- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Rich McKinney

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Rich McKinney

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

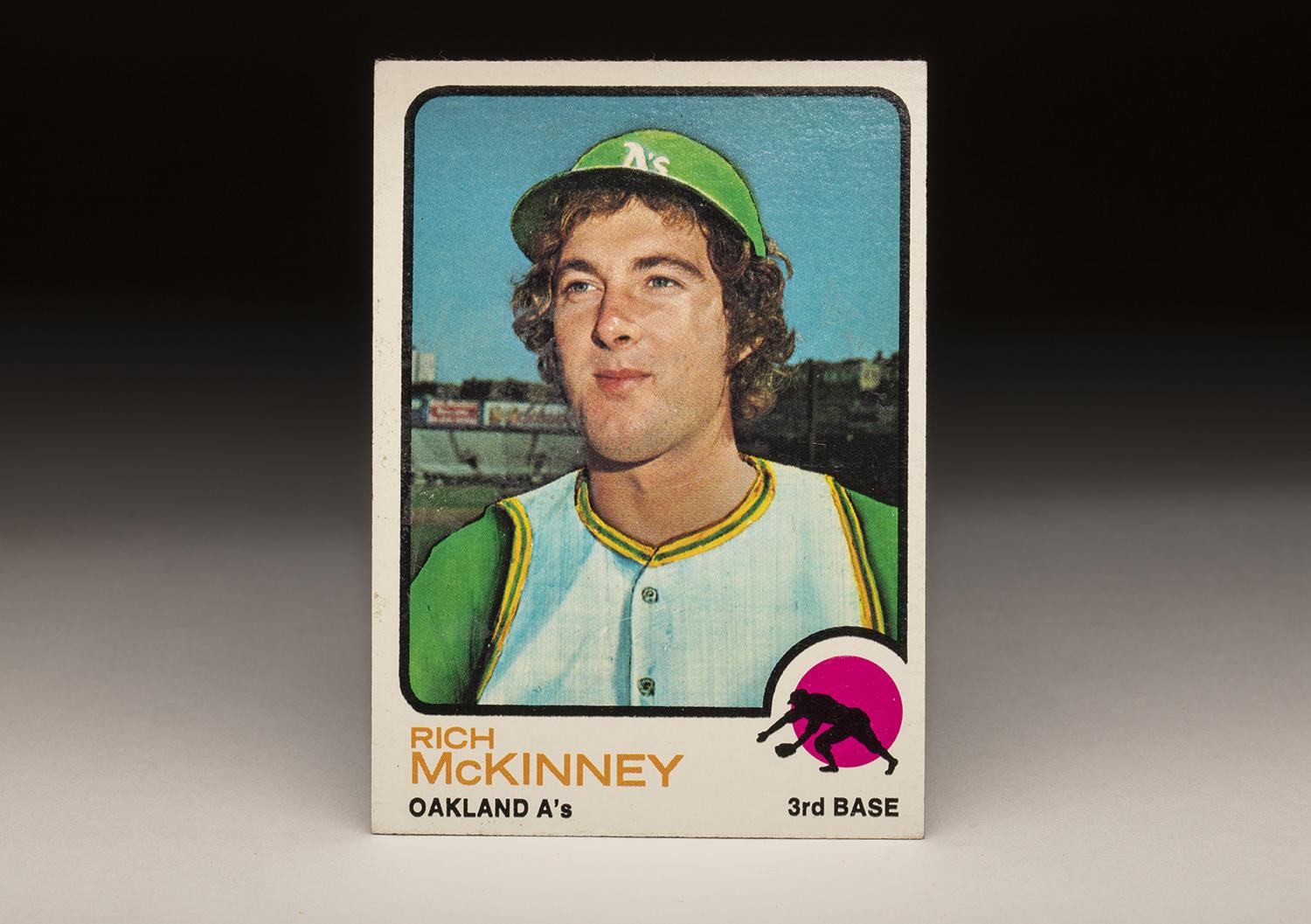

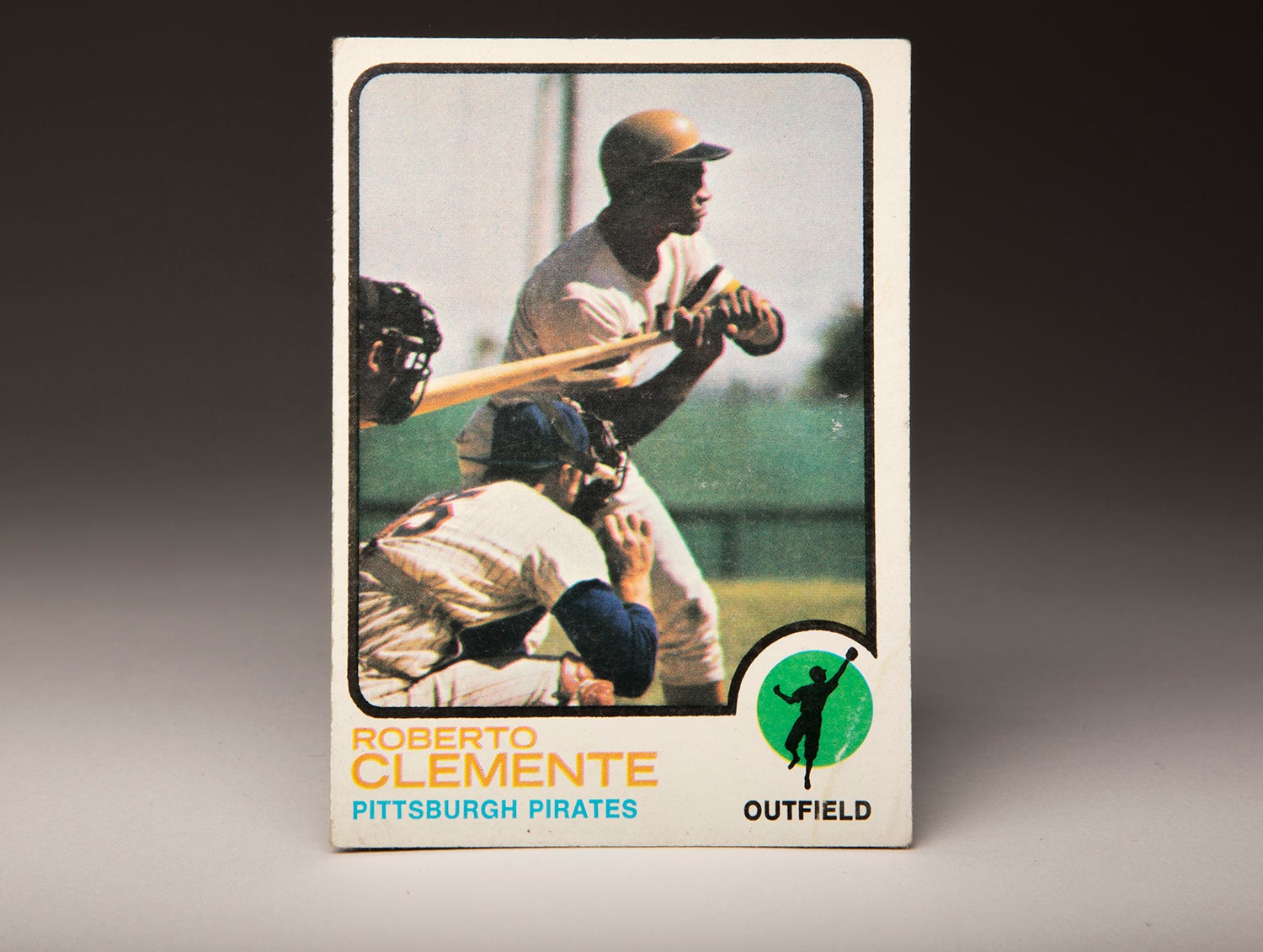

With few exceptions, I enjoy the cards featured in the 1973 Topps set. With its simple design, preponderance of action shots and that groovy-looking shadow figure transposed against a colored circle, 1973 Topps has a look and feel that has made it popular with collectors. Yet that doesn’t mean that every card in the set is attractive in a logical or traditional way.

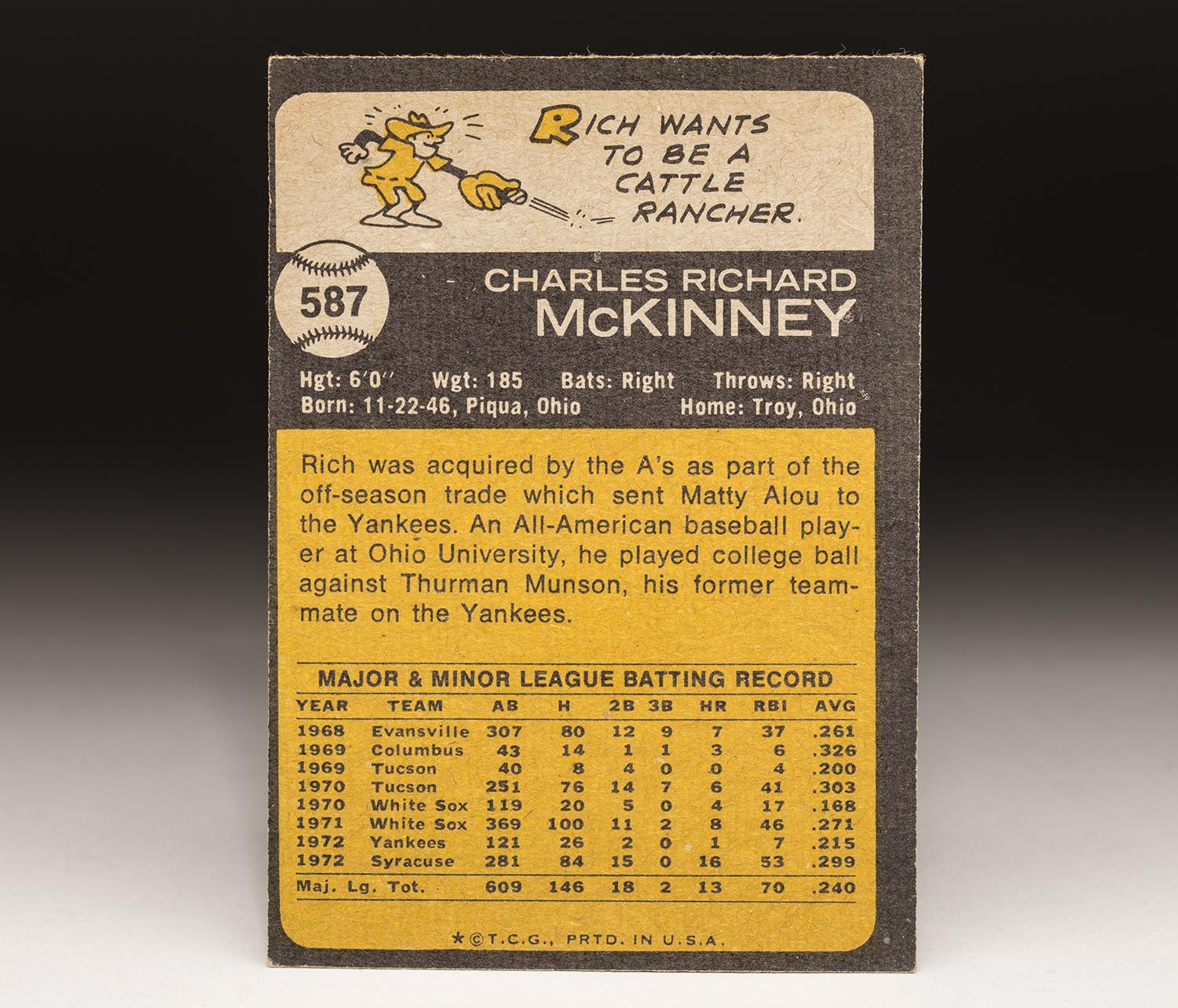

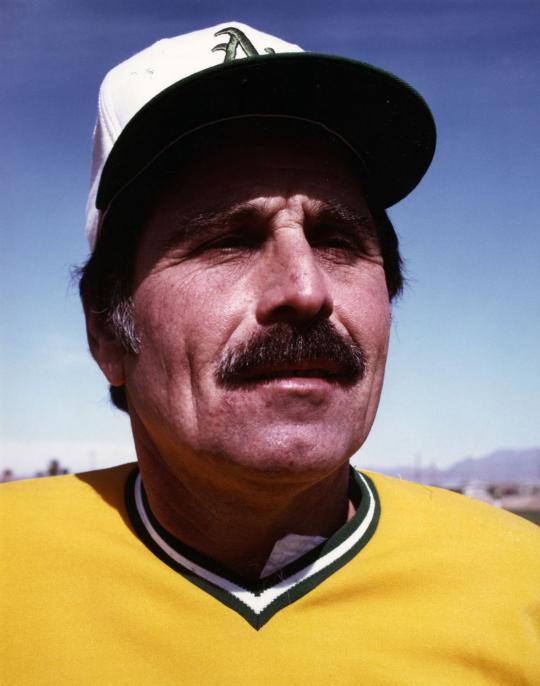

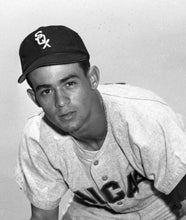

An example can be found in the Rich McKinney card. As you can see, the former big league third baseman was one of the wilder looking athletes of the 1970s. He had a large chin, one that was reminiscent of actor Bruce Campbell and comedian Jay Leno in today’s popular culture. McKinney also had long, curly hair – a 1970s perm that some cultural observers have nicknamed the “white Afro.”

In order to accommodate the fact that he had been traded from New York to Oakland during the winter, an artist at Topps airbrushed a strangely shaped green helmet onto McKinney’s head, and included green sleeves and gold piping on the jersey. There is something a bit unusual about the style of uniform that Topps chose to airbrush. For some reason, the Topps artist airbrushed Oakland’s old sleeveless jersey onto McKinney, rather than the new pullover jersey that the A’s had adopted in 1972.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

When you couple the airbrushing with McKinney’s prominent chin and curly hair, you have one of the more unusual looking cards of the era. The card is one of the reasons why McKinney remains known to collectors. And it’s a card that I happen to love for all of its weirdness.

Unless you are a collector, it’s quite possible that you have little to no memory of Rich McKinney. That’s because his career lasted only for a fleeting few moments in the grand scheme of baseball’s historical timeline. But there’s more to McKinney than being a journeyman player who didn’t quite live up to expectations.

McKinney’s journey, and how he ended up in Oakland for the 1973 season, is worth exploring. As a high school senior, McKinney suddenly became ill with a high fever, lost 40 pounds and nearly died. At one point, the doctors suspected that leukemia was the cause but later ruled out that diagnosis. The doctors never did pin down what McKinney had contracted.

After starring initially as a catcher during his high school years, McKinney was converted to shortstop in college; it was a position with which he never felt completely uncomfortable. In spite of the position change, the Chicago White Sox made McKinney their first-round pick (14th overall) in the 1968 MLB Draft. As a first-round pick, he seemed like a blue chip talent destined to become a star for the White Sox. But the Sox continued to tinker with his position in the field. During his first minor league season, they moved him from shortstop to center field.

In order to accommodate the fact that he had been traded from New York to Oakland during the winter, an artist at Topps airbrushed a green helmet onto Rich McKinney’s head, and included green sleeves and gold piping on the jersey. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Within two years, he arrived in Chicago. Called up in the middle of the 1970 season, he made his major league debut on June 26. Rather strangely, he played third base, a position that he had never played previously. In total, McKinney played in 43 games as a third baseman and shortstop. For the most part, he was blocked by two capable veterans: Beltin’ Bill Melton at third base and Hall of Famer Luis Aparicio at shortstop. McKinney also didn’t hit much, so his future in Chicago seemed murky.

In 1971, McKinney remained in a utility role, but he hit well and earned more playing time. The Sox no longer used him as a shortstop, but found time for him at third base, second base and the outfield. In particular, McKinney expressed gratitude for the move to the outfield – and for not having to play shortstop anymore.

“I don’t believe I have the ability to play shortstop in the major leagues,” McKinney said as part of a brutally honest assessment to the Sporting News. “I just don’t have the range and I don’t do too well with the pivot. They had Luke Appling work with me, but I don’t feel that’s the spot for me. I’m in the right place now: The outfield. You don’t have so many different plays to worry about out there and, therefore, can concentrate more on your hitting.”

McKinney’s offensive numbers supported the claim that the shift in positions had made it easier for him for hit. For the season, he batted .271 with eight home runs, and he posted an OPS of better than .700. As a pinch-hitter, McKinney performed at a superhuman level. In 19 pinch-hit at-bats, he delivered 11 hits, good for a .579 batting average. All in all, McKinney’s improved hitting caught the eye of White Sox management, along with scouts for other teams.

McKinney’s hitting drew plenty of praise from his manager, Chuck Tanner. “Oh, McKinney, he’s something else,” Tanner gushed in an interview with Jerome Holtzman. You just put his name in the lineup and he’ll hit .300 for you. He’s a natural born hitter.”

As much as Tanner liked McKinney’s hitting potential, he struggled to find him regular playing time. With Melton entrenched at third and reliable Mike Andrews ready to play second base, McKinney remained blocked from everyday duty. That winter, some Chicago writers speculated about a trade. Rather than trade Andrews or Melton, why were slightly older, the White Sox decided to trade McKinney. After the 1971 season, the White Sox sent him to the Yankees for veteran right-hander Stan Bahnsen.

Almost from the start, the deal was panned by Yankee fans. They didn’t know much about McKinney. While McKinney had excelled in a pinch-hitting and backup infield role for the ’71 White Sox, he had never been an everyday player and had never exhibited the defensive skills needed to play third base on more than a part-time basis. For this, the Yankees parted with Bahnsen, a reliable starter who filled a vital role as the team’s No. 3 starter behind Mel Stottlemyre and Fritz Peterson. (Yankee fans would become even more upset with the trade in 1973 when Bahnsen won 21 games for the White Sox.)

Yankee fans also became concerned when they heard about an incident involving McKinney. While playing Winter Ball in Puerto Rico, where he hoped to gain experience as a third baseman, McKinney attended a beach party. He suffered third-degree burns on his ankle, the result of coming into contact with a charcoal fire.

The burns were so bad that McKinney said his foot looked like “pizza.” Unable to sleep for three straight nights, McKinney finally went to the hospital, where a doctor removed the damaged skin. For the next two weeks, McKinney stayed in bed.

Still, Yankee management had high hopes for McKinney. They expected McKinney to fill the third base void that had been created five years earlier by the trade of Clete Boyer to the Atlanta Braves. Ever since, the Yankees had been searching for a quality third baseman. They felt that McKinney would end the search. In short, the Yankees considered McKinney their marquee acquisition of the offseason.

As such, the Yankees used McKinney in promotional efforts for the 1972 season. They featured McKinney as part of their old wintertime caravan into Upstate New York, Connecticut and Pennsylvania. As the caravan began, the Yankees showcased McKinney as their new arrival – and key piece for the 1972 season.

Unfortunately, the caravan did not go as smoothly as the Yankees would have liked, particularly when McKinney asked Yankees public relations official Marty Appel an inappropriate question about marijuana on the very first day of the winter tour.

Once the regular season began, after the first strike in MLB history came to an end, reality soon set in with regards to McKinney’s playing ability. McKinney became the Opening Day third baseman, but his first week in pinstripes did not go well. On Saturday afternoon, April 22, with the season less than a week old, the Yankees played the rival Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park. McKinney had a great game at the plate that day, coming up with three hits in four at-bats, including his first home run as a Yankee.

Yet, no one remembers any of that. In trying to field his position, McKinney made four errors at third base, two coming in the first inning. The four errors contributed to a total of nine unearned runs scoring. The Yankees lost the game, 11-4. With better fielding from McKinney, the Yankees might have actually won the game.

After the game, McKinney again answered questions with his trademark brutal honesty. “They were all so easy, so easy,” McKinney said to Yankee beat writer Jim Ogle. “If they had been tough chances, I wouldn’t feel so bad, but I couldn’t find the handle. It just kept getting worse until I was hoping that no one else would hit the ball to me.” McKinney chose not to use the condition of his right elbow, which featured a floating bone chip, as an excuse for his poor fielding display.

After the game, two veteran Yankees, infielder Bernie Allen and Johnny Callison, took McKinney out to dinner as a way of trying to help him forget about his nightmarish game. The night went well, at least until the three players returned to their rooms in the Yankees’ hotel. That’s when McKinney turned on a TV and watched the local newscast replaying the highlights from that day’s game. Those “highlights” included McKinney’s four errors at third base.

McKinney actually settled down defensively after that game, but his hitting soon fell by the wayside. At one point, McKinney admitted to having trouble sleeping and said that “every lampshade [in the room] looked like a pitcher.” On a Sunday in late May, McKinney heard repeated rounds of boos from the fans at Yankee Stadium. The next day, with his batting average having sunk below .220, McKinney received word of a demotion. The Yankees told him that they were sending him to Triple-A Syracuse, where they hoped that he could regroup mentally.

By his own admission, McKinney wanted no part of the minor leagues. “I came here (to Syracuse) with a bad attitude and didn’t want to play,” he told the Sporting News. “But manager Frank (Verdi) had a long talk with me and made it clear I’d better work or he’d get rid of me.” Verdi’s talk worked. McKinney played well at Syracuse, batting .299 with 16 home runs over the balance of the season.

When rosters expanded in September, McKinney received a call-up to the Yankees. But there was no regular playing time waiting for him. He played sporadically, but failed to raise his batting average, and did not hit with much power. By season’s end, his numbers looked paltry. His slugging percentage was a meager .256, while his on-base percentage was not much better at .258. Defensively, McKinney put up a fielding percentage of .917, a simply unacceptable mark for a third baseman.

To the surprise of few, the Yankees cut ties with McKinney after the season. In December, they announced that McKinney would be heading to the Yankees as the player to be named later in the trade that sent Matty Alou to New York. Just one year after being the Yankees’ most heralded acquisition, McKinney was now an ex-Yankee. Topps now scrambled to take a pre-existing photograph of McKinney and airbrush the A’s’ green and gold colors over the existing Yankees uniform.

McKinney was thrilled by the trade. He had always dreamed of playing for a West Coast team, and now had that chance. He was also joining the defending world champions, who had just defeated the Cincinnati Reds in a seven-game World Series.

Believing in McKinney’s bat the way that Tanner once did with the White Sox, the A’s found room for McKinney on their Opening Day roster in 1973, using him as a fill-in infielder, outfielder, and occasional DH. McKinney took a liking to the new DH rule, which he compared to being a “field goal kicker in football.”

The A’s hoped that McKinney would provide some punch off their bench, but he batted only .245 in a reserve role. By July, he was back in Triple-A, only to be recalled in September. McKinney was not included on Oakland’s postseason roster.

Other than brief stints with the A’s in 1974 and ’75, McKinney spent most of the next three seasons at Triple-A Tucson, where he hit for both average and power. No longer considered a prospect, McKinney considered retiring from baseball and opting for a job with a trucking company. Then out of the blue, he received a phone call from Oakland owner Charlie Finley, who urged him to report to Spring Training in 1977 and promised him a real chance at playing under new manager Jack McKeon. Sure enough, McKinney made the Opening Day roster and spent the majority of the season in Oakland. He batted only .177 but did hit six home runs, his best output since 1971.

Now 30 years old, McKinney decided to retire. He became a professional truck driver for a few years before changing course and running a farm with his father. After that, he took a job with Panasonic, working in their manufacturing division.

Although McKinney’s playing career became a disappointment, he did leave some vivid impressions with his personality and behavior. Teammates nicknamed him “Orbit,” a label that he earned for being aloof and offbeat. (Hey, when you make four errors in a game, it helps to be a little offbeat.) McKinney happened to share the nickname with former Kansas City Royals and Seattle Pilots outfielder Steve Hovley, one of the most memorable of Jim Bouton’s strange cast of characters from Ball Four.

It’s too bad that McKinney isn’t an active player today. His refreshing honesty would make him a popular presence on social media. I imagine he’d have some funny stories, too, about his short but tumultuous career in baseball. Additionally, he might have a few honest thoughts about his unusual 1973 Topps card, which first hit stores some 45 years ago.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame