- Home

- Our Stories

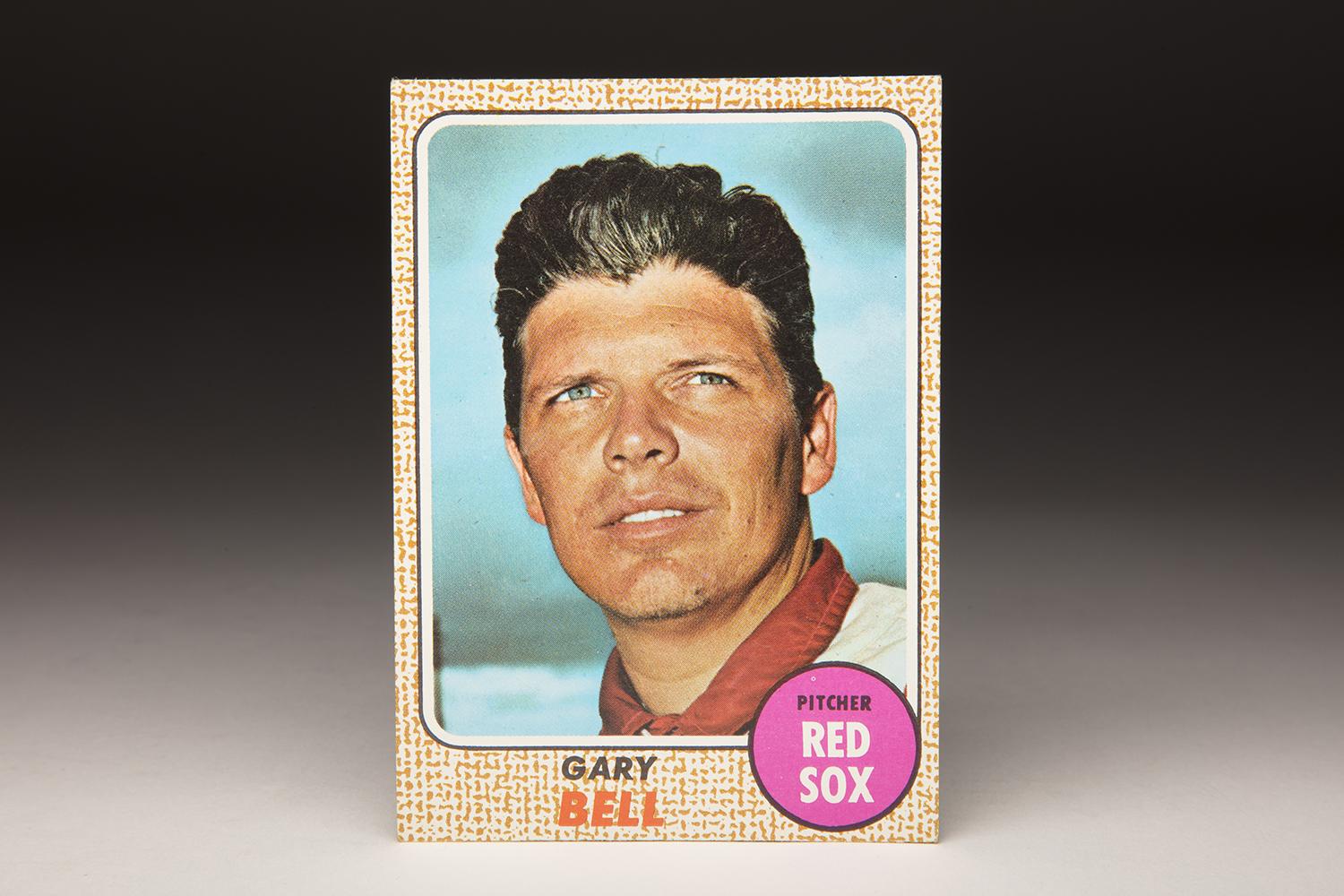

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Gary Bell

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Gary Bell

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

There’s a good reason why some ballplayers are reluctant to take off their caps in posing for photographs. Consider the case of former San Diego Padres catcher/first baseman Gene Tenace.

For years, Tenace balked at taking his cap off for team photographs. Some people who worked for the Padres couldn’t understand why. And then they realized that Tenace, who had been fighting a battle of the hairline for years, was bald. Well, that pretty much solved that mystery.

Back in the 1980s, there were at least two players I remember who rarely seemed to be caught with their caps off. I suspect that they did this intentionally. One was Steve “Bye Bye” Balboni. The other was Toby Harrah. One day, while watching the New York Yankees’ pregame show on WPIX-TV, I happened to notice Balboni in the background, with his cap off. The view left me in shock. With his long sideburns, I had always assumed that Balboni had plenty of hair. But he didn’t. Well, he had plenty of hair on the sides of his head, but none on the top. Basically, he was bald.

The same could be said of Toby Harrah, who also had a fair amount of hair on the sides. With a cap on, Harrah and Balboni looked like they had hair to spare. With a hat off, the results of male pattern baldness could clearly be seen.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Now let’s consider the case of Gary Bell, a pitcher of 1960s vintage. I’m guessing that Bell expressed little reluctance at posing for a baseball card without his cap on. Bell possessed a beautiful head of hair, thick and dark and lustrous, and complete with a low hairline. When it comes to ballplayers and their hair, few could have outdone Bell during his 1960s heyday. Frankly, he should have been doing commercials for hair spray, or other assorted hair products.

Bell’s 1968 Topps card provides curiosity on other fronts. It is likely that the photograph was taken during the 1966 season, or perhaps even earlier, when Bell was still pitching for Cleveland. In 1967, Topps met with resistance from many major league players, who were unhappy with their baseball card compensation and had been told by union head Marvin Miller not to pose for updated photographs until a new agreement had been reached with Topps. Bell was one of the players who apparently refused to pose for a new photo when Topps visited the Boston Red Sox in the middle of the ’67 season. As a result, Topps had no other resource but to dip into its archive, find Bell in a capless shot, and resurrect it for use as part of the 1968 set.

This is why you will see many old photographs, including capless ones, featured in Topps sets in 1968 and ’69. Topps and the Players Association finally reconciled late in 1968, too late to help the 1969 set, but in plenty of time to create new photographs for the 1970 set.

By 1970, Bell was done as a major leaguer. His pro career began a decade and a half earlier, when he signed as an amateur free agent out of San Antonio College prior to the 1955 season. A right-hander with an excellent fastball and plus stuff, Bell drew the interest of numerous teams, including the Boston Red Sox and New York Yankees. Bell received good offers from both teams, but opted to sign with a third club, the Cleveland Indians. The reason? Bell felt that the Indians’ starting pitching staff was aging, creating opportunities to move up quickly.

Bell turned out to be right. He moved up steadily within the Indians’ minor league system, graduating to Cleveland within three years. He was playing golf one day with his minor league manager in Seattle, Catfish Metkovich, when the skipper received a phone call. The message: Put Bell on the first plane to Cleveland.

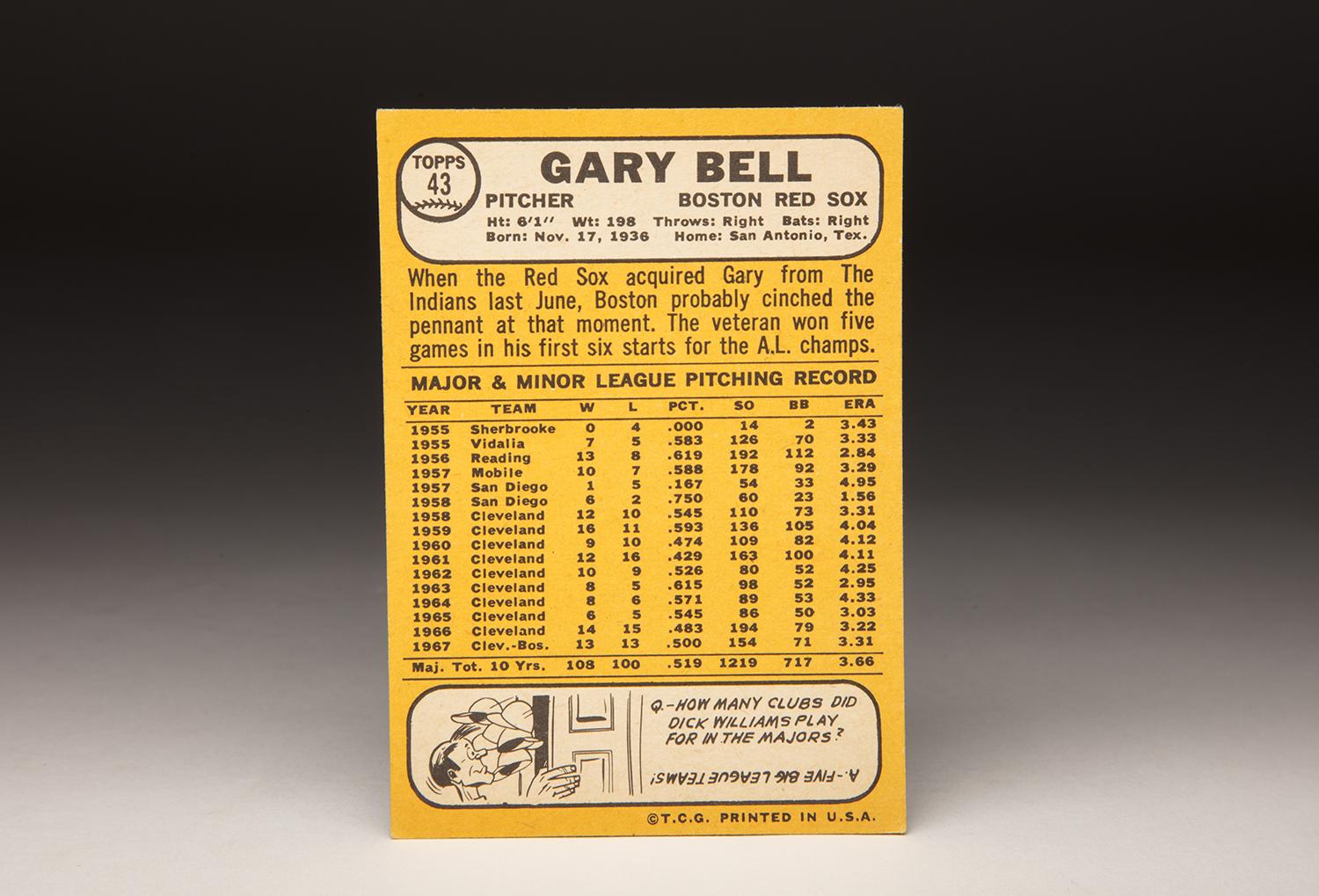

To make room for Bell on the roster, the Indians released veteran starter Mike Garcia, who was hurt and unable to pitch. Debuting as a reliever in the summer of ‘58, Bell moved quickly into the Indians’ rotation. Relying mostly on a power fastball, he made 23 starts, completed 10 of them, and put up a 12-10 record with a 3.31 ERA for the season. Bell’s numbers helped him finish third in the American League Rookie of the Year balloting.

In 1959, Bell again split his season between the rotation and the bullpen. Becoming a workhorse for manager Joe Gordon, the live-armed right-hander logged 234 innings, but struggled with his control, walking 105 batters against 136 strikeouts. With the strike zone becoming a bit of an obstacle, Bell saw his ERA rise slightly above 4.00. All in all, the season was a disappointment for Bell, who believed the Indians had the talent to win the pennant but had to settle for also-ran status behind the Chicago White Sox.

Over the next two seasons, Bell transitioned into fulltime starting. A strong start to the 1960 season resulted in his placement on the All-Star team, but a sore shoulder curtailed his performance in the second half and eventually resulted in the shortening of his season. Even when healthy, his control remained an issue, keeping his ERA above 4.00 and making him a sub-.500 pitcher.

In 1962, Bell took on a different role for the Indians and their new manager, Mel McGaha. (New managers were a constant theme for Bell. In his 10 seasons with the Indians, he played for nine different skippers.) Moving into the bullpen, Bell became the Indians’ relief ace. He saved 12 games, a good total for the era, but his ERA rose to 4.26.

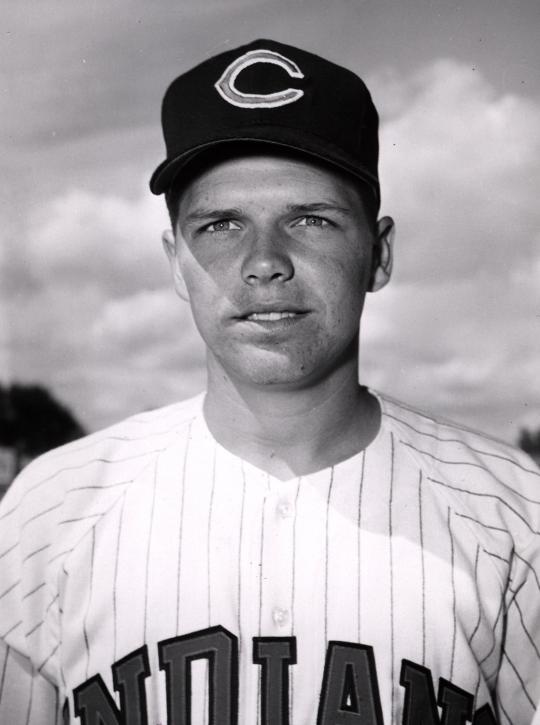

Bell would remain a reliever for the next three seasons. In 1963, the Indians acquired sidewinding Ted Abernathy and made him their closer, freeing up Bell to pitch in a long relief role. Bell put up the most consistent stretch of pitching in his young career, lowering his ERA to 2.95 and allowing only 52 walks in 119 innings, a better rate than his earlier seasons.

Over the next two years, Bell alternated a bad season (1964) with a good one (1965). The latter season was marred by an incident with a teammate. Although the fun-loving and outgoing Bell was generally liked in the Cleveland clubhouse, he did lose his temper with roommate Jack Kralick. One day, the two pitchers began to argue about which TV channel they wanted to watch. The argument soon devolved into fisticuffs. Bell won the fight, breaking one of Kralick’s teeth and cutting his face, but leaving manager Birdie Tebbetts displeased with both pitchers.

Prior to the 1966 season, Bell expressed his own level of displeasure with his role on the Indians. “Don’t get me wrong. I’m not mad at anybody. I’m not trying to alibi either,” Bell told Russell Schneider of the Sporting News. “But I’m not happy in the bullpen. I know I can still start and I’d like to have the chance – if not with this team, then with another.”

An old-school manager like Tebbetts might have reacted with anger, but not in this case. Tebbetts decided to return Bell to the starting rotation. The results were fabulous. Putting up an ERA of 3.22, Bell won 14 games in 1966 and struck out 194 batters in 254 innings. He also made the All-Star team. Now 29 years old, Bell joined two younger starters, Sam McDowell and Steve Hargan, in forming one of the better rotations in the American League.

That turned out to be the last hurrah for Bell in an Indians uniform. In 1967, he started the season by losing five out of his first six decisions, which was partly the result of bad luck. On June 4, the Indians decided to use Bell in an effort to upgrade their offense; they dealt him to the Red Sox for two power hitters, first baseman Tony Horton and outfielder Don Demeter.

Some pitchers dreaded pitching at Fenway Park, but not Bell. He felt comfortable pitching in the old park, despite the short distances to left field. The Red Sox inserted Bell into the rotation and watched him win 12 out of 20 decisions while posting an ERA of 3.16. The Red Sox needed every one of those wins, as they held off three rivals for the American League pennant. In the World Series, Bell received a start in Game 3, and did not pitch well in losing to St. Louis. But in Game 6, manager Dick Williams called on him to close out the game, which he did with two shutout innings, allowing the Red Sox to force a seventh game.

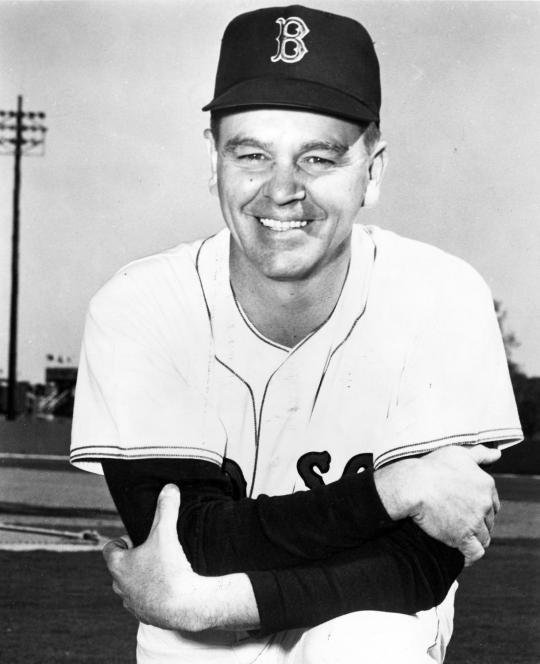

Bell’s first summer in Boston also brought about some attention to his famous head of hair. Shortly after the trade, Bell’s wife Nan told a Boston newspaper that she didn’t like that her husband had to wear a cap because it covered up his “beautiful hair.” Later in the interview, Nan added the following bit of information: “I go to the barber shop with Gary to make sure the barber doesn’t cut off too much hair.” Not surprisingly, the comments from Nan drew their share of laughs in the Bosox’ clubhouse, where his new teammates ribbed him mercilessly.

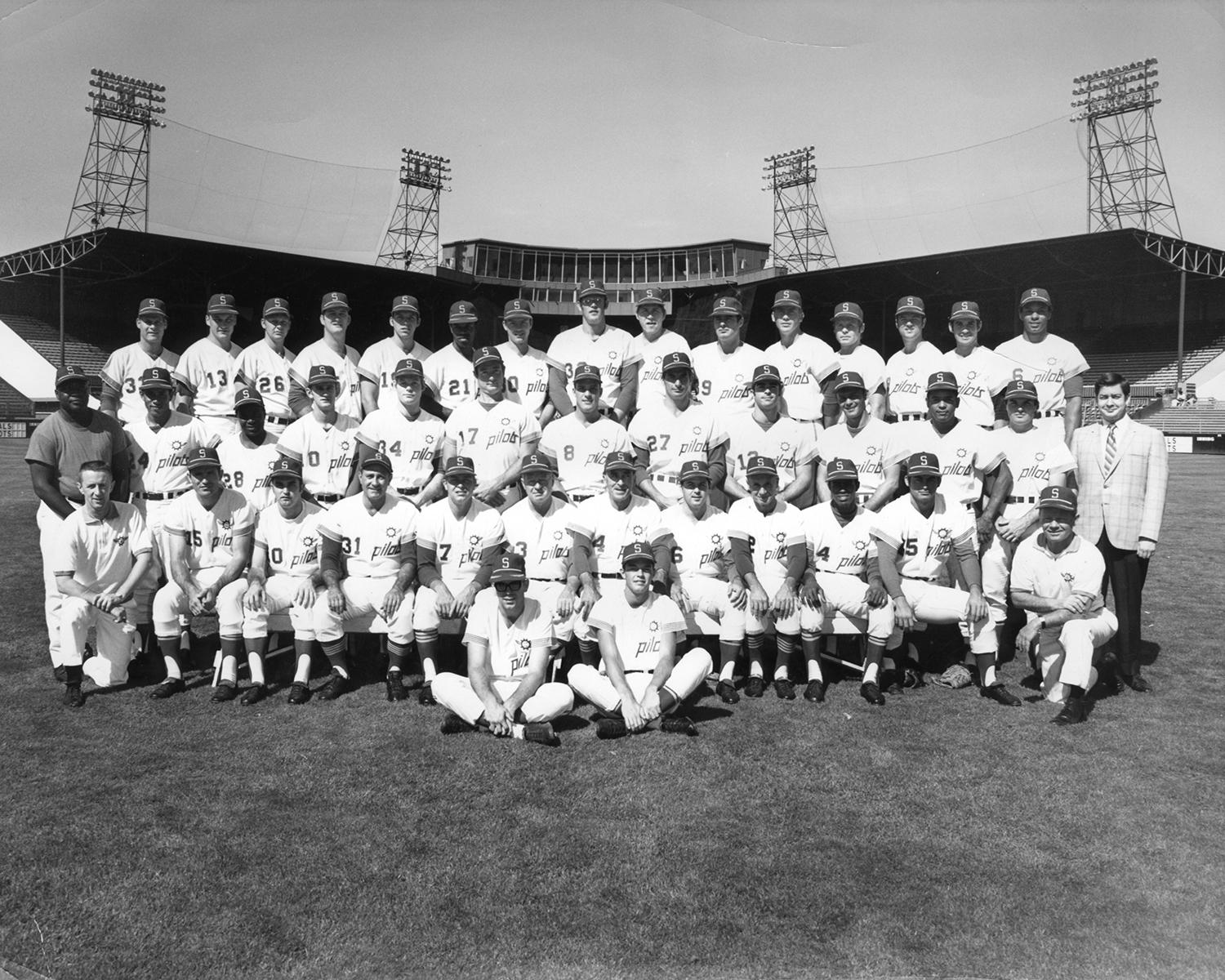

In 1968, Bell saw his workload cut by manager Dick Williams, but when he did pitch, he proved effective, splitting 22 decisions as a No. 3 starter behind Ray Culp and Dick Ellsworth. Though Bell had pitched well for the Red Sox, he was now on the wrong side of 30 – 31 to be exact. With the expansion draft coming, the Red Sox found themselves unable to protect Bell. The Seattle Pilots, viewing Bell as the potential anchor to their inaugural pitching staff of 1969, took him with the 21st pick of the expansion draft.

But after pitching a shutout on Opening Day, a game in which he somehow scattered nine hits and four walks, Bell fell into a major slump. In total, he made 11 starts with Seattle and was mostly ineffective. One week before the June 15 trading deadline, the Pilots traded the veteran starter, sending him to the Chicago White Sox for reliever Bob Locker.

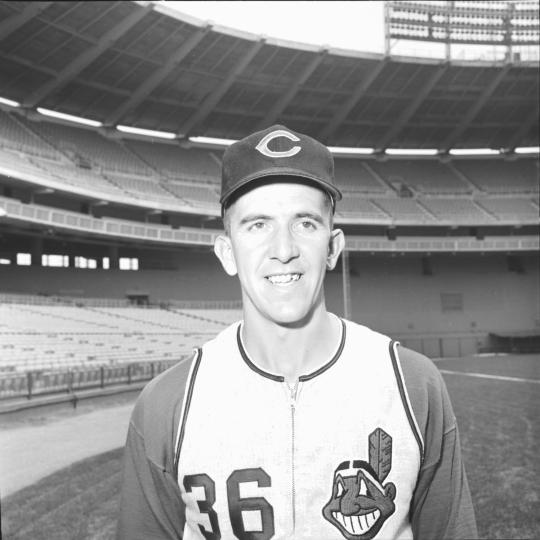

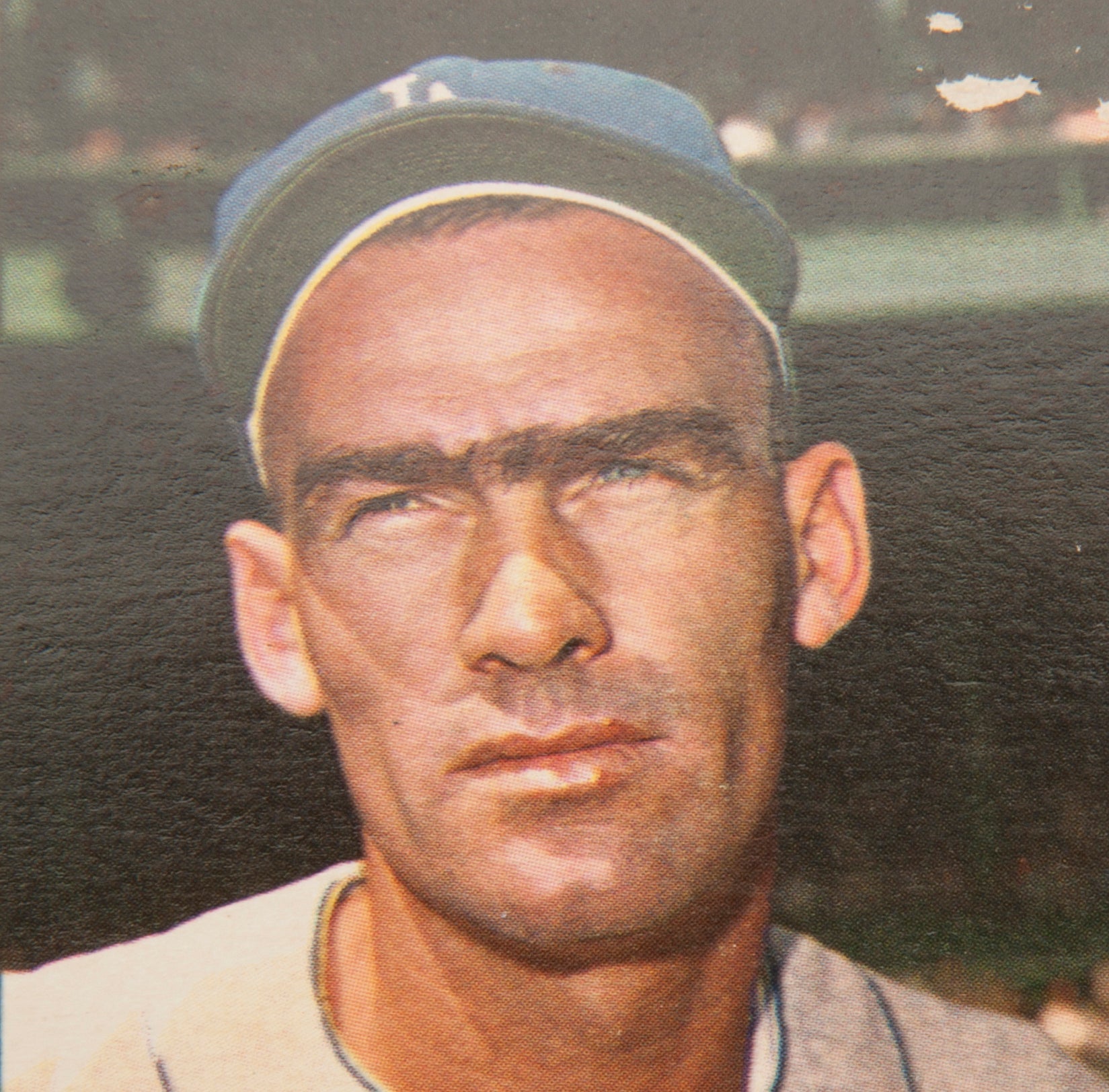

To make room for Gary Bell on the roster, the Cleveland Indians released veteran starter Mike Garcia (pictured above) in 1959, who was hurt and unable to pitch. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

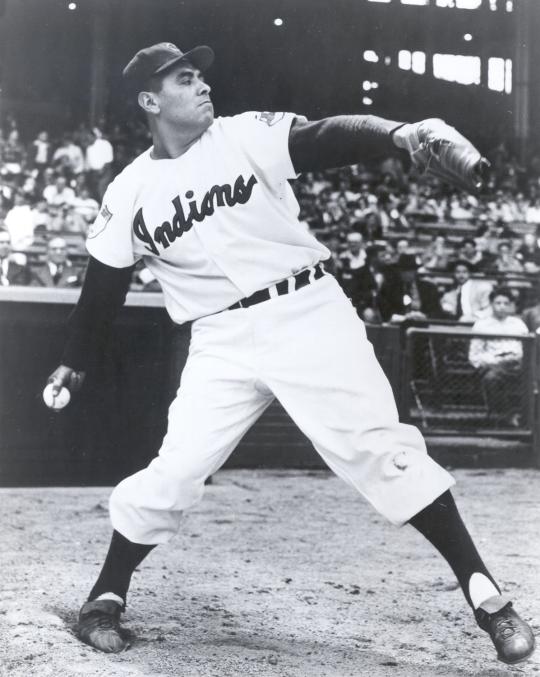

Gary Bell played for the Cleveland Indians from 1958-1967. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

In 1963, the Cleveland Indians acquired sidewinding Ted Abernathy (pictured above) and made him their closer, freeing up Gary Bell to pitch in a long relief role. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Bell’s tenure with the Pilots was not successful, but it would eventually make him a household name in baseball circles, in part because he was the roommate of Jim Bouton. A year later, Bouton’s Ball Four hit bookstores. The book, essentially a diary of Bouton’s season in Seattle, portrayed Bell as one of the more colorful and well-liked players on the Pilots. Within the pages of the book, Bouton revealed Bell’s nickname, which was relatively unknown, as “Ding Dong.” Created during his days in Cleveland, the nickname was an obvious play on his last name, but also made reference to his wisecracking sense of humor.

As Bouton wrote in Ball Four, when pitchers gathered to go over scouting reports on the Washington Senators, Bell kept offering the same advice for each hitter. “Smoke him inside.” Eddie Brinkman? Frank Howard? “Smoke him inside.” Bell’s teammates took his “scouting report” seriously, even though he was clearly delivering a repeated punch line. “Smoke him inside” became something of a rallying cry for the Pilots’ pitchers.

The trade to the White Sox brought about the final chapter of Bell’s major league career. After the trade, Bell struggled. With his fastball diminished and his curveball not quite good enough to overcome that shortcoming, he failed to win a game, posted an ERA above 6.00, and drew his release in October. Just like that, Bell’s days as a solid major league pitcher had come to an end.

Like many fading veterans of that era, Bell sought refuge with the Hawaii Islanders, a Triple-A team that afforded players the chance to spend a summer in Honolulu. As an added bonus, Hawaii was managed by Chuck Tanner, always the optimist among skippers. Bell enjoyed the weather and the atmosphere, but he simply couldn’t pitch anymore. An ERA of 8.31 in five games convinced him that it was time to retire.

Bell decided to leave baseball completely, first working in real estate before becoming a distributor of Miller Beer in the Phoenix area. From there, he transitioned to the sporting goods business and eventually purchased his own sporting goods company, which he ran successfully for more than 20 years. Bell has also been active in the MLB Players’ Alumni Association. One of the leaders of the group since its inception, the good-natured Bell often attends charitable golf tournaments and participates in free clinics for children.

Now retired and in his early 80s, Bell lives in San Antonio, Texas. Based upon available photographs, he still has that beautiful hair. It has turned mostly gray, but it remains thick, with no baldness in sight.

It’s good to know that some 50 years later, some things in baseball have not changed.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame