- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Manny Sanguillen

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Manny Sanguillen

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

When I was growing up way back in the 1970s, the word “cool” was exceedingly popular. Anything that was good was described as “cool.” Everything that was not good was referred to as “not cool.” As you can see, we extracted plenty of mileage from that simple, four-letter word.

Unlike a lot of pop culture slang from the 1970s, “cool” is still used today. It’s not as popular as it once was, but I hear a lot of folks younger than me use the word, perhaps even more than people of my generation do. It’s clearly not just an outdated 1970s word or phrase, like “groovy” or “far out” or “catch you on the flip side,” but one that has become part of our culture’s lasting lexicon.

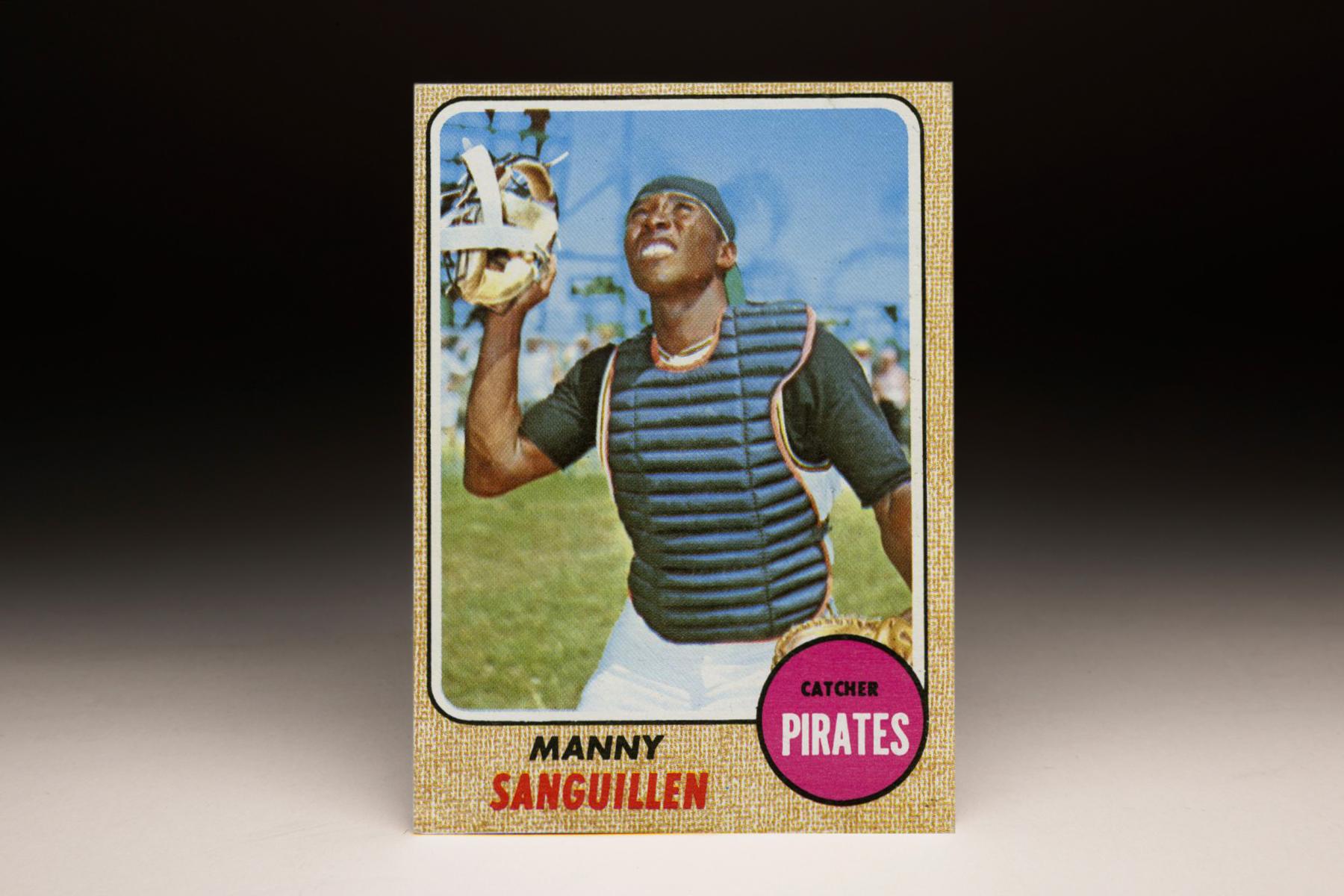

Baseball cards, in my mind, are always cool. They were cool 40 years ago and they are no less so today. Of course, some cards are cooler than others. When I see Manny Sanguillen’s 1968 Topps card, these words come immediately to mind: “This card is very cool.” There is just so much to like about it.

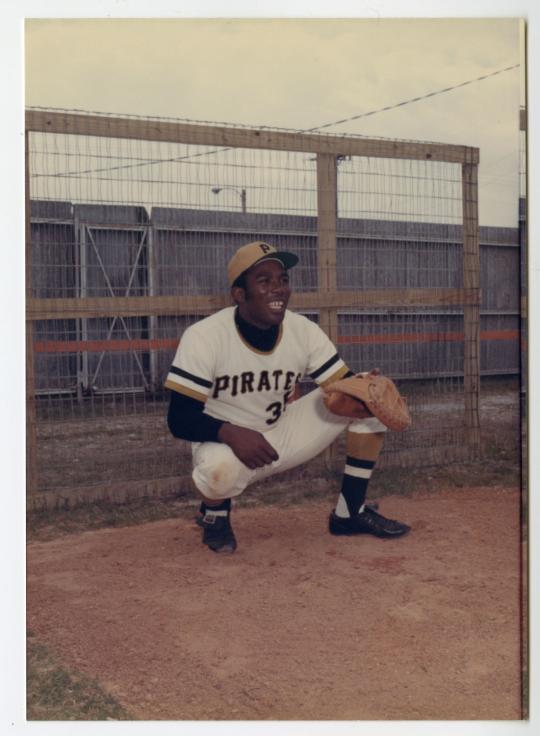

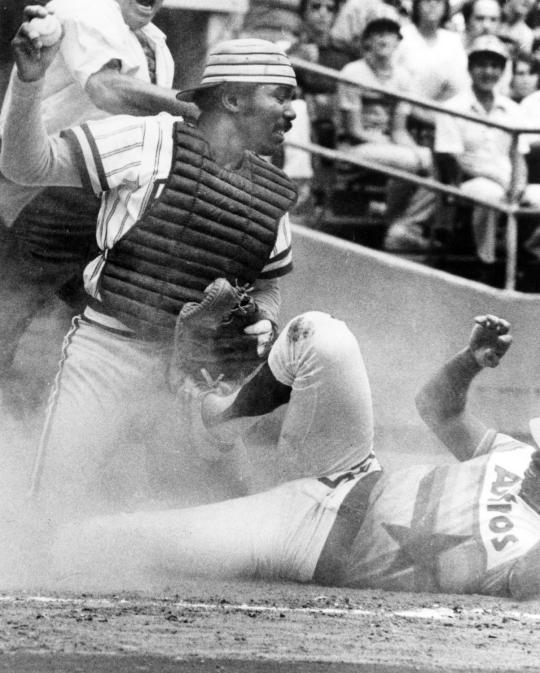

First, we see Sanguillen in his full catching regalia, complete with chest protector and catcher’s mitt, though the cropping of the photo makes it impossible to determine if he’s sporting shin guards. He is wearing his cap backwards, as all catchers do when they take their places behind the plate. Clearly, the photo doesn’t depict actual game action, but Sanguillen is doing his best to recreate the situation under the setting of Spring Training in Bradenton, Fla. Having ripped off his mask, he squints as he looks skyward into the spring sun, pretending to track an imaginary pop-up. It’s a pretty realistic pose from Sanguillen, a good acting job from a player who has been asked to play pretend. If Topps had airbrushed a crowd in back of Sanguillen here, we might have believed that this photograph was taken during a real live game. Maybe.

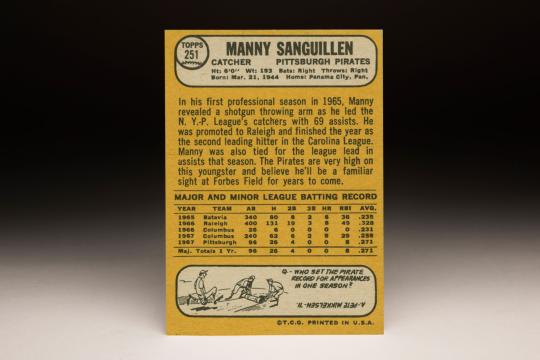

There’s also a bit of incongruity to the card. Topps issued this card in 1968, but that was the one year from 1967 to 1980 that Sanguillen did not play in the big leagues. After debuting for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1967, when he batted .271 in 30 games, the Bucs anticipated that he would make the Opening Day roster in ’68. Instead, he lost out to a pair of other young catchers, Jerry May and Carl Taylor, and went back to Triple-A Columbus, where he spent the entire summer. Thankfully, Topps didn’t lose the faith, publishing another card for Sanguillen in 1969, when he became the club’s No. 1 catcher.

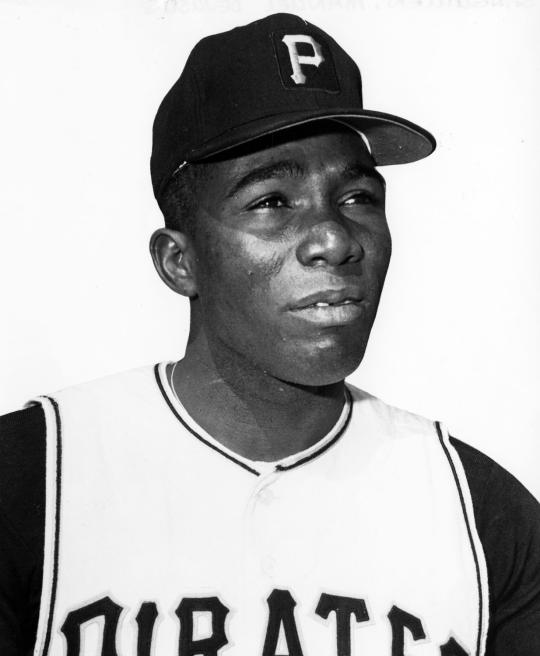

At one point, it seemed unlikely that Sanguillen would even pursue a career in professional baseball. As a youth growing up in Panama, he was a talented boxer. He also enjoyed playing soccer and basketball. But it was his ball-playing ability that made a fan of Pirates scout Herb Raybourne, who saw Sanguillen play one day in the Panamanian Winter League. After watching Sanguillen play, Raybourne recommended that he become a full-time catcher, and told the Pirates’ head of scouting Pittsburgh to step up efforts to sign the youngster.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Raybourne’s initial faith in Sanguillen paid off by 1969. That spring, Manny battled Jerry May for the starting catching job. Pirates manager Larry Shepard liked Sanguillen’s game, but felt that his limitations in speaking English hurt his work with the Pirates’ pitching staff. Sanguillen not only won the catching job that spring but also worked hard to improve his English. “That was why one of the first things I bought when I came to the United States was a dictionary,” Sanguillen told Pittsburgh Press reporter Bill Christine.

Sanguillen caught 129 games that summer and showed an aptitude for putting bat on ball. He hit .303, hit line drives to all fields, and played well defensively, taking charge of a Pirates pitching staff that featured older veterans in Bob Veale and Jim Bunning and two younger pitchers in Steve Blass and Dock Ellis.

One of the highlights to Sanguillen’s season came on Sept. 20, when Bob Moose pitched a no-hitter against the New York Mets. Sanguillen skillfully handled the pitch-calling duties that day, helping Moose mix in a knuckleball with a sinking fastball. With efforts like that, Sanguillen’s reputation as a handler of pitchers grew immensely. He also honed his reputation for throwing out base runners that summer, nailing 44 percent of opposing runners in 1969.

Sanguillen’s overall game, while a major positive force for the Pirates, exhibited deficiencies in other areas. He showed almost no patience at the plate, drawing only 12 walks. He also hit with little power, reaching the seats only five times. These weaknesses would remain part of his game for the rest of his career. A scouting report of Sanguillen, both good and bad, would remain mostly the same for the bulk of his career.

That’s not to say that Sanguillen didn’t play better in 1970. He raised his batting average to .325 in 1970, while also showing slight improvement in his ability to hit home runs and triples. The baseball writers certainly took note. At season’s end, they gave him some voting support in the National League MVP race. Sangy finished 11th in the balloting, ahead of his two far more famous teammates, Roberto Clemente and Willie Stargell.

Off the field, Sanguillen made one of his most important life decisions when he married Kathy Swanger of North Versailles, Pa. Almost from the beginning, Sanguillen heard comments about the marriage - and not in a good way. Some people asked him why he was married to a white woman; others whispered it among themselves.

The bigoted comments about his marriage seemed to have little effect on Sanguillen’s on-field performance. In 1971, Sanguillen would virtually duplicate his production from 1970, but recognition from fans and the quality of his team both increased. Now generally regarded as the second-best catcher in the league (behind a fellow named Johnny Bench), Sanguillen was selected for the All-Star team. His play behind the plate and his consistent line-drive stroke helped the Pirates win the National League East and the pennant, as the franchise returned to the World Series for the first time since 1960. Though overshadowed by the great Clemente, Sanguillen batted .379 in the Series, helping the Pirates pull off a remarkable upset of the Baltimore Orioles.

Sanguillen also took part in some history that season. On Sept. 1, the Pirates hosted the Philadelphia Phillies at Three Rivers Stadium. That day, manager Danny Murtaugh filled out a lineup that featured nine black players, either of African-American or Latino descent. Sanguillen was part of that lineup, the first one of its kind in MLB history.

Sanguillen enjoyed another .300 season in 1972, only to see the Pirates lost the fifth and final game of the National League Championship Series against the Reds on Moose’s wild pitch. Sanguillen felt he should have done a better job blocking the pitch, but the ball was well outside, and took a nasty short-hop bounce before bounding past Sanguillen. In reality, it would have taken a miraculous block to keep the ball in front of him and prevent George Foster from scoring the pennant-winning run.

The wild pitch became a trivial matter by comparison that winter. Sanguillen’s best friend on the Pirates, Roberto Clemente, boarded a small DC-7 on New Year’s Eve as part of a mission of mercy to earthquake-ravaged Nicaragua. Sanguillen was supposed to be aboard the flight, too, but he misplaced his car keys in his winter league apartment. Unable to find his keys, Sanguillen had no way of making it to the airport in time. A few hours later, Sanguillen learned that the plane had crashed, and that all five men aboard the plane, including Clemente, were presumed dead.

While Sanguillen’s life had been spared by happenstance, he was devastated by the loss of his friend, who was only 38. Sanguillen didn’t want to merely mourn Clemente, but became determined to find him, thinking that there was a small chance he was still alive. At the very least, Sanguillen wanted to locate his remains. For three days, Sanguillen dove into and swam through the cold, shark-infested waters near the location of the plane crash. An excellent swimmer, Sanguillen made his way through underwater caverns, hoping to find Clemente’s body. Finally, after a search expedition uncovered the badly damaged remains of pilot Jerry Hill, Sanguillen gave up his own search efforts.

Reminders of Clemente persisted into Spring Training. When the Pirates reported to Bradenton, they decided to give Clemente’s locker to Sanguillen. The Pirates’ organization meant well by the gesture, but it put additional pressure on Sanguillen to try to replace Clemente within the clubhouse.

As the Pirates prepared for the 1973 season, they had to find a replacement for Clemente in right field. Believing that prized prospect Dave Parker was not ready, manager Bill Virdon decided to make a double switch. He made Milt May, the Pirates’ talented backup catcher, the No. 1 receiver and simultaneously shifted Sanguillen to right field, Clemente’s former post. The Pirates had experimented with Sanguillen as an outfielder in the past; with his speed, athleticism, and strong throwing arm, they believed Manny could handle the position on an everyday basis.

At the time, teams rarely consulted players about position changes. Generally speaking, the manager told the player where to play, not the other way around. Sanguillen went along with the move, but he did not really want to play right field. In a way, Sanguillen felt guilty about trying to play a position that his friend had once called him. “I really feel bad,” Sanguillen told Sports Illustrated, “because we miss him so bad. I don’t like to talk too much about him.”

Still, Sanguillen took his place in right field on Opening Day. He would remain there for roughly two months. In 53 games, Sanguillen committed six errors, a staggering total for an outfielder. Realizing that Sanguillen was not comfortable, Virdon wisely cut the cord on his experiment. On June 15, the manager made Gene Clines his right fielder and moved Sanguillen back to catcher.

Except for an occasional appearance in the outfield, Sanguillen would remain behind the plate for the rest of the season. Perhaps distracted by the shifting of positions, his batting fell off that summer, down to .282. His on-base percentage, thanks to only 17 walks, fell to .301, the worst mark of his career.

Such free-swinging ways would become a legendary trademark of Sanguillen’s career. Outside of one season, he never drew more than 28 bases on balls in a year. If a pitch was anywhere near the strike zone, he usually offered at it. He would swing at pitches that were as high as his helmet, and as low as his shoetops. At least once in his career he hit a pitch on the bounce and smacked it into the outfield for a single. If Eddie Yost was “The Walking Man,” then Sanguillen was “The Swinging Man.” “Thou shalt not pass,” became the refrain of a few play-by-play announcers in describing Manny’s philosophy as a hitter.

Sanguillen also used an unusually heavy bat. He preferred a bat that weighed 40 ounces, in contrast to the bats of most other players, which generally fall in the area of 30 to 34 ounces. Most batters would have difficulty swinging a 40-ounce model, but the strength in Sanguillen’s wrists and arms made it an ideal fit.

With his large bat and never-ending strike zone, Sanguillen would somehow make contact - and hard contact - more often than most hitters. He would remain with the Pirates through the Bicentennial year of 1976, peaking with his Herculean performance in 1975. That’s when he batted a career-high .328, drew a whopping (for him) 48 walks, and compiled an OPS of .842. Sanguillen’s efforts won him a place in the All-Star Game, along with some consideration for MVP.

Pirates fans had already come to love Sanguillen for his ever-present smile (made distinctive by the large gap in his front teeth), his willingness to talk to anyone, and his joyful way of playing the game. They appreciated him even more that summer, with his batting average pushing .330 and his reputation climbing as one of the game’s elite catchers.

At 31, Sanguillen had reached the peak of his career. Historically, catchers do not age well, and Sanguillen was no different. No one should have been surprised when his hitting fell off considerably in 1976, but the Pirates became doubly concerned when injuries limited him to 114 games. Now believing that he could no longer catch regularly, the Pirates made a controversial decision that winter. They traded him, not for another player, but for a manager, Chuck Tanner of the Oakland A’s. Some Pirates fans, already upset about the loss of a popular player, thought the team had lost its mind trading Sangy for a field manager.

Splitting his time between catching, the DH role, right field, and first base, Sanguillen spent all of 1977 with the A’s. He put up a .275 batting average, which was 15 points lower than his 1976 mark. Oakland owner Charlie Finley, realizing that Sanguillen was no longer a star worthy of his large salary, traded him back to the Pirates that winter.

Sanguillen became a backup during his second stint with the Pirates. He played sparingly behind the team’s other catchers, Ed Ott and Duffy Dyer, while also putting in some time at first base. Sanguillen would remain a reserve over the next two seasons, playing mostly as a backup to Willie Stargell, the starting first baseman. He did enjoy one last hurrah with the Pirates in 1979. Inserted as a pinch-hitter in Game 2 of the World Series, Sanguillen lined a single to right field, scoring Ott with what proved to be the game-winning run. A few days later, Sanguillen celebrated his second world championship with the Pirates.

After the 1980 season, the Pirates dealt Sangy to Cleveland as part of the deal for future Hall of Fame right-hander Bert Blyleven, but he never played a game for the Indians. Only a few days after Spring Training, Sanguillen received his release. Sanguillen felt it was time to retire and return home to Pittsburgh.

Since then, Sanguillen has endured some troubles, including a failed business venture and bankruptcy. But he’s now found a new niche, running a barbecue stand at PNC Park in Pittsburgh. Sanguillen is a familiar sight on most game nights, chatting up fans, shaking hands, and signing autographs for those who remember his glory days in the 1970s.

All these years later, Sanguillen remains as popular as any living Pirate, a near legendary figure within both the neighborhood and the baseball community. Manny Sanguillen is still as cool as they come, just as cool as his 1968 Topps card.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Card Corner Footnotes

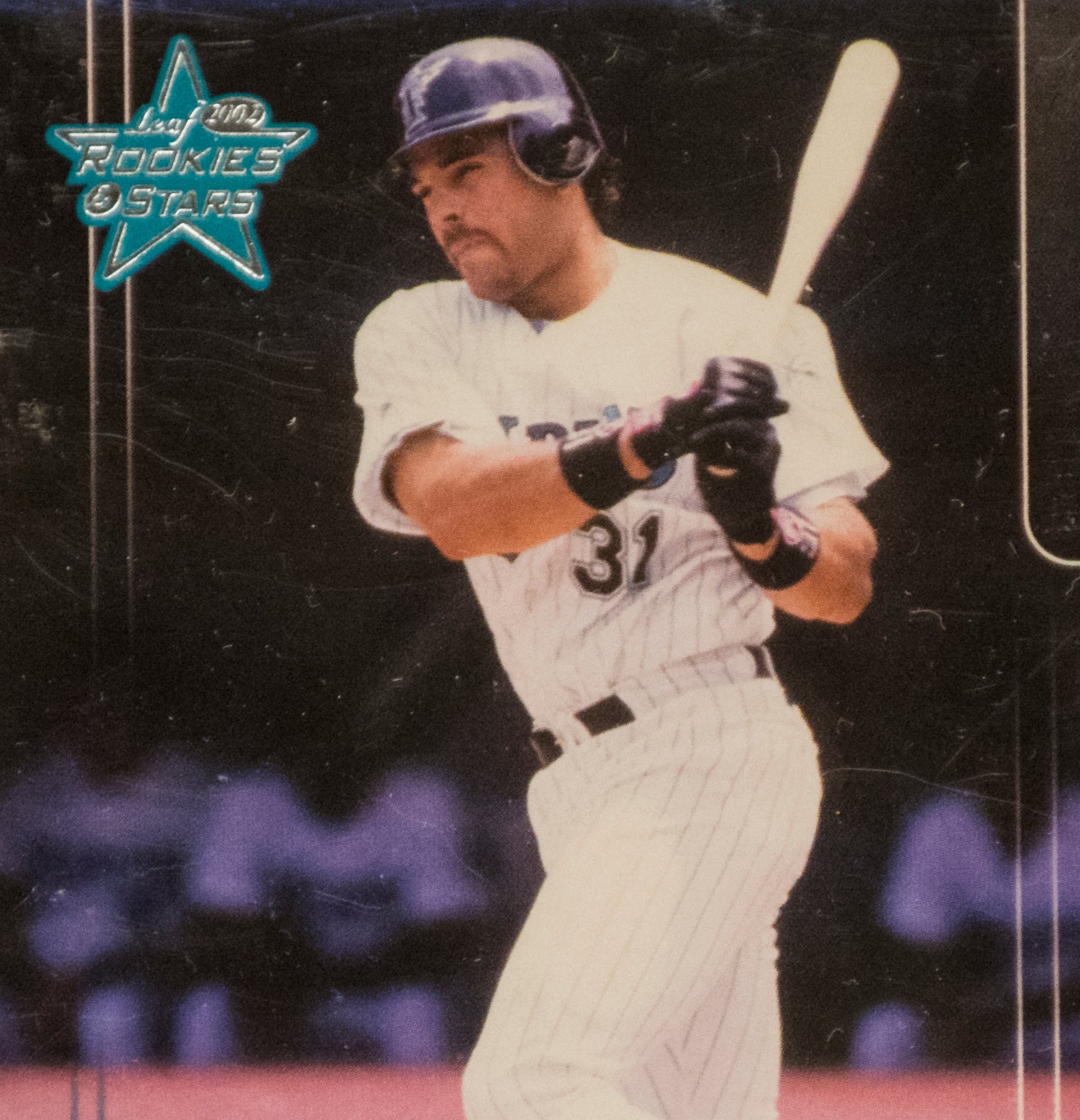

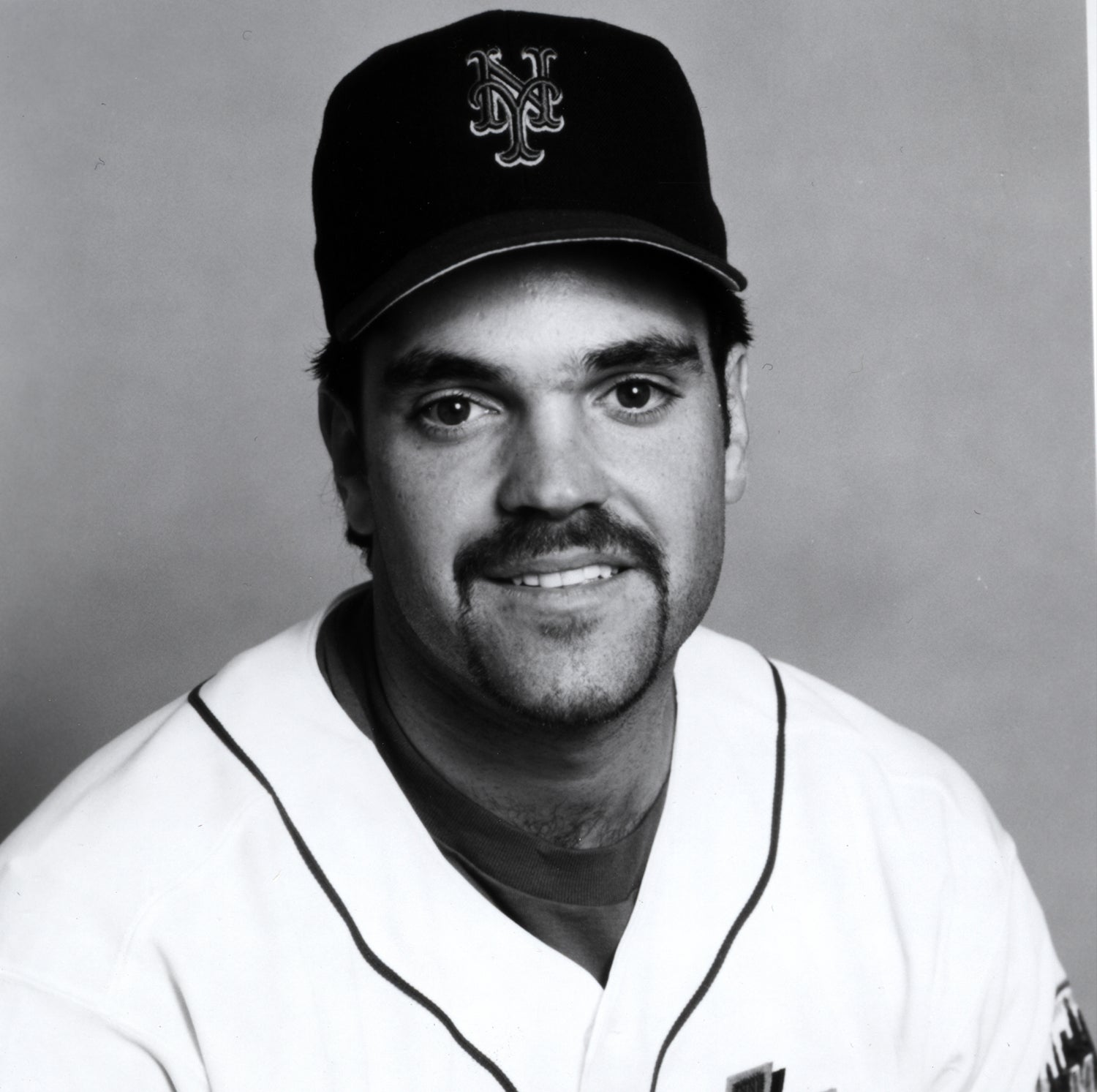

While Sanguillen was one of the game’s best catchers of the early 1970s, a Hall of Fame catcher is making some card-related news in 2016. Mike Piazza, Hall of Fame Class of 2016, is featured on more than a dozen different Topps “Bunt” cards, which are digital versions of baseball cards.

On Saturday, August 6, Piazza electronically signed a number of these digital cards at the National Collectors Convention in Atlantic City. “It’s kind of cool and different,” said Piazza. “It’s unique and I’m really into the technology. It’s fun and continuing to revolutionize the industry.”

The Topps Company will be offering a variety of these digital signature cards over the next week. To learn more about these special digital Mike Piazza cards, visit Topps Apps.