- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Matty Alou

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Matty Alou

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

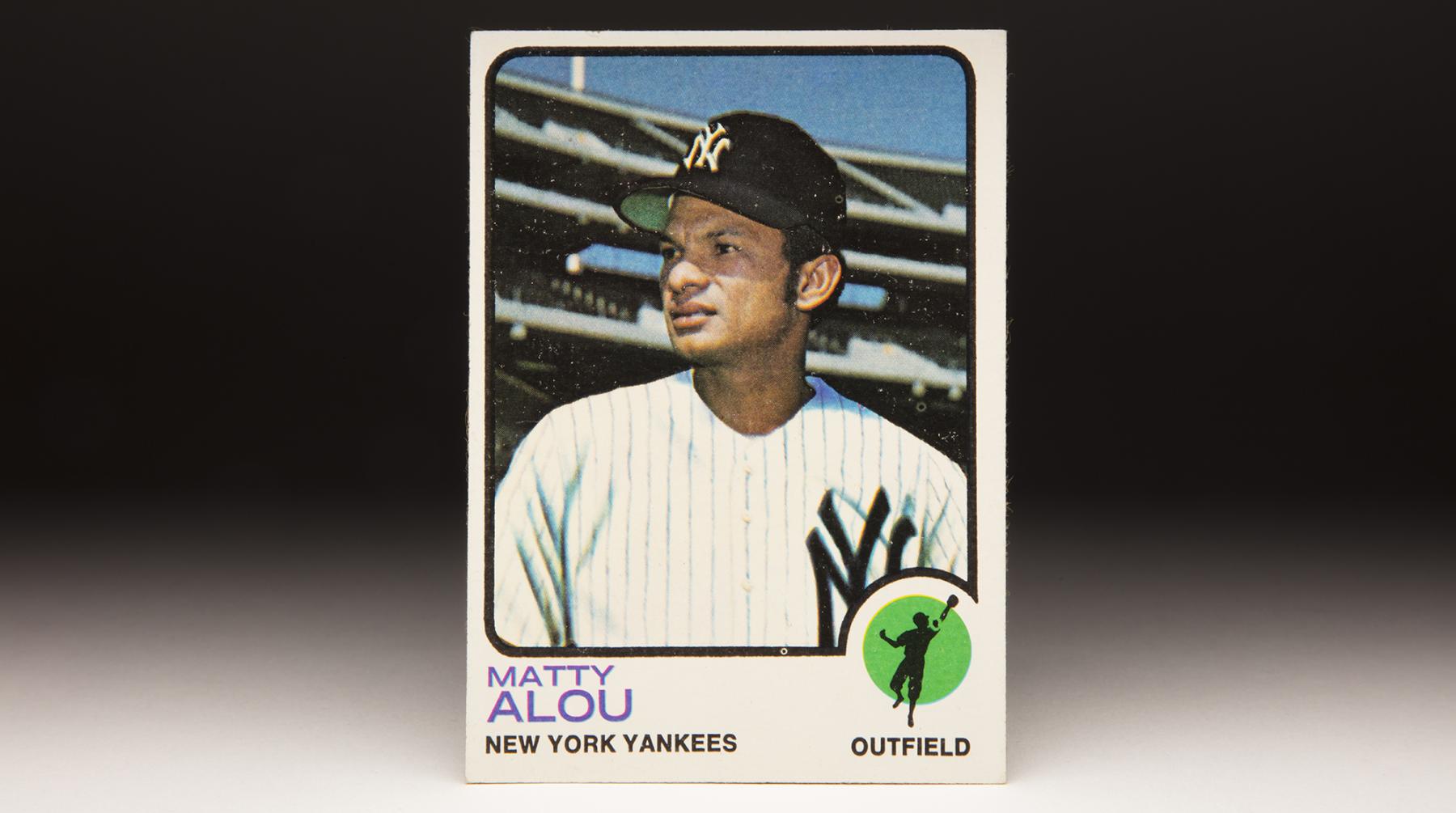

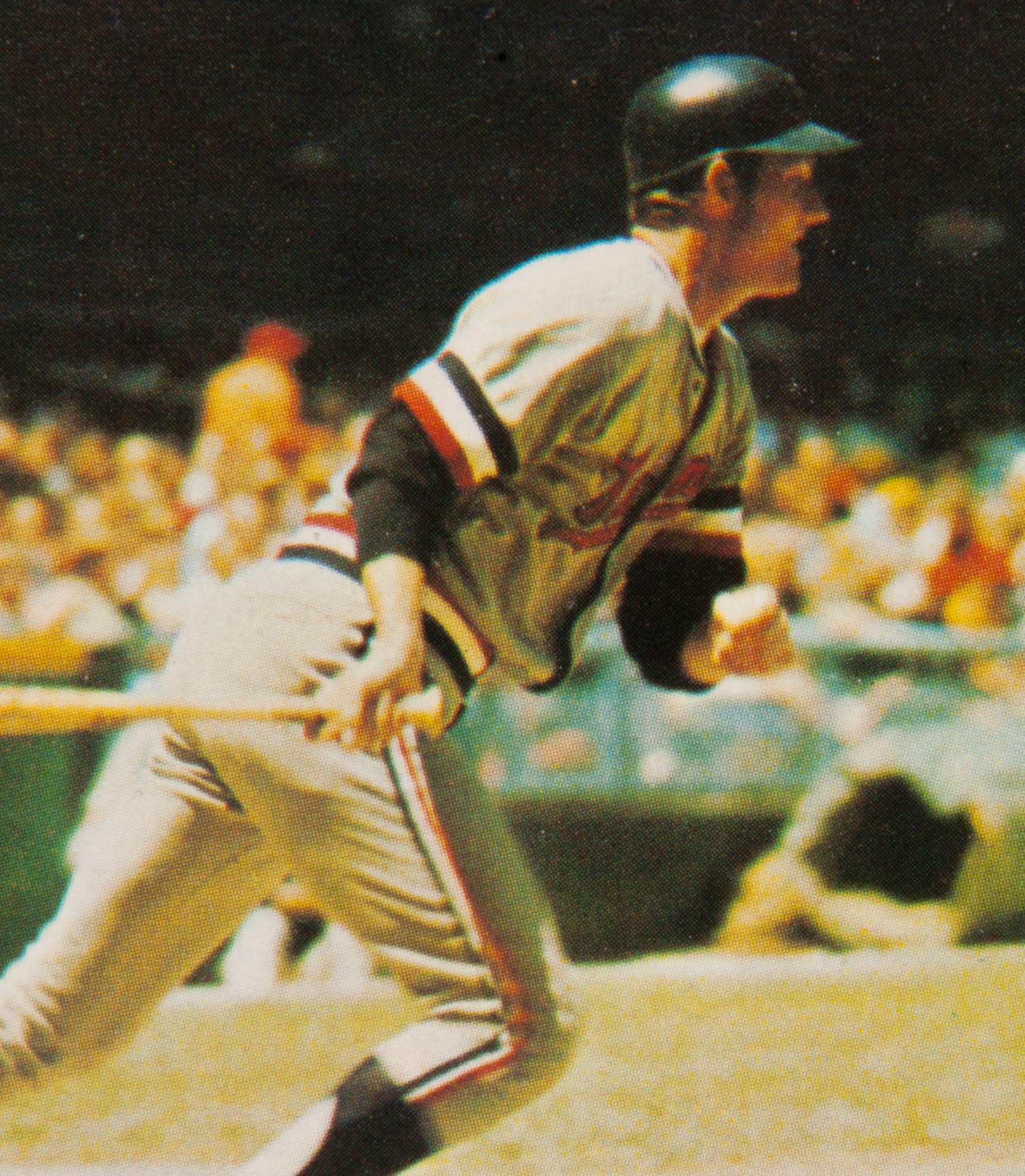

Something appears amiss with Matty Alou’s 1973 Topps card.

His home New York Yankees uniform does not fit the backdrop, which is not the old Yankee Stadium, but Oakland’s Alameda County Coliseum. Additionally, Alou’s Yankee cap looks a little too big for his head, and has a strange outline that appears out of place against the background of the stands.

And then there is that “NY” logo on the front of Alou’s jersey; it is way, way too large – far bigger than the actual logo that the Yankees used at the time.

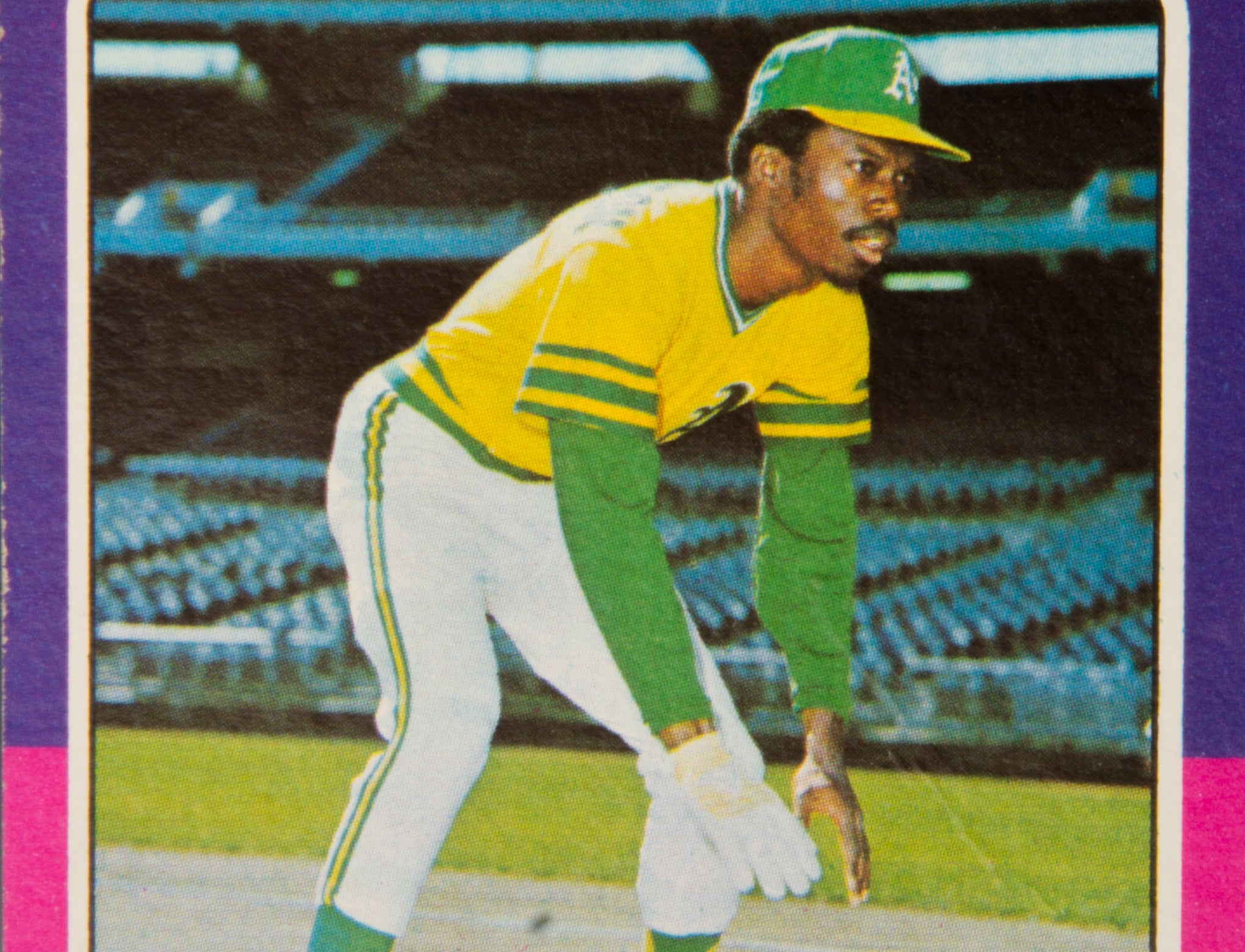

All of this, of course, is a product of Topps’ 1970s airbrushing methods. Alou did not play for the Yankees in 1972, when the photo was originally taken by standout photographer Doug McWilliams. At the time, Alou was playing for the Oakland A’s.

Late in the ’72 season, after the A’s acquired Alou and shortstop Dal Maxvill from the St. Louis Cardinals, Topps assigned McWilliams to report to Oakland Coliseum to procure updated photographs of both veterans for their 1973 set of cards.

McWilliams took several photos of Alou that day, including one that showed him posed with a bat in hand. All of the photos that McWilliams took for Topps showed Alou wearing Oakland’s green jersey and green-and-gold cap, and all of those colors became moot when the A’s decided to trade Alou to the Yankees after the 1972 World Series. In response, a Topps artist replaced Oakland green and gold with New York navy blue and pinstripes. So what started out as some typically good photographic work by McWilliams ended up being altered significantly by the art department at Topps.

Some collectors might not like what happened to the Alou card, but I must admit a strange attraction to it. Let’s take it a step further; this is actually one of my favorite cards from 1973 Topps. It has a surreal quality to it. The large logo and the seemingly oversized cap underscore Alou’s diminutive build; he was all of 5-foot-9, and while it’s hard to convey the size of a ballplayer on a baseball card, this one somehow does. Alou’s lack of height often became an issue with scouts, at least until he proved himself capable of handling the bat against big league pitching.

In retrospect, I guess that I also appreciated the card because it gave me my first look at Alou, one of my favorite ballplayers, wearing the uniform of the team that I first started following in the early 1970s -- even if that uniform was obviously airbrushed. For a young fan like me, it was exciting to see an accomplished veteran like Alou wearing the Yankee pinstripes after so many years in the National League.

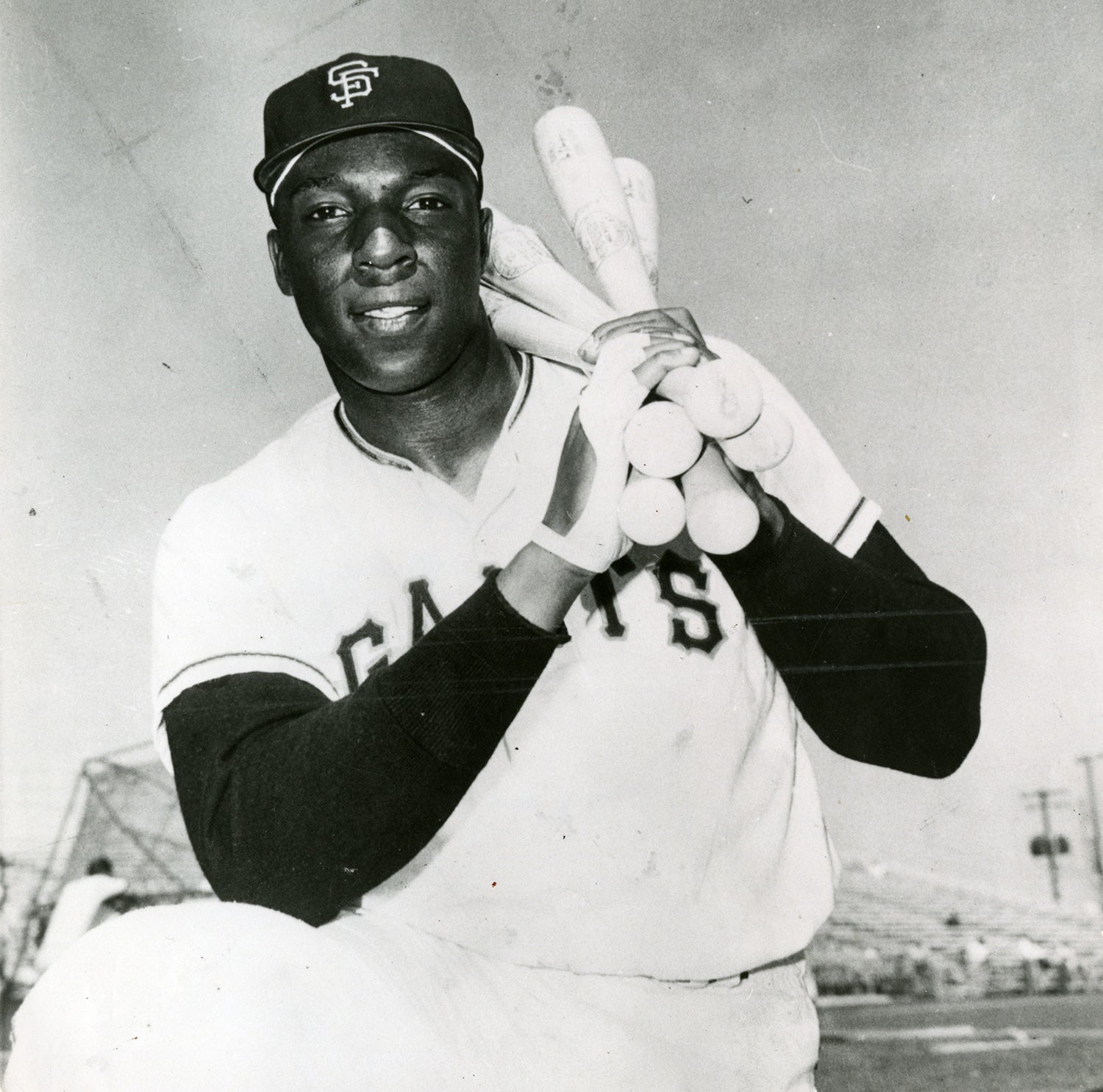

Alou’s stature, along with a completely unorthodox batting style, made him a fascinating player to watch in the 1960s and 70s. He broke pretty much every rule of hitting 101 to become a batting champion, a lifetime .307 hitter and a two-time All-Star. While he was not a superstar and was not the match of his supremely talented older brother Felipe, Matty Alou was a fine player. He could hit and run and field, and even toward the end of his career, was capable of helping a terrific A’s team win its first championship in Oakland.

Alou’s identity is also a source of interest. Like his brothers, Felipe and Jesus, he was always referred to as “Alou” during his career. But his name was actually Mateo Rojas Alou, with “Alou” being the maiden name of his mother (“Matty” represented an Americanized version of “Mateo.”). In Latino custom, the mother’s maiden name becomes one’s second last name, but that is often dropped in everyday usage. Given the cultural custom, Matty should have been called “Mateo Rojas.”

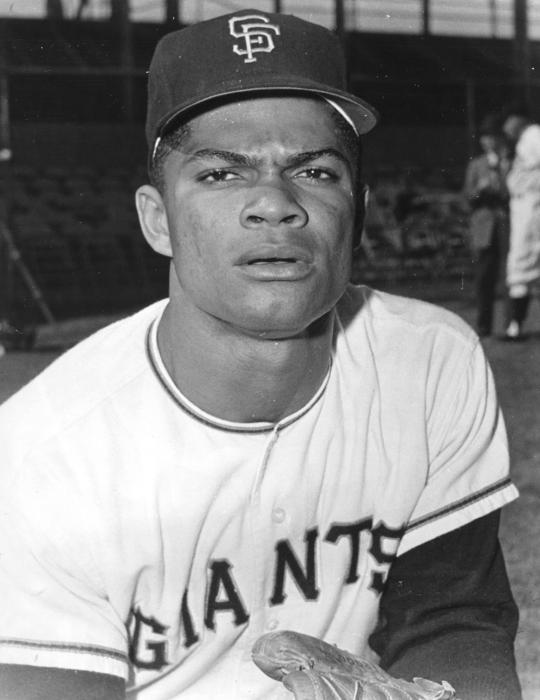

The confusion concerning his name stemmed from an earlier experience involving brother Felipe. When Felipe first came to the U.S. from the Dominican Republic, the San Francisco Giants’ scout who signed him listed him as “Felipe Alou” on his contract. As a result, the entire Giants’ organization came to know him as Felipe Alou, and the name stuck, at least in baseball circles. When Matty and Jesus signed with the Giants later on, they also became known by the last name of Alou. Rather than buck the trend, the Alou brothers simply accepted the name change.

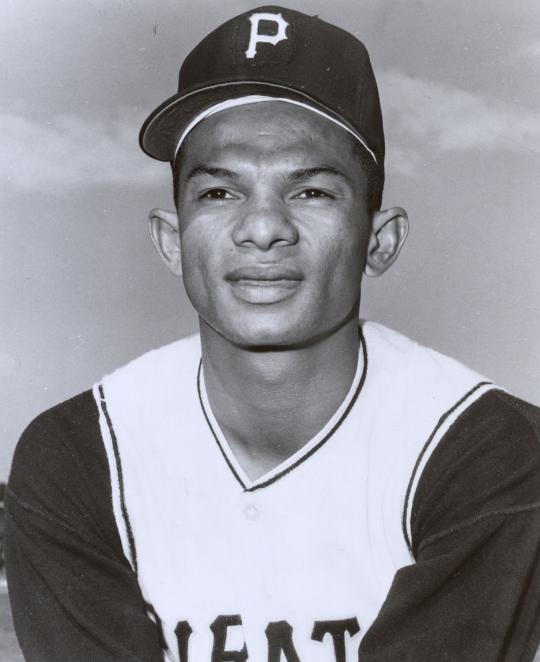

By any name, Alou signed with the Giants just before the start of the 1957 season, at a time when they were cultivating a connection to young talent in the Dominican Republic. The Giants assigned the 18-year-old Alou to Michigan City of the Midwest League, where he batted only .247 as a rookie but showed a decent eye at the plate. In 1958, he received a bump up to the Class C Northern League. That’s where he first started to show his hitting talent, putting up a .321 batting average and a .434 on-base percentage. Alou moved up to Class A Springfield of the Eastern League in 1959 and played well enough to advance all the way to Triple-A in 1960. After hitting .306 with 14 home runs for Tacoma, Alou received his first call-up to San Francisco. He appeared in four late-season games, a prelude to a full season with the Giants in 1961.

With Willie Mays and his brother Felipe ahead of him on the Giants’ outfield depth chart, Matty settled into a role as a backup outfielder that summer. He did well, hitting .310 in 200 at-bats. In 1962, his hitting fell off slightly, but a .292 batting average indicated that he could still handle National League pitching.

His final 1962 numbers tell only part of the story. During the Giants’ final seven games, Alou batted .510, helping the team finish in a first-place tie with the Los Angeles Dodgers. In the third game of the tiebreaker series with the Dodgers, Alou ignited the game-winning comeback rally with a pinch-hit leadoff single in the bottom of the ninth. Thanks in part to Alou, the Giants won the NL pennant. Alou continued to hit well in the World Series, but was left stranded at third base in Game 7, as the Giants fell just short of the Yankees on Willie McCovey’s line drive, which was caught by Bobby Richardson.

Then came the crash of 1963. Alou injured his knee playing in a Spring Training game, and the condition of his knee bothered him throughout the season. Appearing in only 63 games, Alou bottomed out as a .145 hitter, resulting in a temporary demotion to Triple-A. The Giants sent him back to Tacoma for a month, before bringing him back in September, but his season-long slump continued.

If there was one highlight to the 1963 season, it was the events of Sept. 15. On that day, manager Alvin Dark made a midgame maneuver that allowed Matty and his two brothers to play in the same Giants outfield, making history. They would never again have the chance to do so, with Felipe being traded after the season.

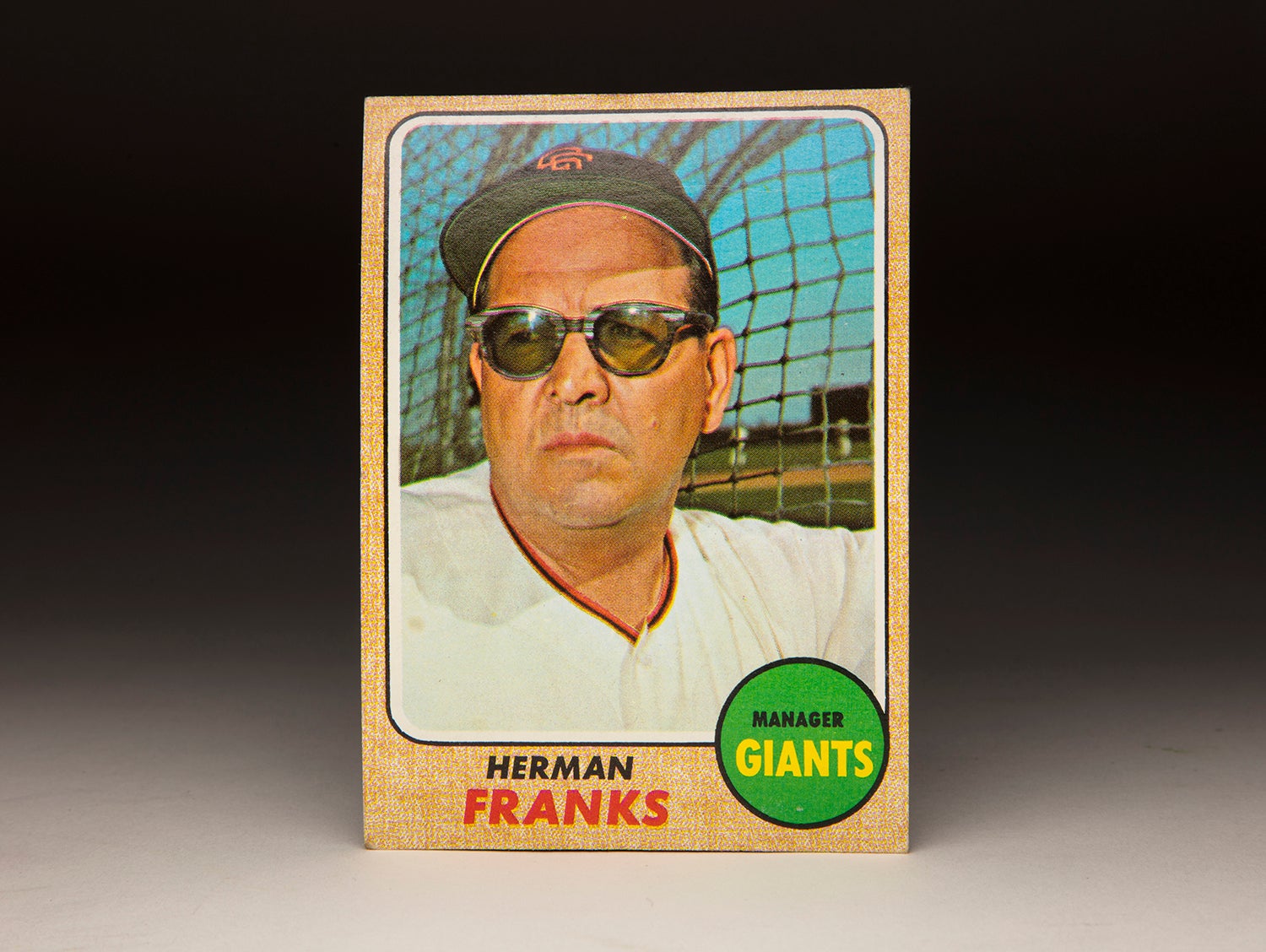

In 1964, Alou again settled for a backup role on a team filled with quality outfielders. He started the season slowly and then incurred another injury – this time a broken bone in his wrist. He missed five weeks of the season and hit better after his return, but could only manage to raise his batting average of .264. Alou found an increased role waiting for him in 1965 – a chance to play regularly for new manager Herman Franks. But Alou did not hit, compiling only a .231 batting average. Alou blamed only himself; he felt as if Franks had given him every chance to perform.

The disappointment of the 1965 season resulted in a change. That December, the Giants gave up on Alou, trading him to the Pittsburgh Pirates for utilityman Ozzie Virgil and left-hander Joe Gibbon. The trade would end up being the piece of good fortune that Alou needed. Pirates manager Harry Walker believed that Alou needed to completely retool his approach at the plate. He told Alou to use a heavier bat, one weighing 38 ounces, while emphasizing the importance of swinging down on the ball and hitting toward the opposite field. The approach worked like a miraculous charm.

In 1966, Alou batted .342, good enough to win the National League batting title and a remarkable increase of 111 points over his average in 1965. Alou’s hitting garnered the attention of National League writers, who placed him ninth in the MVP balloting at season’s end. To many observers, Alou’s style looked strange. He strode early with his lead foot, kept his bat back as long as possible, and tried to flip the ball into left field. With his front-foot style of hitting and his tendency to swing at pitches out of the strike zone, Alou’s unorthodox manner caught the attention of other players, both active and retired, including Ted Williams. As Williams once told the Sporting News about Alou: “He violates every hitting principle I ever taught.”

And yet, it worked. Over his next three seasons in Pittsburgh, Alou batted .338, .332, and .331, respectively. He made the All-Star team in both 1968 and ’69, and received consideration for National League MVP each season. With aggressive hitters like Alou, Roberto Clemente, Manny Sanguillen and Al Oliver, the Pirates gained a reputation for hard hitting and free swinging.

Alou was also proficient at playing “little ball” aspects of the game. Scouts generally regarded him as the best bunter in the National League. He also became adept at executing the hit-and-run, largely because he rarely swung and missed at pitches. He ran fast, too, although his stolen base percentage often fell below the 70 percent range.

It was not until 1970 that Alou started to show any decline in his game. His batting average fell to .297 and his OPS to .685. The Pirates also became concerned with his diminishing range in center field. Deciding that the time was right to make room for Oliver in center field, and given their need for starting pitching, the Pirates shopped Alou that winter.

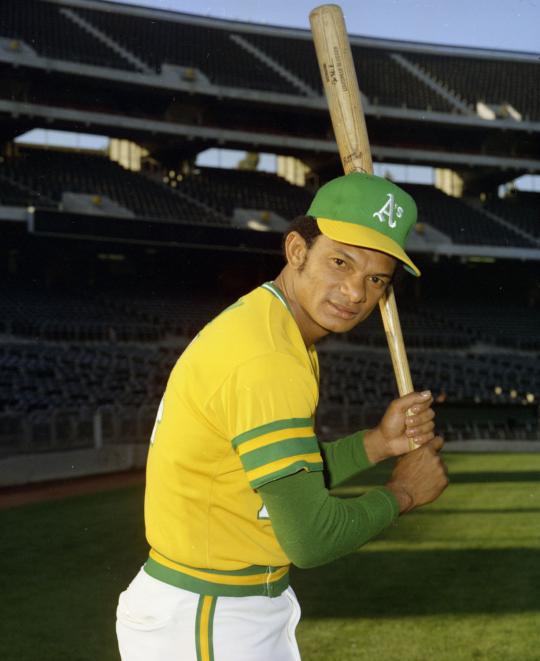

Captured by Topps photographer Doug McWilliams during his time with the Oakland Athletics in 1972, Matty Alou was a stretch-drive acquisition by A's owner Charlie Finley. Alou helped the A's win their first World Series title that year, appearing in all 12 of the team's postseason games. (Doug McWilliams/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

They sent Alou and left-hander George Brunet to St. Louis for a package of right-hander Nellie Briles and backup outfielder Vic Davalillo. The trade rejuvenated Alou, who found the newly installed AstroTurf at St. Louis’ Busch Stadium to his liking. He not only batted .325, but also hit seven home runs, the best output of his career. The Cardinals also challenged him to be more versatile, using him in center field, right field and at first base.

Alou hit well again in 1972, but the Cardinals quickly fell out of contention and decided to trade off their productive but aging veteran. They sent him to the A’s for another outfielder, Bill Voss, and a minor league throw-in. The A’s had Joe Rudi in left and Reggie Jackson in center, but desperately needed a productive hitter who could play right field. The A’s decided that Alou could fill the bill.

On the surface, Alou’s .688 OPS with Oakland would seem unimpressive. But he came up with several key run-scoring hits during the stretch run, helping the A’s stave off the Chicago White Sox for the Western Division title. Alou then hit .381 in the ALCS, as the A’s beat back a veteran group of Detroit Tigers on their way to winning a world championship over Cincinnati.

As well as Alou played for the A’s, he made a large salary for the time period – exactly $100,000. Not wanting to pay Alou a six-figure salary to be a platoon outfielder, owner and general manager Charlie Finley traded Alou that winter, sending him to the Yankees for a less expensive player, pitcher Rob Gardner. The trade reunited Matty with older brother Felipe, who had been with the Yankees since the early days of the 1970 season.

The Yankees made Matty their Opening Day right fielder and No. 3 hitter, but when they fell out of the pennant race in September, they decided to move him out. In fact, they sold off both of the Alou brothers, on the same day no less. The Yankees sent Felipe to Montreal on waivers and Matty back to St. Louis in a straight cash transaction. The Cardinals used Alou as a pinch-hitter during the stretch run. After the season, they sold him to San Diego, where he finished out his major league career in 1974.

Discarded by the Padres with a .198 batting average in July, Alou decided to continue his career in the Japanese Leagues. Alou did not particularly like playing in Japan, mostly because of excessive practice and travel schedules. He hit .312 in his first season with Taiheiyo before falling off in production the next two.

His playing days over, Alou eventually returned to the game as a scout. He worked for the Detroit Tigers and Giants, before retiring in the early 2000s due to health concerns. In 2011, Alou died from complications brought on by diabetes at the age of 72. One of the players who remembered him was Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda, his onetime teammate in San Francisco. “We roomed together a few times with the Giants,” Cepeda told the Associated Press. “Very funny guy, hell of a ballplayer.”

Like many fans of baseball from his era, the news of Alou’s death saddened me. I also regretted never having met him. If I had, would have expressed my thanks for providing so many good memories, for his fun style of play, and for the way that he showed that there is plenty of room for the little guy in our great game.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame