- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1967 Topps Lee Maye

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Lee Maye

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

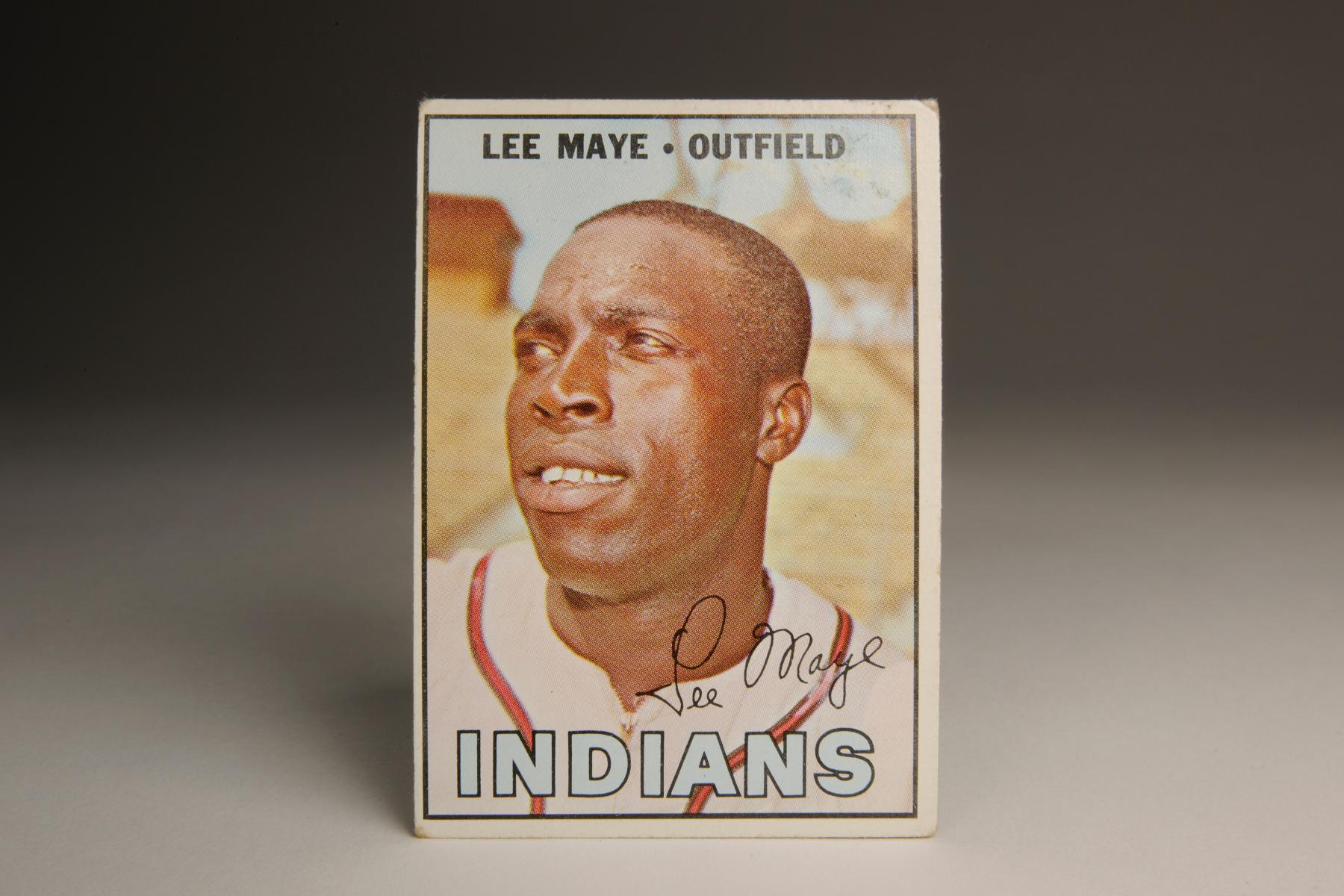

With simplicity comes beauty. That line of rationale could be used with the 1967 Topps set. The design is about as simple as one can get on a baseball card. The only graphics that Topps used on the front of each card are the blocked lettering for the player’s name, the thin black lettering for the team’s name - and that’s about it. Other than a small white border that is common to most sets, the rest of the card is devoted to the photograph itself. In terms of appealing to collectors, especially young children, making the photo space as large as possible is always a good path to take. That’s what Topps succeeded in doing with its 1967 set, and that, along with the generally crisp photography, is why this set remains a good one in the eyes of this collector.

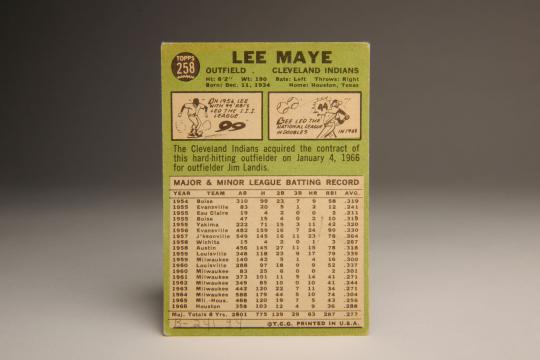

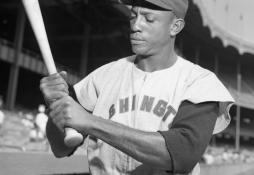

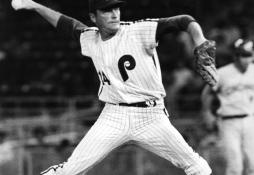

Lee Maye’s 1967 card indicates that he is now playing for the Cleveland Indians, even though his uniform colors dictate otherwise. In actuality, the red striping of the Milwaukee Braves, Maye’s former team, is clearly in evidence on this photograph. (Also notice the zipper near the collar, a feature that has become obsolete on major league uniforms.) Maye hadn’t played for the Braves since the spring of 1965, nearly two years earlier. By taking a photograph of Maye without a cap, as Topps often did with players in the 1960s and 70s, the company protected itself against the possibility of the player being traded. Maye was dealt twice in the interim, first by the Braves and then by the Houston Astros, who sent the outfielder to the Indians for catcher Doc Edwards, veteran outfielder Jim Landis, and left-hander Jim Weaver. So while the photograph is an old one, it does at least create the generic illusion of not being outdated.

As a younger fan, I might have been confused by Maye’s card for a different reason. That’s because I sometimes mistook Maye for a player with a similar name: Lee May, the power-hitting first baseman of the Cincinnati Reds and Astros who became known as “The Big Bopper.” Clearly, they were two very different people - and players. Maye, with an ‘e’ at the end of his last name, batted left and was a line-drive hitter with occasional power. May, without the ‘e,’ was a right-handed slugger through and through, and a player who gained far more fame during his career because of his prodigious power hitting for the early editions of the “Big Red Machine.”

That is not to say that Lee Maye was not well known. One could make the argument that, away from the ballfield at least, Maye was the more famous of the two similarly-named ballplayers. Maye made quite a reputation for himself as a professional singer. More specifically, he was the lead vocalist for a group called Arthur Lee Maye and the Crowns. (As a singer, Maye always used his given name of “Arthur Lee Maye,” as opposed to simply being “Lee Maye” in the baseball world.) At times, he also performed with The Platters.

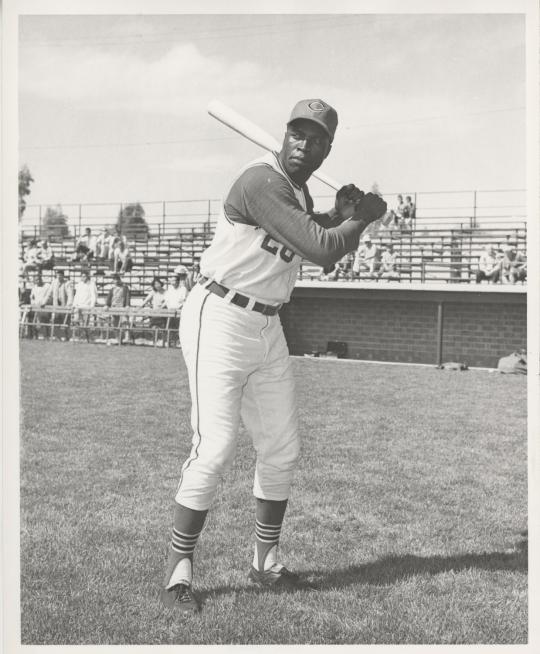

It was during his minor league days that Maye formed The Crowns, who came up with two hit songs, “Truly” and “Love Me Always,” in the mid-1950s. At the same time, Maye enjoyed matching success in the minor leagues. For Maye, baseball was his first love. Labeled a top prospect by the Braves for his incredible speed and smooth left-handed swing, he earned his first call-up to Milwaukee in 1959. Splitting both the 1959 and ’60 seasons between Milwaukee and the minor leagues, Maye managed to hit .300 for the Braves each summer. He also showed promise in right field, where his speed sometimes made up for his average throwing arm.

By 1961, Maye moved into the Braves’ starting lineup as a platoon right fielder. Maye played well, hitting a respectable .271 with 14 home runs and 10 stolen bases. But one wonders how much more he might have hit if not for a back injury that affected his swing.

The back injury, coupled with a respiratory illness, did more damage in 1962, lowering his average to .244 and diminishing his playing time and his power. Ever resilient, Maye bounced back in 1963, hitting .271 with 11 home runs and 14 stolen bases, before the recurring back injury forced him into the hospital.

Then came the career season of 1964. Feeling healthy, Maye batted a career-high .304, hit 10 home runs and led the National League with 44 doubles. Despite his sometimes spotty play in the outfield, the Braves made him their starting center fielder, stationed in between Rico Carty in left and Hank Aaron in right field. Able to avoid injuries, Maye played in a career-best 153 games.

Off the field, Maye found commercial success. His 1964 album, “Halfway Out of Love,” became a hit, selling over half a million copies. The notoriety of the album drew some attention from sportswriters, including noted baseball scribe Steve Jacobson. “I can sing anything, any style,” Maye told Jacobson in September of 1964. “I like rock n’ roll mostly, but I like what people are going to buy.”

While 1964 brought Maye money and attention, the season also had a disturbing overtone to it. Maye heard rumors about the franchise’s potential move to Atlanta. Outspoken on the subject of race relations, Maye expressed concerns about the possibility of playing in the South, where segregation persisted and where fans could make life difficult for Black players. “I just hope and pray we don’t go,” Maye told United Press International. “I don’t want to go there, but if the Braves go, I have to.” Maye had already seen plenty of racism while attending spring training in the South, and while playing minor league ball in Knoxville, Tenn.

Maye’s 1964 breakout gave every indication of stardom, but injuries and a wholly unexpected development derailed his career in 1965. Early in the season, Maye injured his right knee and ankle, forcing him to miss three weeks of action. Only one game after his return, the Braves shocked Maye by announcing a trade; the move sent Maye out of town as part of an effort to improve the Braves’ pitching. Maye went to Houston for knuckleballer Ken Johnson and reserve outfielder Jim Beauchamp.

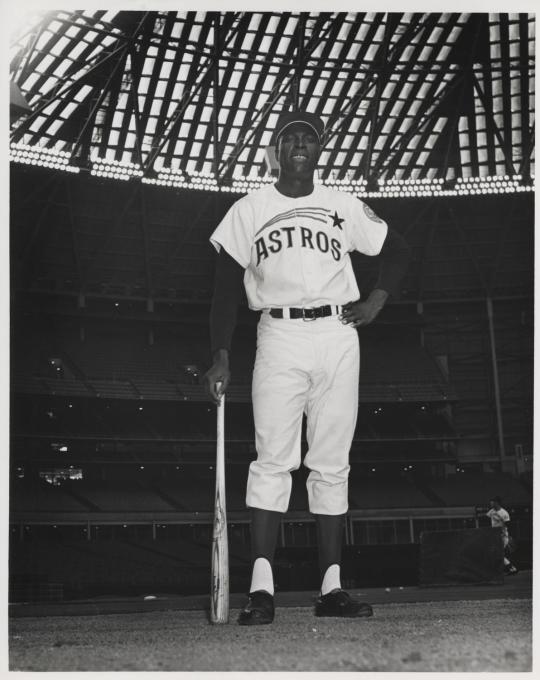

The trade might have been the worst development of Maye’s professional career; he felt betrayed, having to depart an organization he had known for more than a decade. Leaving a good team like the Braves, Maye joined a last-place Astros team that was still only three years removed from expansion. Maye also had to endure hitting in the Astrodome, an extreme pitchers park that minimized the offensive numbers of many Houston hitters over the years.

Predictably, his hitting suffered. Maye also found it difficult to track fly balls at the Astrodome, where the light-colored roof often obscured the baseball in midair. After two mediocre seasons with the Astros, the franchise dealt him to Cleveland. By now, Maye was in his early 30s and on the downhill side of his career. Showing little offensive improvement with the Indians, he departed them after two and a half seasons, sent to the Washington Senators for right-hander Bill Denehy and cash.

Maye put up good numbers over the balance of the 1969 season, hitting .290 with an .811 OPS. But that turned out to be a temporary bounce. A mediocre performance in 1970 resulted in the Senators placing him on late-season waivers. The Chicago White Sox picked him up, only to watch him struggle. In July of 1971, the Sox released Maye, ending his major league career. He latched on to the minor league Hawaii Islanders and played well there, but never received the call back to the major leagues.

Maye desperately wanted to stay in the game as a coach or a manager, but he could not find a single team willing to give him an opportunity. Some speculated that it was because of Maye’s outspoken nature and his occasional skirmishes with teammates. He wondered whether race was a factor in the repeated rejections he received, a legitimate question given that major league baseball would not feature a Black manager until 1975. The subject was a continuing source of frustration for Maye, who had earlier been critical of the lack of endorsement opportunities that came the way of African-American players.

With baseball out of the picture, Maye concentrated on his musical career. He became the lead singer of a group called The Country Boys and City Girls and also recorded songs as a solo performer. Needing a regular paycheck to supplement his sporadic musical income, he took a job with Amtrak as a baggage handler and food server, work that he did for 12 years before retiring.

Sadly, Maye developed pancreatic cancer in the early 2000s. The illness took him quickly; he died on July 17, 2002. In a strange coincidence, Maye died exactly 43 years to the day after making his major league debut for the Braves.

Maye died in relative obscurity, a rather unfortunate state of affairs given how much he achieved in both baseball and music, two difficult and competitive fields. He deserves to be remembered as one of the game’s most diverse talents, a speedy outfielder with a penchant for soul music and rhythm and blues. If not for injuries, Lee Maye might have achieved just such a legacy.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame