- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1974 Topps Gary Matthews

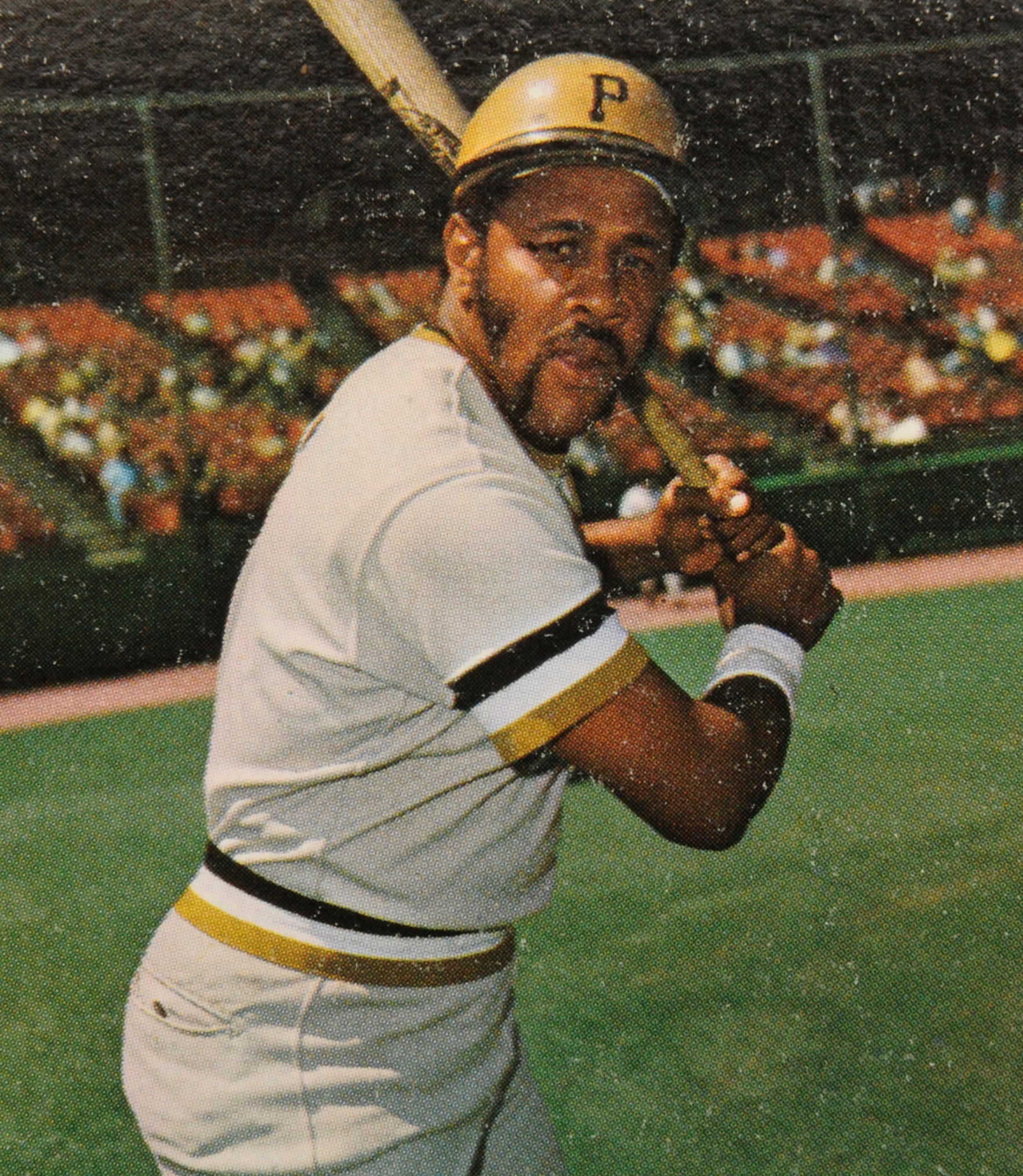

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Gary Matthews

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

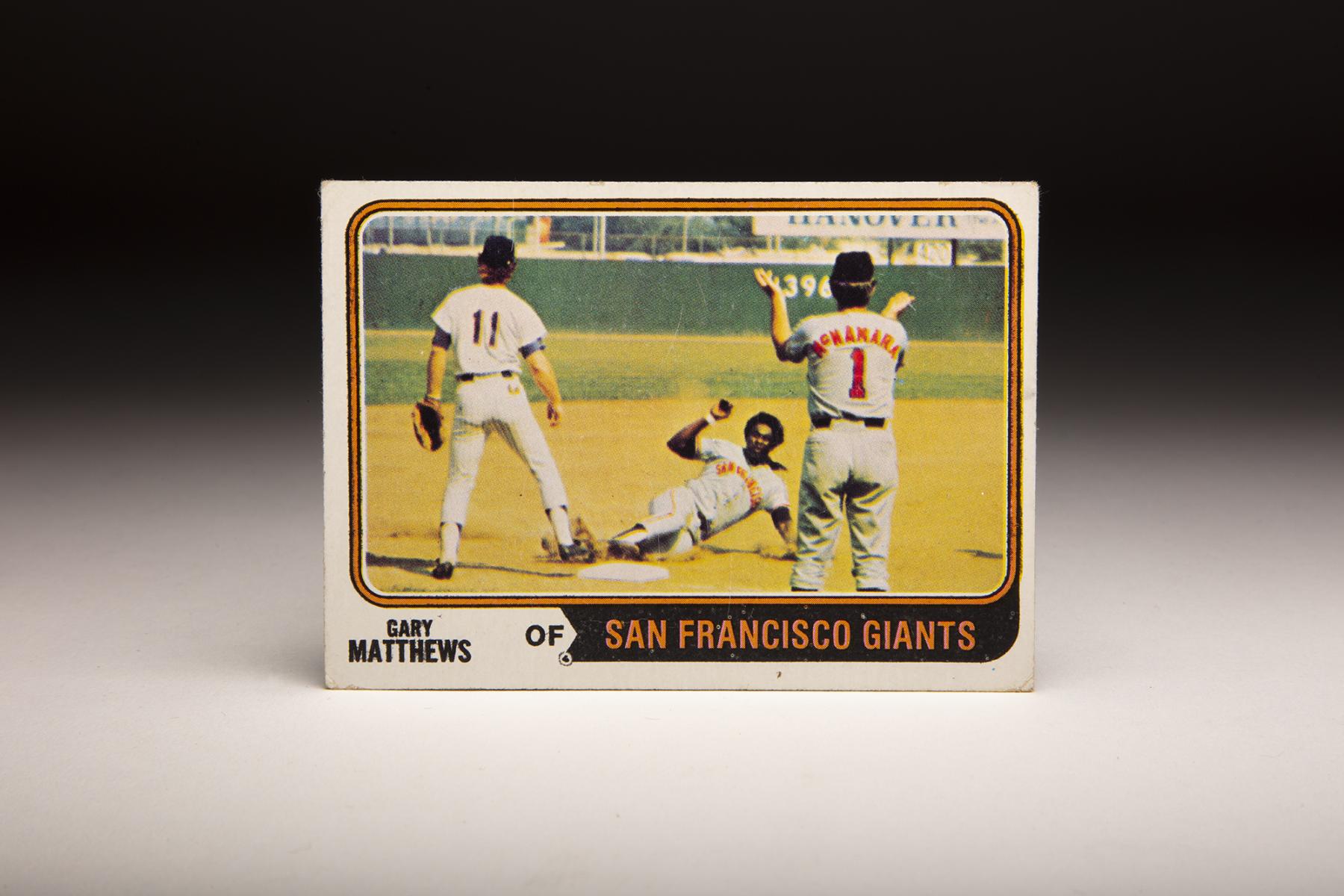

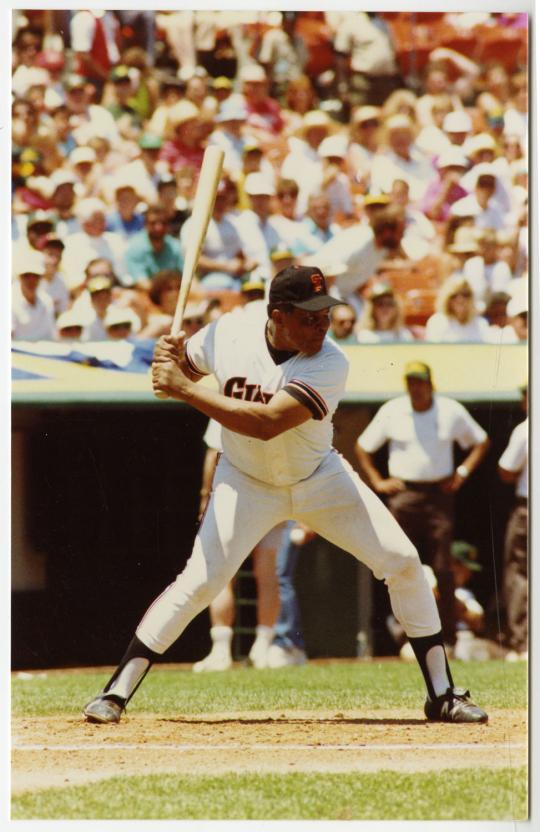

There’s a certain symmetry to Gary Matthews’ 1974 Topps card.

On the far left is New York Mets third baseman Wayne Garrett, who is awaiting a throw that will never come. (Even if it does, it will be too late.)

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

On the far right, we see San Francisco Giants third base coach John McNamara, who is holding his hands outstretched with his palms up, an indication that he wants his base runner to come in standing. And in between McNamara and Garrett is the card’s featured player, Matthews himself, who has chosen to ignore his coach’s suggestion of a standup arrival. Always hustling, always wanting to be sure, the ever aggressive Matthews gives us a look at his textbook feet-first slide into the bag.

The landscape (or horizontal) nature of the card allows us a clear view of all three characters; Garrett and McNamara have their backs turned to us, while Matthews is seen from the front, his right arm extended in mid-air and his left arm braced against the ground. It’s simply a great shot.

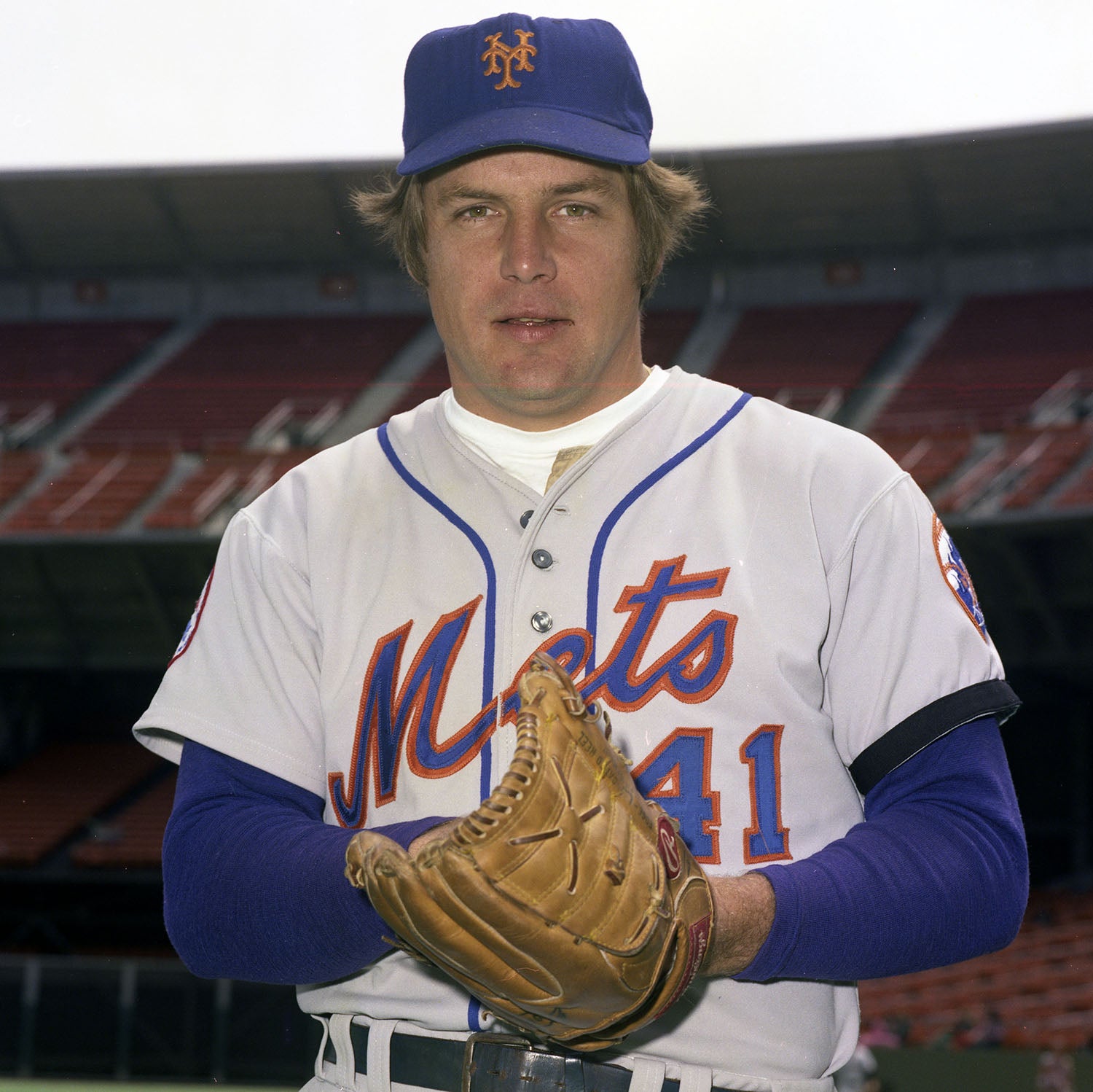

The landscape cards are perhaps the best ones in the 1974 Topps set, not only because they allow for the inclusion of multiple players and coaches, but because they give us a panoramic view of the ballpark. While the vertically-oriented cards are better suited to profiles and posed shots, the landscapes are much better at portraying full-bore action. We see this with the Matthews card, and with other cards for players like Steve Garvey, Tom Seaver, Mike Epstein and Vada Pinson.

The Matthews card also gives us an opportunity to do some “sleuthing” – in other words, a search to find the date and place of the game action in question. In this case, the place is easy – it’s Shea Stadium, home of the Mets. We see that Garrett is wearing the Mets’ home uniform, and if that’s not enough, the green fencing, the 396-foot marker in the outfield, and the Manufacturers Hanover Bank sign in the background are all giveaways that this is old Shea.

Finding the date of the game, at least in this case, is not very difficult, either. Assuming that the game was played during the 1973 season, we find that the Mets and Giants played only two day games at Shea Stadium. They occurred on back-to-back days, Aug. 25th and 26th. We can eliminate the game of the 26th, since Garrett did not play third base that day. That leaves us with the game of Saturday, Aug. 25th. Both Matthews and Garrett played that day, with Matthews reaching base twice via hits.

In the top of the fifth inning, Matthews stepped in against Tom Seaver, delivering a two-out single to left field. Up came Tito Fuentes, who followed with a single of his own to left field.

That hit advanced Matthews to third, with that moment captured by Topps. But Matthews was left stranded, as Seaver retired Bobby Bonds on a fly ball to center field.

Just for fun, let’s fill in some other gaps from that game. The Giants, behind the shutout pitching of Tom Bradley, beat Seaver, 1-0. Seaver was one of three Hall of Famers to appear in the game.

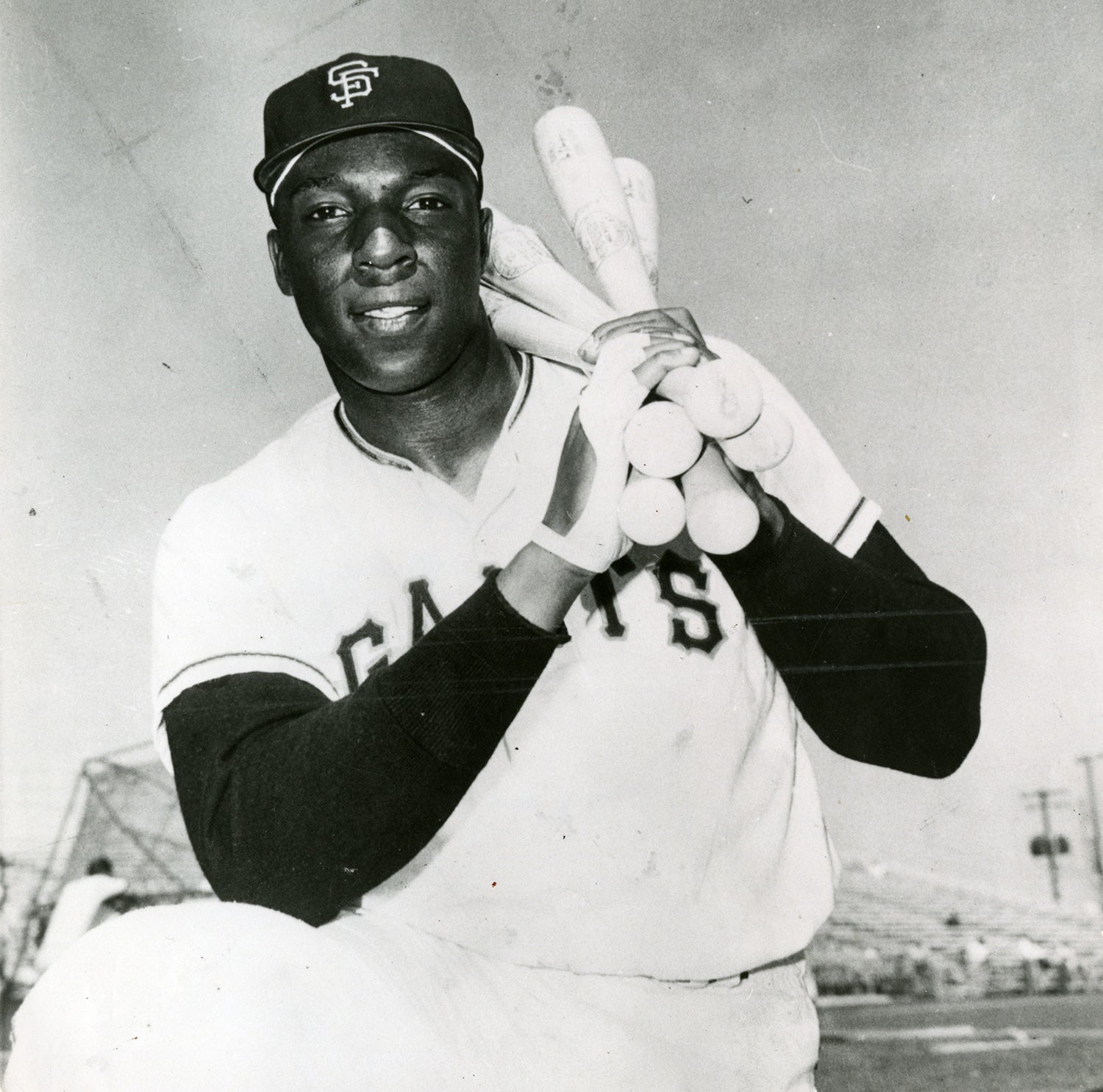

The others were Willie Mays, who pinch-hit for the Mets and played center field, and Willie McCovey, who played most of the game at first base for the Giants before being lifted for pinch-runner Gary Thomasson.

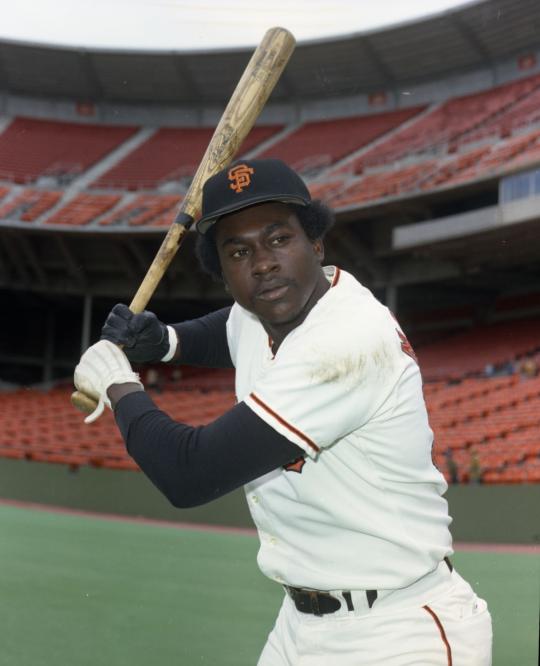

In that game, Matthews batted leadoff for the Giants. That’s not how I remember him, but that is the role that he filled for the Giants in his early major league days. Matthews was the kind of player who could bat just about anywhere in the lineup. He drew enough walks to bat leadoff or second, and batted with sufficient power to bat third, fourth or fifth.

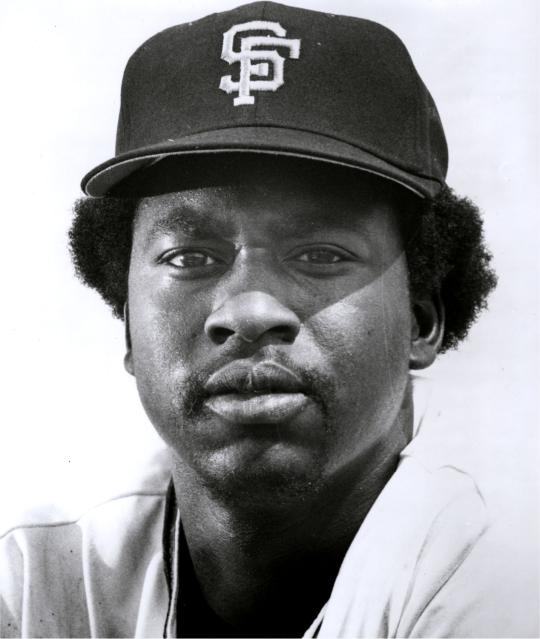

Not surprisingly, Matthews was a highly touted player coming out of San Fernando High School in California. In 1968, the Giants made him their first-round draft choice. Already rich in outfielders, the Giants viewed Matthews as a possible successor to Mays and someone who would join Bonds in forming a dynamic outfield of the future.

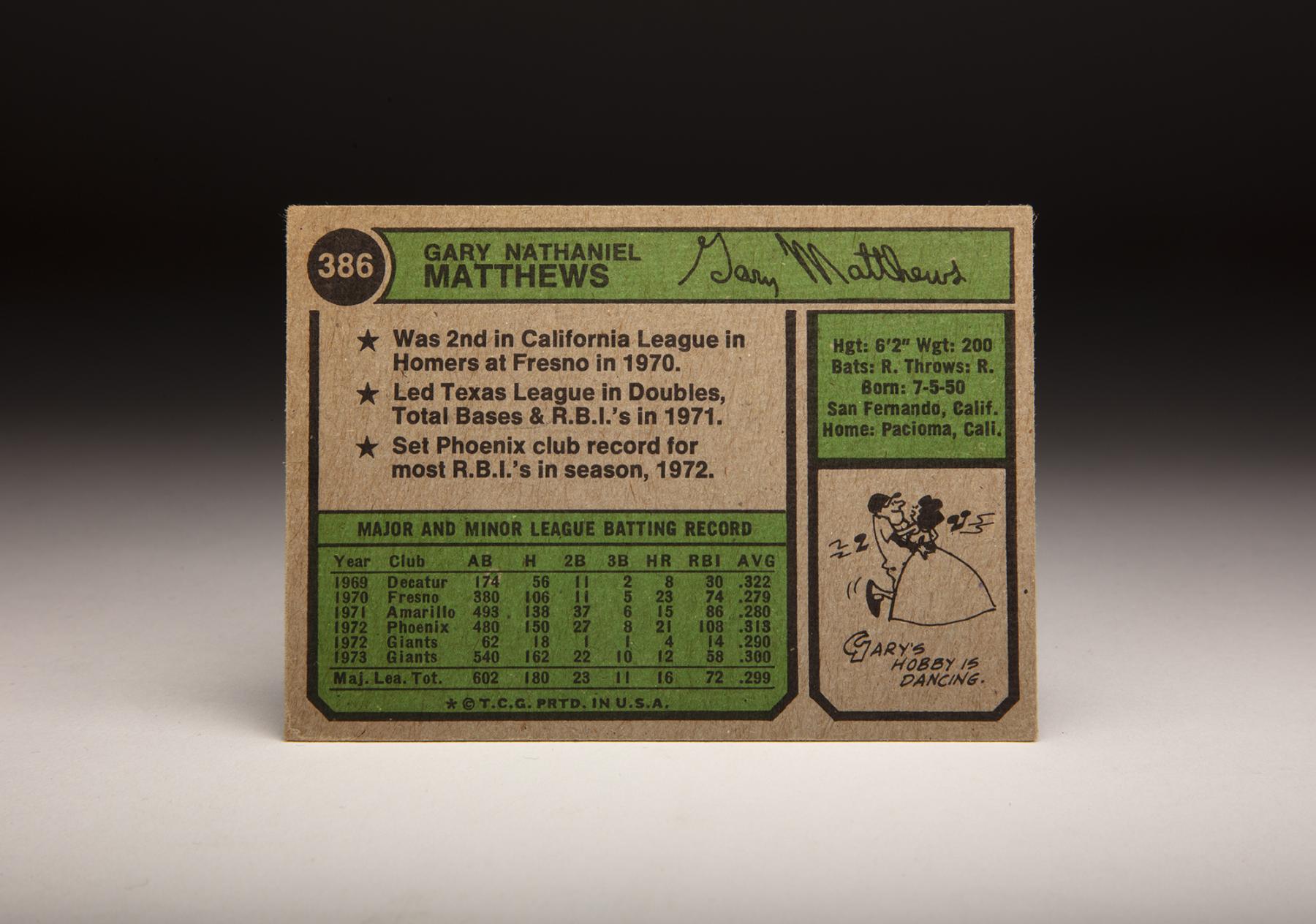

Matthews moved up steadily through the San Francisco system. In 1969, he debuted in the Class A Midwest League, and then advanced to the California League in 1970. The following season, he earned a promotion to Double-A. And then in 1972, he made a solid transition to Triple-A Phoenix. At every stop, Matthews hit for average and power.

By the middle of the ’72 season, it was evident that Matthews was ready to face major league pitching. After the Triple-A season came to an end, the Giants promoted him to San Francisco. Still only 22 years old, he played in 20 late-season games and more than held his own, batting .290 with four home runs.

With Mays now gone – having been traded to the Mets – and Bonds and Garry Maddox entrenched in right and center field, respectively, the Giants had room in left field. They put Matthews in their 1973 lineup and watched him hit an even .300 with 12 home runs and 17 stolen bases. Those numbers earned him National League Rookie of the Year honors.

Clearly, Matthews could do it all: Hit with power, steal bases, and make spectacular plays in left field, even if at times his defensive play could be erratic. Matthews also played with a level of passion and aggressiveness rarely seen. He excelled at taking the extra base against outfielders with poor arms and earned a reputation for one of the hardest takeout slides in the National League, much to the chagrin of opposing middle infielders.

Given his talent and attitude, the Giants felt that Matthews would become a superstar, a player with the potential of a Bonds. In actuality, Matthews would continue to produce at a high level, but would not quite take the next step to stardom. Over the next three seasons, he would fall short of a .300 batting average and would reach a high of only 20 home runs. His home ballpark did not help matters. Candlestick Park, with its tricky winds and cold temperatures, would make life difficult for most of the Giants hitters during the 1970s.

In 1975, the Giants moved Matthews out of the leadoff spot and made him their cleanup hitter, but a broken thumb interfered with his season, limiting him to 116 games. One year later, Matthews and the Giants found themselves in the middle of a contract dispute. Matthews wanted a multiyear contract, but Giants owner Bob Lurie was unwilling to meet his demands. So Matthews played under the terms of a one-year contract. The Giants’ failure to secure Matthews to a longer contract would soon lead to a departure.

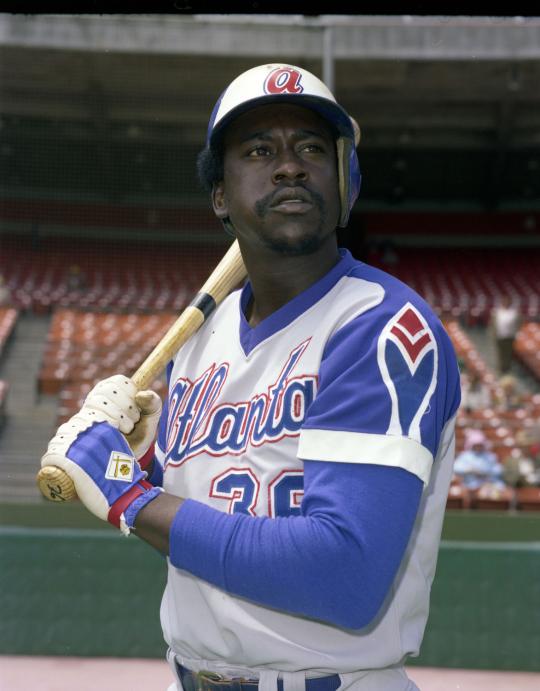

Baseball’s newly created system of free agency allowed Matthews to hit the open market after the 1976 season. But before the season came to an end, a representative of the Atlanta Braves’ front office contacted Matthews about his interest in playing for them. The Giants filed a tampering charge against the Braves; Commissioner Bowie Kuhn agreed with the Giants, ruling in their favor. The Commissioner ruled that the Braves would have to sacrifice their first-round pick in the upcoming January draft and pay Major League Baseball a fine of $10,000.

Kuhn’s ruling did not prevent the Braves from pursuing Matthews as a free agent once the season ended. Only 25 years of age, Mathews received offers from the Braves and several other teams. Spurred on by their free-spending owner, Ted Turner, the Braves won the bidding war. Matthews signed a five-year deal worth $1.2 million, a blockbuster contract for the era of the 1970s. As a bonus, the Braves agreed to give Matthews a new car for every year of the contract.

As he did for San Francisco, Mathews became the Braves’ starting left fielder. He hit well, compiling an OPS of just under .800, but his performance couldn’t prevent the Braves from losing 101 games.

In 1978, the Braves switched Matthews from left field to right field, flip-flopping him with Jeff Burroughs, who did not throw or run nearly as well as Matthews. Making the adjustment to the new position with ease, Matthews put up even better offensive numbers in 1978, but injuries limited him to 129 games. And then in 1979, he assembled a career-best season: 27 home runs, a .304 batting average, and an OPS of .865. For the first time, Mathews made the All-Star team.

Matthews’ style of play won over the fans in Atlanta. Forever hustling and persistently trying to take advantage of an opponent’s mistake, Matthews did his best to justify his high salary.

“When you’re paid well,” Matthews told sportswriter Earnest Reese, “you owe it to your teammates and the fans to give it all you’ve got.” For Mathews, full effort made the game more enjoyable. “It’s really a case of having fun – especially if you love the game.”

As well as Matthews played in 1979, he could not match that high standard of production in 1980. The falloff turned him into trade bait – though not right away. The Braves waited until Spring Training of 1981; looking for pitching, the Braves dealt Matthews to the Philadelphia Phillies for right-hander Bob Walk.

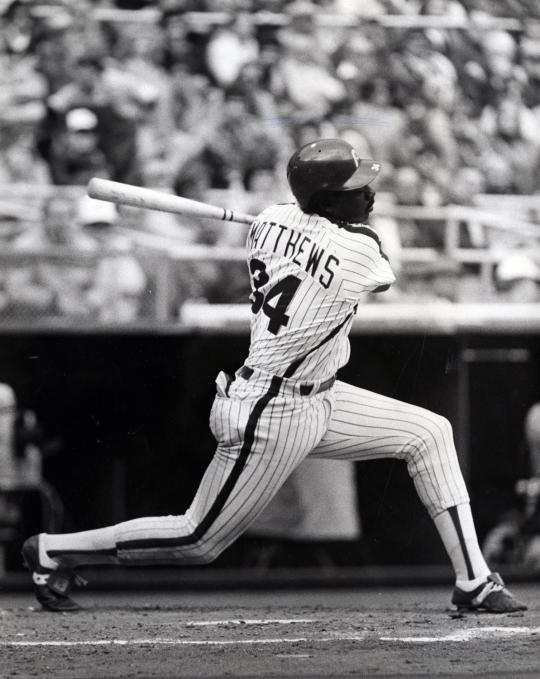

Thanks to the trade, Matthews was leaving the fourth-place Braves and joining the defending world champions. The Phillies suffered a letdown in 1981, but Matthews was hardly at fault. He batted .301 during the strike-shortened season and finished 13th in the MVP voting. Posting another fine year in 1982, Matthews again received support in the MVP balloting.

It was during his tenure with the Phillies that Matthews earned his famed nickname, “Sarge.” It originated with one of his teammates, Pete Rose, another player known for all-out hustle at all times, regardless of the situation.

Rose admired Matthews’ ceaseless effort and work ethic, and his willingness to take a leadership role in the Phillies’ clubhouse. And, thus, Sarge was born.

After the success of 1981 and ’82, Matthews struggled and hit with little power in 1983, but the Phillies won the National League East title, giving the veteran outfielder his first shot at postseason play.

Matthews put up a Ruthian effort in his postseason debut, hitting three home runs and batting .429 to lead the Phils to a four-game NLCS victory over Los Angeles. For his efforts, Matthews earned the series MVP Award.

Matthews would hit another home run in the World Series, but the Phillies lost in five games to the Baltimore Orioles. Those games would turn out to be his swansong with Philadelphia. The following spring, the Phillies acquired outfielder Glenn Wilson in a Spring Training trade. With the addition of Wilson, the Phillies now had 10 outfielders on their 40-man roster. Given the glut, someone had to go – and it would be the aging Matthews. Three days after the acquisition of Wilson, the Phillies traded Matthews, fellow outfielder Bob Dernier and pitcher Porfi Altamirano to the Chicago Cubs for veteran reliever Bill Campbell and minor league catcher Mike “Rambo” Diaz.

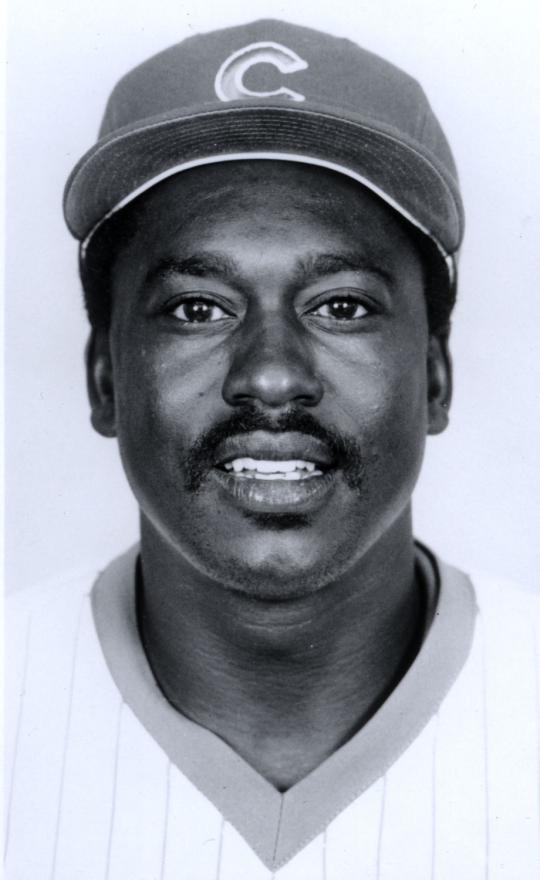

The trade left Matthews stunned. He felt hurt and rejected, but the Cubs made him feel welcome. Team president Dallas Green felt that Matthews represented a perfect fit.

“We needed a screamer, a holler guy, a leader,” Green later told Fred Mitchell of the Chicago Tribune. “When I realized we could get him from the Phillies, I couldn’t say yes fast enough.”

With the Cubs, Matthews enjoyed a career renaissance. Playing in 147 games, Matthews led the National League with 103 walks and a .410 on-base percentage. His OPS of .838 represented his best figure since 1981. Not surprisingly, he became popular with the Wrigley Field faithful, prompting an unusual ritual at the start of each game. As Sarge took his position in left field in the top of the first inning, the Cubs fans in the outfield bleachers stood and saluted the veteran outfielder. As soon as Matthews returned the favor with a salute of his own, the fans took their seats.

As much as any Cub, Matthews’ on-field play and leadership helped drive the team to a surprising National League East title. After the season, the MVP voting from the National League beat writers revealed a fifth-place finish for Matthews, remarkable for a player who had been considered on the downhill side of his career.

In the NLCS, Matthews and the Cubs squared off against another surprise team, the San Diego Padres. Matthews would hit two home runs in the series, but his power output could not prevent the Cubs from losing the final three games of the NLCS and watching their season come to a disappointing end.

In 1985, injuries and age would start to take their toll on the 35-year-old Matthews. Limited to 97 games, he batted only .235 and saw his slugging percentage fall to .406.

Yet, Matthews did not give in. In 1986, he bounced back to play in 123 games and hit 21 home runs, his highest total since the career season of 1979.

Matthews returned to the Cubs in 1987, but was rendered a part-time player and pinch-hitter. With the Cubs committed to Jerry Mumphrey in left field, Matthews became a little-used backup. In mid-July, Chicago dealt him to Seattle for a player to be named later.

The switch to the American League made sense. At 36, Matthews could no longer play the outfield. The Mariners made him their DH, hoping for one last revival with the bat, but he hit only .235 with scant power. With his contract running out at season’s end, Matthews opted for retirement, ending his long and productive 16-year career.

Given his love of the game, Matthews remained in baseball, first as a coach, and later as a broadcaster with Toronto and Philadelphia. He did television work with the Phillies through the 2013 season, when the team decided to make a change in the broadcast booth.

That winter, The Phillies found a new role for Matthews as one of their team ambassadors. He continues to take part in charitable endeavors throughout the community and visits suite holders at Citizens Bank Park during home games. Knowing what we do about Matthews, it’s a safe bet that Sarge takes on the job with the same amount of passion that he did when he slid in between Wayne Garrett and John McNamara.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame