- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1974-75 Topps Jim Perry

#CardCorner: 1974-75 Topps Jim Perry

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

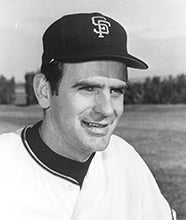

When you say the name “Jim Perry” to me, two people come to mind. One was Jim Perry the broadcaster, the host of a popular 1970s game show called, appropriately enough, Card Sharks. The other is Jim Perry the ballplayer, the perpetually gray-haired right-hander who looked more like a pitching coach than a pitcher.

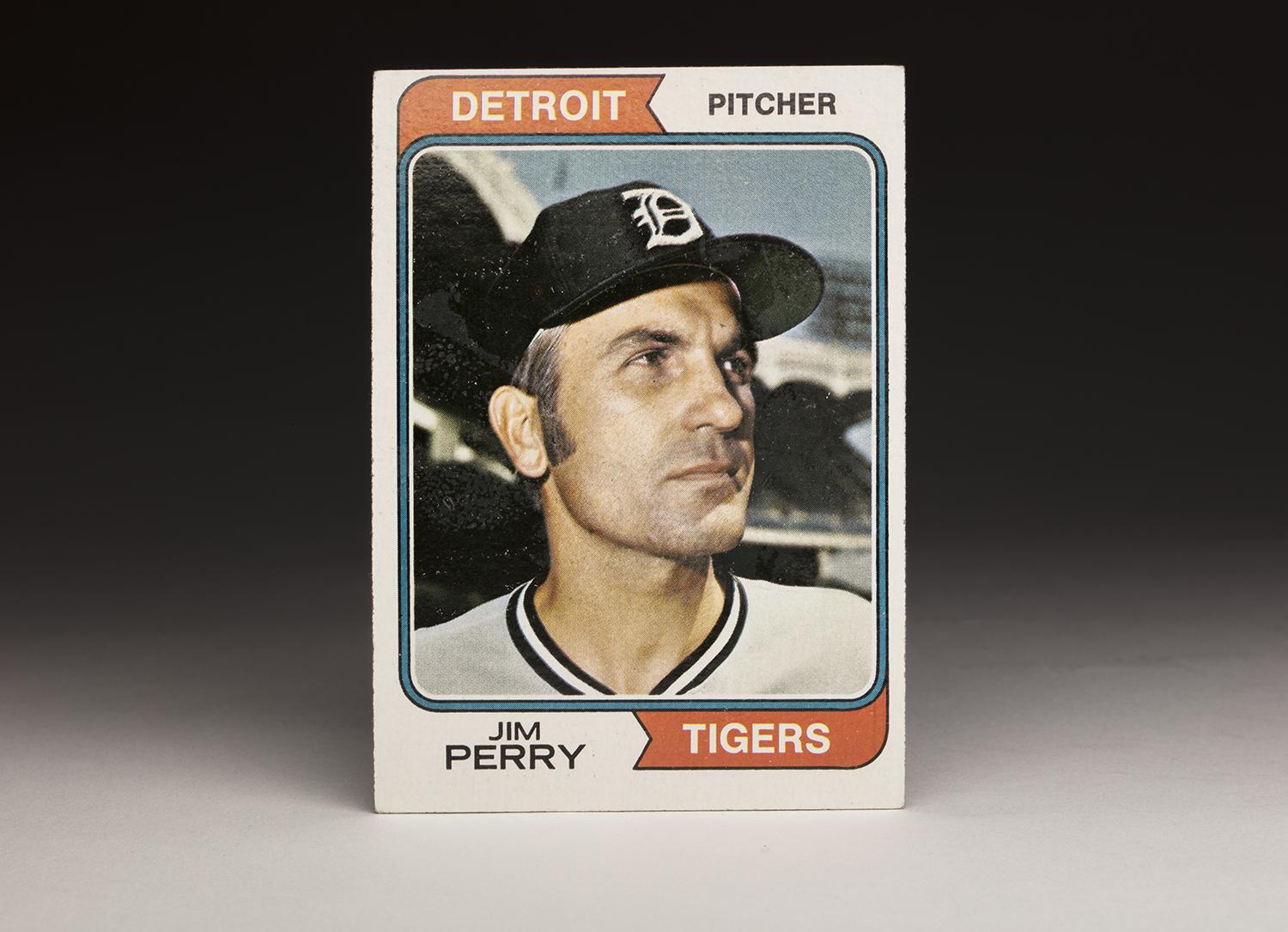

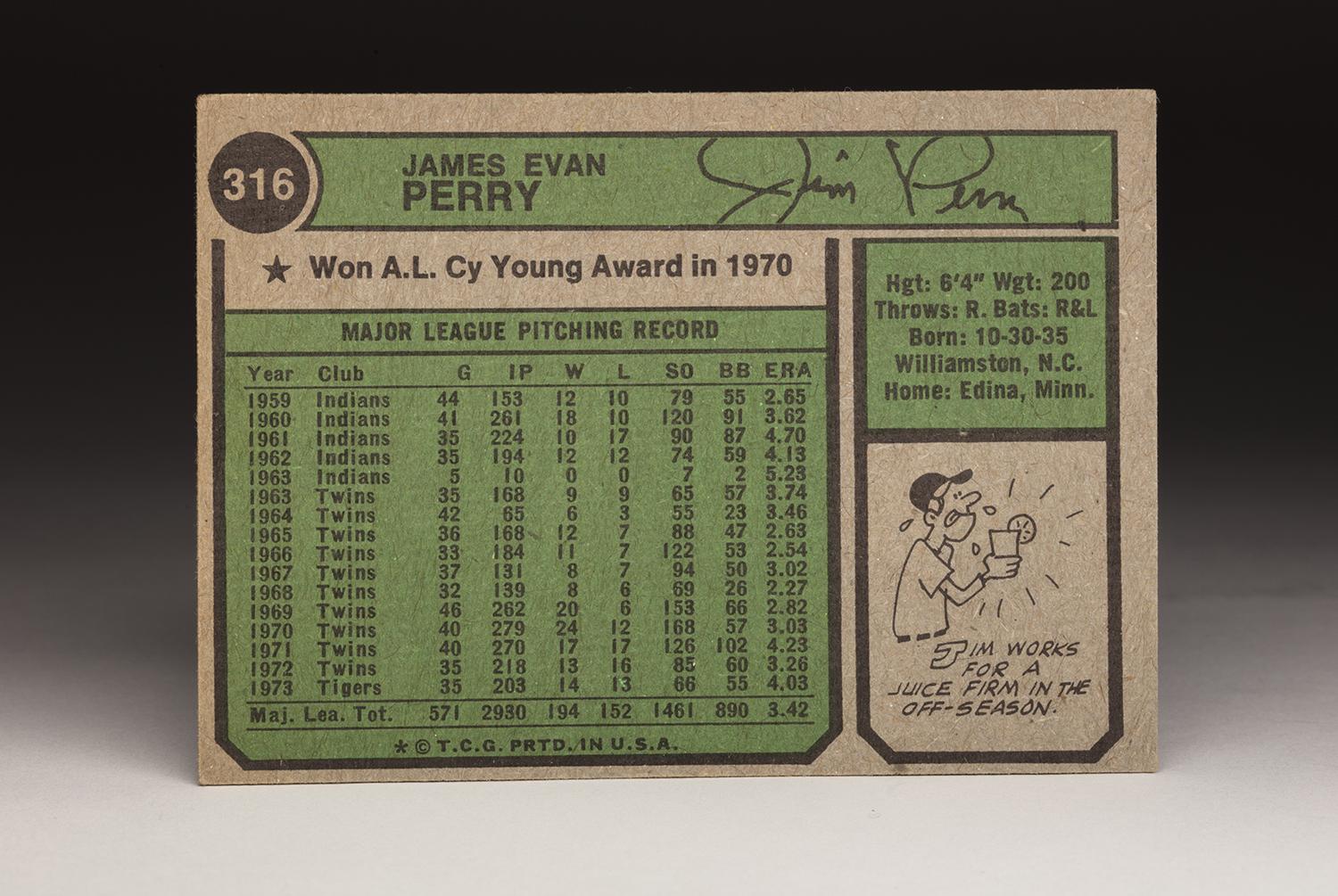

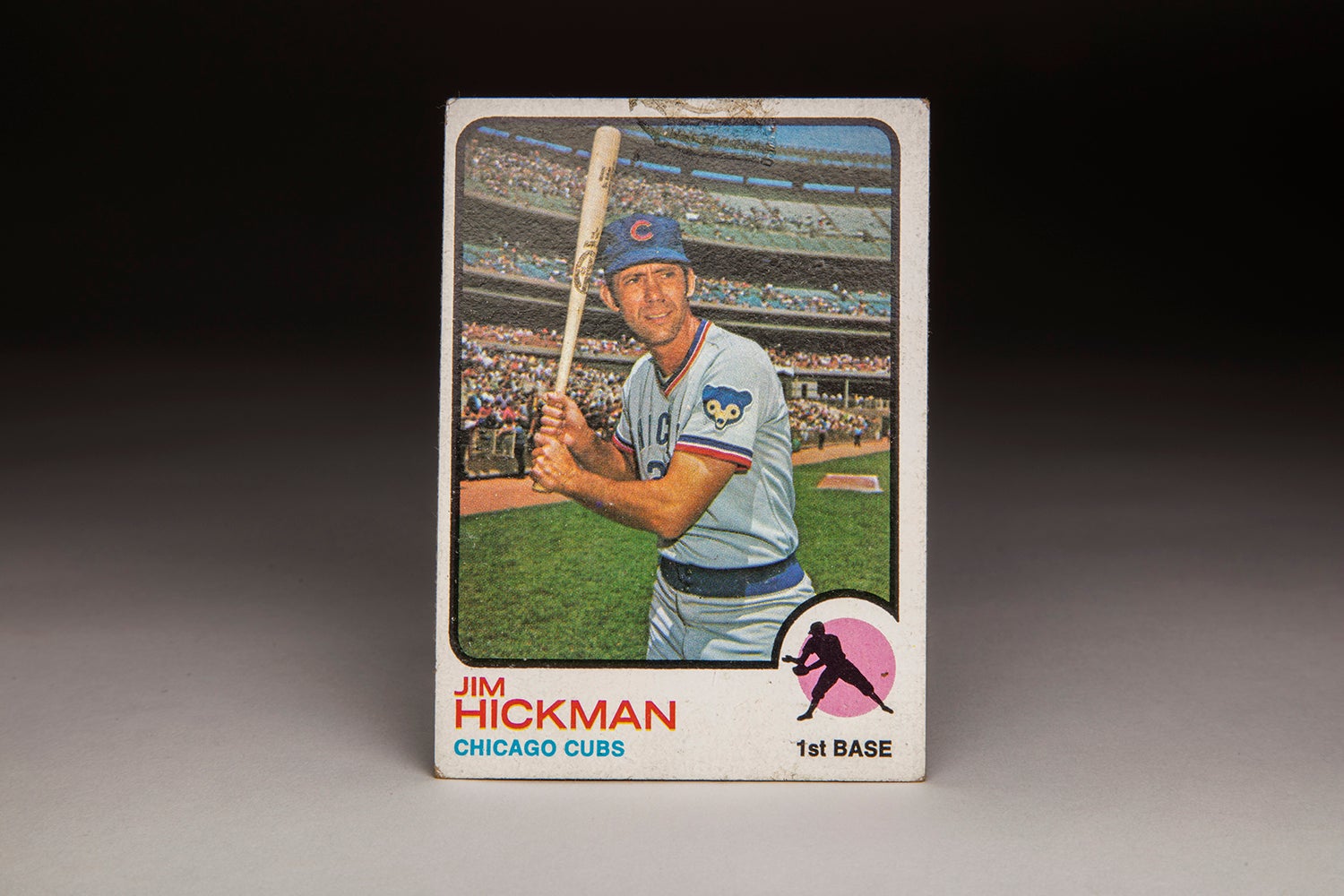

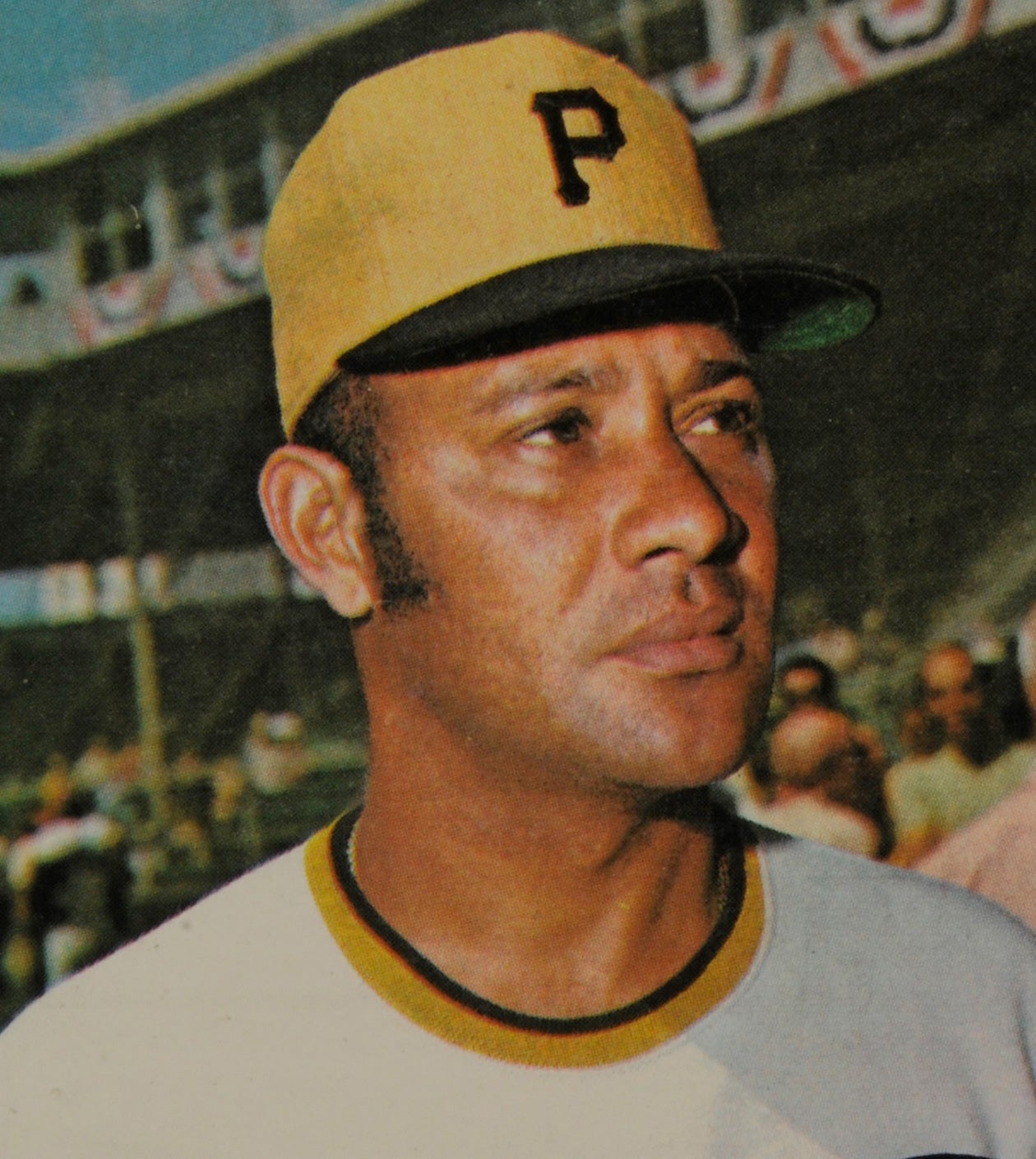

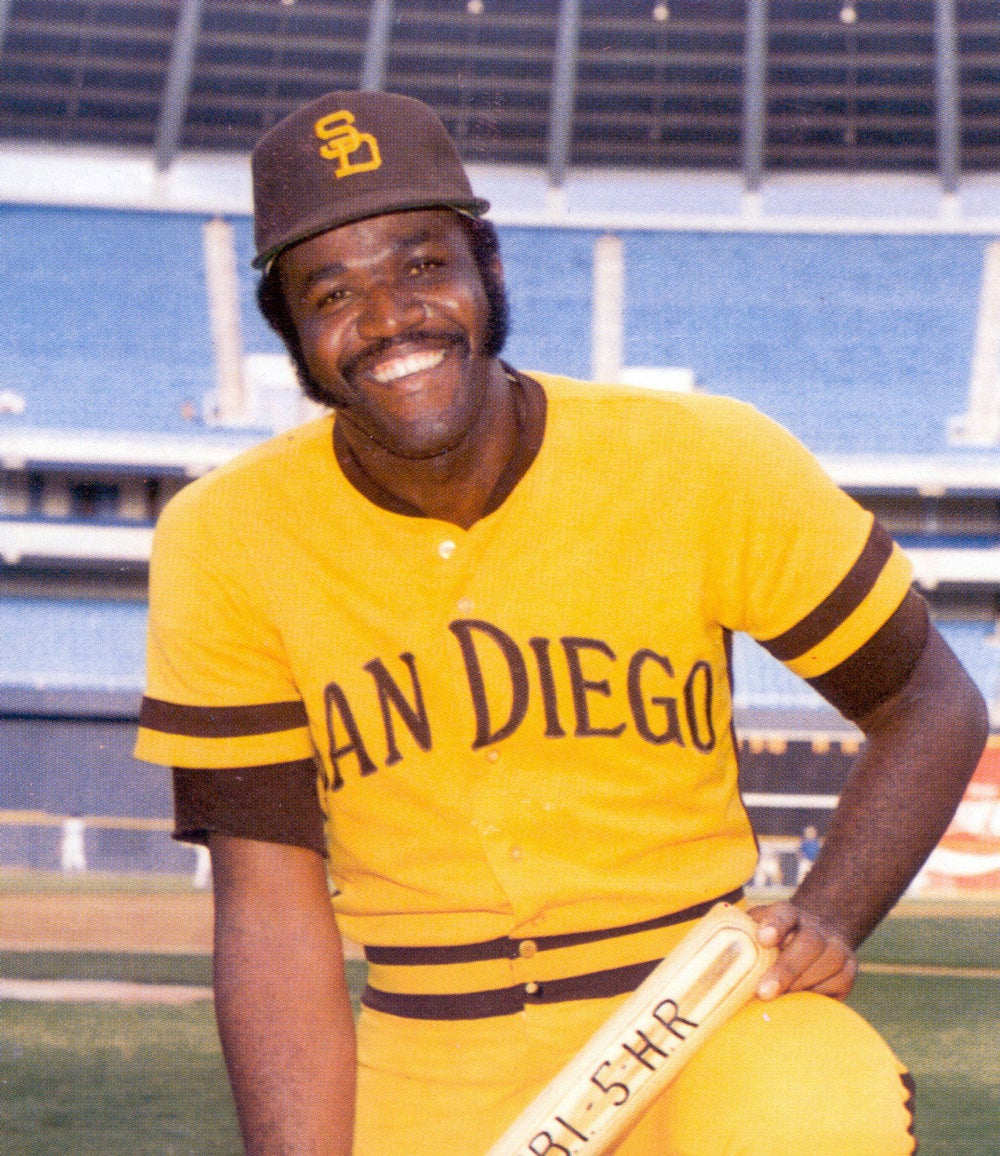

In 1974 and ’75, the Topps Company produced the final two cards of Perry’s career; to say the least, they both look a little bit odd. In each case, we can see rather extreme examples of airbrushing. The 1974 card shows him wearing the colors of the Detroit Tigers, which have been airbrushed over his previous colors with the Minnesota Twins. The Tigers’ logo on Perry’s cap is unusually large, a sure sign that it is not authentic.

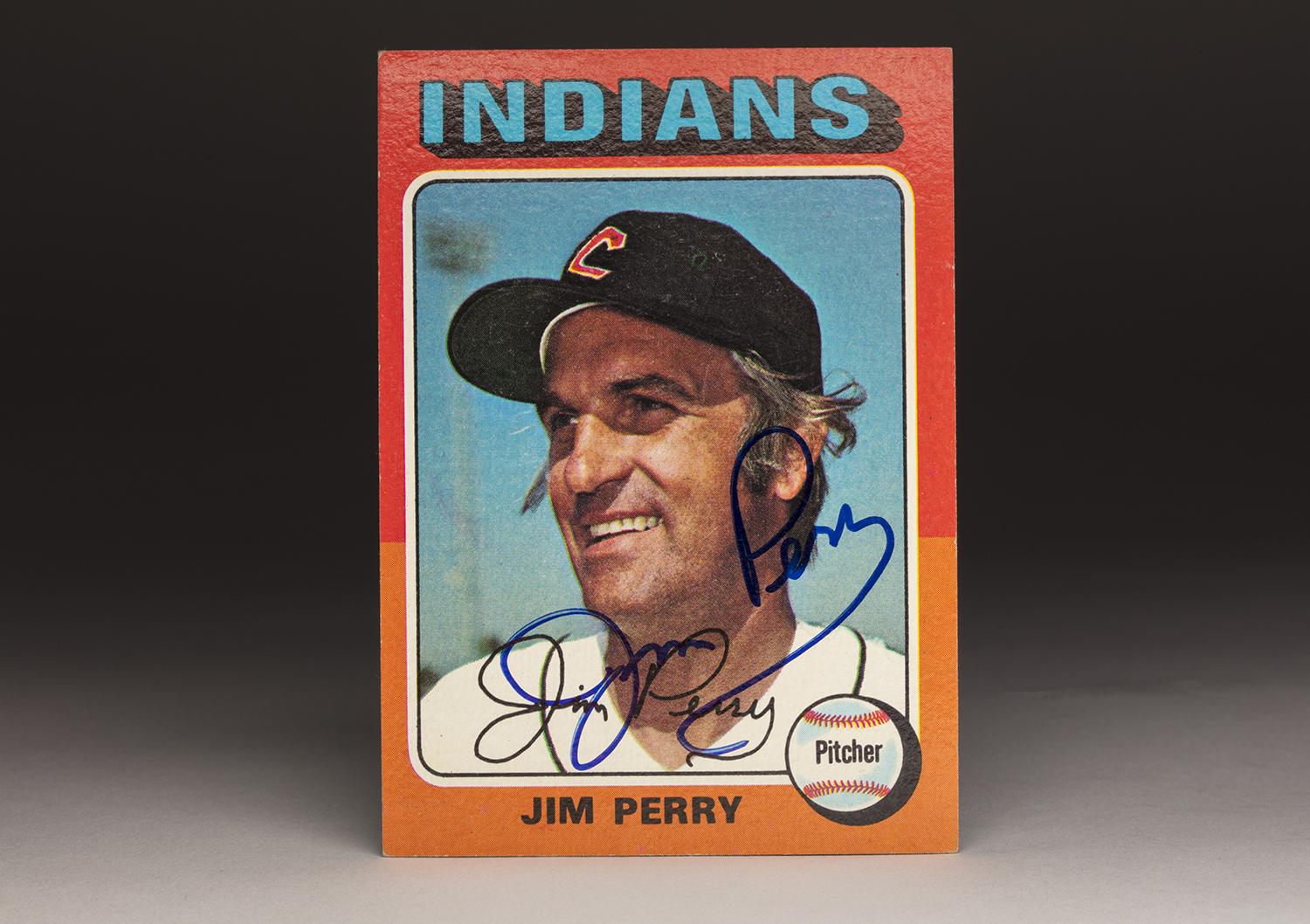

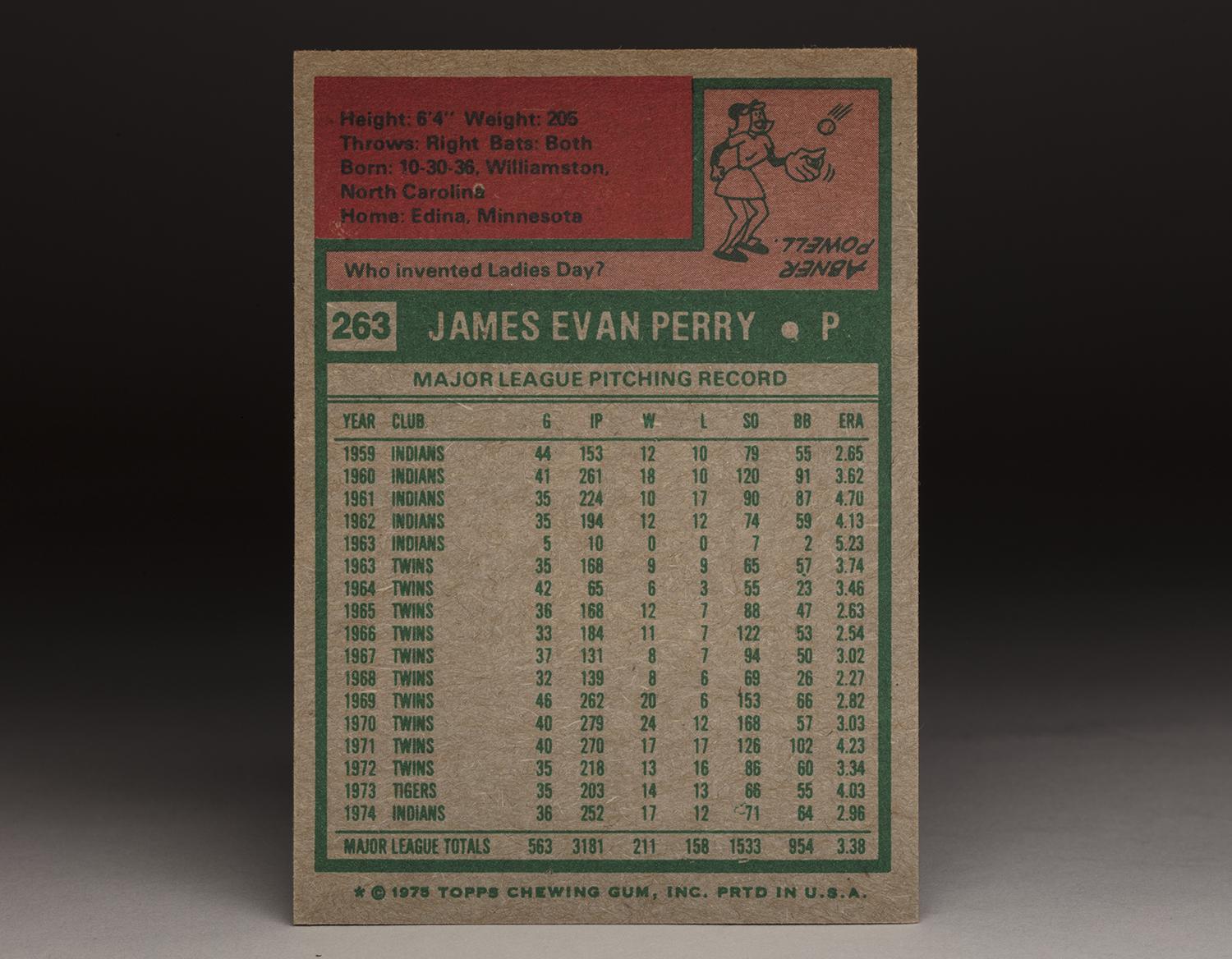

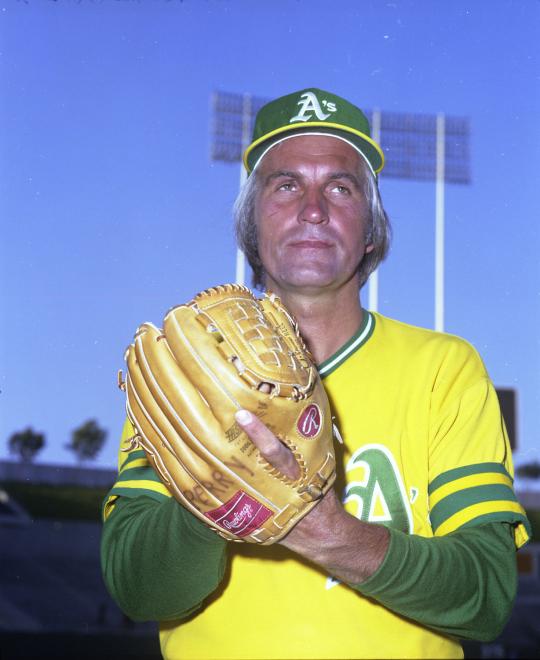

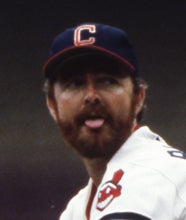

In 1975, Topps decided to airbrush the colors of the Cleveland Indians over the original photograph, which appears to feature a Tigers uniform (at least based on what we can see at the top of the jersey). By the time the 1975 card came out, even the airbrushing was out of date, if only because Perry had moved on from the Indians, where he had struggled badly. By now, Perry was pitching for the Oakland A’s, where he appeared in 15 games before drawing his release in August.

As a result of all this movement, Perry never appeared on a baseball card as a member of the A’s. Such a card simply doesn’t exist. As a matter of fact, there are very few color photographs that show Perry wearing the green and gold colors of the A’s. For those fans who collect baseball-themed photography, those shots have become elusive, hotly desired by collectors but hard to come by. In fact, only five color photographs of Perry wearing the Oakland colors are believed to exist – and all five are part of the collection at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

One of the country’s leading collectors of baseball photographs and cards is Keith Olbermann, now a broadcaster for ESPN Radio and GQ.com and a lifelong fan of the game. In a recent interview with the Hall of Fame, Olbermann lamented the lack of quality-looking cards for Perry in his later years.

“In his last three seasons, he was traded three times,” Olbermann said. “So his 1973 card shows him with the Twins, who traded him just as the card was coming out in packs. His 1974 card shows him in Twins gear badly airbrushed to look like a Tigers cap and uniform. His ‘75 card shows him in Tigers gear airbrushed to look like a Cleveland cap and uniform – and by May the card was outdated anyway. So an unretouched, new picture of Perry from 1975 is on top of everything else, a relief!”

The “relief” is supplied by Doug McWilliams, who took all five color photographs of Perry as a member of the A’s. That is the same Doug McWilliams who was the longtime photographer for Topps, a veteran of working Spring Training and regular season games for the company from 1971 to 1995. After his retirement, McWilliams donated thousands of his photo negatives to the Hall’s collection, where they are preserved in the Hall of Fame Library.

McWilliams’ rare photographs of Perry are among the most treasured by baseball fans who collect photographs of 1970s vintage.

“Jim Perry, during his swan song with the ‘75 A’s, may not be the Moby Dick of those hunting these images,” Olbermann said, “but he’s at least a very big white whale. There just aren’t any known color shots of him with Oakland. Topps, which makes a nice income selling off its old negatives, didn’t have one. I’ve seen Jim Perry’s Topps photo file and there were no images of him with the A’s or anybody else. He’s even nearly impossible to find in black-and-white.

“So an A’s image of Perry – and taken by Doug, who after all was the Topps photographer in the Bay Area and whose work is impeccable – will lead to a lot of crossing-offs on a lot of dream want lists out there.”

McWilliams’ dream shots of Perry would have become more widespread if only the veteran right-hander’s career had continued. The McWilliams photos were supposed to become the basis for Perry’s 1976 Topps card, if that card had ever come to pass. But Oakland decided to release Perry in August of 1975, thus negating a need for a 1976 card. “There’s no evidence Doug ever sent Topps any Perry photo he shot,” Olbermann explained to the Hall of Fame. “As I understand it, the images he shot for Topps went directly to them as negatives. He shot an entirely separate archive’s worth of images for himself, presumably on a second camera.

“So that’s why Perry had never been seen before in color in an A’s uniform. He was presumably off the Oakland roster by the time Doug was ready to send Topps their negatives of him.”

Once released by the A’s, Perry would never again pitch in the major leagues, officially ending a career that had begun 17 seasons earlier.

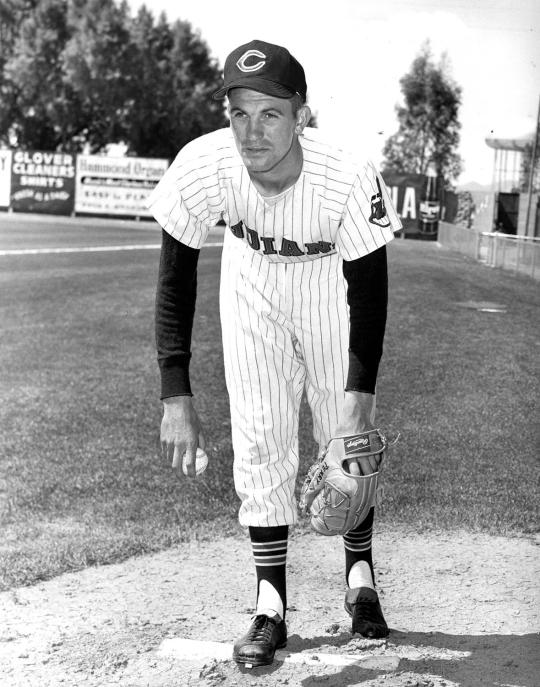

Perry’s long and winding road to Oakland started in 1959, when the Indians brought him to the big leagues for the first time. They had signed the tall, angular right-hander in 1956, and then watched him progress neatly through their farm system. Indians manager Joe Gordon decided to use Perry in a variety of roles, mostly out of the bullpen, but occasionally as a starter. Perry did well, posting an ERA of 2.65, winning 12 games, and saving four others.

The Indians saw enough from Perry to make him a fulltime starter in 1960, even after the midseason trade of Gordon to the Tigers in exchange for Detroit manager Jimmy Dykes. Emerging as a workhorse who logged 261 innings, Perry led the American League with both 36 starts and 18 wins, including four shutouts. Thanks to those numbers, Perry received some support in the MVP voting, an award that traditionally has been steered toward position players.

In 1961, Perry made the All-Star team, but he tired in the second half, perhaps because of the previous year’s workload. His ERA rose to 4.71, while his strikeout total fell from 120 to 90. Perry’s pitching remained spotty in 1962, but his game collapsed early in 1963, prompting a trade by the Indians’ always aggressive general manager, Frank “Trader” Lane. Early that season, Lane traded Perry to the Minnesota Twins for a journeyman left-hander named Jack Kralick. The trade would never become as well remembered as the Indians’ ill-fated decision to trade Rocky Colavito for Harvey Kuenn, but it would rank as one of the poorest deals in the franchise’s long history.

That is not to say that Perry became an overnight sensation in the Twin Cities. He struggled, as he continued to move between the bullpen and the rotation. He was labeled as “too nice” by some, a rather silly criticism that had little to do with his pitching skills. Always quiet, Perry didn’t drink or smoke, remaining the model citizen. Whatever the reason, Twins manager Sam Mele did not take a liking to Perry, whom he made a fulltime reliever. Perry struggled in both 1963 and ’64, pitching the latter season exclusively out of the bullpen. It seemed like a waste of Perry’s talents.

An important change came for Perry – and the rest of the Twins’ pitching staff – in 1965. The legendary Johnny Sain entered the scene as the Twins’ pitching coach. Sain worked with Perry on two specific measures. One involved the addition of a curve ball, one that broke sharply. The other involved the decision to “turn over” his fastball, so that it would run in on the hands of right-handed batters.

Perry made both adjustments perfectly. With injuries to Jim “Mudcat” Grant, Dave Boswell and Camilo Pascual, Perry stepped up as a staff saver. He became the temporary ace of the staff, pushing the Twins into first place. He also drew the praise of Sain. “I’ve never seen a man work so hard on his own,” Sain told the Sporting News. “The coaches and manager have been getting the credit for the team leading the league, but it’s effort like Perry’s that put us there.”

Filling the bill while the other starters recuperated, Perry catapulted the surprising Twins to the American League pennant. Grant and Jim Kaat soaked up most of the starts during the World Series, but Perry returned to the bullpen without complaint, pitching creditably as the Twins lost the series in seven games to the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Perry continued to pitch well over the next three seasons, drawing praise for his toughness and his willingness to take the ball in any situation. But he continued to split his time between starting and relieving, a job that he that assumed reluctantly and one that prevented him from compiling impressive win totals. That all changed in 1969, when the Twins hired Billy Martin as their manager. Martin liked Perry and made him a fulltime member of the starting rotation. By season’s end, Perry had become the staff ace, winning 20 games and posting an impressive ERA of 2.82.

Even after Martin’s firing at the end of the 1969 season, “Slim Jim” remained in the rotation. In fact, he made 40 starts in 1970, leading all American League pitchers. Perry also won a league-high 24 games, all while pitching 278 innings. After the season, AL beat writers rewarded Perry by naming him the winner of the Cy Young Award. Perry had reached his peak, even though he was now 34 years old.

Perry put in two more seasons with the Twins, pitching solidly but not at the level of what he had done in 1969 and ’70. Concerned that the end might be near, the Twins traded him to the Tigers for a young right-hander named Dan Fife. That allowed Perry to reunite with Martin, now the manager of the Tigers.

Perry pitched creditably for the Tigers, winning 14 games and logging 203 innings. But he lost an ally late in the season, when the Tigers fired Martin and replaced him with coach Joe Schultz. Without Martin in his corner, the Tigers traded Perry, sending him to the Indians as part of a three-way trade that also involved the New York Yankees.

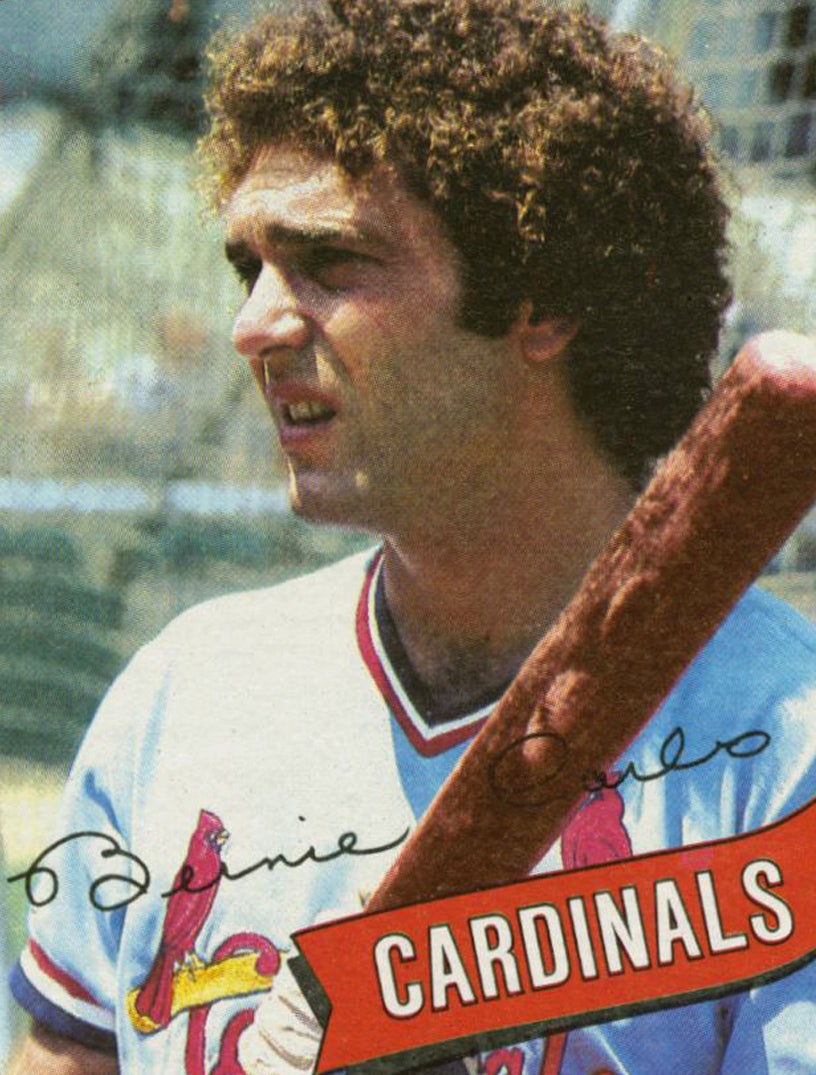

The trade gave Perry the chance to play on the same team as his famous brother, Gaylord Perry. While he might have been overshadowed by his Hall of Fame brother, Jim loved the experience of playing with his brother. “It was great,” Jim told me during a visit to Cooperstown in 2011. “We had our families up there in Cleveland. Our families finally got to know each other, because all those years we were separated. He was in the National League and I was in the American League. We had a great time, we ate together, we went to the ballpark together. That was great.”

Perhaps rejuvenated by the reunion with Gaylord, Jim enjoyed a bounceback season in ‘74, winning 17 games and forging an ERA of 2.96. The brothers Perry formed one of the most effective pitching tandems in the league.

In 1975, Perry showed the first real decline in his pitching. He started the season poorly, losing six of his first seven decisions. There was also clubhouse tension on the Indians, making for a difficult atmosphere that seemed to take a toll on Perry. On May 20, the Indians decided to shake up their pitching staff, sending Perry and veteran righty Dick Bosman to the A’s for Blue Moon Odom.

Jim Perry began his 17-year long baseball career with the Cleveland Indians in 1959. He would play for the Indians from 1959-1963, and return again in 1974. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

The A’s gave Perry a look that included 11 starts and four relief appearances, including a complete game one-hitter, but it was clear that his prime pitching days were over. A’s owner Charlie Finley released him in August, ending a career that could best be described as workmanlike – and underrated.

Since his retirement, Perry has done some scouting work for the A’s, but has mostly remained out of the baseball spotlight, preferring a quiet life working on his farms. I finally had the chance to meet Perry in Cooperstown in 2011, when he attended the induction of his longtime Twins teammate Bert Blyleven. He impressed me as a humble man, but one who also took pride in his durability.

“What I’m really proud of, I was a short man, a middle man, a starter, and was never on the disabled list,” Perry said during his visit to Cooperstown. “When I was asked to pitch, I pitched – every four days. In 17 years, I was never on the disabled list. Not too many guys can say that.”

Additionally, not too many players can say that their photos have become elusive collector’s items. Rare photos of the underrated Jim Perry, wearing the green and gold of Charlie Finley’s A’s, are something that the Hall of Fame can call its own.

Special thanks to Keith Olbermann for his help in assembling this article.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame