- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Dick Hall

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Dick Hall

I have no first-hand recollection of 1968 Topps; I was all of three years old when that set hit stores, and as much of a baseball fan as I’ve become, I don’t remember much – baseball or otherwise – from that time in my life.

In fact, I don’t think that I acquired my first 1968 Topps card until sometime in the 1980s, during a time when my love of cards rekindled after a few years of spending my spare time on stamp collecting.

It’s a shame that it took me so long to develop an appreciation for 1968 Topps. It really is an excellent set, highly underrated within the industry but one that is artistically well done. Perhaps the lack of appreciation stems from some of the photographs, which Topps had to re-use from earlier sets because of the boycott the Players’ Association imposed against the card company. By refusing to sit for new photographs, the players forced Topps to dip into its archive. Even if some of the photos are rehashes, the quality of the photography remained good against the design of the cards.

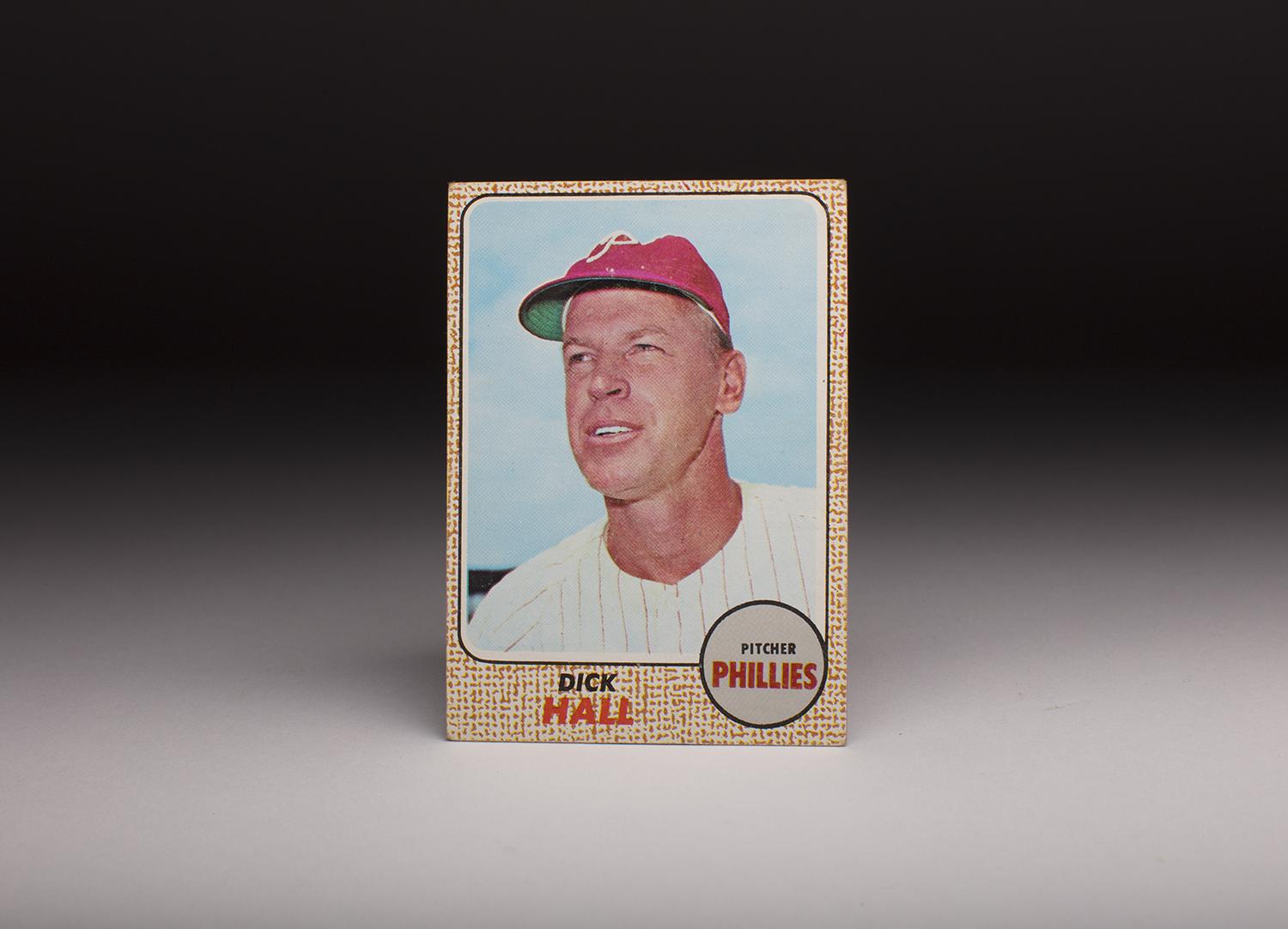

It’s really the design of the 1968 Topps card that has long caught my eye. Some have called this the set with the burlap borders. I prefer to call them speckled borders, but whatever you wish to call them, they look quite distinct from anything that has come before or after.

Orioles Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The unusual speckled borders, which look a little like 1960s kitchen wallpaper, also take away the flatness of the cards, giving them a three-dimensionality that is missing from other sets. I also like the yellow tinge on the backs of the cards.

The color scheme not only gives the cards a nostalgic 1960s feel, but it also makes the backs easy to read. No squinting is necessary when trying to read the short biographies or the cartoons on the backs of the cards.

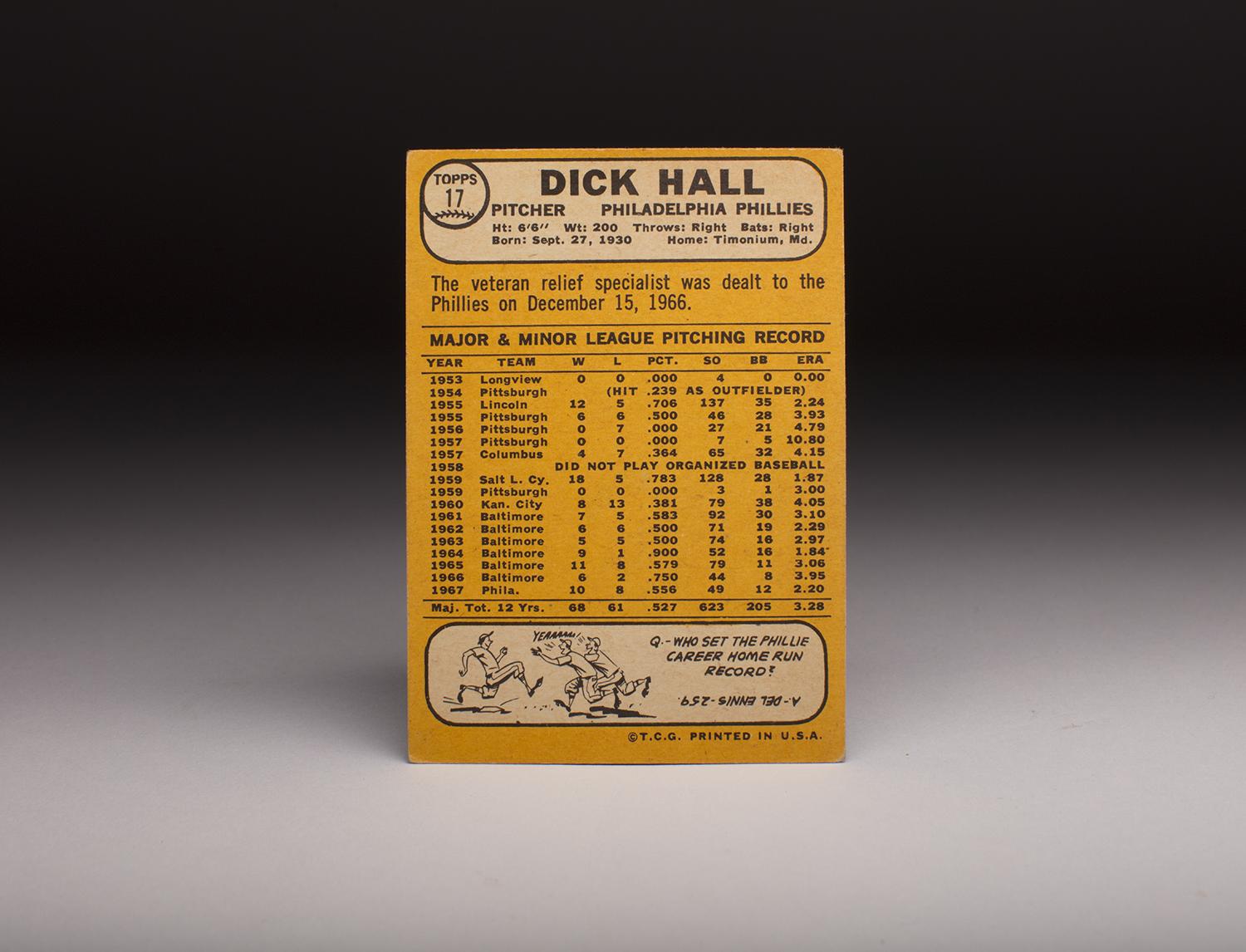

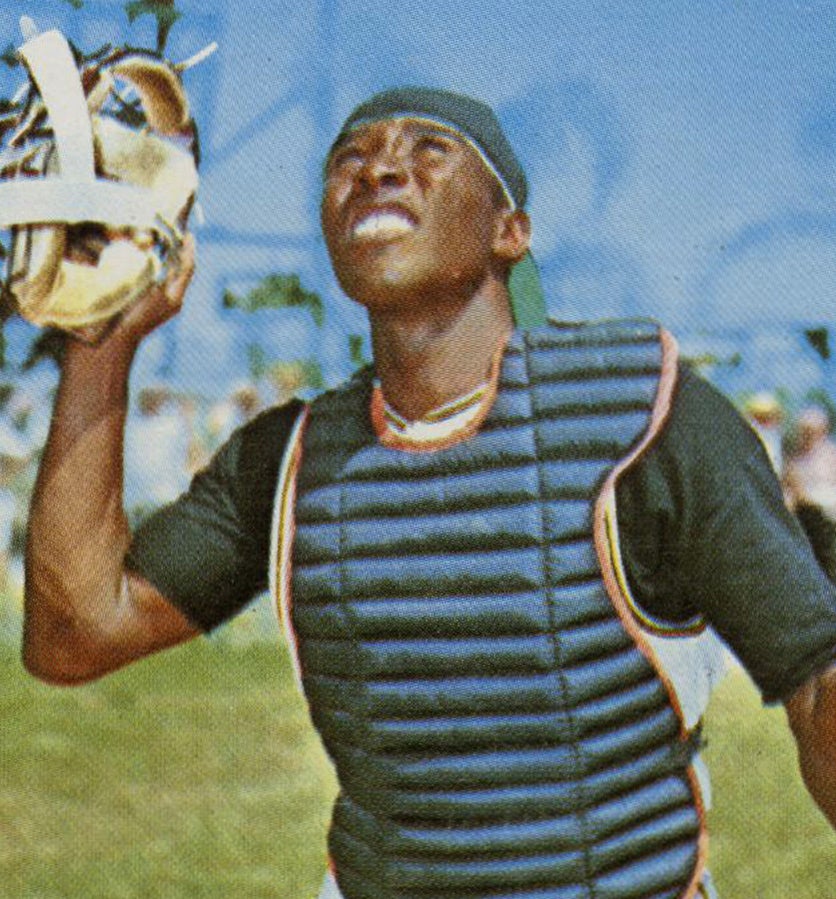

Of all the ’68 cards, one that jumps out for its basic simplicity, along with its ability to capture the unique look of the player, is the card of veteran reliever Dick Hall. The layout is pleasantly presented without clutter or intrusion, Hall’s bright white uniform and maroon cap set against a basic sky blue background, on what appears to be a gray day at the Philadelphia Phillies’ Spring Training site in Clearwater, Fla.

Then there is Hall himself. The veteran pitcher looks all of his 37 years on the card and bears a the trademark sunburn that often plagued players of that era (when more games were played in the daytime than now), but he still looks good, with his white teeth, clean cut hair, and no signs of paunch or weight gain on his face. Hall always kept himself in good shape, so his appearance here is no surprise. In contrast to his physical condition, Hall’s Phillies cap looks a bit well worn. Notice how his cap appears rumpled at the crown, as if it had been put through too many washing machines during a busy season in 1967.

More than his cap and his face, the most evident feature on the card is Hall’s neck, which is pronounced for its length. I remember two players from that era who were known for their especially long necks; one was Eddie Brinkman, the slick fielding shortstop with the Washington Senators and the Detroit Tigers, and the other was Hall. It’s no wonder that Hall earned the nickname “Turkey Neck,” which was often shortened to “Turkey.”

As Hall himself once said in an interview with Newsday, “The best description I’ve heard of what I look like on the mound is a drunken giraffe on roller skates.” Hall certainly looked odd when he pitched, but he also became one of the most efficient relief pitchers of the 1960s.

In making the major leagues, Hall took a non-traditional path. He attended Swarthmore College, a prestigious small school known for strong academics, but hardly a breeding ground for future professional athletes. A Division III college, Swarthmore has produced only six major leaguers, and none since Hall left the school in 1951. Hall thoroughly dominated the competition while at Swarthmore, earning letters in baseball, basketball, football, track and even soccer.

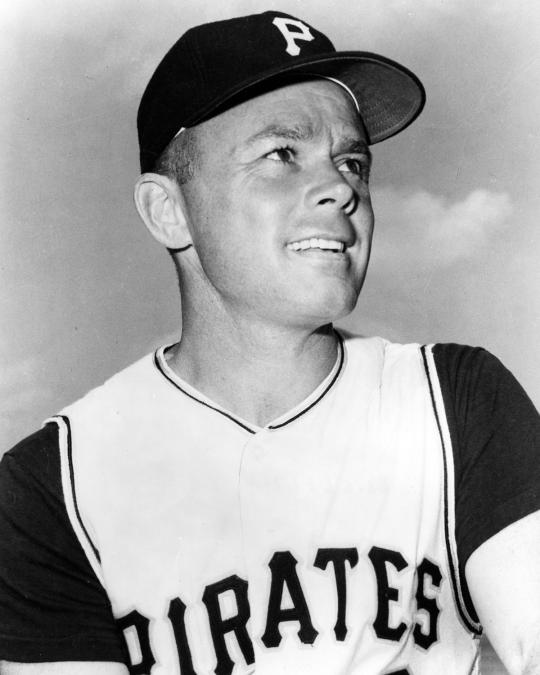

As an amateur ballplayer, Hall split his time between pitching and playing center field. Swarthmore played a limited schedule – less than 15 games, for academic and weather reasons – but Hall played so well that the scouts still found him. All 16 major league teams showed interest in the 6-foot-6 right-hander, but most of the clubs wanted Hall as a pitcher. The one exception was the Pittsburgh Pirates, run by the legendary Branch Rickey. “The Mahatma” envisioned Hall as a power hitter, so much so that he outbid all other teams, offering Hall a bonus of $25,000. Hall accepted the offer in September of 1951.

Although Rickey loved Hall’s speed and throwing arm, he and the Pirates faced a quandary: Where to play him? Over the span of three seasons, the Pirates tried him everywhere, including shortstop, third base, first base, center field, and right field. Hall didn’t seem comfortable at any of those positions. He also struggled to hit.

Without the benefit of minor league training, the Pirates brought him to the big leagues to start the 1952 season. Hall flopped. In 26 games, he batted .138 and failed to hit a home run. By May, it was obvious that he wasn’t ready. He was demoted to Burlington, the Pirates’ Class B affiliate in the Carolina League. Hall would receive two more cups of coffee in Pittsburgh over the next two seasons, first as a second baseman and then as an outfielder, but his continued flailings at bat convinced the Pirates that he simply couldn’t hit at an acceptable level.

In the winter that followed the 1954 season, Hall played for Mazatlán, a team in the Mexican Pacific Coast League. Hall had played in the league the previous winter, hitting 20 home runs in 80 games. Far more importantly, he had met his future wife, Maria Nieto, a native of Mexico. Now in his second season with Mazatlán, Hall married Maria in a New Year’s Eve ceremony.

Now fully conversant in Spanish, Hall told his manager, Memo Garibay, that he could not only play the outfield, but could also pitch. One day, when Garibay ran out of established pitchers, he took Hall up on the offer and put him on the mound. Hall pitched two shutout innings, looking so impressive that Garibay decided on the spot that his young right-hander needed to pitch fulltime.

Upon hearing reports of Hall’s success as a pitcher in Mexico, the Pirates came to agree with Garibay’s assessment. In the spring of 1955, the Pirates assigned Hall to Lincoln, Neb., one of their affiliates in the Class A Western League, with specific instructions to be used as a pitcher and left fielder. Hall promptly won 12 games, shot to the top of the league’s ERA leaders, and so dominated the Western League that the Pirates promoted him all the way to Pittsburgh in late July. Just like that, Hall became part of the Pirates’ starting rotation.

As an inexperienced pitcher, Hall featured mostly a fastball. Since he had no reliable breaking pitches, he had to locate his fastball in very specific areas of the strike zone, helping him to sharpen his control. In his major league debut against the Chicago Cubs, Hall spotted his fastball beautifully, striking out 11 batters. All in all, Hall pitched credibly in his rookie season, splitting 12 decisions, posting an ERA of 3.91, and walking only 28 batters in 94 innings.

It seemed like Hall had arrived, but arm problems ruined his next two seasons with the Pirates. Over that stretch, he failed to win a single game. Then in 1958, he developed hepatitis, which kept him out of action for the entire season. For the second time in his career, Hall faced a major crossroads.

Placed on the voluntarily retired list, Hall decided to pursue a business degree at graduate school. He seemed to think that his career, plagued by arm and health problems, might be coming to an end. Hall’s fears turned out to be ill-founded. In 1959, he returned to the active list, pitched at Triple-A, and earned the Pacific Coast League’s MVP Award. The Pirates rewarded him with a September promotion. He pitched well in one start and one relief appearance, but the Pirates decided to make a move with him that winter. In December, the Pirates traded Hall and two lesser players to the Kansas City Athletics for veteran catcher Hal Smith.

The trade prevented Hall from earning a World Series ring with the Pirates in 1960, but it turned out to be a godsend for him on a personal level. The A’s gave him 28 starts; Hall responded by winning eight games and posting an ERA of 4.05. The numbers weren’t eye-opening, but they were respectable. And for the first time in his career, Hall stayed on the major league roster from April through September without having to endure a trip to the minor leagues or the disabled list.

An even more significant break came Hall’s way in the spring of 1961. That’s when the A’s traded him to the Baltimore Orioles. That summer, the O’s used the 30-year-old Hall as a combination starter and reliever. He pitched well, posting a 3.09 ERA over 122 innings.

In 1962, the Orioles moved Hall to the bullpen on a regular basis and watched him blossom. He walked only 19 batters over 118 innings and lowered his ERA below 2.30. That marked the start of the prime segment of his career. Hall would become that rare player: Better in his thirties than he was in his twenties.

From 1962 to 1965, Hall posted ERAs of 2.28, 2.98, 1.85, and 3.07. Becoming a durable workhorse, he logged anywhere from 87 to 118 innings per season. He also displayed pinpoint control, rarely walking batters and not allowing even a single wild pitch. Although Hall no longer threw as hard as he once did, he could seemingly throw the ball exactly to a desired point in the strike zone. In particular, he became a master of working the outside corner.

In addition to impeccable control, Hall’s success stemmed from his conditioning – he was never overweight during his career – his high level of intelligence, and his deceptive, three-quarters delivery, which kept the ball hidden from opposing hitters, as it blended against the background of his uniform jersey. The tall right-hander threw what was termed a “rising fastball” (a pitch that didn’t actually rise, but maintained more of its height than the usual fastball), allowing him to induce weak pop-ups and routine fly balls.

Relying on movement and control, Hall did not show any slippage until 1966, when a bout with tendonitis affected his throwing arm. Seeing his ERA rise to 3.95, Hall became an afterthought. The Orioles completely bypassed him during their four-game World Series sweep of the Los Angeles Dodgers. Sensing that his days in Baltimore were numbered, Hall was not surprised when the O’s traded him that winter, sending him to the Phillies for a player to be named later.

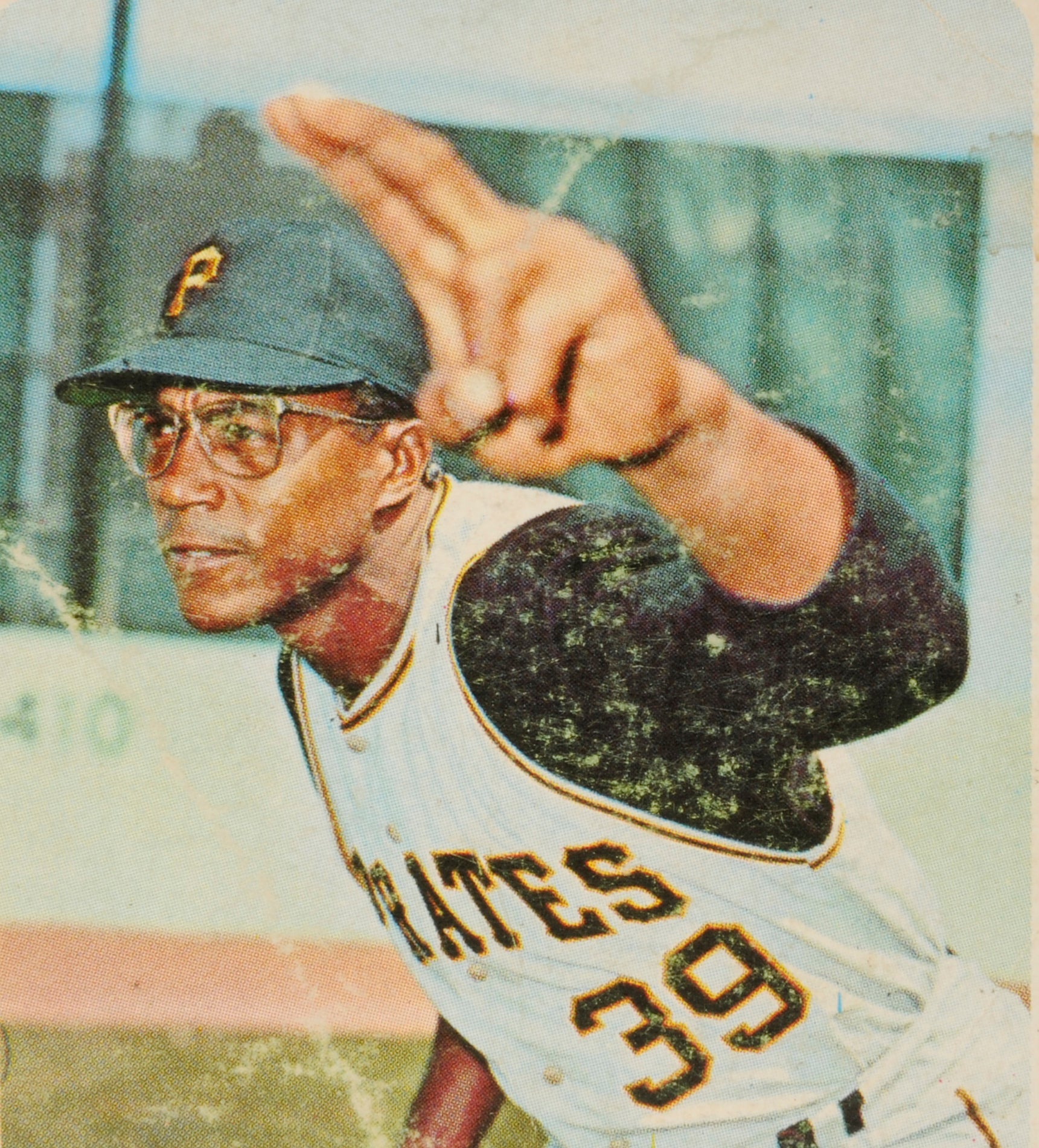

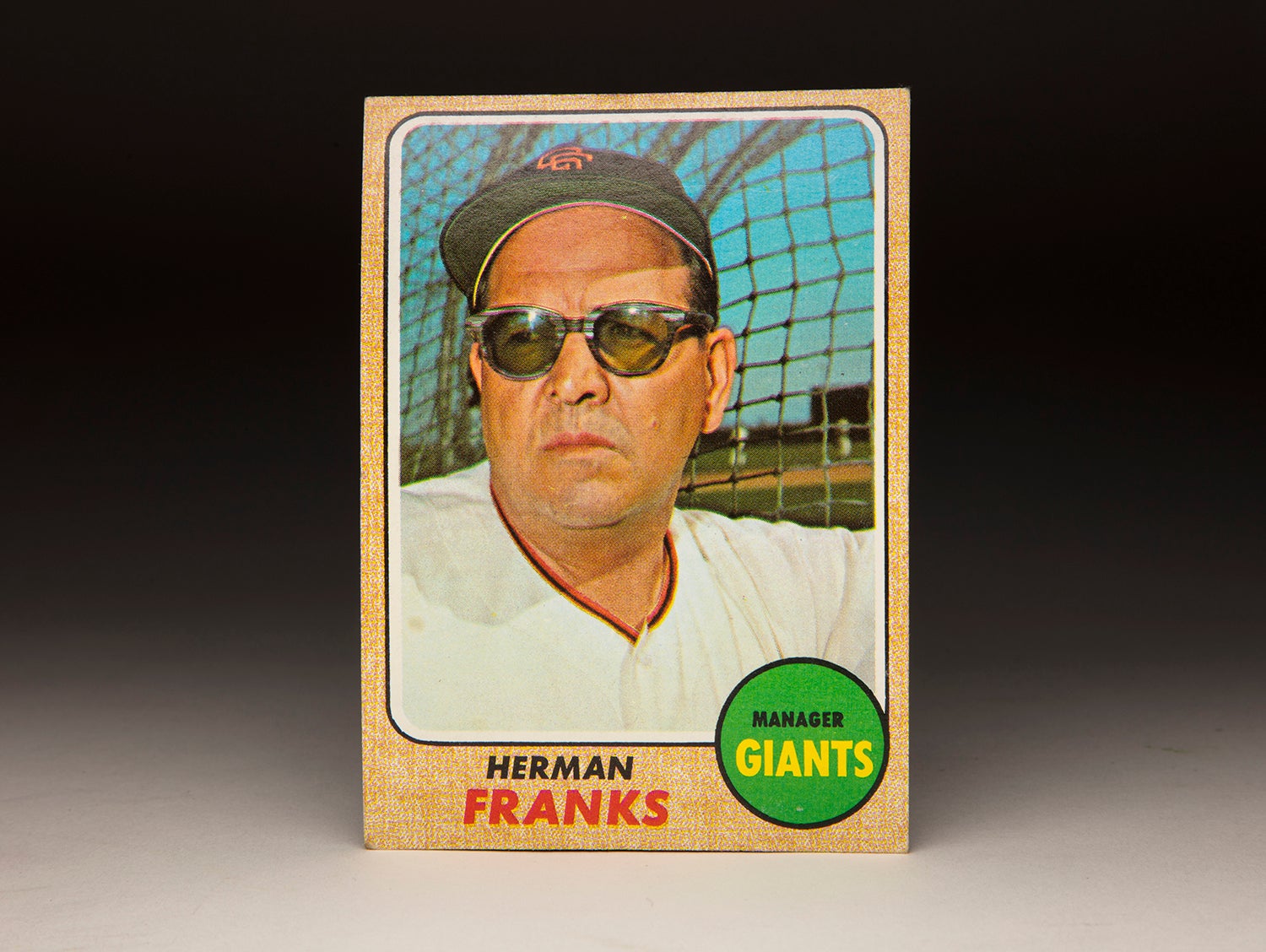

After Dick Hall earned a spot on the Baltimore Orioles' 25-man roster, manager Earl Weaver (pictured above) came to rely on Hall, integrating him into a bullpen that helped the Orioles win three straight American League pennants from 1969-71 and the 1970 World Series. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

It was a trade the Orioles would regret. Hall bounced back sharply in 1967, putting up a 2.20 ERA for the Phillies and occasionally receiving chances to close out games. He also made an emergency start in place of Jim Bunning on June 15; Hall not only pitched well, but fired a complete game win against his former team, the Pirates.

The following season did not go nearly as well for Hall. He came up with a sore elbow, which resulted in his ERA rising to 4.89. After the season, the Phillies released Hall. At 39, he seemed to have reached the end of the line. Hall didn’t give up. He placed a call to Orioles general manager Harry Dalton, who offered him a non-guaranteed Spring Training invite for 1969. Hall accepted the make-good deal, promptly pitched 11 shutout innings, and earned a spot on the Orioles’ 25-man roster. Manager Earl Weaver soon came to rely on Hall, calling on him to pitch in more and more high-leverage situations. By season’s end, the 39-year-old Hall had lowered his ERA to 1.92, second only to Eddie Watt among Baltimore relievers.

In contrast to 1966, Hall finally received his chance to pitch in the postseason. He made a scoreless appearance in the first-ever American League Championship Series, and then delivered another scoreless outing in the World Series, even as the Orioles lost the Fall Classic to the underdog New York Mets. Hall’s late-career effectiveness continued in 1970. He won 10 games in relief, buttressed by a 3.04 ERA. That summer, Earl Weaver praised Hall for his intelligence and his ability to maintain a mental scouting report on every hitter.

“He’s a machine,” Weaver told Ed Rumill of the Christian Science Monitor. “He’s an IBM, a human computer. He has a built-in file on every opposition hitter and he never forgets.”

Hall more than justified Weaver’s faith in the postseason, too. In Game 2 of the ALCS, he shut out Minnesota over four and two-thirds innings to earn the win. And then in Game 2 of the World Series, Hall pitched the final two and a third innings against Cincinnati’s “Big Red Machine,” a lineup that included Pete Rose, Johnny Bench, and Tony Perez. Hall’s Herculean effort saved the game and gave the Orioles a 2-0 Series lead. For their part, the Reds didn’t seem to understand how they couldn’t hit Hall – or what exactly he was throwing.

“He’s got that funny motion,” Perez told the Baltimore Sun. “He throws a change-up or a palm ball. I don’t know what it is.”

Whatever the pitch, Perez and the rest of the Reds could do little against with the 40-year-old Hall. Returning to the Orioles for the 1971 season, Hall finally started to show his age. His regular season ERA rose to nearly 5.00, and rather remarkably, he also threw the first – and only – wild pitch of his career. Yet, he did salvage the season by saving a game for Jim Palmer in the World Series. Hall then retired, leaving the game with a 3.32 ERA, compiled over a span of 20 seasons.

Equipped with his business degree and a passing grade on his CPA test, Hall left baseball altogether and became a fulltime accountant, something he had already undertaken on a part-time basis during his playing days.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital & outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum