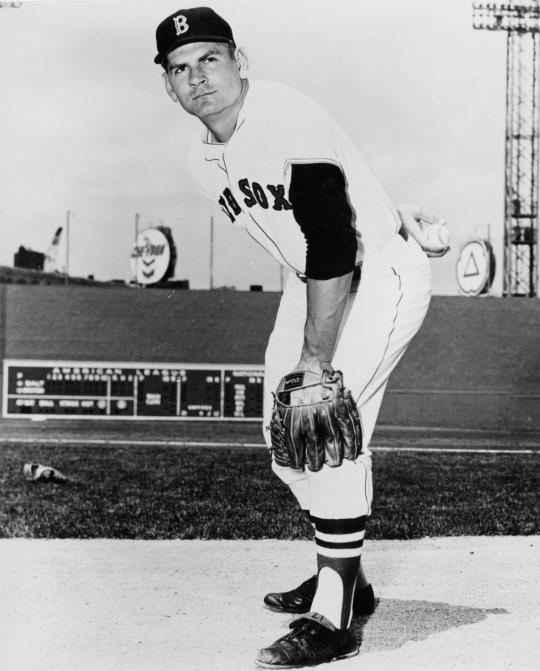

None of this should be interpreted as an indication of Radatz’ personality or character. He was neither mean, nor unfriendly. No, it all had to do with his appearance, and his persona on the mound. At 6-foot-6 and 230 pounds – those are his listed dimensions, but some of his contemporaries felt that he weighed even more than that – Radatz was one of the largest players of his era. It was an era that predated weight training, performance-enhancing substances and the general emphasis that pitchers needed to be at least six feet tall.

In today’s game, Radatz might have blended into the crowd, but in the game of the 1960s, he looked more like one of the inhabitants of the late 1960s TV show, Land of the Giants.

Radatz sometimes used his size as part of his sense of humor. While attending Michigan State University in the 1950s, Radatz played basketball and baseball as a freshman. The school’s football coach, Clarence “Biggie” Munn, took one look at Radatz and inquired as to his availability for the varsity football team.

“How come you didn’t come out for football?” the coach asked him. Radatz replied in his typical kidding fashion, “No thanks, Mr. Munn. I don’t like raw meat.”

As a starting pitcher at Michigan State, Radatz so dominated the opposition that he drew the interest of scouts from several major league teams. There might have been more suitors, but Radatz had a reputation for losing his temper, which turned some scouts away. Yet, his coach also praised him for being highly coachable. A contract with the home team Detroit Tigers might have made sense, especially since Radatz had long regarded Tigers great Hal Newhouser as a hero, but instead Radatz signed with another American League club: the Boston Red Sox.

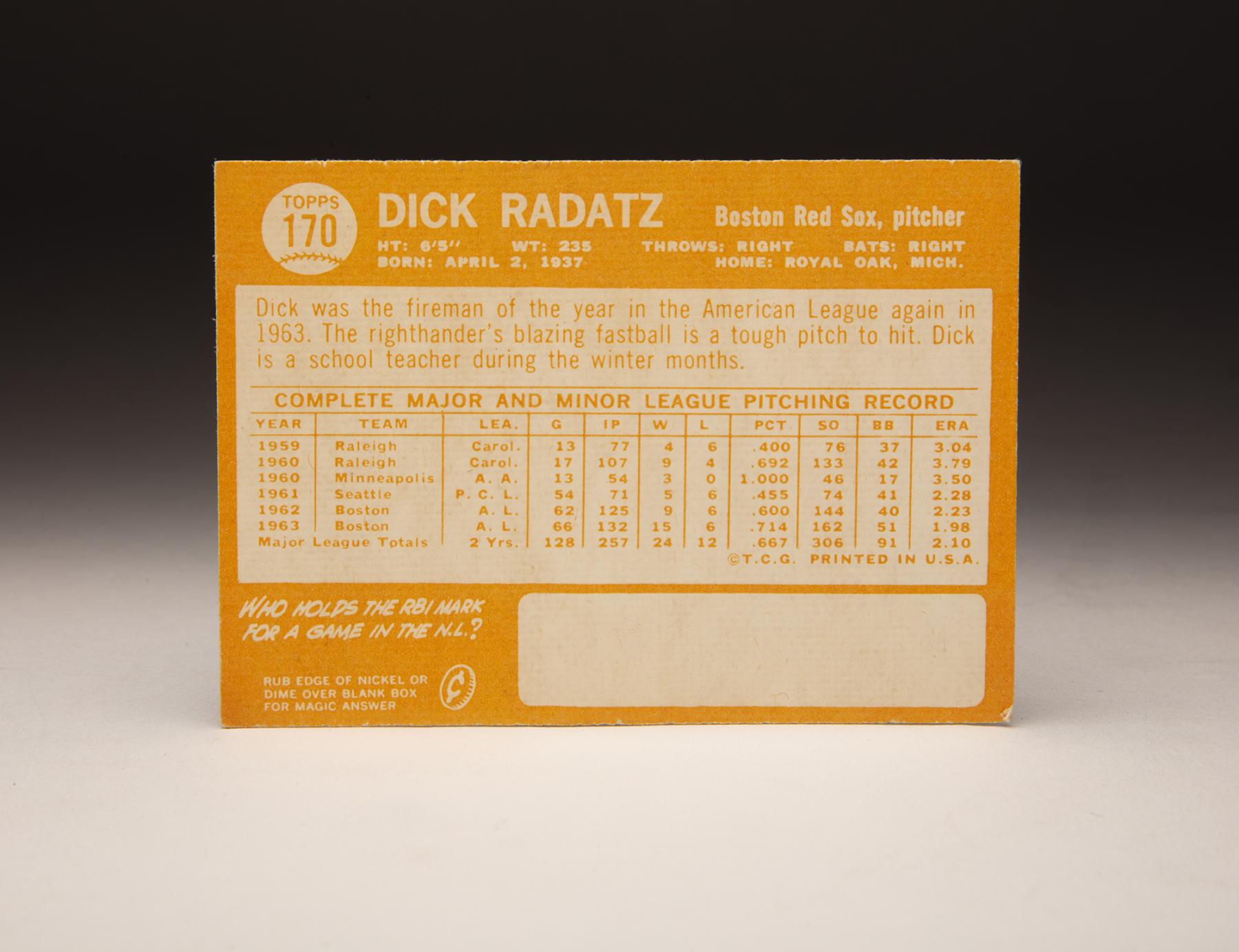

The Red Sox assigned Radatz to Raleigh of the Class B Carolina League, where they used him as a starter. Radatz posted an ERA of 3.04 and showed off a power fastball with movement. He continued to pitch well at Raleigh in 1960, before earning a midseason promotion to Triple-A Minneapolis of the American Association. The hulking right-hander showed himself more than capable of the advanced minor league assignment, striking out 46 batters in 54 innings and winning all three of his decisions.

In 1961, the Red Sox assigned Radatz to their relocated Triple-A venue, the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League, while also converting him to a reliever. At first, Radatz balked at the role, but then his manager, Johnny Pesky, explained that the Red Sox needed a relief pitcher in the worst way, which might expedite his arrival in the major leagues. Once Radatz became aware of that, he embraced his role. Though the PCL was known as a hitters’ league, Radatz dominated, posting an ERA of 2.28 in 54 games.

Reporting to Spring Training with the Red Sox in 1962, Radatz made the Opening Day roster. When informed that his major league salary would amount to only $7,500, the league minimum, Radatz expressed no problem with that. He recalled his reaction in an interview with Al Hirshberg of Sport magazine. “I don’t care if you give me five bucks (for the season),” Radatz said, “as long as you take me back to Boston.”

Radatz took to the major leagues with relative ease. Over his first 12 relief appearances, he did not allow a single run. With an overpowering fastball and a slow sidewinding motion that was deceptive, Radatz had his way with American League hitters. By season’s end, he had appeared in a league-leading 62 games, saved 24 games (which also led the league), and struck out 144 batters in 124 innings. The Sporting News named him Fireman of the Year, while league beat writers voted him third place in the Rookie of the Year balloting. He also finished 21st in the league MVP vote.

Somehow, Radatz pitched even more effectively in his second season. He lowered his ERA from 2.24 to 1.97. He increased his strikeouts to 162 and piled up 132 innings. He also won 15 games. And keep in mind, Radatz did all of this out of the bullpen; he would not make a single start over the course of his seven years in the major leagues.

Radatz’ pitching was effective enough, but it was also his stature that drew attention. At his high point, he may have weighed as much as 280 pounds. Some opponents called him “Frankenstein.” A few others referred to him as the “White Whale” or “Moose.” Ultimately, the nickname that caught on was “The Monster.” At first, Radatz bristled at the name, expressing concern that his family did not appreciate, but eventually but came to accept it.

“I realize no harm is intended,” Radatz told the Sporting News.

Radatz’ size complemented his fastball. How hard did Radatz throw? It’s difficult to say with certainty, since his fastball was never precisely measured by a radar gun, but a conservative estimate placed him in the range of 95 to 97 miles an hour. Some eyewitnesses believed that he approached the 100-mph plateau.

The Red Sox so loved Radatz’ relief pitching that they asked him to pitch even more in 1964. Logging 157 innings in 1964, Radatz led the league in saves and games finished. For the season, he struck out 181 batters, a total that exceeded that of many starting pitchers throughout the league.

And for the third straight season, he received some support from the voters in the American League MVP balloting.

Radatz was not only the league’s most dominant relief pitcher, he was also one of its most flamboyant. Upon recording the final out of a game, Radatz would thrust both of his fists above his head and stomp off the mound. This was the kind of on-field demonstration that was foreign to a conservative sport at the time, but in time, it would seem tame in comparison with later on-mound showmen like Al “The Mad Hungarian” Hrabosky and Brad “The Animal” Lesley.

All in all, Radatz made a lasting impression during his first three seasons. In retrospect, it’s also tempting to say that he was overused during those early years and that such a remarkable workload would lead to arm trouble. For his part, Radatz believed that his late-career problems were not caused by injury, but by failed pitching mechanics.

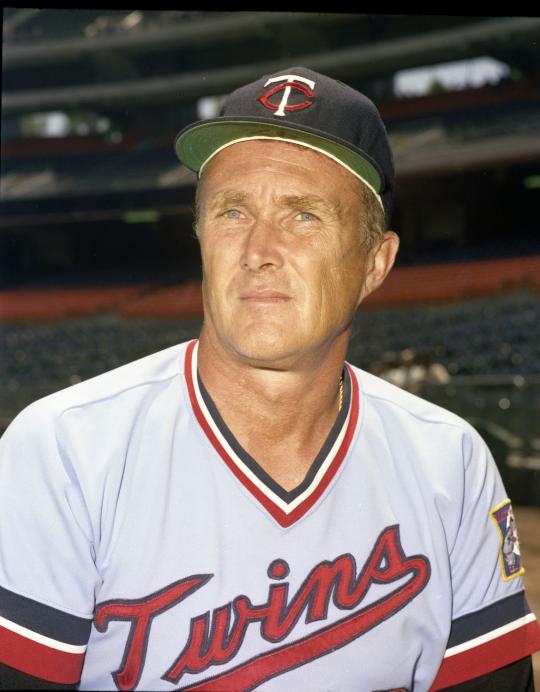

In 1965, Radatz experienced a dip in performance, just as the Red Sox tried to curb his workload. Prior to the season, new manager Billy Herman announced that he would only bring Radatz into games in which the Red Sox led. Unfortunately, the strategy didn’t produce the intended results. For the season, Radatz’ ERA rose to 3.91, well above the 2.29 mark he posted in 1964.

In 1966, Radatz’ game began to fall apart. He pitched so poorly over his first 16 outings that the Red Sox abruptly traded him in early June. They sent him to the Cleveland Indians for two pitchers, veterans Don McMahon and Lee Stange.

On the surface, the trade allowed Radatz to join an Indians team that was in first place at the time. But the Indians would fade – and Radatz would pitch at about the same level in Cleveland as he had recently in Boston.

Radatz returned to the Indians in 1967, but made only three appearances before being dispatched again. The Indians traded him to the Chicago Cubs for a player to be named later, who turned out to be an obscure minor league outfielder.

Radatz made 20 appearances for the Cubs, but lost control of his fastball, issuing 24 walks in 23 innings. Frustrated by his wildness, the Cubs demoted him to Triple-A Tacoma. Upset by the demotion, Radatz threatened to retire, but then reconsidered and reported to the Cubs’ affiliate. There he pitched brutally, allowing 22 earned runs in 22 innings.

With his performance so uncharacteristic, the Cubs asked Radatz to undergo a medical examination. Doctors determined that he had a pinched nerve in his shoulder, which was causing numbness in his right hand.

Through proper rest, the pinched nerve healed, allowing Radatz to rejoin the Cubs the following spring. The Cubs pitched him in a preseason B-game and watched in anguish as he threw 24 consecutive balls during one stretch. A week and a half later, the Cubs released Radatz. In late April, he signed on with the Detroit Tigers, who used him at Triple-A Toledo for the entire summer.

In 1969, the Tigers brought Radatz back to the major leagues. He pitched effectively in 11 games, posting a 3.88 ERA.

And then for some reason, they sold his contract to the expansion Montreal Expos.

The move mystified Radatz and others, but it may have been a sign of the power struggle between Tigers pitching coach Johnny Sain and the team’s manager and front office.

Sain liked Radatz, and was furious when he learned that the Tigers had moved him out for a small sum of money.

Whatever the reason for the move, Radatz again lost his effectiveness after the transaction, prompting the Expos to release him in August. At the age of 32, the onetime relief star’s pitching career had come to an end.

Radatz remained out of baseball for much of his post-playing career, but he remained in touch with former teammates and the media, all the while earning a reputation as a humorous storyteller. An entertaining public speaker in his retirement years, Radatz often made appearances in which he delighted onlookers with stories from his days in Boston, Cleveland, Chicago and Detroit.

In 2003 and ’04, Radatz returned to the game as a pitching instructor for an independent minor league team in Lynn, Mass. He was come back for a third season on the job in 2005, but during the preceding winter, he suffered a bad fall at his home in Boston. Radatz hit his head, resulting in severe trauma. Paramedics were unable to revive him. Radatz was only 67.

Sadly, Radatz’ life was cut far too short, just as his pitching career had been so many years earlier. But for a brief while, a span that lasted three summers, Dick Radatz was as close to unhittable as any relief pitcher could be. And he was oh-so-colorful and distinctly memorable, a big but friendly man who cut a sizeable swath as The Monster.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame