- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Bobby Tolan

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Bobby Tolan

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

As a famous philosopher once said, “You can observe a lot by watching.” That bit of wisdom, once espoused by Yogi Berra, applies to each baseball card.

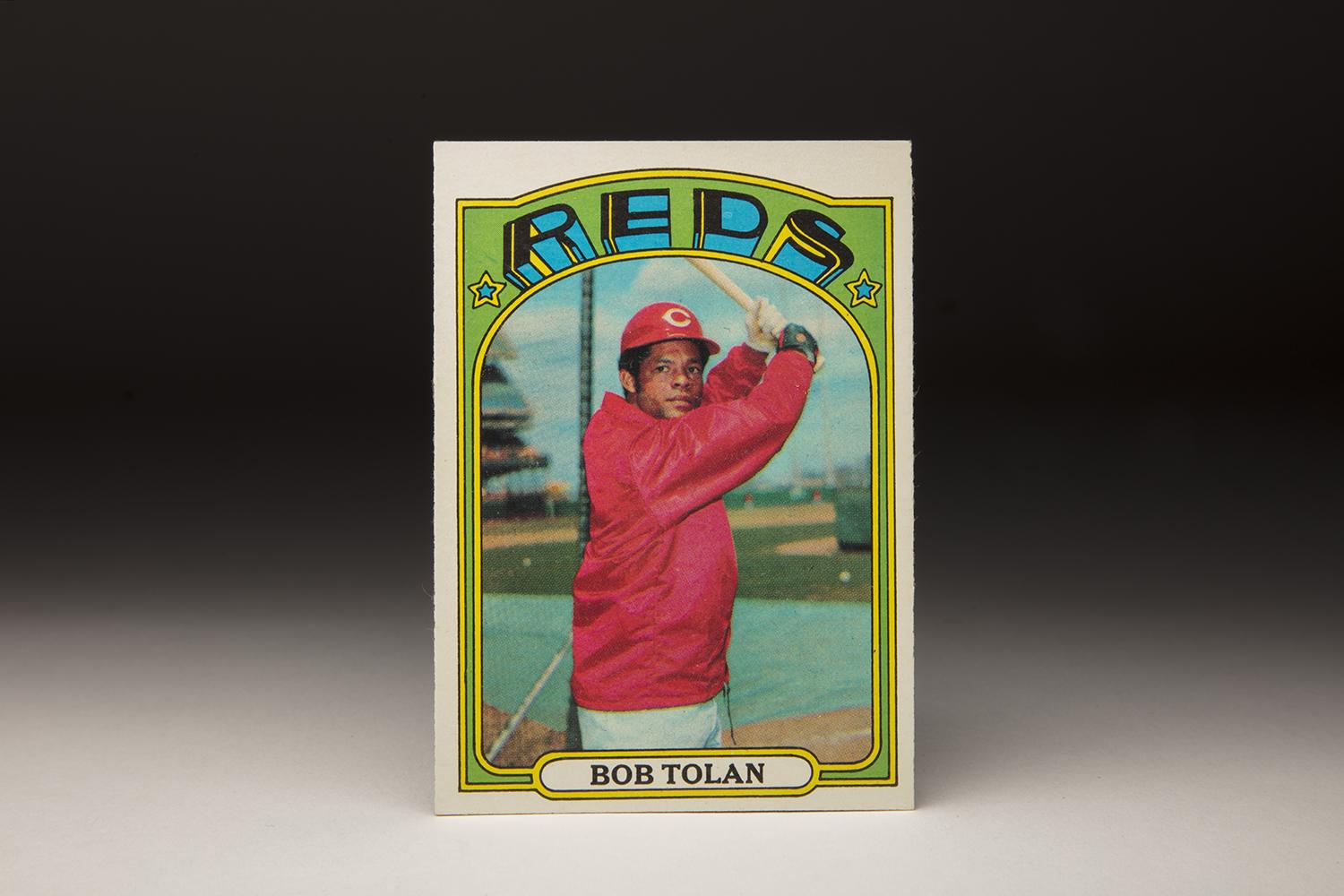

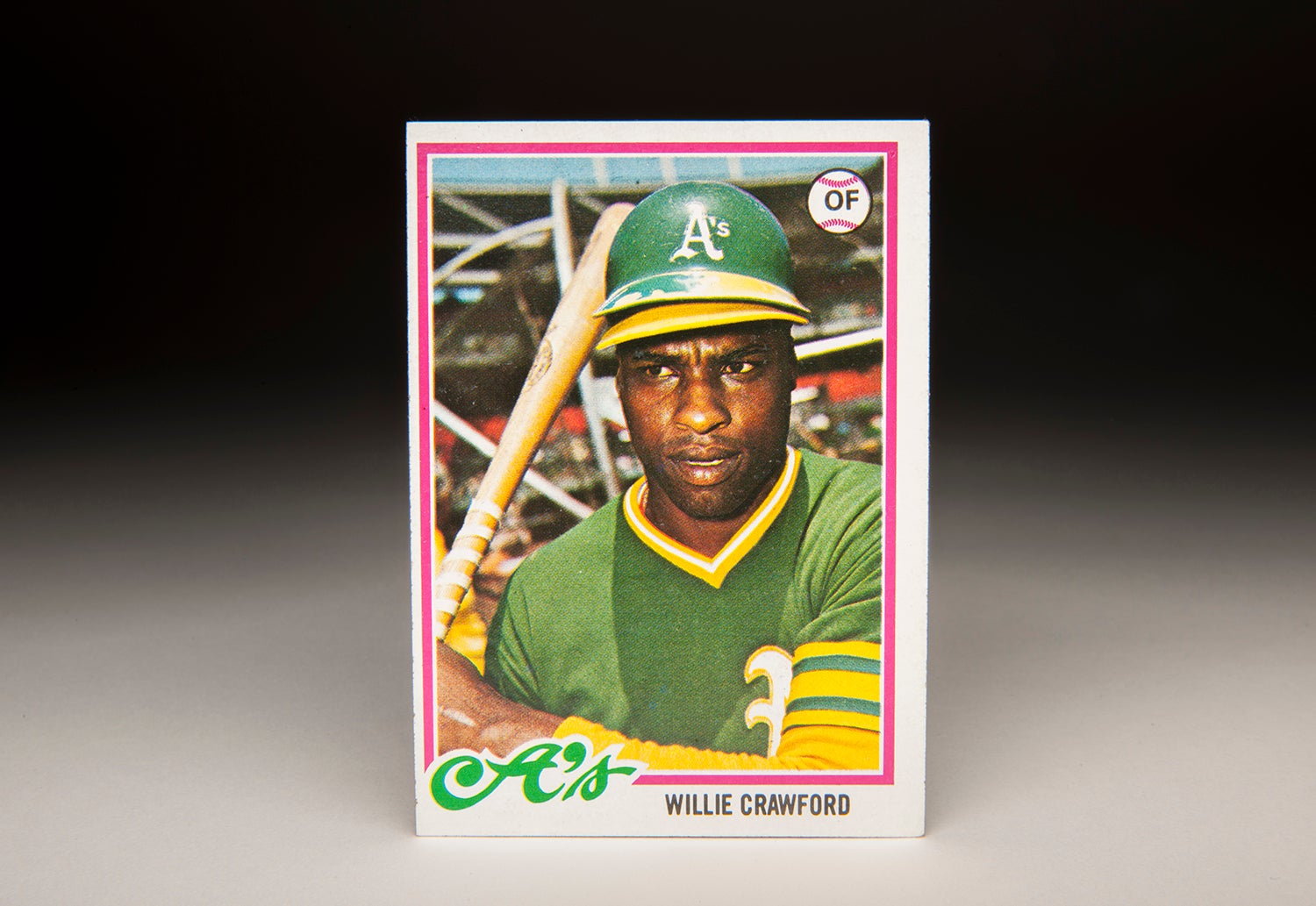

Some cards reveal more than others. One that falls into the more revealing category is Bobby Tolan’s 1972 Topps card. Oh, where to begin with this wonderful piece of cardboard?

Tolan’s windbreaker is probably the most obvious starting point. By the early 1970s, windbreakers had become the fashion choice of players during both Spring Training and the cooler days that sometimes infiltrate the regular season in April and May. Back in the 1920s and ’30s, players wore wool sweaters as a way of keeping warm. By the 1940s, the sweaters had given way to jackets made of leather. Then came the windbreakers, which became so popular that players used to wear them underneath their jerseys during spring training. Players did that as a way of trying to sweat off some extra pounds that had been added during the long winter. It’s a look that appears weird to us today, but back in the early 1970s, it was one of the cool things to do for a ballplayer.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

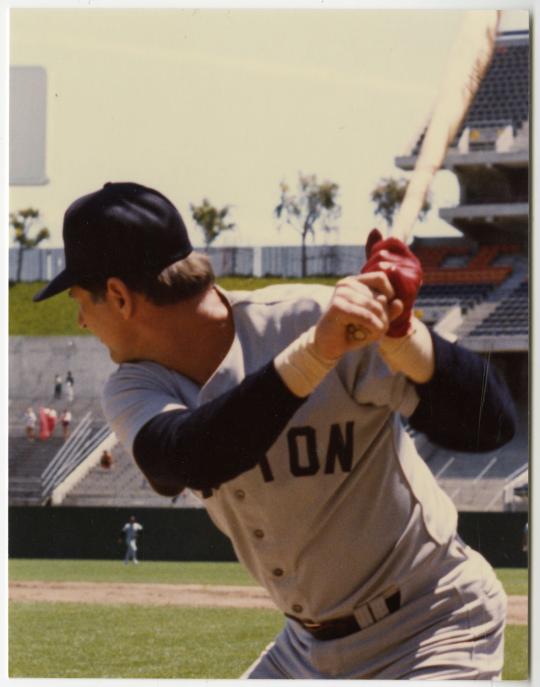

In Tolan’s case, we see him wearing the windbreaker outside of his jersey, in a conventional manner. Given its length and its bright red color, the windbreaker dominates the layout of the photograph. It takes on even more prominence because of Tolan’s distinctive batting pose. Tolan liked to hold his hands high, raising his bat well above his head, just like Hall of Famer Carl Yastrzemski used to do in the 1960s and ’70s, and in the way that Craig Counsell (now the manager of the Brewers) did in more recent years. It makes you wonder how a hitter can possibly move his bat from such a high starting point into the strike zone quickly enough, but it worked for all three of these players, including Tolan.

Then there is the background of the photograph. As with many National League photos of the 1970s, this shot was taken at Shea Stadium, home of the New York Mets. So we know this is a regular season photograph, and not one taken during Spring Training. Even though the sky appears clear, Shea Stadium has a tarpaulin on the infield, an indication that rain might have been in the forecast.

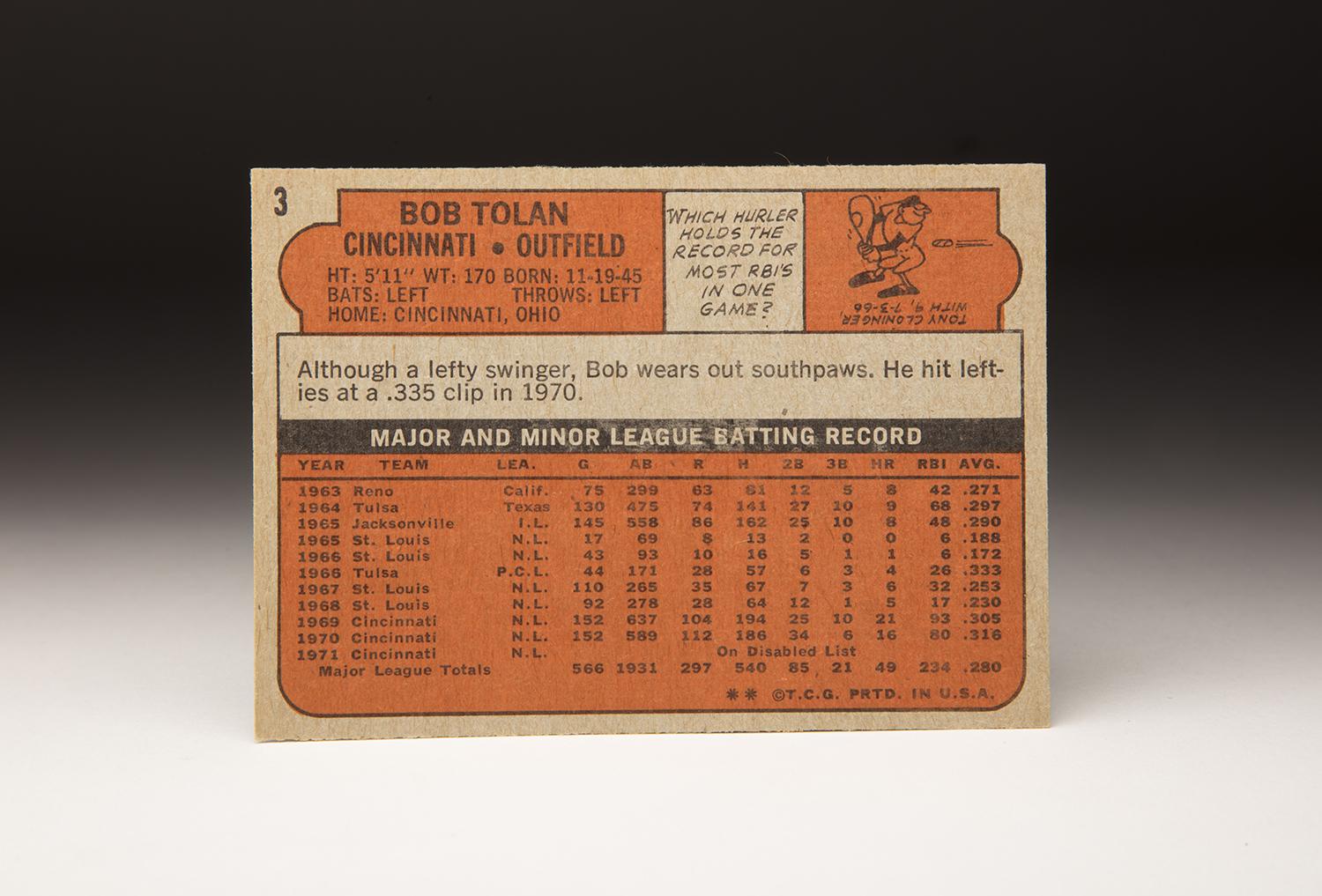

One other noteworthy item stands out about Tolan’s card. Topps lists him as “Bob” Tolan, and not “Bobby.” In looking at other Tolan cards from his career, Topps always identified him as Bob, even though very few people referred to him in such a way. I always remembered him as Bobby, beginning with the 1972 World Series, when I first heard his name, and continuing until the end of his playing career. Just like it was always Bobby Bonds or Bobby Murcer, it was always Bobby Tolan, but not on his baseball cards. Odd.

Lost amidst all of these observations is the fact that Tolan was a very fine player during the prime of his career. In 1963, the Pittsburgh Pirates signed Tolan as a first baseman. By this time, the Pirates’ organization, headed up general manager Joe Browne, had earned a reputation for an aggressive pursuit of young African-American talent, and Tolan fit right in. With his speed and long, lean body, Tolan became an appealing talent for the Pirates, but he lasted only one year in their minor league system. Under a rule at the time, the Pirates had to keep Tolan on their roster for the entire 1963 season, or risk losing him after a season. But the Pirates knew that the 17-year-old Tolan was not ready. After the season, the St. Louis Cardinals drafted him in the now extinct first-year player draft. Just like that, the Pirates had lost a prime prospect.

Like the Pirates of that era, the Cardinals believed in pursuing available African-American and Latino talent. They also felt that Tolan was miscast as a first baseman. So they moved him to the outfield, where he adapted quickly. Tolan put up huge minor league numbers in both 1964 and ’65, earning himself a call-up to St. Louis at the tail-end of the 1965 season. But Tolan was not quite ready; he hit only .188 in September, indicating that he needed some Triple-A seasoning in 1966.

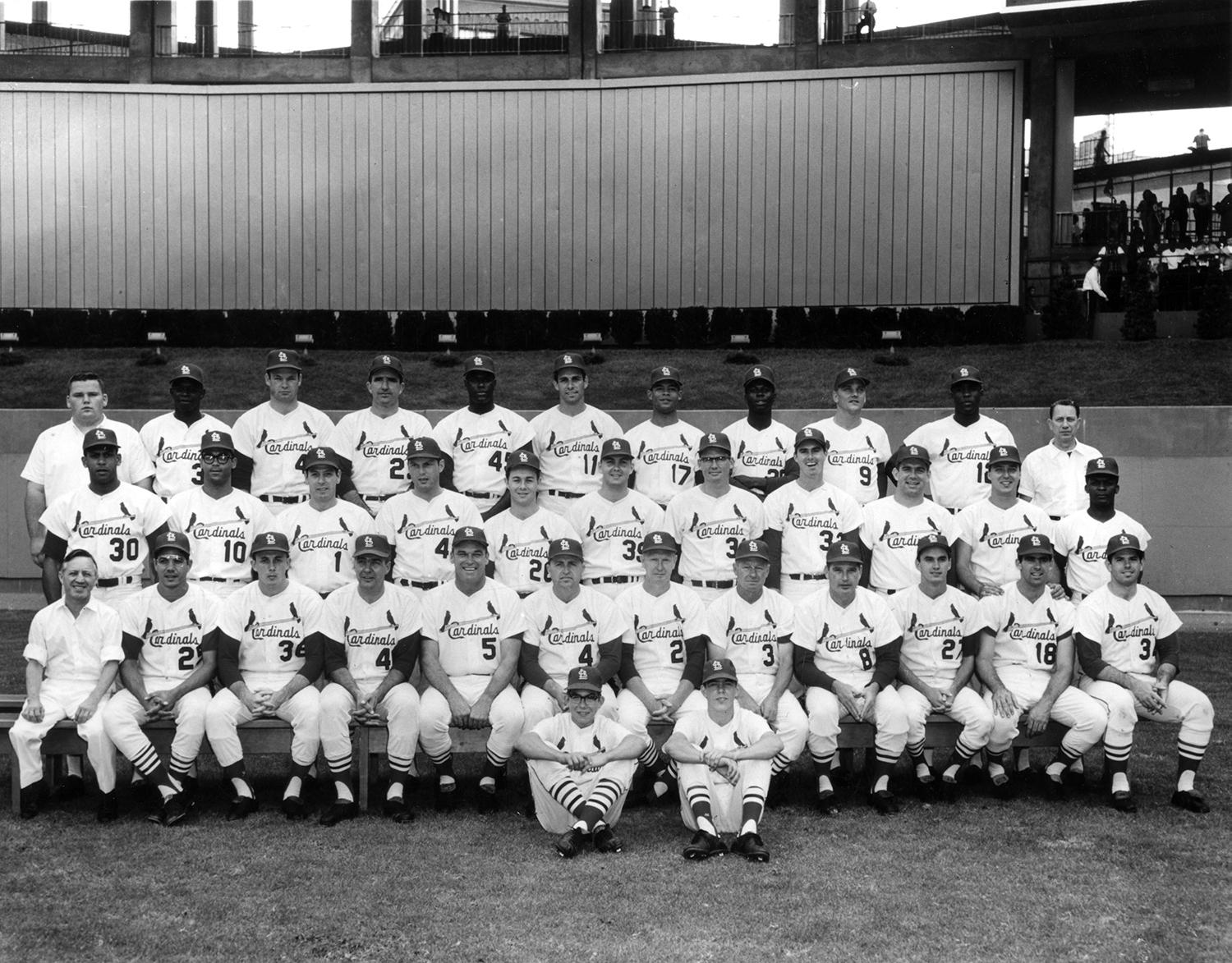

After a good start to the minor league season, the Cardinals rewarded Tolan with a fast call-up, but he again struggled, mandating another return to Triple-A. Finally, in 1967, Tolan began to gain a foothold. Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst turned to Tolan as his No. 4 outfielder, a versatile backup behind the formidable starting trio of Lou Brock, Curt Flood and Roger Maris. Tolan spelled both Flood and Maris, while occasionally giving Orlando Cepeda a day off at first base. Tolan remained with the Cardinals throughout the season, giving him a chance to experience his first taste of the World Series that fall. Tolan played sparingly in the Series, but still took home his first world championship ring after the Cardinals beat back the pesky Boston Red Sox in seven games.

Tolan’s speed, ability to hit line drives, and occasional power made him a promising player. If there was a weakness to his game, it was his lack of patience. In 1968, Tolan accumulated close to 300 plate appearances, but drew only 13 walks. His hitting suffered, as he remained overly aggressive at the plate. Still, he remained on the roster for the entire season and appeared in his second consecutive World Series, a seven-game loss to the Detroit Tigers.

By now, the Cardinals had hoped that Tolan would have earned a starting spot in their aging outfield. Maris had decided to retire while Flood was starting to show his age. But Tolan’s inconsistent hitting and poor rate of success on stolen base attempts hurt him. Wondering whether Tolan would ever mature as a ballplayer, the Cardinals decided to move on. Only a few days after the 1968 World Series, the Cards opted for veteran experience in the outfield, sending Tolan and sidearming reliever Wayne Granger to the Cincinnati Reds for aging star Vada Pinson, a player whom Tolan admired and also a player with whom Tolan had been compared.

The change of scenery turned out to be elixir for Tolan, who gave much of the credit to his new manager, Dave Bristol. “In Spring Training in ’69, Bristol told me, ‘Don’t worry about anything. You’re one of our starting outfielders. You’re not going to be platooned or pinch-hit for,’ ” Tolan told the Cincinnati Enquirer in recalling the words of his manager. Sure enough, Bristol moved Tolan into the starting lineup, using him in both of the outfield corners. Bristol batted him second, right behind leadoff man Pete Rose and just ahead of another young talent, fellow outfielder Alex Johnson. Tolan found a comfort zone batting second. Posting an OPS of .821, Tolan hit 21 home runs, stole 26 bases and added a level of dynamism tom the Reds. He still swung at too many pitches, drawing only 27 walks over a full season, but he was coming closer to tapping his enormous all-round potential.

Patience would come to Tolan’s game in 1970. He drew 62 walks, more than doubling his output from 1969. Now on base more frequently, he stole 57 bases. He also batted .316. Those numbers garnered him some support in the National League MVP balloting. The Reds won the National League West Division, sending them to the postseason, where Tolan continued his standout play. In the second game of the NLCS, he blasted a home run. Then in Game 3, he drove home the winning run. In the World Series, he added a home run against Baltimore, one of the few Reds’ highlights during a five-game defeat.

Thrilled with Tolan’s development, the Reds believed that he would man center field for them for close to the next decade. But then came an ill-advised decision during the winter. Tolan opted to play in an exhibition basketball game with some of his Reds teammates, a violation of his contract. Tolan and the other players had been given verbal permission by Sparky Anderson, but the front office had previously informed the Reds’ players that they would have to disband their winter basketball team. Sure enough, Tolan injured himself on the court, completely tearing his Achilles tendon. It was a devastating injury, one that had ended or curtailed the careers of other players. For a player like Tolan, who relied on his speed, the injury was especially harmful. He reinjured the Achilles in the spring, forcing him to miss all of the 1971 season and putting his career into further doubt.

The Reds were not happy. Their hardnosed, old school general manager, Bob Howsam, had little sympathy for Tolan. Howsam believed that Tolan had foolishly violated his contract, hurting his team badly in the process. Without Tolan, the Reds tried Hal McRae in center field, but he was better suited to playing left field. They shifted the newly acquired George Foster to center field, but that proved to be a bad fit, too. They also tried backups like Buddy Bradford and Ty Cline, but they were not everyday players. When the Reds finished fourth in the National League West, well out of contention, the front office placed most of the blame at the feet of Tolan.

Upset with himself, Tolan worked hard to recover from the Achilles tear. He dove full bore into the rehabilitation, strengthening his heel and his legs. Some skeptics believed that Tolan would never play again, but he proved them wrong, readying himself for Opening Day in 1972.

The start of the season was delayed by a player strike, giving Tolan extra time to make his return. Not only did he play on Opening Day, but he appeared in 142 games that season, a remarkable workload for a player coming back from an Achilles injury. Regaining much of the speed that might have been lost because of the tendon tear, Tolan stole 42 bases, batted .288, and piled up 88 RBIs, all numbers that exceeded Reds expectations. Tolan earn the Comeback Player of the Year Award and also the prestigious the Hutch Award, named for the late Reds manager, Fred Hutchinson, and given to the player who exemplifies an unusual level of spirit in overcoming adversity.

As a bonus, Tolan played in his fourth World Series that fall. Tolan stole five bases against the Oakland A’s, but also misplayed two balls in Game 7, which the Reds lost by one run. Still, Tolan’s remarkable comeback remained one of the highlights to Cincinnati’s season.

The summer and fall of 1972 would represent Tolan’s final triumph in a Reds uniform. The 1973 season turn into a disaster. Tolan saw his batting average sink into the low .200s, the worst offensive season of his career. The Reds also moved him out of center field, where they made room for the defensively gifted Cesar Geronimo, and placed Tolan in right field. Tolan’s attitude also suffered. He battled Reds management, which continued to hold a grudge for the way in which he had blown out his Achilles tendon.

While Tolan’s Achilles was causing him no trouble now, his back had begun to act up. At one point, the Reds’ director of player personnel, Sheldon “Chief” Bender,” ordered Tolan to report for an early morning appointment with a doctor. When Tolan complained to Bender about the inconvenience of the early appointment, a shouting match ensued in the clubhouse. To make matters worse, Tolan skipped out on the appointment.

In response, the Reds fined Tolan $300 for missing the appointment, insubordination and using abusive language. They also tried to place him on the disabled list, but National League president Chub Feeney ruled that Tolan was not sufficiently injured. Tolan remained on the active roster, but still found himself on the bench, having lost his position in right field to a young Ken Griffey. Tolan responded by filing a grievance against the Reds through the Players’ Association. To this day, Tolan has claimed that he was legitimately hurt, but says the Reds forced him to remain in the lineup with a bad back.

In August, Tolan left the team for two days without permission. When he returned from his unexplained absence, he was sporting the beginnings of a beard. That represented a violation of the Reds’ strict policy against facial hair of any kind. Reds skipper Sparky Anderson reminded Tolan of the team rules, and the outfielder responded by shaving the beard.

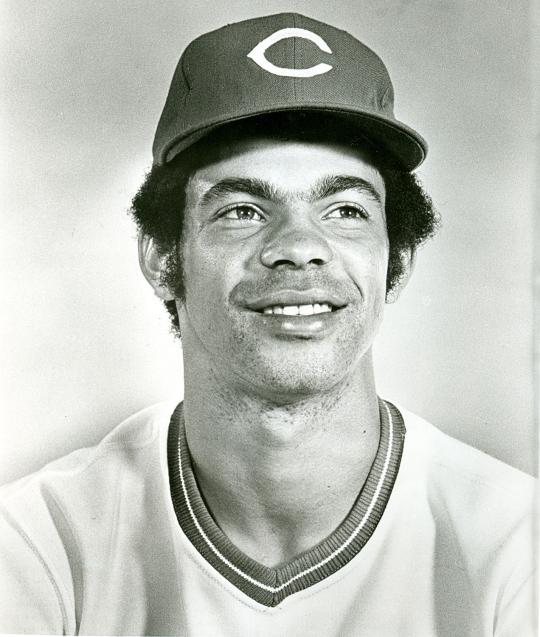

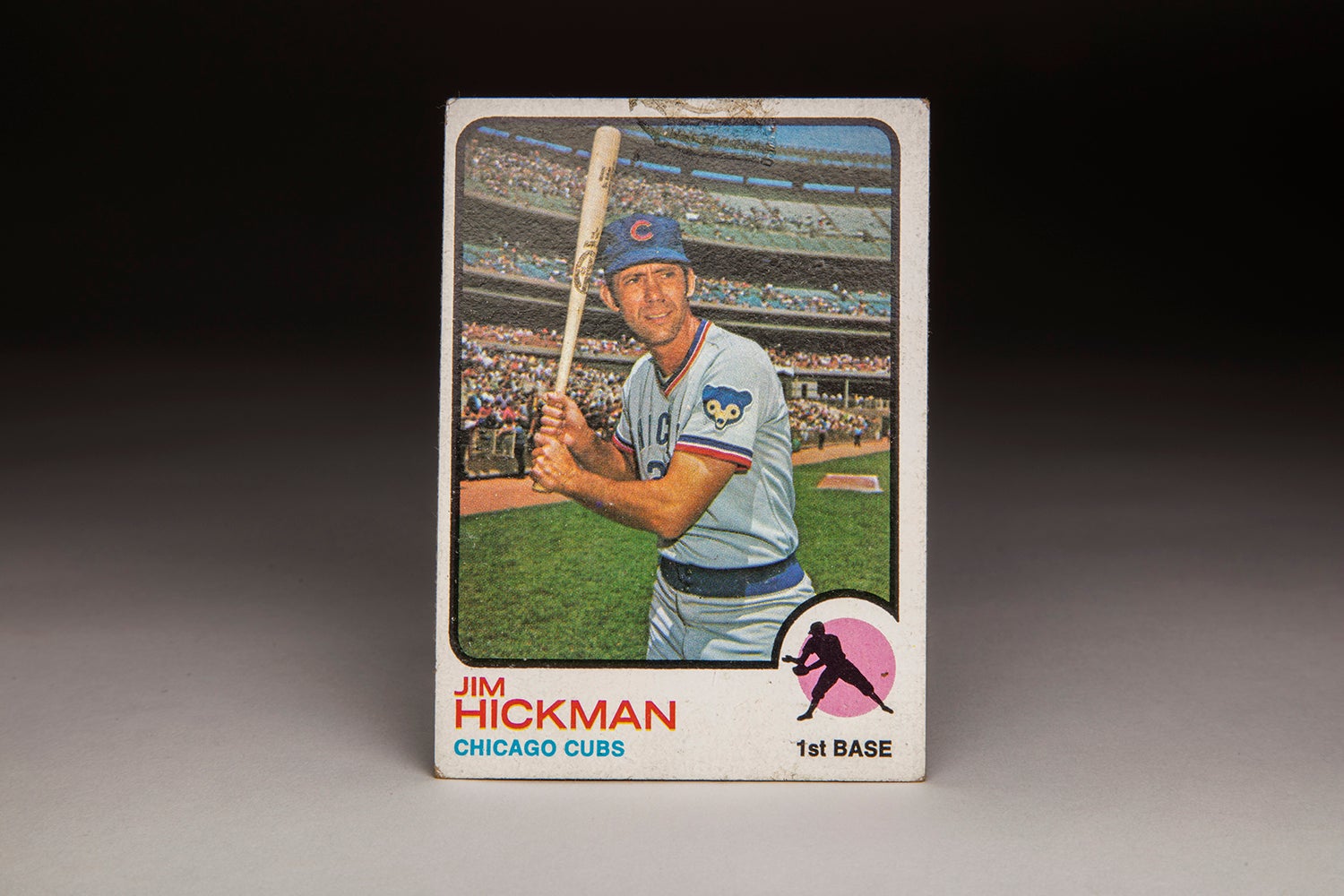

Bobby Tolan liked to hold his hands high, raising his bat well above his head, just like Hall of Famer Carl Yastrzemski (pictured above) used to do in the 1960s and ’70s. (Doug McWilliams/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

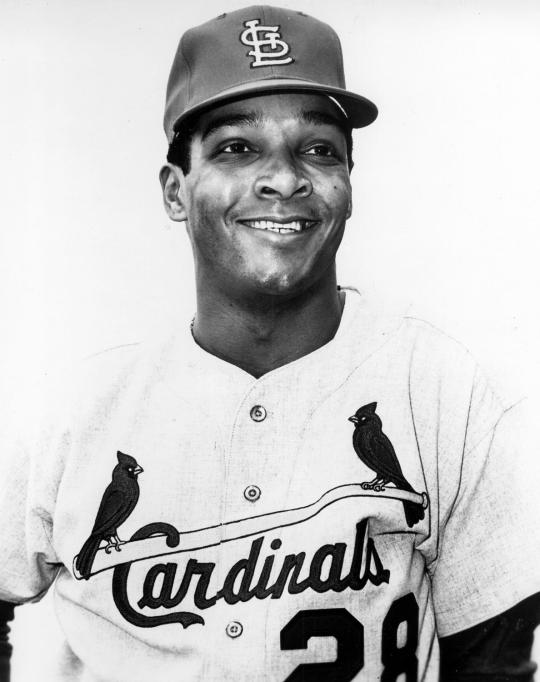

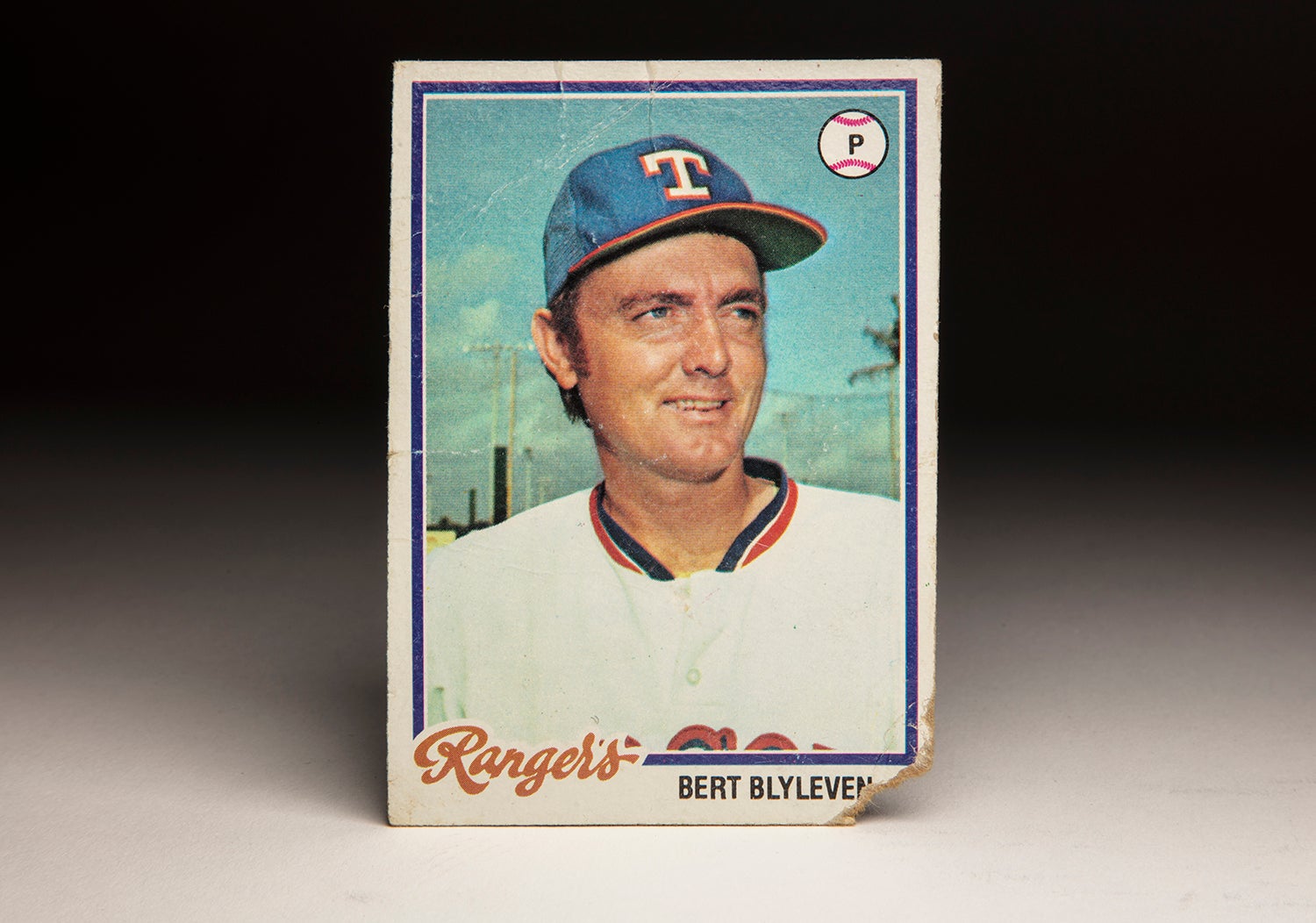

A few days after the 1968 World Series, the Cardinals traded Bobby Tolan to the Cincinnati Reds with sidearming reliever Wayne Granger for Vada Pinson (pictured above), a player with whom Tolan had been compared. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Then came another development. Tolan began to refuse taking part in either batting or fielding practice. Having already alienated team management, Tolan made himself an outcast among his teammates. By late September, the Reds had seen enough; Reds management suspended him for the balance of the 1973 season, including the Championship Series against the New York Mets.

The situation came to an inevitable conclusion that winter. The Reds parted ways with Tolan, dealing him to the San Diego Padres for right-hander Clay Kirby. After making his debut for the Padres in 1974, Tolan learned that he had won his grievance against the Reds. An arbitrator told the Reds they would have to repay him the money that they had fined him. Apparently not satisfied, Tolan demanded that the Reds publicly apologize for slandering him, but Cincinnati management refused to do so.

At his peak, Tolan had been a star with the Reds, but he played at an average level with the Padres. He made a few headlines in 1974, when he refused to sign his contract. Tolan and the head of the players’ union, Marvin Miller, believed that if he left the contract unsigned, he would then nullify the reserve clause and be allowed to become a free agent at season’s end. But ultimately, the Padres offered Tolan a two-year deal, which he agreed to sign. Tolan then dropped his grievance over the reserve clause.

Tolan played one more season in San Diego before drawing his release. Facing the unemployment line, Tolan accepted an offer from the Philadelphia Phillies.

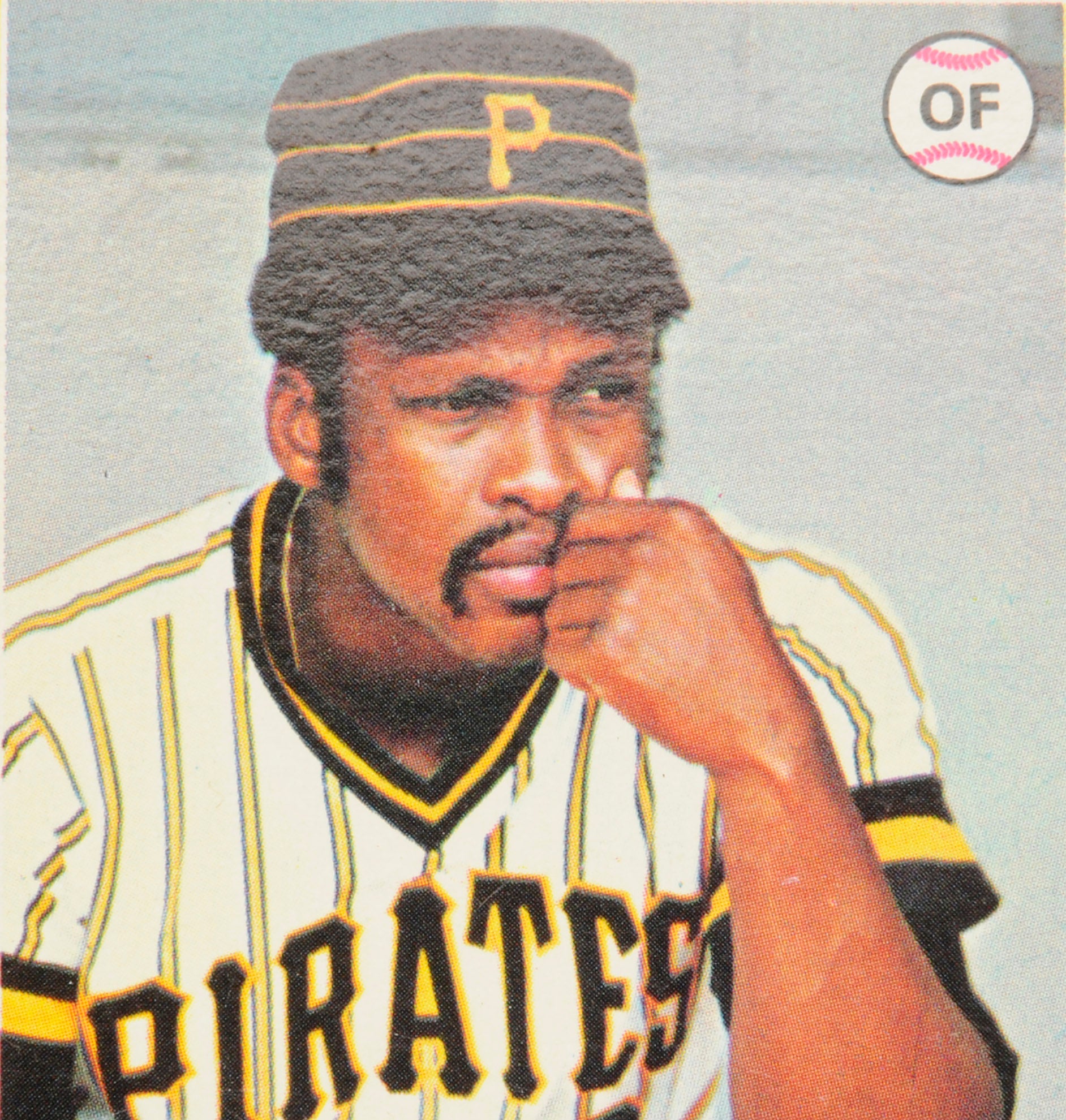

In 1976, Tolan played well as a backup outfielder for the Phillies, hitting .261 in a part-time role and moving on to the NLCS against his former team, the “Big Red Machine” of Cincinnati. Tolan hoped to be part of another Phillies playoff team in 1977, but he endured a terrible start to the season, resulting in his release. Tolan eventually signed with Pittsburgh, his original organization, but his hitting suffered. At season’s end, the Pirates allowed him to leave via free agency.

Once again, Tolan faced a critical stage in his career. When no major league teams showed interest, he decided to try his luck in the Japanese Leagues, signing with the Nankai Hawks. Like a lot of American players in the Far East, Tolan struggled to adapt to the culture. Unhappy in Japan, he moved on after one season. He then signed with the renegade Inter-American League, a new minor league venture featuring dozens of former major leaguers. Drowning in debt, the league folded after only three months, leaving Tolan out of work. Somewhat surprisingly, he received a call from the Padres, who liked Tolan, in part because he had been a positive influence on young teammates like Derrel Thomas. The Padres brought back Tolan as a reserve outfielder, where he played out the season before being released in October. At 33, Tolan’s career was over.

In 1980, the Padres hired Tolan as third base coach and batting instructor under their new manager, Jerry Coleman. During the 1981 strike, the Padres reassigned Tolan to work with young hitters at their Class A affiliate in Walla Walla, WA. In so doing, Tolan became the first hitting coach for a young prospect named Tony Gwynn. Later on, Tolan transitioned to minor league managing, worked briefly as a coach for Seattle (on the staff of Hall of Famer Dick Williams), and later returned to managing. Even though Tolan has long since left Organized Baseball, he still coaches a collegiate summer league team in Houston, where he won four titles in his first four seasons.

Unfortunately, controversy has continued to follow Tolan in his post-playing days, albeit in an indirect way. Back in 2008, his son Robbie, a minor league outfielder in Washington’s system, was shot in his own driveway by a police officer. The officer mistakenly believed that the younger Tolan was armed and had stolen a vehicle. The Tolans, believing that Robbie had been racially profiled, filed a civil law suit against the city of Bellaire, Texas. The two sides reached a $110,000 settlement, but the injuries sustained by Robbie, who endured a bullet wound to his liver, essentially ended his playing career.

Given the incident involving his son and his own controversies, Tolan’s life hasn’t been easy. But it was good to see him in Cooperstown two summers ago, when he was invited to the 2016 Induction Ceremony as one of the guests of the newly honored Ken Griffey, Jr. Tolan has long been a friend of the Griffey family and also a strong influence on the younger Griffey, who as a child used to spend time in the Reds’ clubhouse.

Even with all of the controversies, Bobby Tolan seems to have found a peaceful place in retirement. He admits that some of the controversies from his playing days were his fault, and retains no bitterness. He has succeeded in having a positive impact on at least two Hall of Famers, along with other players, too. And card collectors will have always have fun remembering his windbreaker and that weird batting stance on his 1972 Topps card.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame