- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1974 Topps Carlos May

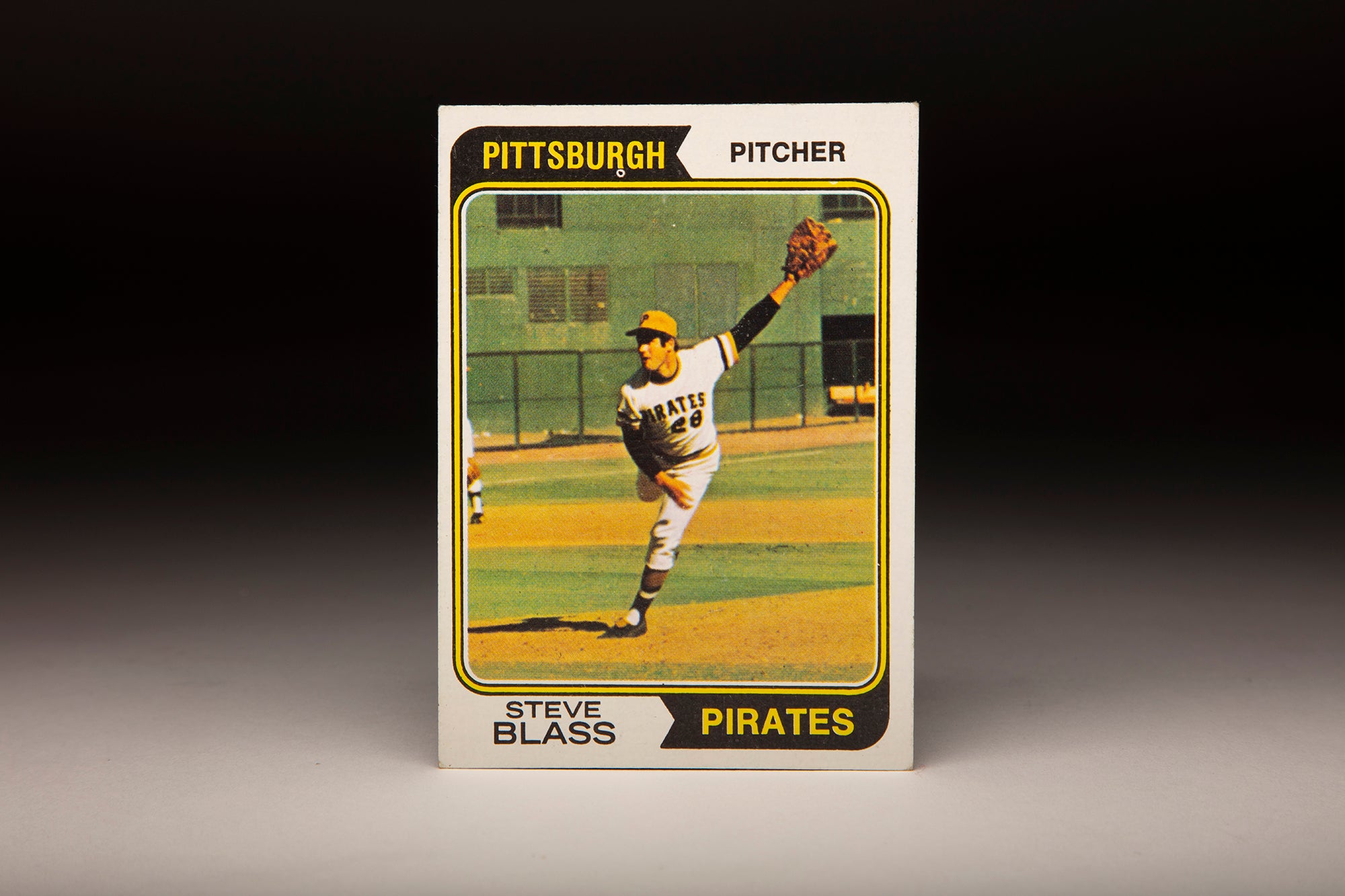

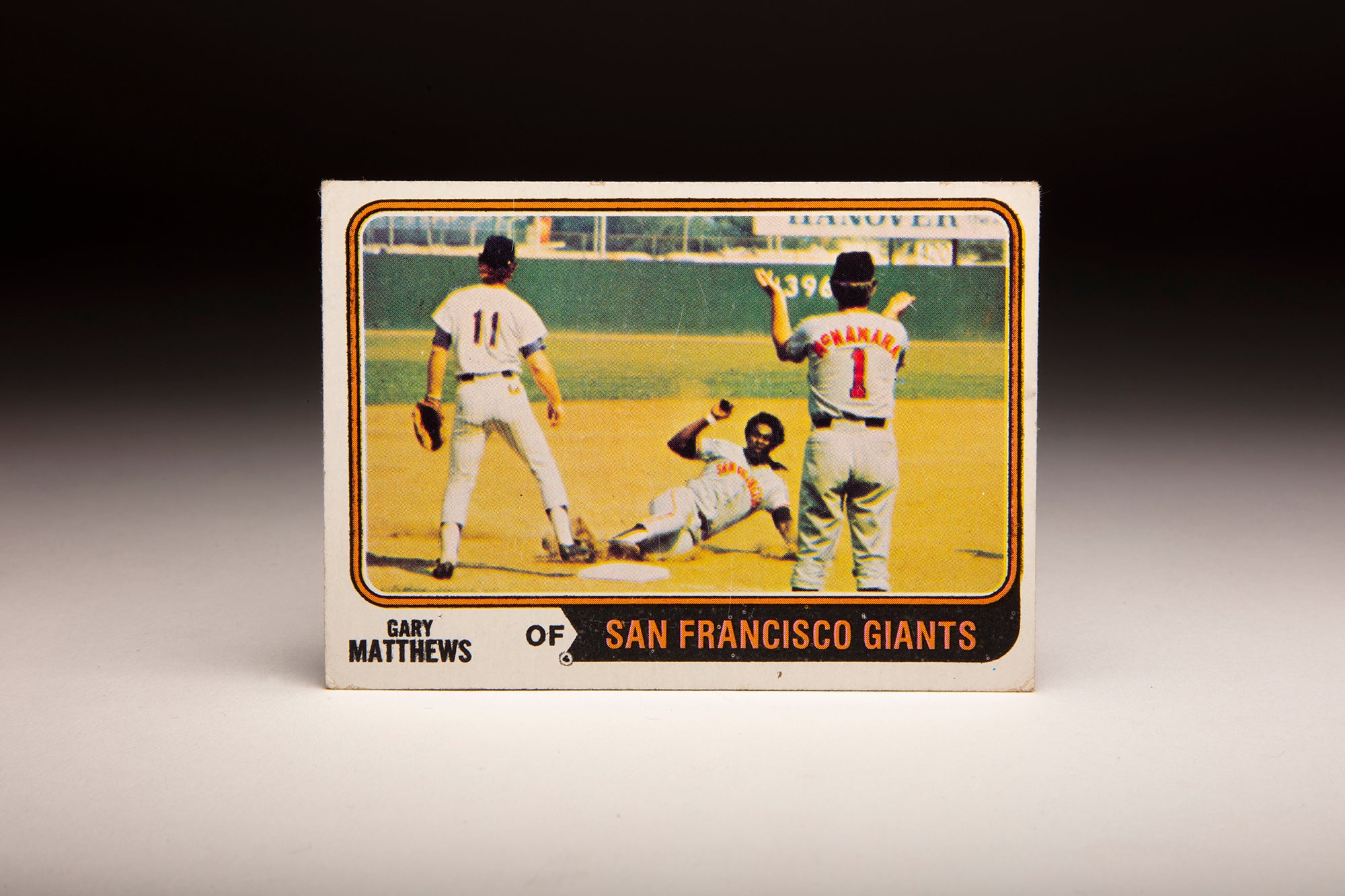

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Carlos May

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Every once in a while, Topps will show us a player in the on-deck circle. Granted, it’s not as glamorous as seeing a player during an actual at-bat, but there is a certain anticipation that comes with a player who is next in line to do battle with the pitcher.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

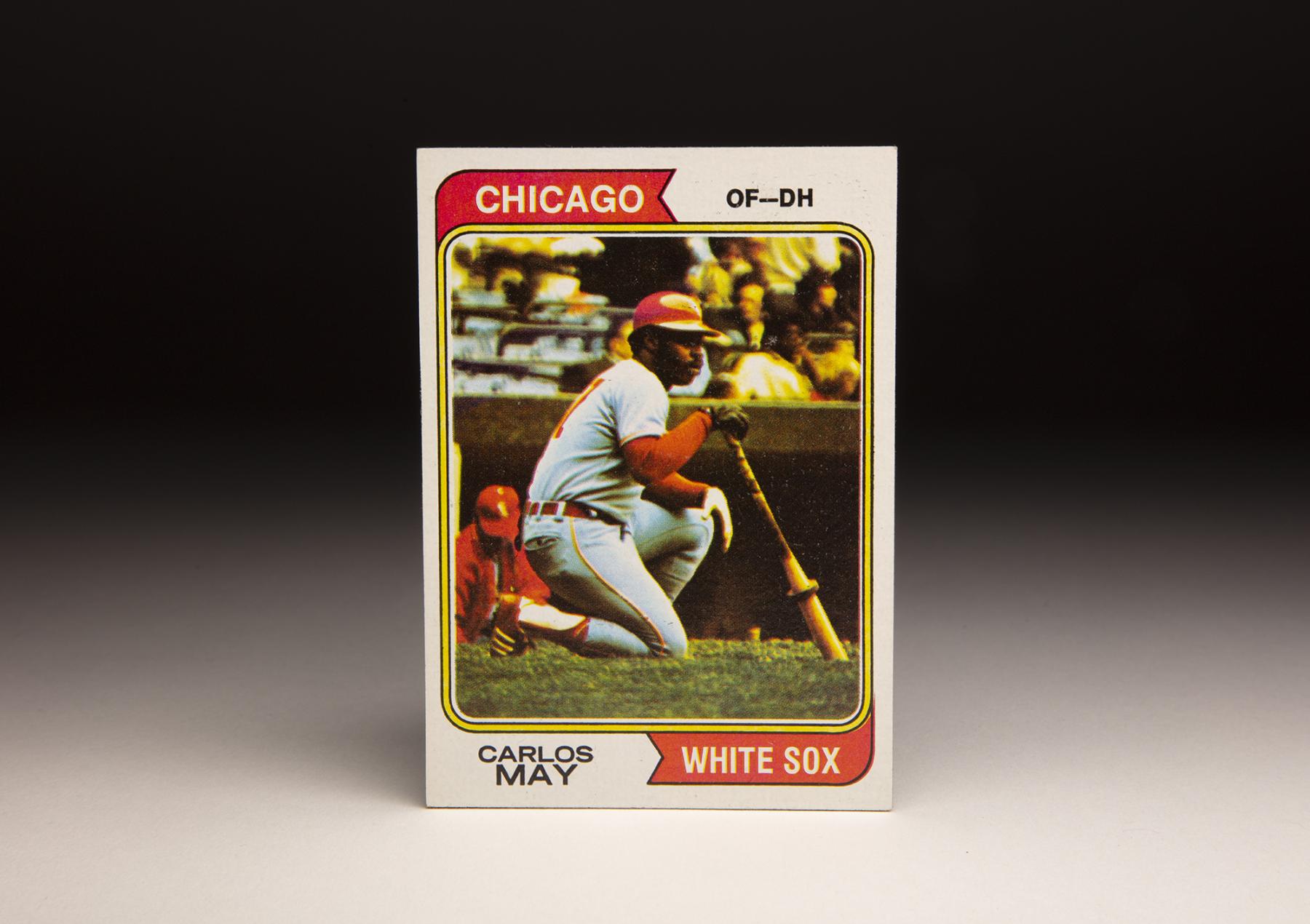

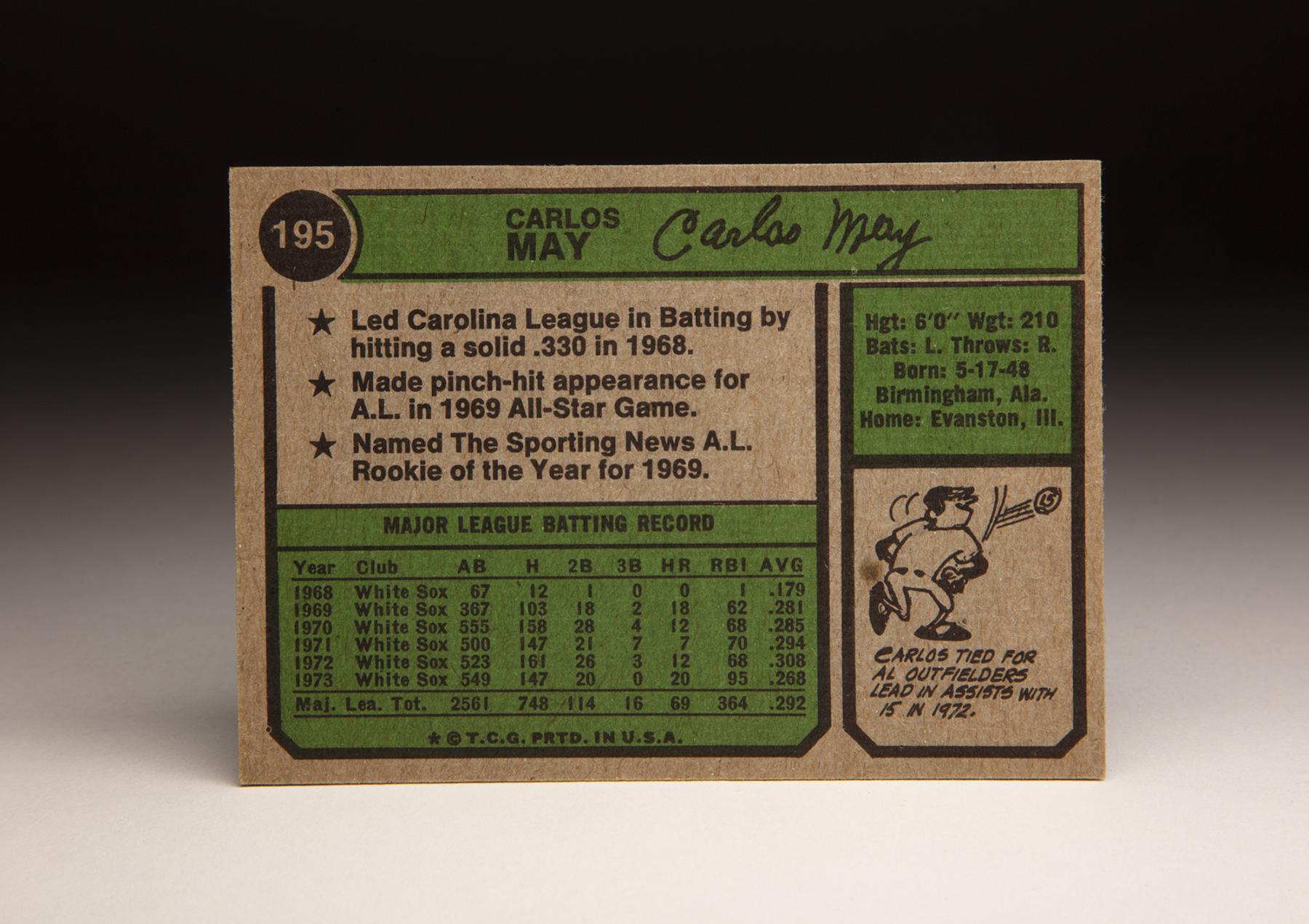

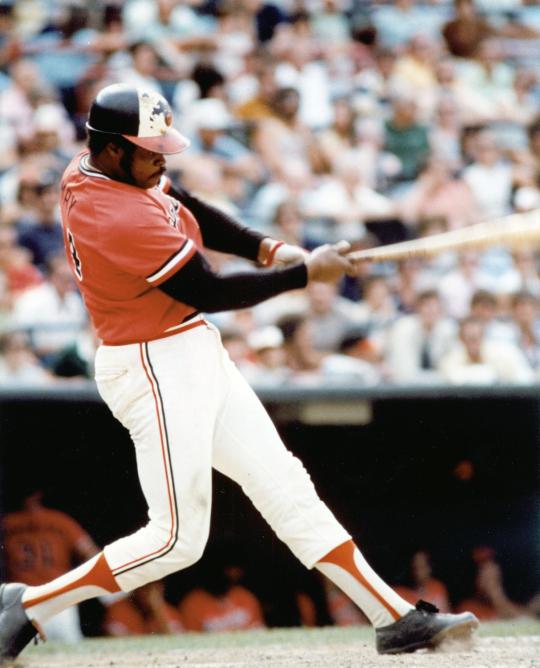

The 1974 Topps set features four cards of players who are on deck during actual games: Horace Clarke, Hal Lanier, Carlos May and Dave Nelson. All four players have interesting backstories, but let’s focus on May, whom we see wearing the powder blue road uniform of the Chicago White Sox.

Down on one knee, May is resting his left arm on his left thigh, while his right hand is holding onto the knob of his bat, propping it at a diagonal angle. Notice the darkness of May’s bat; it appears to be slathered in pine tar, perhaps beyond the 18-inch limit allowed by the rules. It also features an old-fashioned donut on the barrel. The batting donut was invented in the 1960s by Elston Howard as a way of adding weight to the bat during a batter’s practice swings.

Of particular interest are May’s hands. He is wearing batting gloves on both hands, but the gloves are hardly a matching pair. The one on the left is a bright white, so pristine that it looks like it could be brand new. In contrast, the glove on the right hand is black, and does not appear to be in such perfect condition. It is also covering the hand that drew far more attention during the later stages of May’s career. Why? It was that right hand that was badly damaged as the result of an injury. It happened a few years earlier, during the Vietnam War.

May never saw actual service time in Vietnam, but found some unwanted action during a stateside stint. While stationed as a Marine at Camp Pendleton during the summer of 1969, May was swabbing out mortars when one of them misfired. The mortar shell literally blew off part of his right thumb. It was a frightful injury, one that could have killed May under slightly different circumstances. As it was, the incident resulted in May being rushed to the hospital.

Just a few years earlier, Carlos May was one of the most highly touted amateur players in the country. In 1966, the White Sox took the lefty-swinging outfielder with the 18th selection of the MLB Draft. The White Sox assigned the native of Birmingham to their Rookie League affiliate in the Gulf Coast League, where he dialed up opposing pitching at a .426 clip. After only 16 games there, the Sox promoted him to the Florida State League, where the pitchers proved more problematic. In 37 games, May batted just .153.

By 1967, May was more acclimated to the professional game. Assigned to the Midwest League for a full season, he batted .338 with 10 home runs. Even more impressively, he showed remarkable bat control, as evidenced by a walk total that nearly doubled his strikeout count. May struck out only 24 times, while drawing 45 walks.

In 1968, the White Sox resisted the temptation to try May out at Double-A, instead keeping him in Class A ball, this time in the Carolina League. He continued to hit for average, but also with more power. For the season, he hit 13 home runs. He also continued to draw walks more frequently than he struck out. The White Sox were so impressed that they brought him to Chicago in September, giving him 17 games and 67 at-bats against American League pitching.

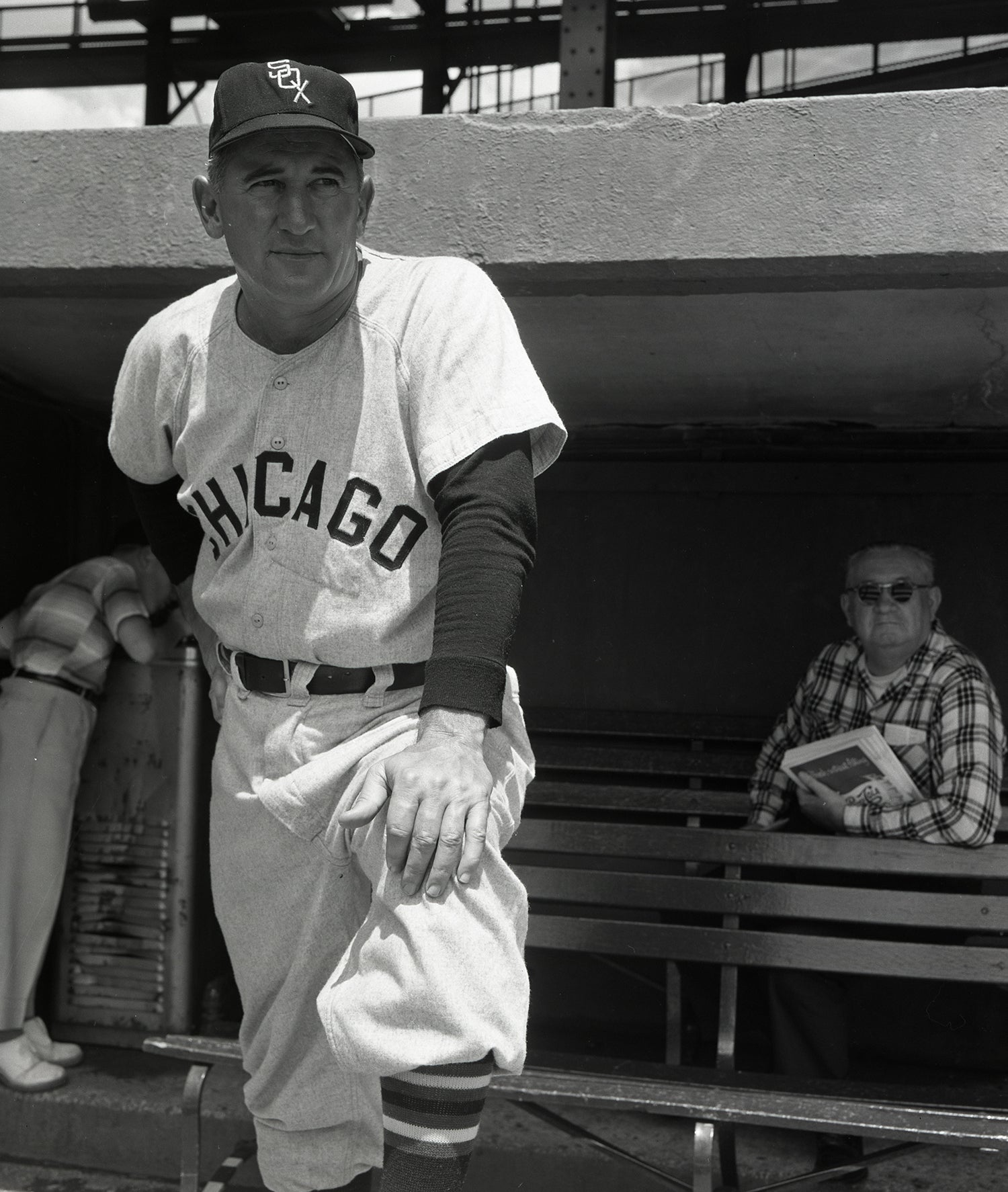

Double-A ball would have seemed like a logical destination for May in 1969, but the White Sox bypassed that level of minor league play. In fact, they bypassed Triple-A, too. To the shock of some, May made the White Sox’ roster out of Spring Training. On Opening Day, manager Al Lopez, the future Hall of Famer, inserted May into the starting lineup as his left fielder and No. 2 hitter behind Luis Aparicio. May became the second member of his family to make the major leagues, joining his brother, Lee May, a slugging first baseman with the Cincinnati Reds.

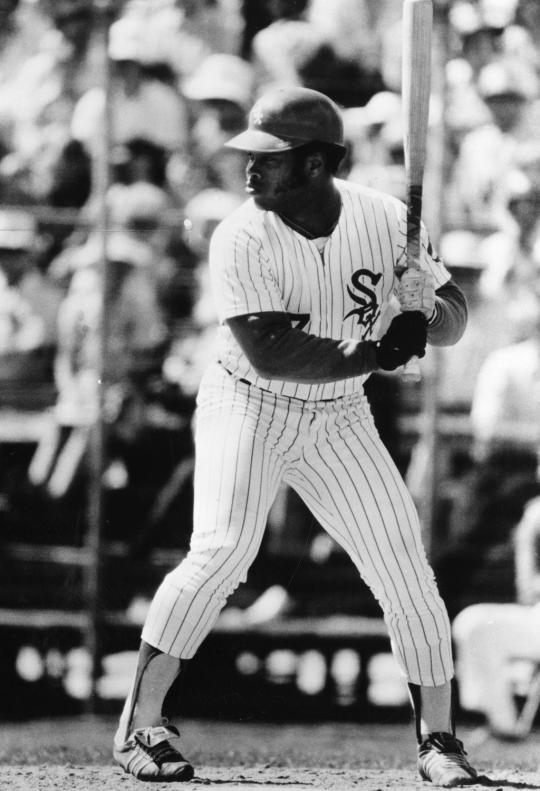

Just 20 years old, May became the White Sox’ regular left fielder. Even after the White Sox changed managers, replacing Lopez with Don Gutteridge, May remained in the lineup on a consistent basis. He struggled at time with his fielding chores, but at the plate, he excelled. Through August, he was batting a robust .281 with 18 home runs and 58 walks. His OPS stood at an impressive .873.

Gutteridge, his new manager, took note of May’s enthusiasm for hitting while making the ultimate in comparisons. “He really loves to hit,” Gutteridge told Ed Rumill of the Christian Science Monitor. “In that respect, he reminds me of Ted Williams.”

In August came news that the hot-hitting May, now a leading candidate to win Rookie of the Year honors, would have to report for two weeks of military reserve training with the U.S. Marines. He received his assignment: Camp Pendleton, located in San Diego County in California.

On a particularly hot afternoon, May and the other Marine reservists were told to practice the handling of mortar weapons. As part of the task, each man had to swab out the mortar gun with what is known as a ramrod. As May reached in with the ramrod, a mortar exploded, tearing off part of his right thumb. Taken to a local emergency room, May had to have part of his thumb amputated and then several skin grafts done. Three days later, May vowed that he would return to play baseball again.

The Marines officially assessed the injury as a “50 percent disability,” meaning that his military career had come to an end. It also appeared to some that the injury would ruin his baseball future. Some scouts felt that May would never be able to play again. They would need to think again.

When the White Sox opened up Spring Training in February of 1970, May reported on time. He soon took batting practice and impressed American League President Joe Cronin, who happened to be in attendance that day.

“He really looks good,” Cronin told the Associated Press. “Honestly, I never thought he would be back, but it looks as if he’s going to make it.”

After taking batting practice, May reported that there was no bleeding coming from the thumb, but explained that it had to be bandaged in order to stave off an infection. He also needed to rest the thumb for several days before having another batting practice session. May would repeat that pattern several times, until the newly grafted skin hardened on his thumb.

Later in Spring Training, May encountered a different kind of setback when he felt soreness in his back. But the back pain lasted only a few days, allowing May to resume batting practice and play in actual spring games. Against most odds, May not only made the Sox’ regular season roster, but also worked his way into the Opening Day starting lineup.

As he stepped into the batter’s box for the first at-bat of the season, May received a standing ovation from the fans at Comiskey Park. May flied out to left, but later picked up a hit to finish at 1-for-4. He then went on a minor hitting tear. By the end of April, May was hitting .290.

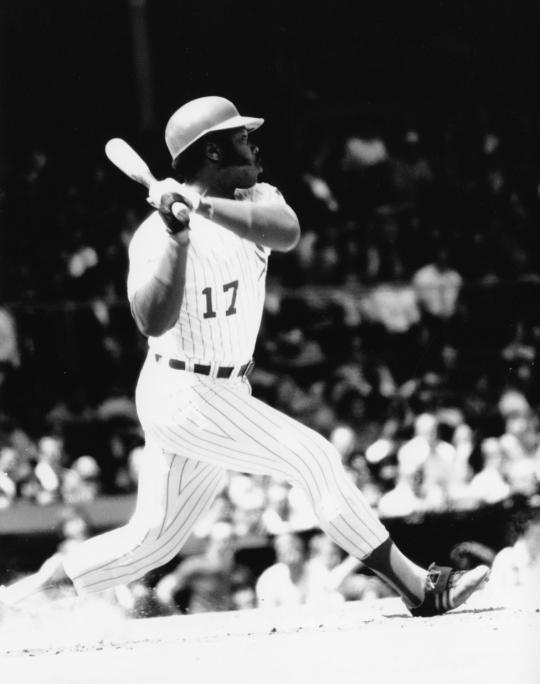

May would put up remarkably good numbers for the season: a .285 average, 79 walks and an OPS of nearly .800. The thumb injury seemed only to affect his power, as he finished with 12 home runs, a falloff from the 18 of his rookie season. In the field, May threw surprisingly well for a man with only nine and a half fingers.

In 1971, the White Sox changed managers, bringing in Chuck Tanner to replace Gutteridge. Tanner decided to move May to first base, where he went through some growing pains defensively but continued to hit with consistency. May would lead the White Sox in batting average (.294) and stolen bases (16).

Then came the breakout season of 1972. Shifted back to left field, May hit .302, compiled an on-base percentage of .405 and posted an OPS of .843. He not only made the American League All-Star team but finished 21st in the MVP voting, as the Sox made a push for first place in the West before finishing runner-up to the Oakland A’s.

The following season, May’s batting average fell to .268, but he also hit with far more power, reaching career highs with 20 home runs and 96 RBIs. The White Sox took advantage of the new DH rule by using May in that slot, while still giving him 70 games in the outfield. Once again, May received some consideration for league MVP.

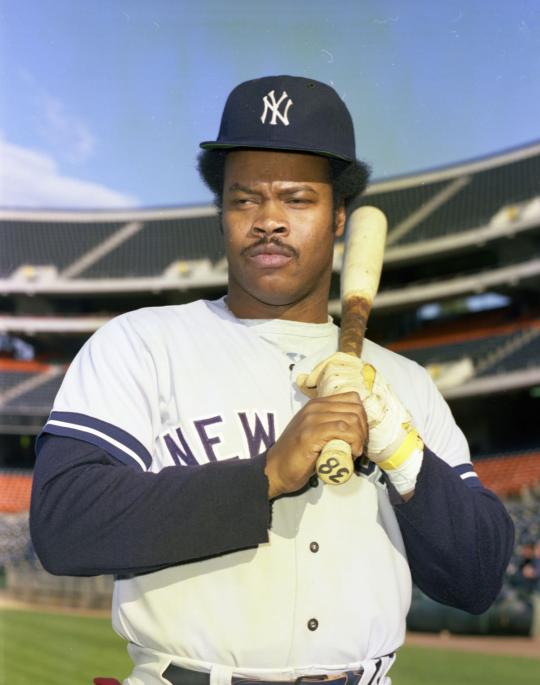

The ’72 and ’73 seasons turned out to be the peak of May’s career. His hitting, both in terms of power and batting average, fell off considerably over the next two and a half seasons, prompting a trade in the middle of 1976. The White Sox sent him to the New York Yankees for veteran left-hander Ken Brett and speedy outfielder Rich Coggins.

May experienced a bit of a renaissance with the Yankees, who used him as a platoon DH. He didn’t hit with much power, but reached base nearly 36 percent of the time. The trade helped May out in another way, as the Yankees won the American League pennant, giving May his first taste of the postseason. Sadly, the season was also marked by tragedy. In July, May’s three-year-old daughter Elizabeth died after a long struggle, having suffered brain damage at birth.

In the spring of 1977, May returned to the Yankees, but muddled through a difficult start to the season. The in-season acquisition of Cliff Johnson also cut into his playing time as a DH. In mid-September, the Yankees decided to discard May, sending him to the California Angels in a cash transaction. The timing would prove cruel, with the Yankees less than a month away from winning a world championship.

Finishing out the season with the Angels as a pinch-hitter and bench player, May batted .333 in 23 plate appearances. He became a free agent at season’s end, and with his options limited in the major leagues, he signed a more lucrative contract to play with the Nankai Hawks of the Japanese Leagues. While many American players of that era struggled to make the transition to the Japanese style of play and culture, May thrived. He played four seasons with the Hawks, putting up excellent numbers in each of his first three years. After a down season in 1981, May decided to retire at the age of 33.

Returning to the states, May joined the U.S. Post Office, working as a mail carrier and clerk for 20 years before returning to the game as a team ambassador for the White Sox. He continues to work for the White Sox to this day, one of the organization’s last links to the 1960s.

It has been a long and admirable career in baseball for Carlos May. It’s a career that could have ended in only its fourth year, thanks to a mishap that nearly resulted in tragedy. Instead, May’s courage and perseverance proved the skeptics were premature in declaring his career over and done with.

Nine and a half fingers, along with a lot of heart, turned out to be more than enough.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum