- Home

- Our Stories

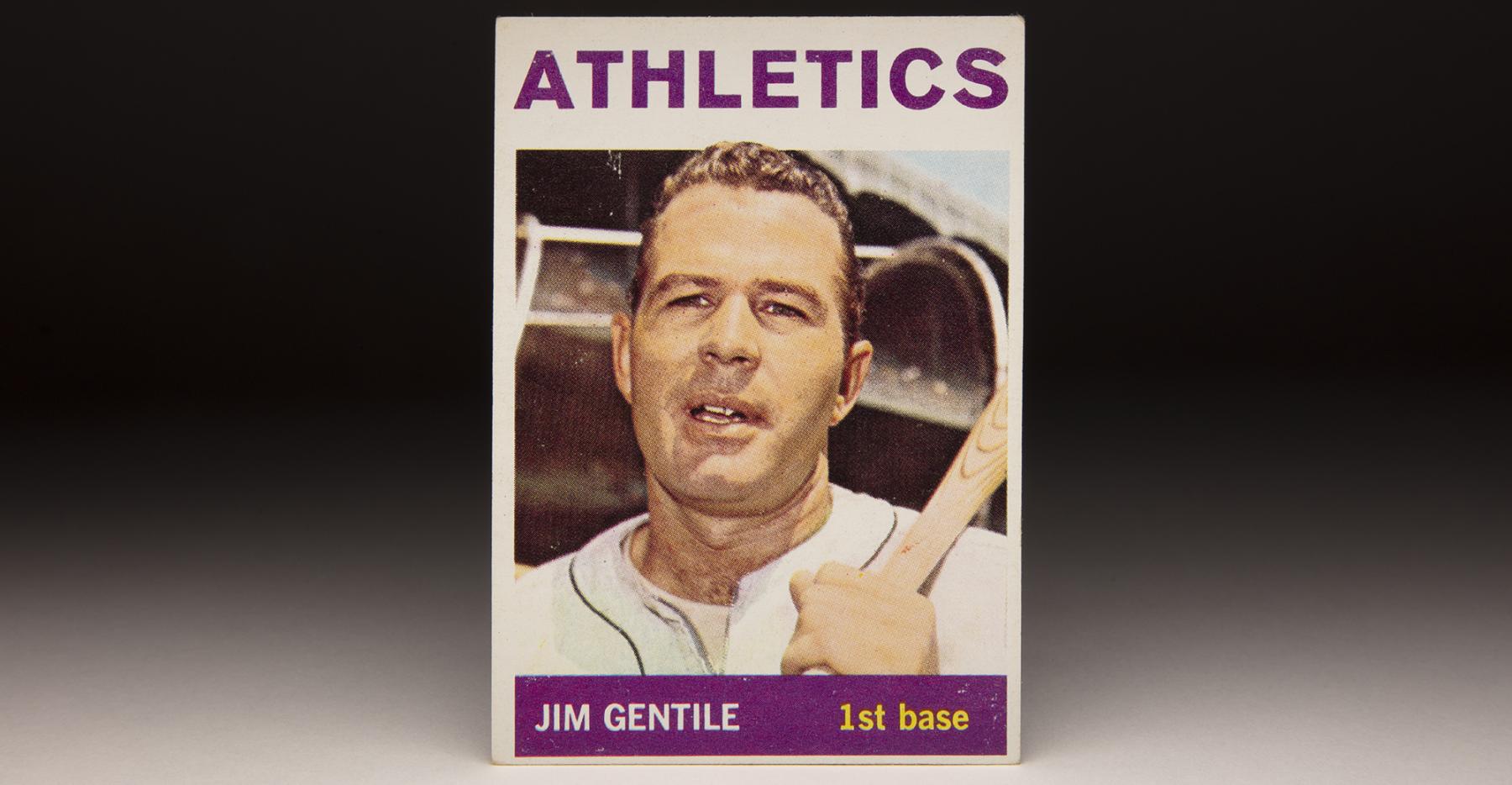

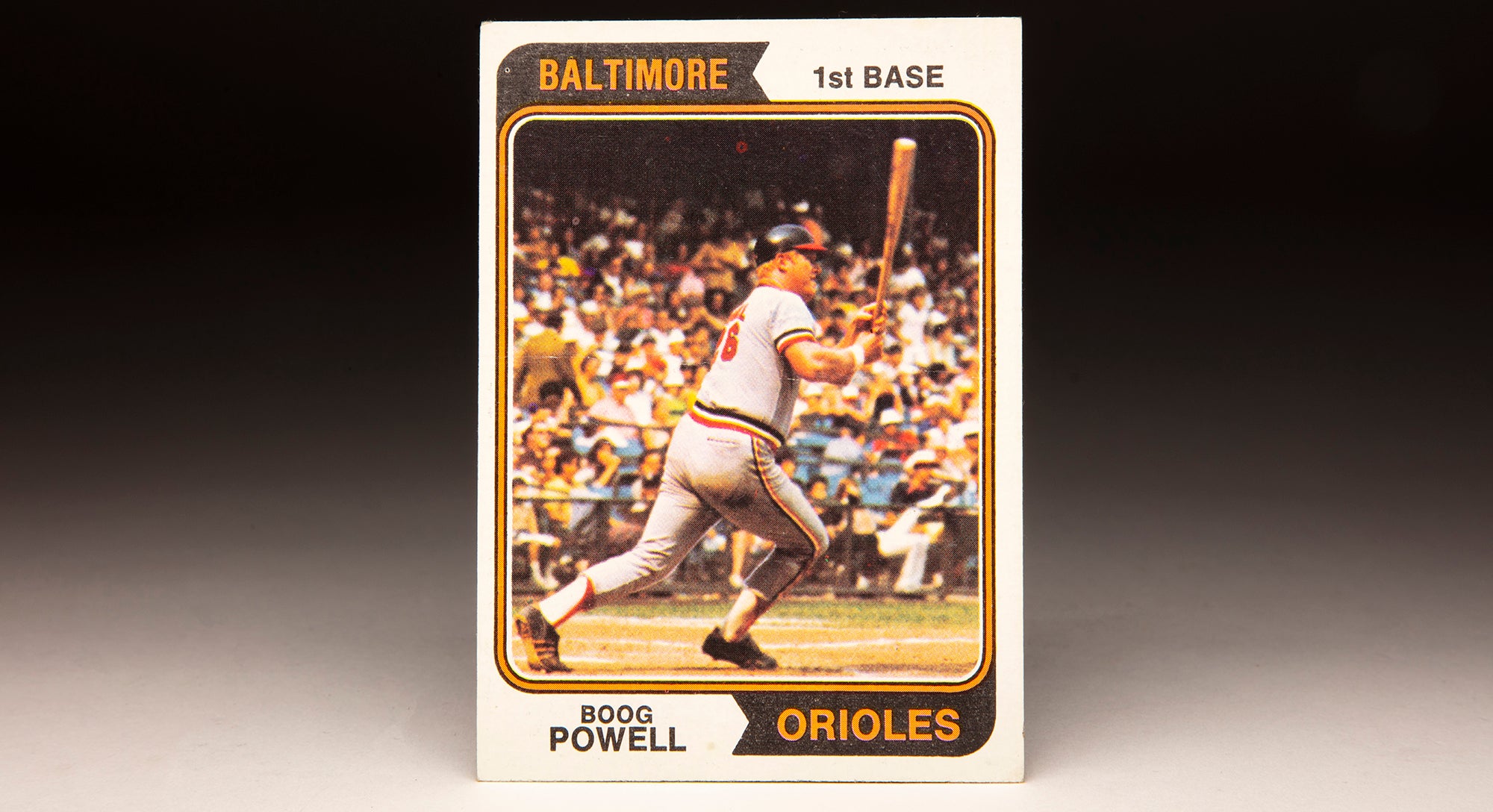

- #CardCorner: 1964 Topps Jim Gentile

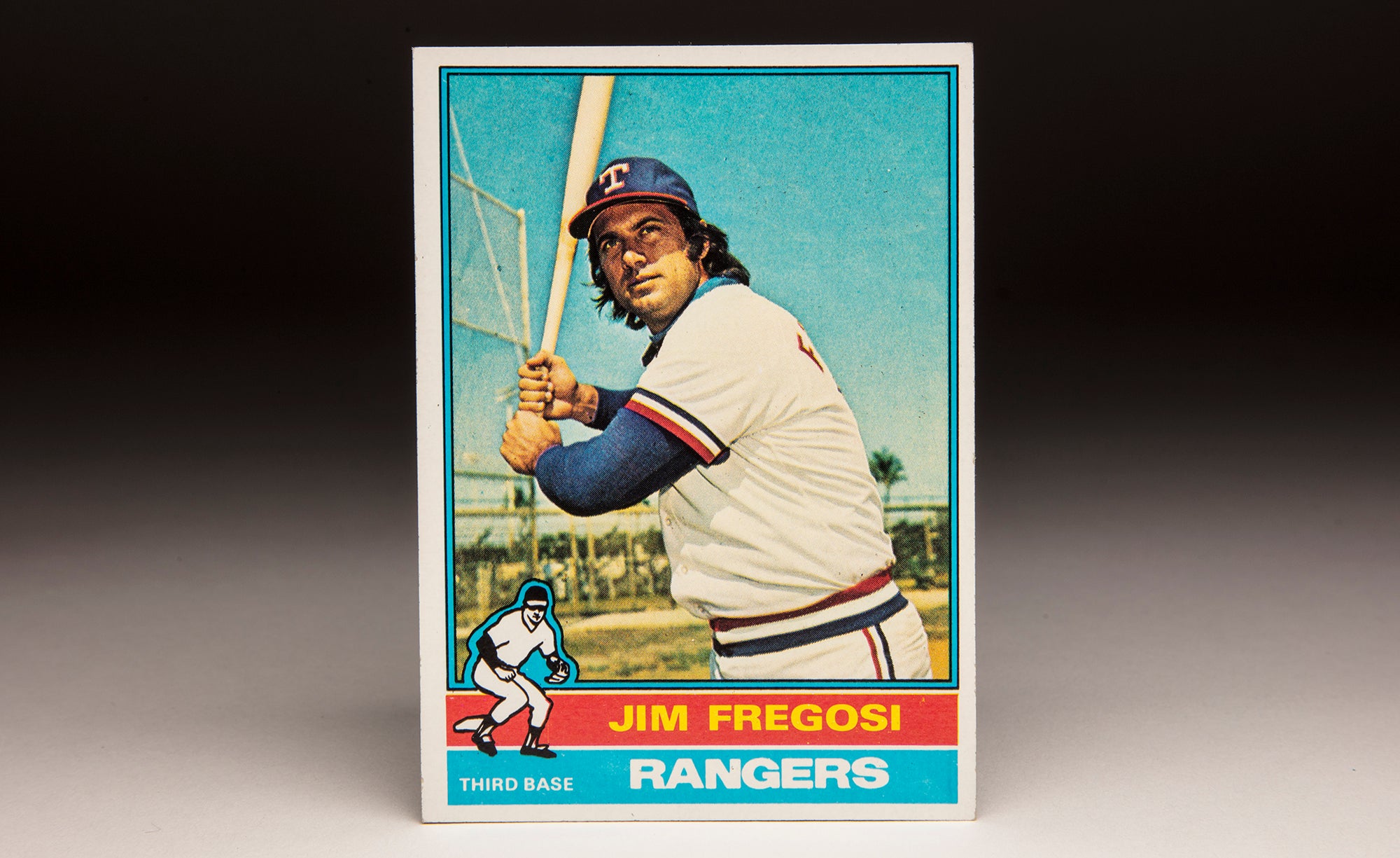

#CardCorner: 1964 Topps Jim Gentile

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

During the second season of M*A*S*H, a talented but romantically obsessed plastic surgeon named Stanley Robbins visits the 4077th to perform a nose job for one of the enlisted men. The doctor, played brilliantly by comedic actor Stuart Margolin, soon becomes sidetracked when he meets Major Margaret “Hot Lips” Houlihan, with whom he is immediately smitten.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“With a little work, you could have the jowls of a goddess,” Robbins says to Hot Lips. “I’m staying at Tokyo General. Just leave me a message – ‘Jowls.’ I’ll know.”

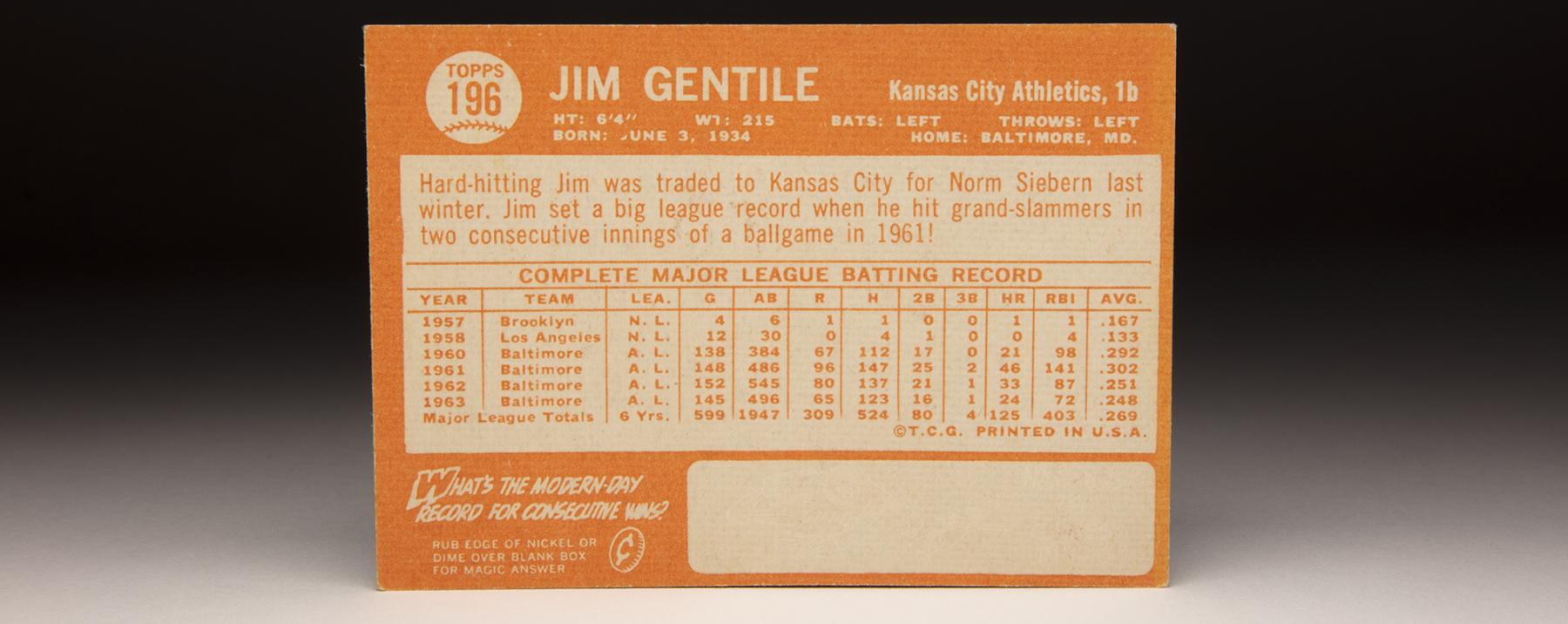

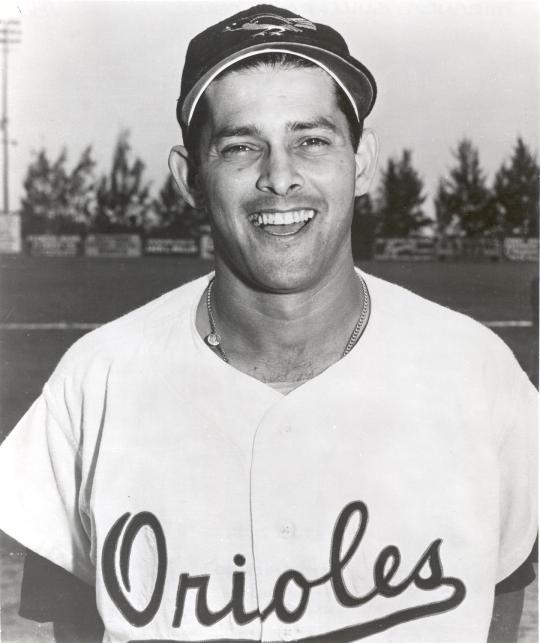

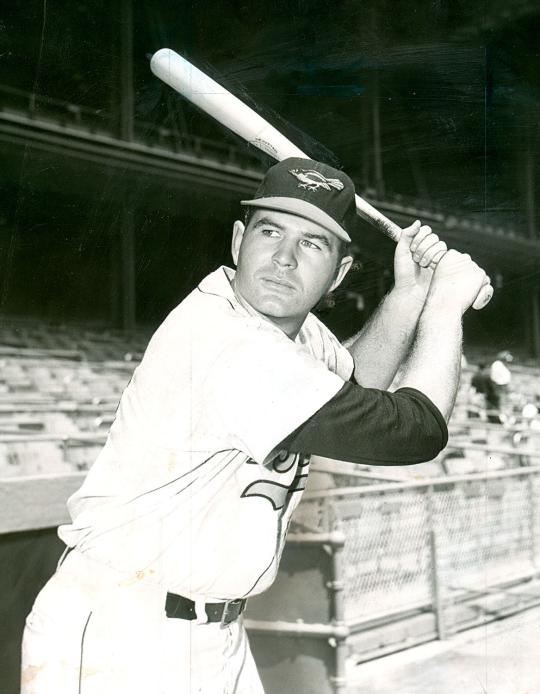

Well, for his part, former Kansas City Athletics slugger Jim Gentile had pretty good jowls, too, and they are on full display on his 1964 Topps card. With those strong jowls and chiseled chin, the rugged Gentile looked like he might have come straight out of central casting to play the part of a power hitter in a baseball movie. Of course, Gentile was a legitimate slugger in real life, as many American League pitchers discovered during the 1960s.

While I imagine a number of players did not like to take their caps off to pose for photographs back in the 1960s – if only because they revealed hair matted down by their caps, or in some cases, no hair at all – I don’t think that Gentile would have minded. Why wouldn’t he have enjoyed showing off that thick, curly brown hair, which only added to his he-man, strong-boy appearance? Then again, his lustrous hair had nothing to do with the decision to remove his cap for the photograph. That was an instruction from the Topps photographers, who were told to acquire capless shots of players who might be likely to change teams from one season to a next.

In Gentile’s case, the capless photo proved fortuitous. He spent the entire 1963 season, the year the photo was taken, hitting home runs for the Baltimore Orioles. When the Orioles traded Gentile to Kansas City after the season, Topps had the capless photo at the ready. The Topps design people slapped “Athletics” onto the bottom of the card, and no one (other than card-obsessed maniacs like this writer) would have even cared that he was actually wearing an Orioles jersey in the photo.

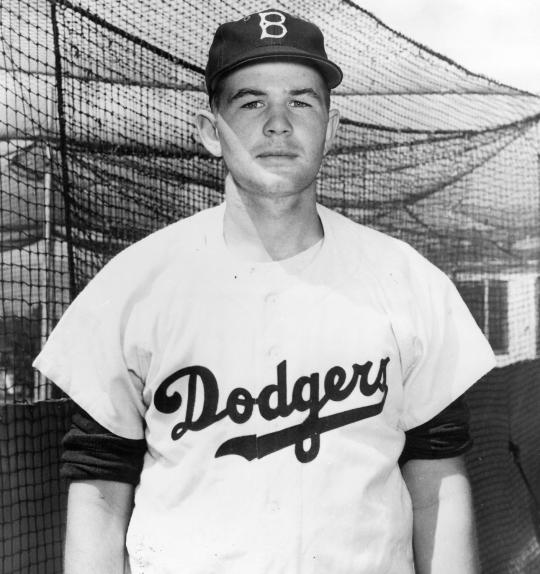

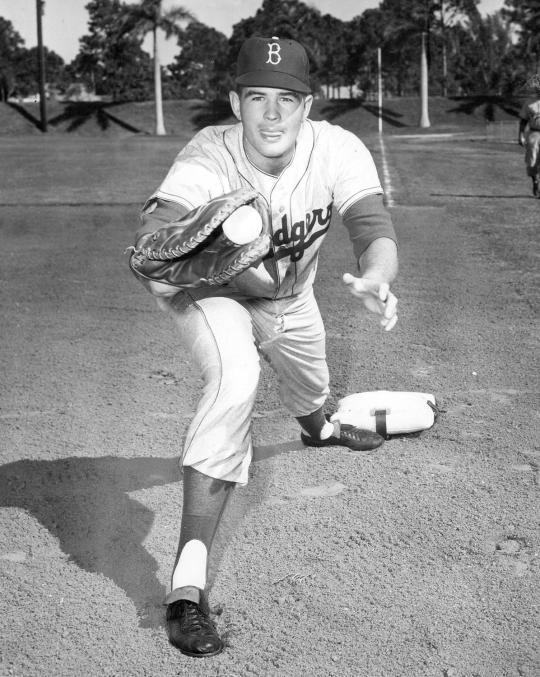

Somewhat ironically, Gentile’s professional career did not begin as a slugger – but as a pitcher. He had pitched and played the outfield as a high schooler, but the Brooklyn Dodgers liked his fastball and signed him to pitch prior to the 1952 season. They assigned him to Santa Barbara of the California League, where he put up respectable numbers in his rookie season.

Strangely, Brooklyn gave up on Gentile as a pitcher after that lone season. In 1953, the franchise shifted him to first base, assigning him to Pueblo of the Western League. The move turned out to be most fortuitous. The young left-handed slugger blasted 34 home runs, good enough to lead the league, while batting a reputable .270.

In 1954, the Dodgers assigned Gentile to repeat Pueblo. He continued to hit with power while raising his batting average to.318; that performance earned him a late-season promotion to Mobile of the Southern League. In 1955, Gentile posted huge numbers for Mobile. He then followed that up with a strong season in the Texas League in 1956, posting an OPS of 1.003.

After the 1956 season, Gentile accompanied the Dodgers on their goodwill tour of Japan. It was there that he received the nickname of “Diamond” from Dodgers catcher Roy Campanella, who referred to him as a “diamond in the rough.” “Diamond” went along beautifully with his first name of Jim. Thus, “Diamond Jim” was born.

During that tour of Japan, Gentile led the Dodgers with eight home runs. His torrid streak helped the Dodgers win 14 games on the tour while losing only four times. Based on that run, along with his terrific summer at Double-A, it was obvious that Gentile was ready for another promotion, this time to Triple-A. Playing for the famed Montreal Royals in 1957, Gentile hit 24 home runs, batted .275 and drew 73 walks.

Duly impressed, the Dodgers brought Gentile to Brooklyn at the tail-end of the 1957 season. He appeared in four games, giving him his first taste of the National League. He picked up only one hit in seven at-bats, but the sample size was so small as to be nearly meaningless. Perhaps more meaningful was the opportunity to play in the final game ever held at Ebbets Field.

As steadily as Gentile had progressed through the Brooklyn system, he faced a roadblock; the Dodgers already had a top-notch first baseman in Gil Hodges, who batted .299 with 27 home runs. Even at 33 years old, Hodges showed very few signs of giving up his stranglehold on first base.

With Hodges blocking his path, Gentile returned to Triple-A in 1958, the year the Dodgers relocated to Los Angeles. Other than a late-season cameo in LA, Gentile would spend most of the ’58 and ’59 seasons in Triple-A.

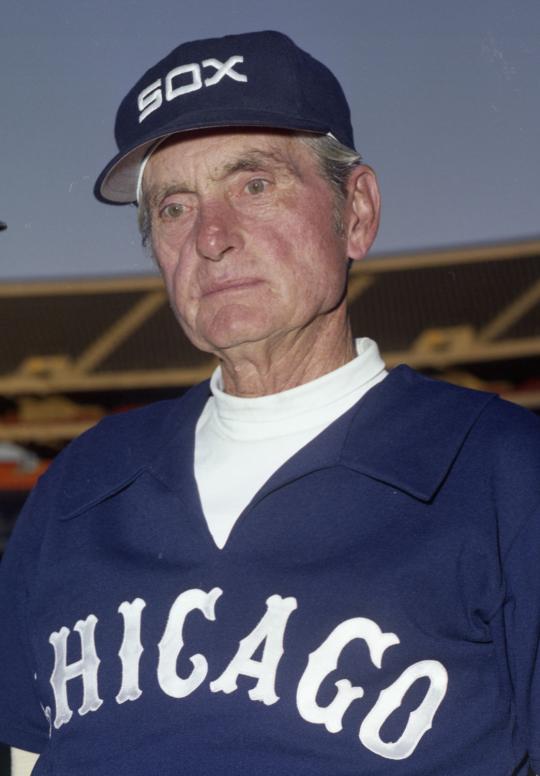

Realizing that Gentile was wasting away in Triple-A, the Dodgers began to place calls to other teams who might be interested in a power-hitting first baseman. One of them was the Chicago White Sox. At one point, Gentile said that general manager Buzzie Bavasi had informed him that a trade with the White Sox was a done deal, and that he should pack his bags and be ready for the next available flight. Gentile did as told, but the trade never happened. The Dodgers and White Sox could not agree on proper compensation coming back to LA for Gentile.

Finally, the Dodgers pulled the trigger on a trade after the 1959 season. In October, the Dodgers dealt Gentile, not to Chicago but to Baltimore for $50,000 in cash and two players to be named later, one of whom turned out to be slick-fielding shortstop Willy Miranda.

As it turned out, the deal between the O’s and Dodgers was conditional. If Orioles manager Paul Richards didn’t like what he saw of Gentile, the team had the option to return him to the Dodgers for the sum of $25,000. Gentile did not hit well that spring, to the point that he felt he was headed back to the minor leagues.

“The last day of Spring Training, I thought ‘I’m not going to make the team,’ ” Gentile told sportswriter Seth Tow in 2018. “There’s a [message] to go see Paul Richards. And I walked into the office to [see] him, and he just looked at me and said, ‘Son, you can’t be as bad as you look.’”

Believing that Gentile’s early play was not an accurate indication of what he could do, Richards stuck with his new first baseman, picking him over Boog Powell and Bob Boyd. Richards gave Gentile a month to prove he belonged. Richards’ patience would pay off. Platooning with veteran Walt Dropo, Gentile took over the left-handed part of the first base job, playing well enough over the first half of the season to earn selection to both of the midsummer All-Star games. By season’s end, the 26-year-old had compiled an impressive set of numbers (a .292 batting average, .403 on-base percentage, and 21 home runs) that placed him second in the league’s Rookie of the Year balloting (behind Ron Hansen).

As well as Gentile played in his rookie campaign, he would morph into stardom in 1961. Early in the season, he gave an indication of his ample power-hitting skills. Playing in a May 9 game against the Minnesota Twins, Gentile hit two grand slams – and then added a sacrifice fly for good measure. Gentile finished the game with nine RBIs, as the Orioles scored a 13-5 win against the Twins.

Gentile was just getting started. He would add three more grand slams to his total that summer, finishing the season with a record-tying five slams. His overall numbers were stunning: 46 home runs, a league-leading 141 RBI, a .302 batting average, 96 walks and an OPS of 1.069. In most seasons, Gentile’s level of production would have been good enough to earn the American League MVP, but in a season dominated by the home run-hitting exploits of Messers Mantle and Maris, Gentile had to settle for third place.

There is a theory in baseball that age 27 is the peak of a ballplayer. Gentile’s situation fully supported that theory. He had turned 27 in June of 1961, coinciding with his Herculean season. He would never again reach such lofty heights, though he was hardly a one-year wonder. Over the next three season, Gentile remained a productive and consistent player who specialized in hitting home runs and drawing walks. But Gentile felt his career was hurt by the Orioles’ change in managers. After the 1961 season, Richards had left to take the general manager’s job with the expansion Houston Colt .45s and was replaced by Billy Hitchcock.

Hitchcock urged Gentile to open up his stance and make more of an effort to pull the ball. Gentile tried, but the approach didn’t work. He then started tinkering with his stance, in an attempt to relocate his 1961 form. That would prove elusive.

Still, Gentile played solidly in 1962 and ’63. During the latter season, Sports Illustrated ran an article that accused Gentile and teammate Jackie Brandt of not always running balls out. For his part, Gentile felt the criticism was off base – he has continually maintained that he hustled throughout his career and that Hitchcock never fined him for not hustling – but the accusations may have factored into a decision the Orioles made in the offseason. That winter, the Orioles traded Gentile for a more athletic player who could fill in as an outfielder. That explained the one-for-one trade, Gentile-for-Norm Siebern, between the Orioles and Athletics.

Gentile gave the A’s what they wanted: Left-handed power. He hit 28 home runs, second best to Rocky Colavito on the Kansas City roster. But Gentile couldn’t pitch; the A’s had the worst pitching in the league, explaining why they won only 59 games and finished last in the American League.

Gentile continued to produce good power numbers for the A’s at the start of the 1965 season; in fact, he was tied with Mantle for the league lead in home runs when the A’s announced a trade. Now 30 years old and facing competition from a young Hawk Harrelson, who was emerging as the team’s first baseman of the future, Gentile became expendable. Making room for Harrelson, the A’s traded Gentile to the Houston Astros for pitcher Jesse Hickman and a player to be named later.

The Astros’ interest in Gentile stemmed from their general manager, Paul Richards, who had served as Diamond Jim’s first manager in Baltimore. But Gentile was a bad fit for the cavernous Astrodome, with its long dimensions and stale air, which suppressed the possibility of home runs. Gentile did not hit a single home run in the Astrodome over the balance of the season. With only seven home runs total and an OPS of .744, Gentile’s numbers proved underwhelming for the Astros.

In 1966, Gentile started the season in Houston, but ran afoul of manager Grady Hatton for losing his temper in a game; he smashed his bat into the ground and then flipped it in the direction of umpire Ed Vargo. In the past, Gentile’s temper had periodically created problems for him, but this was the first time it would result in a demotion.

“I decided my temper was not good for me when I got busted [for the Vargo incident],” Gentile later told writer Kathryn Spurgeon. “It about ended my career. That day, I sat alone in the clubhouse after everyone left and realized I was my own worst enemy.”

Embarrassed and regretful, Gentile reported to Triple-A Oklahoma City, where he remained until the franchise traded him to the Cleveland Indians for backup outfielder Tony Curry.

After the season, Gentile found work in the farm system of the Philadelphia Phillies. He played Triple-Ball in 1967 and ’68, but realized he had little chance of making it back to the major leagues. In 1969, he signed on with the Kintetsu Buffaloes of the Japan Pacific League. On Opening Day, he ruptured his Achilles tendon, the injury sidelining him for two months. When he returned to action, he found it difficult to adjust to the style of ball played in Japan. Finishing out the season, he returned to the states, but decided that the time was right to retire.

Leaving baseball, Gentile moved into the tire business, opened up a Midas Muffler store, and then returned to the game as an independent minor league manager. After five years of managing, and then a short stint as a coach, he opened up his own baseball camp in Chandler, Okla.

Gentile is in his mid-eighties now, fully retired from the game and living in Edmond, Okla. He still has most of that lustrous hair. And yes, those thick jowls are still in full evidence all these years later.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame