- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Dave Marshall

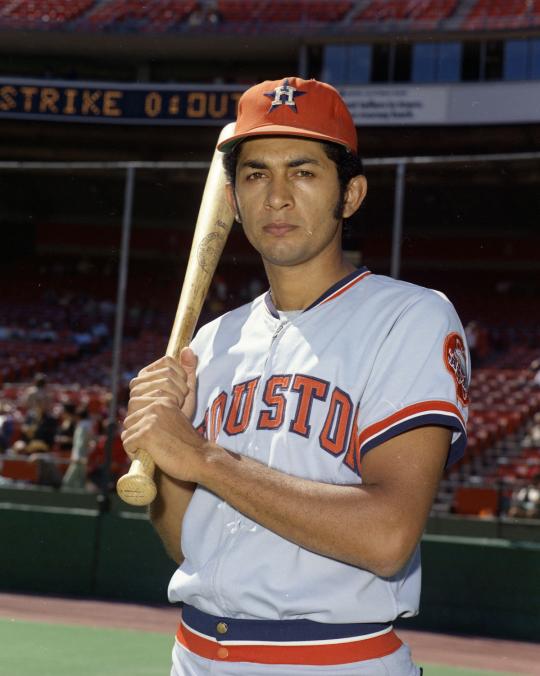

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Dave Marshall

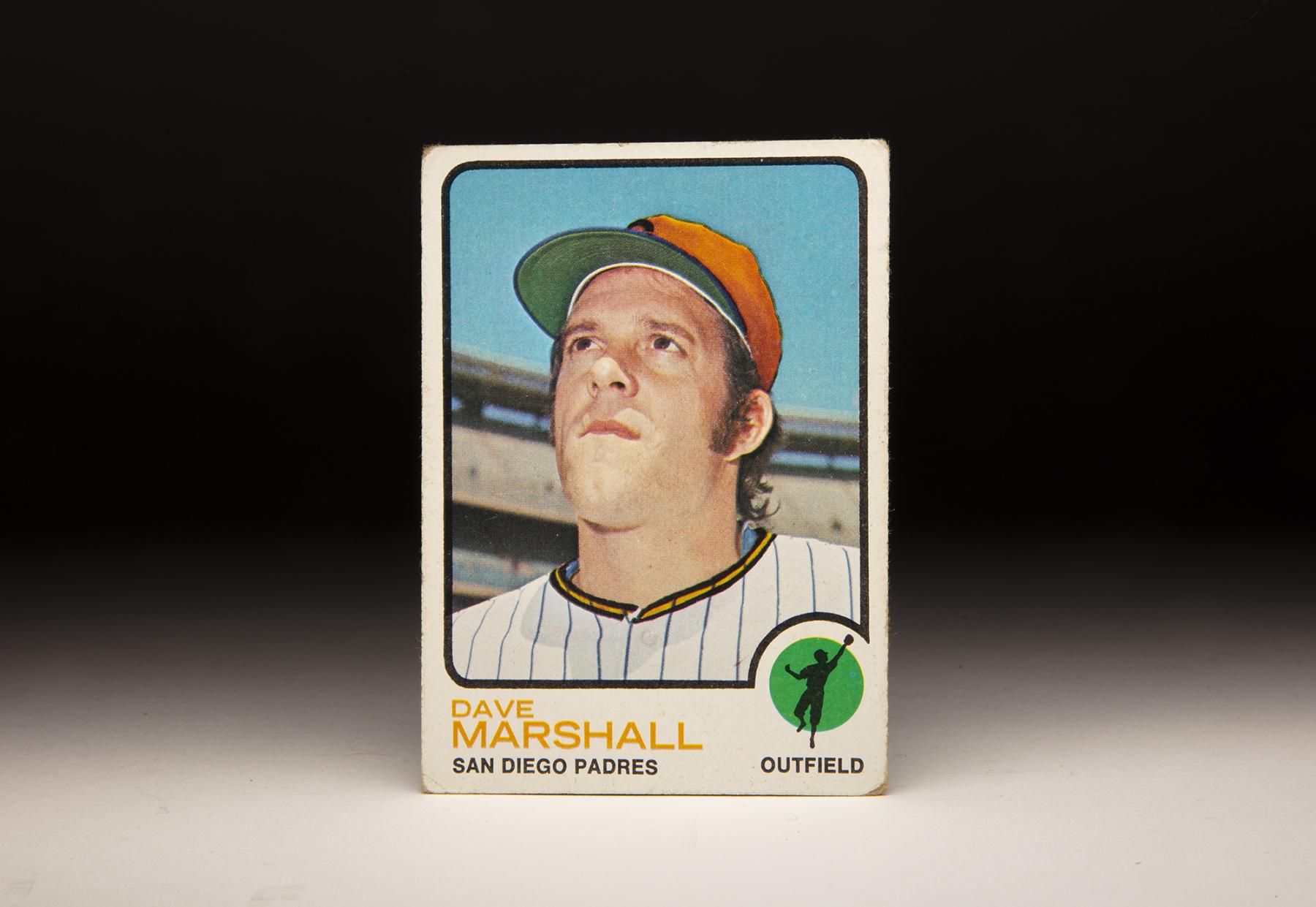

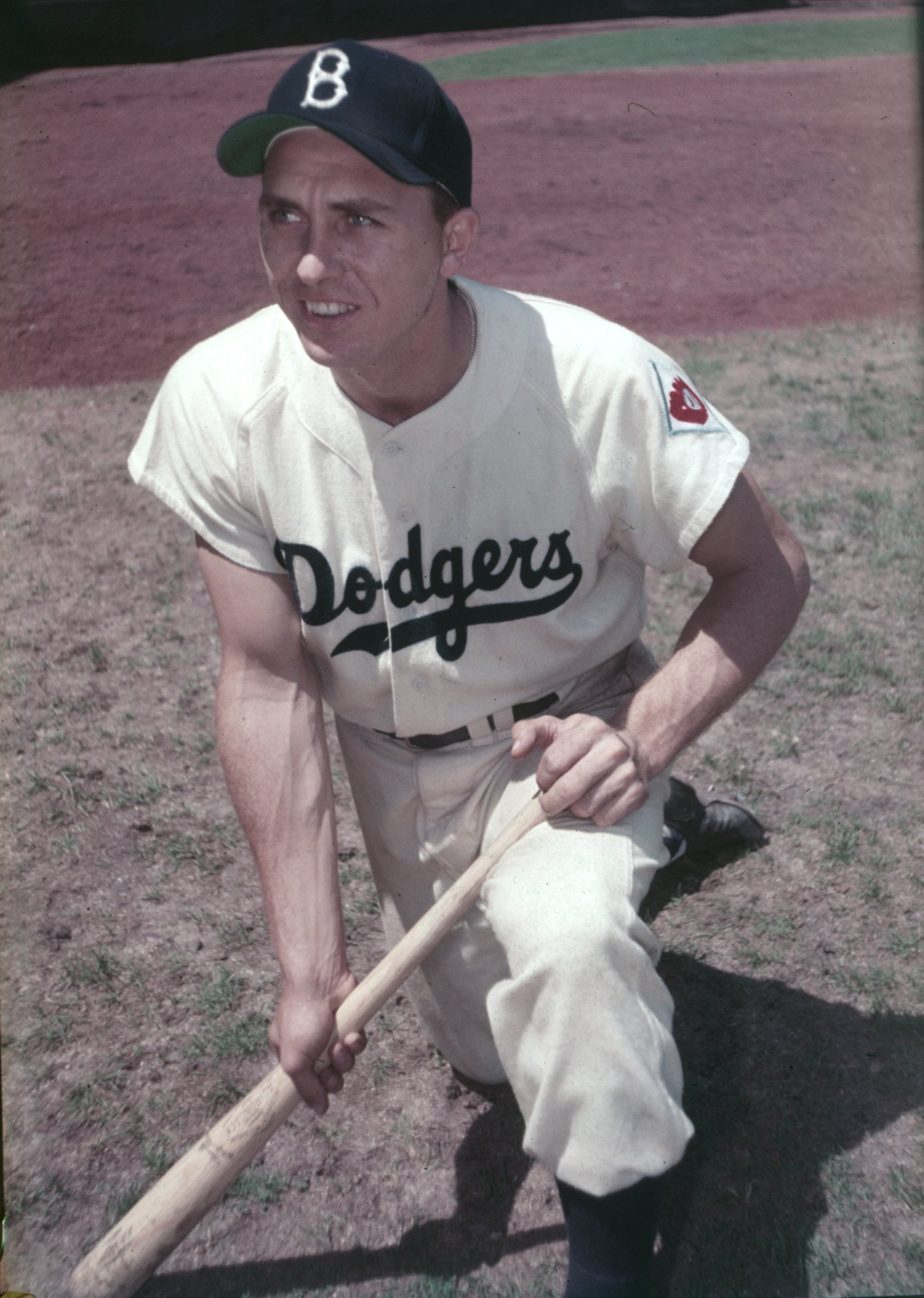

Dave Marshall’s 1973 Topps card speaks very much to the early 1970s. It’s a classic airbrush job from the time period, necessitated by the San Diego Padres’ acquisition of Marshall from the New York Mets during the preceding winter.

Topps has airbrushed the Padres’ yellow color onto his existing Mets cap, though in my mind, the yellow looks more like the gold used by the Pittsburgh Pirates at the same time.

Whether it’s gold or yellow, the cap doesn’t quite fit with the pinstripes on Marshall’s jersey. (While the blue stripes have been kept intact, notice that the thin collar has been changed from blue to gold, just like the cap.) Neither the Padres nor the Pirates used pinstripes at the time; those pinstripes were worn by the Mets during home games. And if that’s the case, then this photograph must have been taken at Shea Stadium, the Mets’ home, sometime during the 1972 season. The upper deck of Shea Stadium is apparent here, and given the emptiness of the stands, we can surmise that the photograph of Marshall was taken several hours before gametime.

Not only is the gaudy airbrushing of the card typical of Topps cards in the 1970s, but even the angle and the pose look familiar. The Topps photographer has taken the picture from near ground level, so as to give us the classic look of the upturned cap. Topps did this as a way of obscuring the cap logo, for the very purpose of dealing with players who moved from one team or another during the offseason. But in this case, the photographer allowed too much of the Mets’ logo and cap color to be seen, requiring that the work of the airbrush artist had to be added to the formula.

With these photographs, players are often seen with their eyes shifted upward and to the right; that must have been a directive from the photographers, who felt that the shifted eyes created a nice effect for the player’s pose.

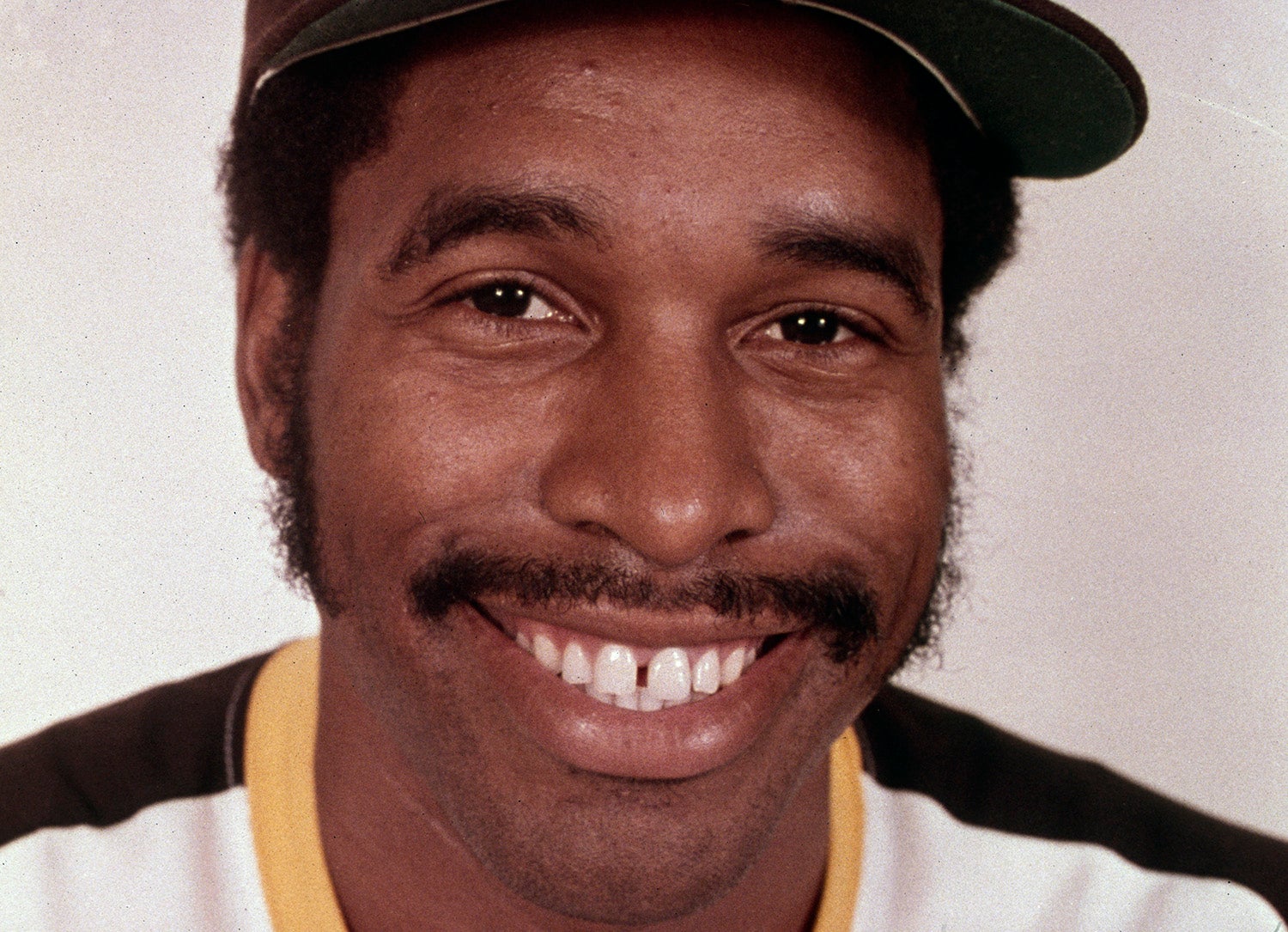

While the airbrushing and the angle of the photograph occupy much of our attention, let’s not forget that the card gives us a good look at Marshall’s face. With his strong chin and full face, Marshall had a rugged look that typified many players of the era. He also sprouted fairly significant sideburns around his left ear (and presumably the right ear, too), a fashion trend that many major leaguers had started to adopt circa 1972.

All things considered, I like the card, which was the last one put out by Topps for the journeyman outfielder. But you might be wondering, why a card for Dave Marshall? He was never a star, not even a household name and might even be a player you had never heard of before reading this article. Well, his Topps card came to my attention in June, when I heard that Marshall had passed away.

When players from the 1960s, 70s, 80s and 90s pass on, I have a habit of looking at their old cards. I guess it’s a ritual of sorts, one that helps me recall the cards of my youth, but one that also helps me pay a personal tribute to those players who have left us. And in the case of Marshall, the circumstances surrounding his death were particularly poignant.

Marshall’s story, at least his days as a ballplayer, began in 1963, when he signed with the Los Angeles Angels organization. The Angels assigned the young outfielder to Class A ball, where he struggled with both San Jose of the California League and Quad Cities of the Midwest League. The following summer, Marshall reported to Tri-City of the Northwest League; he played better there, hitting .261 with nine home runs in just over 100 games. Late in the season, the Angels decided to bump him all the way up to the Pacific Coast League, but he batted only .176 in 17 games for Hawaii.

In 1965, Marshall received a setback when the Angels sent him back to Class A to play for San Jose of the California League. Marshall showed off a disciplined batting eye, drawing 72 walks, but his .260 batting average and eight home runs left the Angels wanting more.

Marshall returned to the Angels for Spring Training in 1966, but he wouldn’t last into the regular season with the organization. In early April, the Angels made a trade, sending Marshall to the Giants for shortstop Hector Torres. The Giants immediately assigned Marshall to Waterbury of the Double-A Eastern League. He batted .287 with 64 walks, but also hit with a decided lack of power (only two home runs).

While his season was nothing outstanding, the Giants felt that Marshall could benefit from a stint in the Fall Instructional League, where he played exceptionally well. On the strength of his fall performance, Marshall earned a promotion to Triple-A Phoenix at the start of the 1967 season. Marshall blossomed at Phoenix, compiling a .294 batting average and an OPS of .828. Both numbers represented the high water marks of his minor league career. Those numbers, coupled with his classic left-hand swing and his strong defensive skills, left the Giants duly impressed.

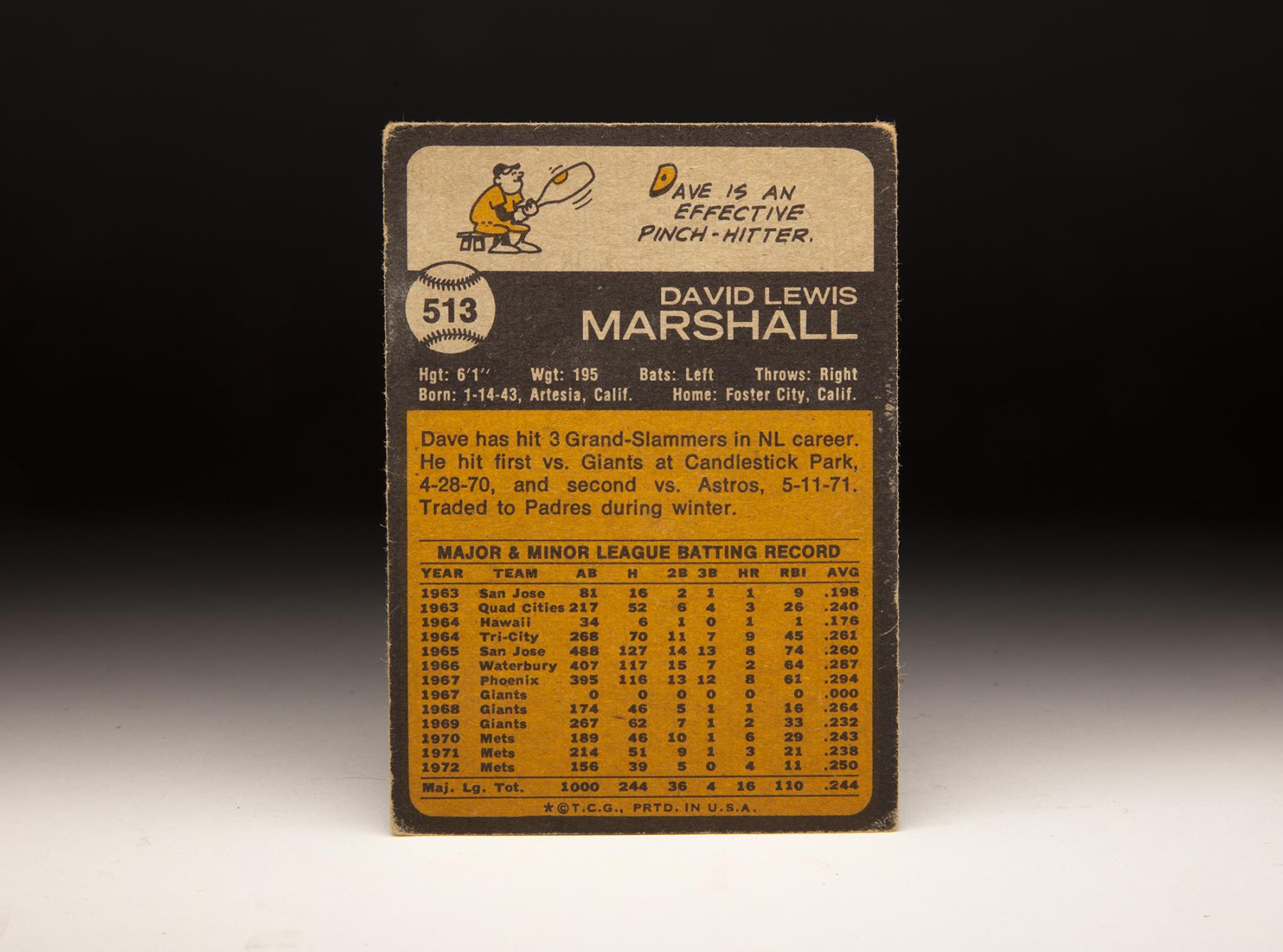

In early September, the Giants brought Marshall up to San Francisco. He appeared in just one game as a pinch-runner, but it was a hint at more major league service time to come his way in 1968.

In March of ’68, Marshall reported to Spring Training; for him it was the first time that he knew that he had an actual chance of making the major league team. Marshall played well that spring, securing a spot on the Giants’ Opening Day roster. That set him up for his biggest thrill as an athlete, coming on April 30 at Candlestick Park, when he started a game for the first time in his major league career.

“When I went out to right field,” Marshall told sportswriter Bob Stevens, “and looked over to my right, I suddenly thought, ‘It isn’t really happening, is it? I’m playing right next to Willie Mays!’ How does it feel? There must be 100 million kids who would give anything to be standing here where I am right now – next to Willie Mays.”

For much of the season, Marshall took on a role as a backup outfielder, playing behind the starting trio of Mays, left fielder Ty Cline and right fielder Jesus Alou. Marshall didn’t hit with much power (only one home run in 174 at-bats), but batted a decent .264 with a .338 on-base percentage. He also played very good defense in left and right field.

In 1969, the Giants made some changes to their outfield alignment. They moved top prospect Bobby Bonds into their starting lineup in right field, with Marshall sliding over to left field to replace Cline. Marshall received far more playing time that summer, appearing in 110 games, but failed to fully take advantage of the situation. While his fielding remained topnotch, he batted only .232 with two home runs.

The Giants also happened to be loaded with top outfield talent, including the switch-hitting Ken Henderson, a young George Foster and veteran Jim Ray Hart, whom the Giants had decided to transition from third base. With so many options, Giants general manager Chub Feeney felt that a trade was in order. That winter, he dealt Marshall and veteran lefty Ray Sadecki to the Mets for outfielder Jim Gosger and utility infielder Bob Heise.

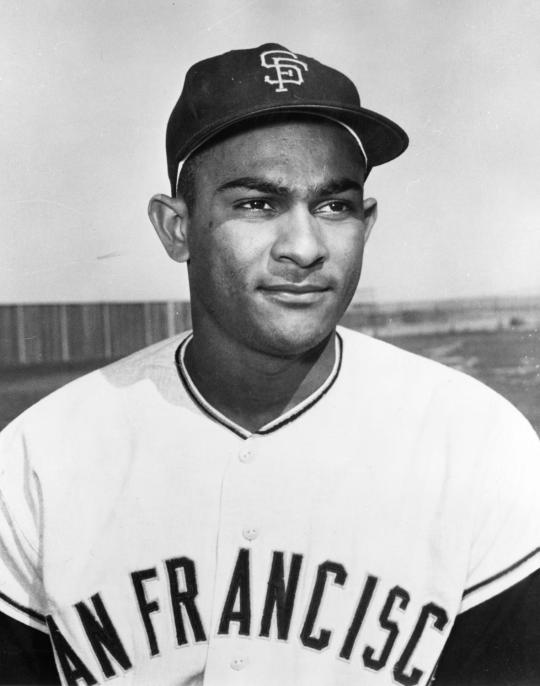

The defending World Champion Mets didn’t have as much outfield depth as the Giants, but they still had Cleon Jones in left, Tommie Agee in center and the platoon of Ron Swoboda and Art Shamsky in right field. That left Marshall to battle rookie Ken Singleton and veteran Rod Gaspar for the role of fifth outfielder. Marshall impressed the Mets during Spring Training, beating out Gaspar and Singleton for the final outfield spot on the Opening Day roster. As a reserve outfielder, Marshall hit better for the Mets than he had for the Giants, with six home runs and a .243 batting average.

In 1971, the Mets traded Swoboda to the Montreal Expos, but Singleton took most of the playing time in right field, with Marshall remaining in a reserve role. Appearing in an even 100 games, Marshall put up similar numbers to his 1970 production. He also became involved in a bit of controversy in September, but one that he did not initiate, when Swoboda criticized him for being satisfied as a backup and “wasting” his talent. Marshall did not hold back when asked to supply a response.

“Swoboda is wasting a lot of talent playing baseball,” Marshall told the Sporting News. “He should be in politics with all of those other windbags.”

In the spring of 1972, Marshall became involved in a milder controversy, this time when he reported to Mets camp 14 pounds overweight, drawing the ire of manager Gil Hodges. Initially, Hodges planned to fine Marshall $100 a pound for every pound he was overweight, but then chose not to levy the $1,400 punishment. Even after quickly dropping the excess poundage, Marshall saw his playing time take a downturn, mostly due to the additions of Rusty Staub and John Milner to the Mets’ outfield. Marshall played in only 72 games, but did post a respectable on-base percentage of .346.

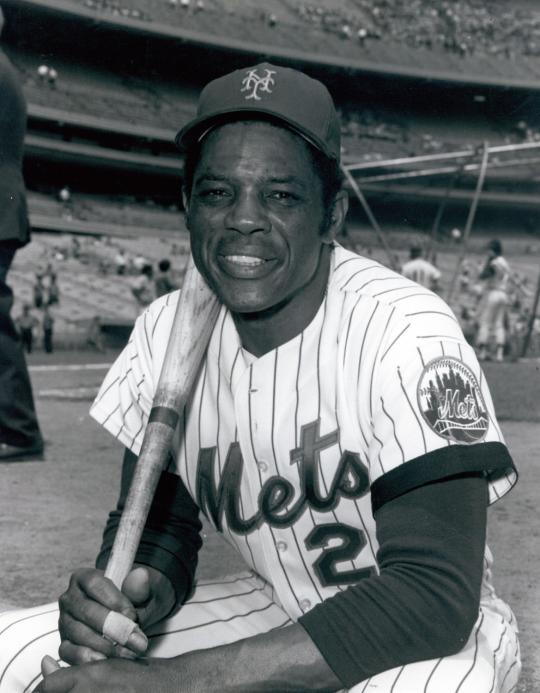

With the addition of Staub and the midseason acquisition of Mays from San Francisco, the Mets deemed Marshall expendable that winter. On Nov. 30, the Mets traded him to the Padres for reliever Al Severinsen. On the surface, more playing time seemed likely with lowly San Diego, but manager Don Zimmer gave most of the outfield playing time to Clarence Gaston, LeRon Lee and a young Dave Winfield. Marshall came to bat only 49 times, mostly as a pinch-hitter, but did post the best rate numbers of his career, including a .286 average and an OPS of .778. Unfortunately, an abundance of outfielders led to a midseason demotion to Triple-A Hawaii.

Marshall finished out the season at Triple-A, where he played poorly. In 40 games, he batted only .226 with little power. Discouraged by his minor league performance, the Padres sold him to the Chicago White Sox in late September. Marshall would never appear in a game for the White Sox, either in the major leagues or the minors. Instead he retired, his playing career ending at the age of 30.

Marshall chose not to remain in baseball, but found success elsewhere. Settling into life in California, he opened up a restaurant-bar, later becoming the owner of two others. He then worked security for a local hospital, before eventually becoming the chairman of Long Beach’s Parking and Traffic Management Organization, a position sometimes referred to as Long Beach’s “parking czar.”

Always friendly and willing to talk to people, even strangers, Marshall became known as the unofficial mayor of downtown Long Beach. He also found happiness away from the working world; in 1994, he married Carol, the love of his life.

Years later, Carol was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and her condition deteriorated so significantly that she had to be placed in a hospital. But she didn’t want that, and insisted on having hospice care at home, so that she could be near her husband. Dave himself had been struggling with health problems, including a congenital heart condition and a fractured skull that he had suffered in an accident involving a golf cart. Each of them rested in a hospital bed in their home, one right next to the other.

On June 4, 2019, Carol died. Only two days later, Dave passed away at the age of 76. One of his friends, a man named Charlie Beirne, told the Long Beach Press-Telegram: “I think he may have died from a broken heart.”

Technically, that is not a medical condition, but it is still very real.

Dave Marshall was not a particularly famous ballplayer, but his devotion to his wife was remarkable. Rest in peace, Mr. Marshall, along with your beloved Carol.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum