“As far as the toughest receivers, Cannizzaro makes [every stolen base attempt] close even when you get a good jump.”

- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1975 Topps Chris Cannizzaro

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Chris Cannizzaro

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

As we remember Hall of Fame Weekend, my mind invariably turns to the baseball figures we have lost since the last Induction Ceremony. Thoughts of Hall of Famer Jim Bunning and his perfect game on Father’s Day come to mind, as do memories of some of the other players who have died, including Jimmy Piersall, Gene Conley, Anthony Young, and of course, current day players like Jose Fernandez and Yordano Ventura, who passed away long before they should have.

Some of the players we have lost over the last 12 months are less famous on a national scale, but still just as important on a personal level. For me, one of those players was a relatively obscure catcher who spent much of his career as a backup. But his is a name that is known to fans of a certain age, especially those who can remember the dawning days of the New York Mets franchise.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Chris Cannizzaro was a member of the Mets during their inaugural season of 1962. Seven years later, he made his first and only All-Star team. He was never really a star, but was a good catch-and-throw receiver who played for six different National League teams, handled pitchers well and made himself welcome in the many clubhouses that he visited. He was also a player who appeared on one of the stranger cards that the Topps Gum Company ever produced.

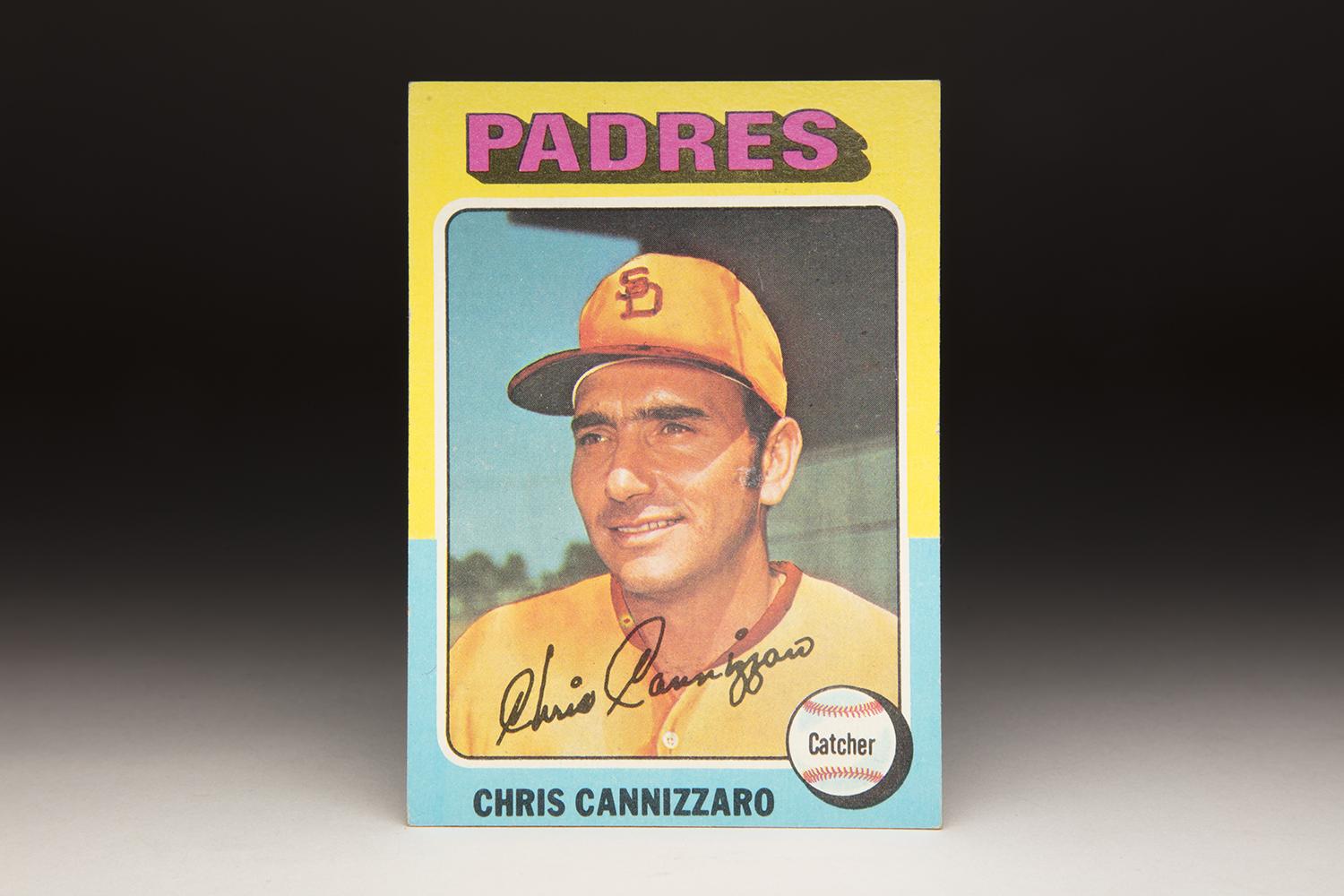

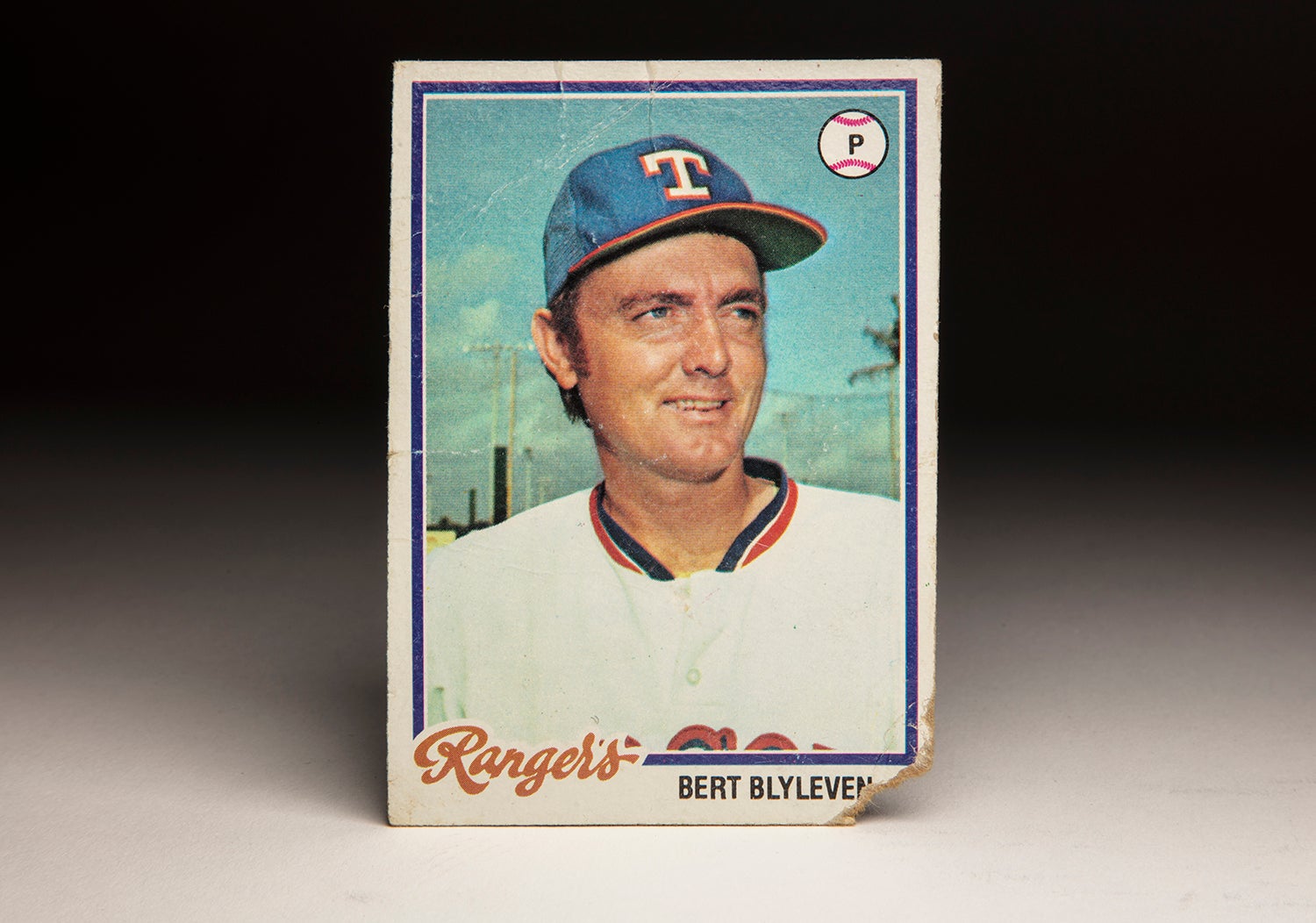

In 1975, Cannizzaro appeared on a Topps card for the final time in his career. The card, which shows him as a member of the San Diego Padres, is just so garish and gaudy, between the bright yellow and powder blue borders and the psychedelic airbrushing of Cannizzaro’s uniform. It looks like the Topps artist mixed some yellow with some brown, splotched the two colors at various points on the photograph, and then added some Crayola to the cap (just for run), while also creating a makeshift “SD.” It’s so revolting, it’s actually good – in a weird 1975 kind of a way.

What’s also interesting about Cannizzaro’ 1975 Topps card is the need to resort to airbrushing in the first place. Cannizzaro played 26 games for the Padres in 1974, and had also played for the team during an earlier stint, so there were opportunities for Topps to acquire photographs of him wearing actual San Diego colors. Somehow an updated photograph of Cannizzaro eluded Topps. And then in 1975, Cannizzaro did not play in the major leagues at all. Opting to go with younger catchers like Fred Kendall and Bob Davis (and veteran ex-Cub Randy Hundley), the Padres assigned Cannizzaro to their Triple-A affiliate, the Hawaii Islanders. For veteran players in the 1970s, there was no better minor league locale than Honolulu. There Cannizzaro served as a player/coach, while also enjoying the beaches and poolside settings of the Hawaiian Islands.

Long before those beaches, Cannizzaro started his minor league career in Decatur, Ill., of the Midwest League. That’s where the St. Louis Cardinals assigned him after first signing him as an amateur ballplayer in 1956. A catcher with a strong throwing arm if spotty receiving skills, Cannizzaro struggled with the bat, hitting only .212 as a Midwest League rookie. But he still managed to make Triple-A by his third season, before being slowed by a stint in the U.S. Army, involving a six-month commitment in 1959.

Cannizzaro made his major league debut for St. Louis at the start of the 1960 season, when manager Solly Hemus included him on the roster as the Cardinals’ fourth-string catcher. (Yes, teams had fourth-string catchers back then, in part because of the rule that allowed teams to start the season with 28 players.) After appearing in a handful of games, Cannizzaro endured a fast demotion to Triple-A Rochester. In 1961, he was supposed to start the season at Triple-A Houston, but did not play a single game there because of what was originally diagnosed as a horrific bout of food poisoning. (It turned out to be appendicitis, requiring surgery.) He missed a month of action, and then received a transfer to Portland, the Cardinals’ new Triple-A affiliate. Remaining there for most of the summer, he finally received a call-up to the Cardinals in August. He played in all of six games, coming to bat only twice. Between the two stints in St. Louis, he played only 13 games, hardly much of a sample size.

The Cardinals liked Cannizzaro, particularly his booming throwing arm, but they had a glut of young catchers who were prospects, including a 19-year-old Tim McCarver. Faced with the impending expansion draft, in which new teams in Houston and New York, would select players from the existing teams, the Cardinals could not protect all of their young catching. They left Cannizzaro available and watched him become property of the Mets.

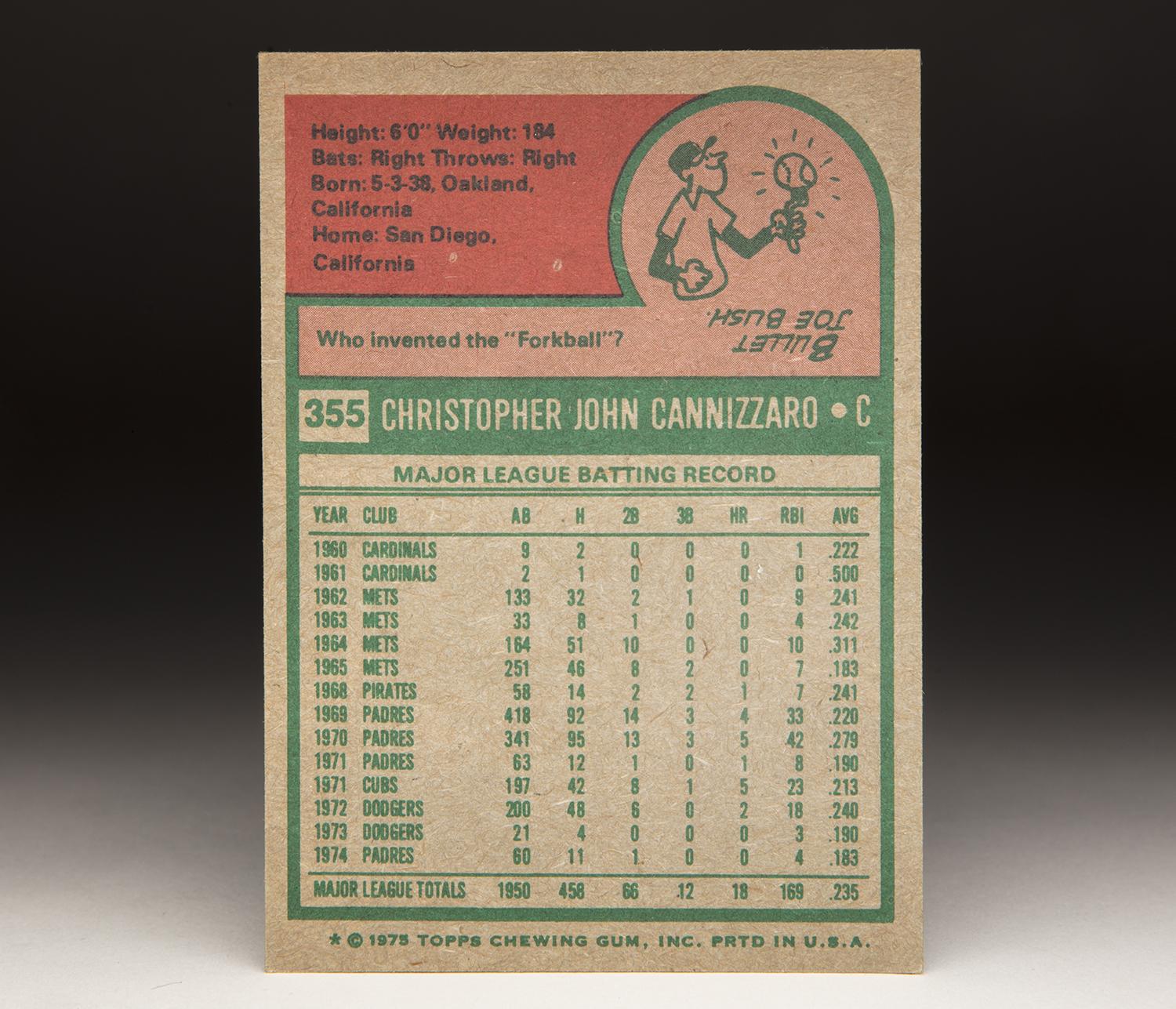

During the expansion draft, the Mets had taken three catchers, including veteran Hobie Landrith. But Landrith couldn’t throw, prompting manager Casey Stengel to turn to Cannizzaro, whose strong arm discouraged opposing teams from running so frequently. Cannizzaro threw well, but he also struggled with passed balls, and didn’t hit at all. The Mets demoted him to Triple-A Jacksonville for a spell, before bringing him back for a second look in late summer. He compiled a .268 batting average in his second stint, raising his season average to a not-so-terrible .241 in 59 games, but without any power.

As a member of the Mets, Cannizzaro also drew some recognition because of the difficulty that Stengel had in pronouncing his name. Struggling with the long Italian name, Stengel called him “Canzoneri,” which was apparently close enough for young Chris to understand. For the rest of his days in New York, he remained Canzoneri – at least to Stengel.

Cannizzaro hoped to become the Mets’ No. 1 catcher during Spring Training in 1963, but a foul tip caught his bare hand in the very first exhibition game and resulted in a broken finger. In a strange way, Cannizzaro believed that the injury actually helped his career. Forced to undergo rehab at minor league Buffalo, the young catcher received regular playing time and through repetition, improved both his hitting and his catching.

In 1964, he returned to New York fulltime to platoon with left-handed hitting catcher Jesse Gonder and delivered a .311 batting average and a .739 OPS, by far the best marks of his career. Responding to Stengel’s claim that he could throw but couldn’t catch, he showed vast improvement in his ability to block pitches and keep balls in front of him, reducing his passed balls totals. At the very least, Cannizzaro seemed like he was capable of being a productive platoon player, based on the strength of his catching and his improved work as a hitter.

By 1965, Cannizzaro was one of only four Mets who remained from the team’s inaugural season of 1962. The Mets decided on a huge role for Cannizzaro, making him the No. 1 catcher. That turned out to be the wrong move. Not ready for the job, Cannizzaro flopped, hitting .183, drawing a mere 28 walks, and hitting no home runs. At 27 years old, he was supposed to be in his prime, but he was instead at the crossroads of his career.

By 1965, Chris Cannizzaro was one of only four New York Mets who remained from the team’s inaugural season of 1962. Pictured above (from left to right): Billy Cowan, Roy McMillan, Johnny Lewis, Ed Kranepool, Joe Christopher, Charley Smith, Bobby Klaus, Chris Cannizzaro and Al Jackson speak with Mets manager Casey Stengel on Opening Day 1965. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

As much as Cannizzaro didn’t hit that season, his catching and throwing continued to receive praise. After all, he led the National League by throwing out 53 per cent of opposing basestealers. During an interview with the Sporting News, Lou Brock was asked about the catchers who made it most difficult for him to steal bases. “As far as the toughest receivers,” Brock said, “Cannizzaro makes [every stolen base attempt] close even when you get a good jump.”

Even with such praise, the Mets moved on from Cannizzaro just before Opening Day in 1966. They traded him to the Atlanta Braves for outfielder Don Dillard. Cannizzaro would never play in a game for the Braves, instead playing the entire season at Triple-A and never receiving the call to Atlanta. That winter, the Braves sent him to the Boston Red Sox as part of a minor deal for pitchers Julio Navarro and Ed Rakow.

Cannizzaro’s time in Boston turned out to be shorter than his expedition to Atlanta. Sometime in February, before the exhibition season even began, the Red Sox traded him to the Detroit Tigers in what is now dubbed an “unknown transaction.” The Tigers hoped that Cannizzaro would become Bill Freehan’s backup that spring, but he did not make the team, instead spending a full summer in Detroit’s system. He then moved on again, this time traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates for outfielder Mike Derrick.

In the span of two seasons, Cannizzaro had spent time in four different organizations, but without appearing in a single major league game for anyone. His career spinning out of control, Cannizzaro desperately needed some stability. He would find some in Pittsburgh – eventually.

At first, the Pirates sent him to their affiliate at Triple-A Columbus, where he spent the first half of the summer. In August, the Pirates brought him up and made him their backup catcher, supporting another strong defender in Jerry May. Cannizzaro played respectably, hitting .241 and compiling an OPS of .740, the latter a respectable figure for a backup catcher. The season was also notable for his milestone first home run, coming in his fifth full season in the major leagues.

For the second time in his career, Cannizzaro faced the possibility of being taken in the expansion draft. The Pirates liked the job that Cannizzaro did for them, but as a backup catcher, it would have been difficult to justify protecting him. So the Pirates did not, but the two expansion teams in Montreal and San Diego still bypassed him.

Cannizzaro reported to his second spring training with the Pirates, expecting once again to serve as the Bucs’ backup catcher. Then came the surprise. In late March, the Pirates made a trade, sending Cannizzaro to one of the expansion teams, the Padres, who had decided not to select him in the wintertime draft. Cannizzaro and pitcher Tommy Sisk headed to San Diego for a package of outfielder Ron Davis and infielder Bobby Klaus.

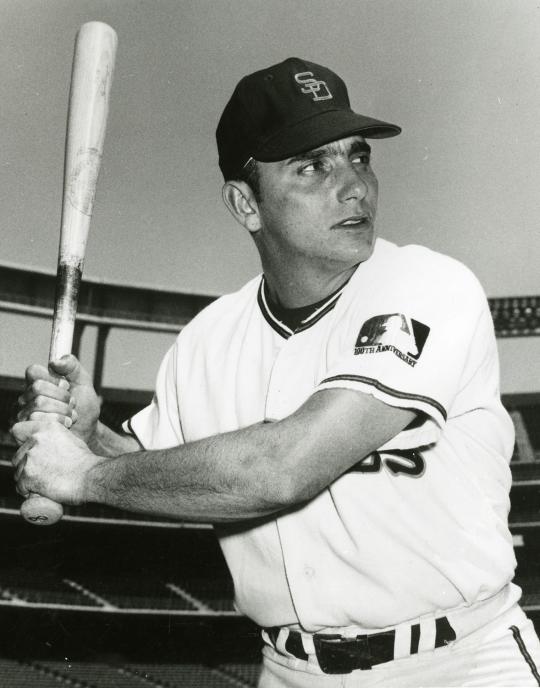

Cannizzaro welcomed the trade with open arms, in part because it placed home closer to his family on the West Coast, but also because he knew that the Padres desperately needed catching. Winning the Padres’ No. 1 catching job that spring, Cannizzaro didn’t hit much in 1969, but he played his usual high-caliber defense behind the plate and kept the opposition running game in check. Given the rule that each major league team needed to be represented in the All-Star Game, Cannizzaro seemed like as good a choice as any. The National League selected him as one of two backups behind perennial starter Johnny Bench. Cannizzaro did not play in the game, but still received some All-Star glory for the first time in his career. The trip to the game, which was held in Washington, also included a visit to the White House.

For the season, Cannizzaro batted .220 with an OPS of .587, but was so adept at handling a young pitching staff that the Padres once again made him their starter in 1970. He didn’t play as much – his workload reduced from 134 to 111 games, but he hit much better, raising his batting average to .279 and his on-base percentage to .366. He played better than he did in 1969, owning a .319 batting average at the All-Star break.

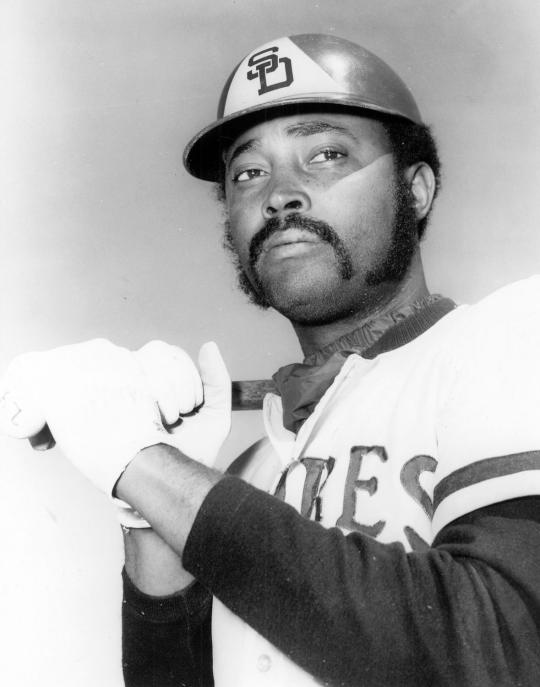

Somehow, he didn’t make the All-Star team this time, even though he deserved it more. “I don’t believe baseball people realized what I was doing,” Cannizzaro said a year later. “I mean, the last place people would look to find what Cannizzaro was batting would be in the top 10 hitters [category].” Instead National League manager Gil Hodges selected teammate Clarence “Cito” Gaston as the Padres’ All-Star representative.

In 1971, Cannizzaro started his third campaign in San Diego, but didn’t last the summer with the Padres. After a slow start at the plate, the Padres dealt him in May, sending him to the Chicago Cubs for utility infielder Garry Jestadt. With a season-ending injury suffered by Randy Hundley, the Cubs badly needed a catcher. Cannizzaro did the bulk of the receiving for Chicago, while occasionally giving way to the lefty-swinging J.C. Martin.

After doing his usual job of good fielding and light hitting, the Cubs sold Cannizzaro on waivers that winter. The Los Angeles Dodgers, who were unhappy with the defensive quality of their catchers, put in the $20,000 claim and made Cannizzaro part of a rotation that included veteran Duke Sims and a young Steve Yeager.

The following season, injuries limited Cannizzaro to 17 games, but he took on a far more vital role as an unofficial coach. Upon instructions from manager Walter Alston, Cannizzaro spent much of his time advising and tutoring two of his young teammates, roommate Bill Russell and fellow catcher Joe Ferguson. Using his old school approach, but with a soft touch, he found a way to get through to the two youngsters.

“He’s as smart a baseball man as we have and I told him in spring that I wanted him to take charge of those two,” Alston told Ross Newhan of the Los Angeles Times. “I told him he had the authority of a coach… He has done one hell of a big job with Russell and Ferguson.”

Unfortunately, Cannizzaro’s good work did not translate into job security. He was now 34 years old, with his playing skills having declined, and received his unconditional release in October. Given his popularity in the clubhouse, many of the Dodgers were upset when they heard the news that he had been cut loose.

In January of 1974, the Houston Astros signed Cannizzaro and invited him to Spring Training, but he did not make the Opening Day roster. Instead, he settled for an assignment to the Triple-A Denver Bears, where he served as a player/coach for the first half of the season. He even managed the Bears for one game when Frank Verdi was called away from the team for personal reasons. On Aug. 1, Cannizzaro returned to the major leagues, but this time with the Padres, who reacquired him in a straight cash purchase. He played in 26 games in his return to San Diego, but an OPS of .458 dictated a return to the minor leagues in 1975 and a final season as a player/coach.

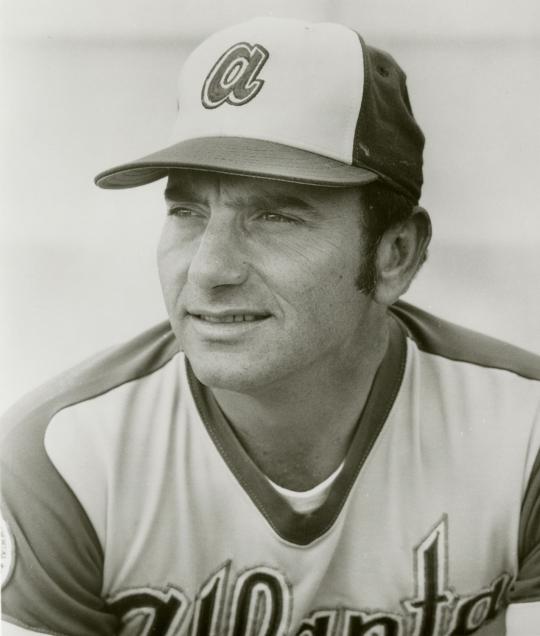

As a member of the New York Mets, Chris Cannizzaro drew some recognition when Casey Stengel continually mispronounced the catcher's last name, referring to him as “Canzoneri.” (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

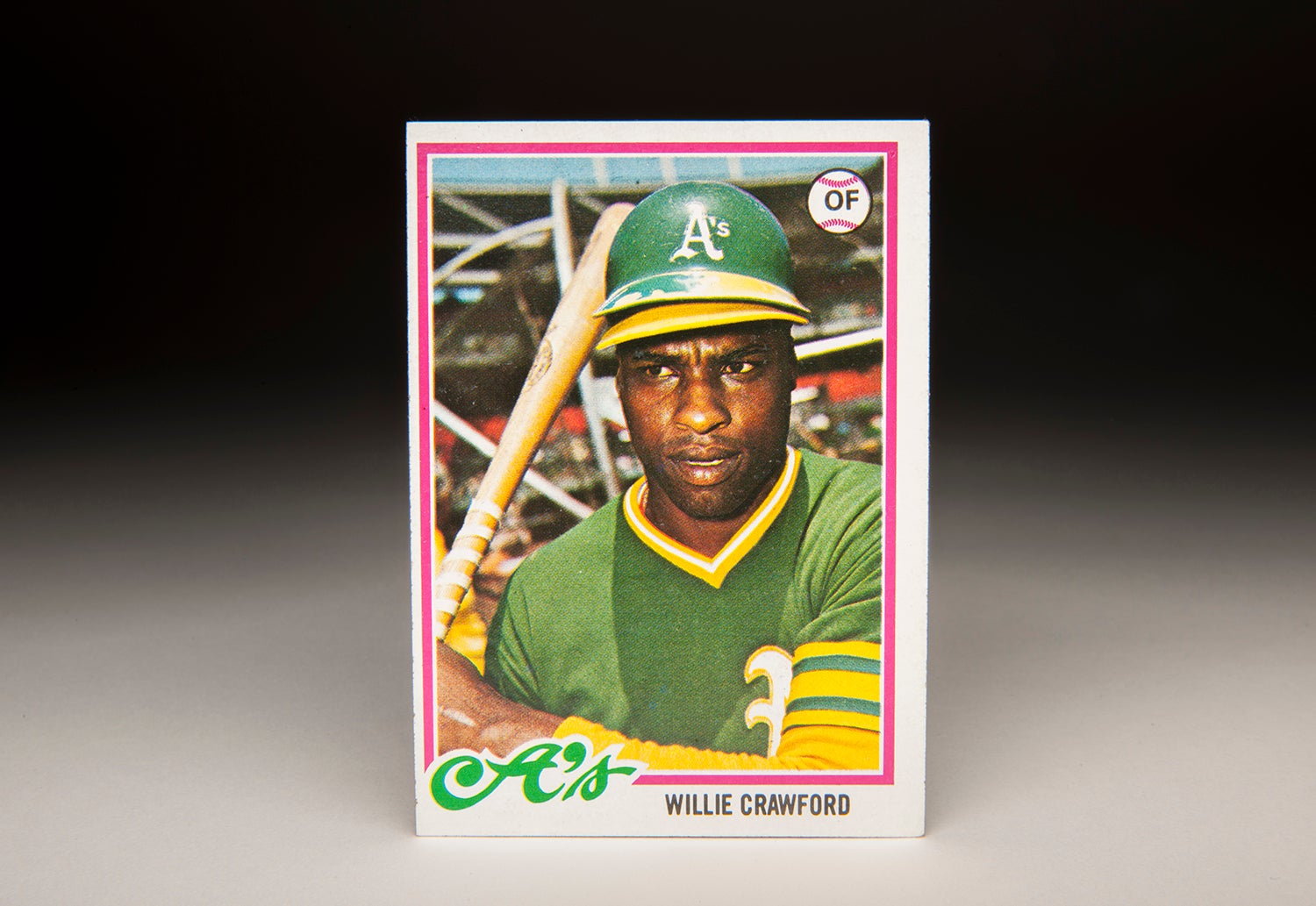

The St. Louis Cardinals liked catcher Chris Cannizzaro, but they had a variety of young catchers who were prospects, including a 19-year-old Tim McCarver (pictured above). (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

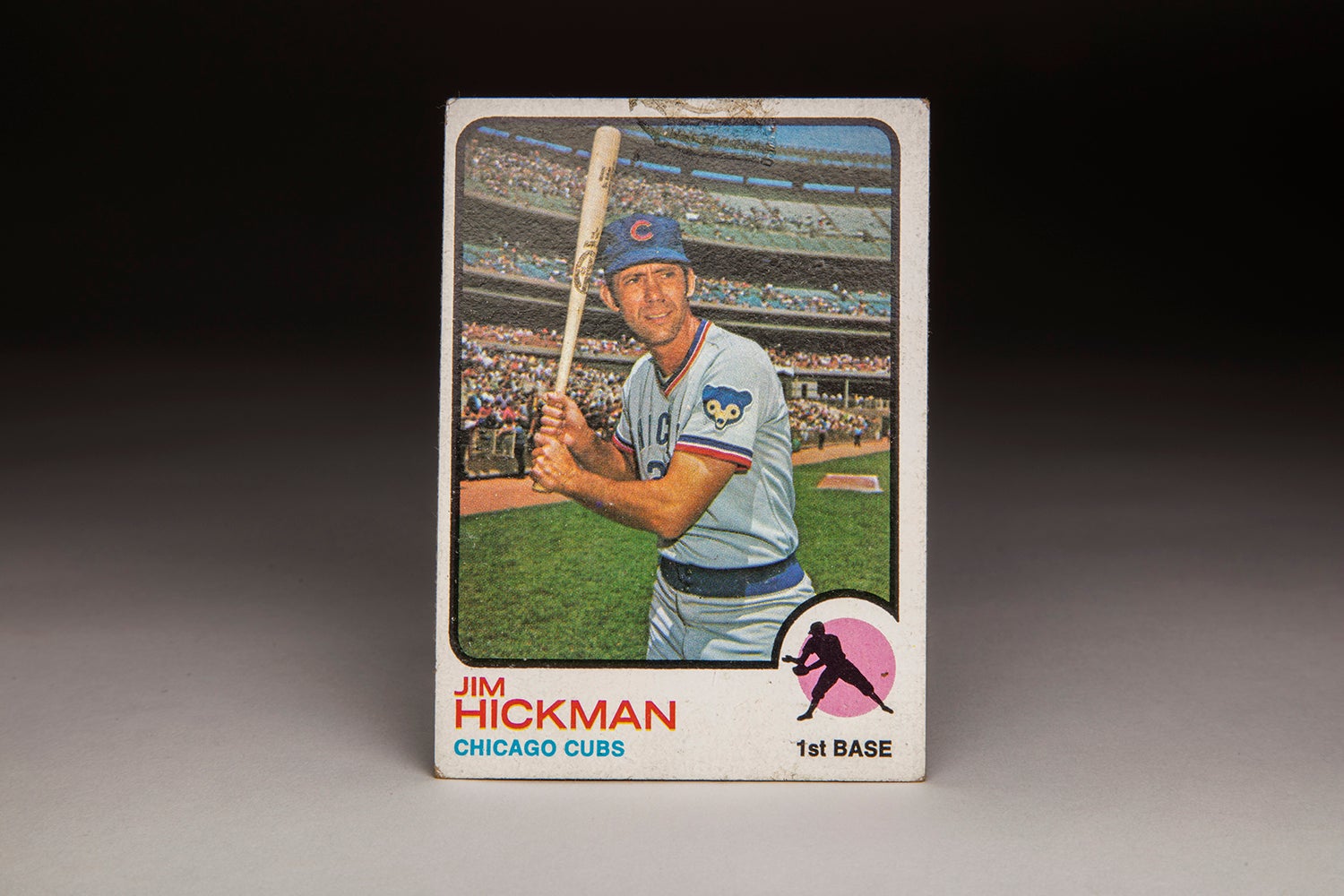

Chris Cannizzaro's first stint with the San Diego Padres came from 1969-1971. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

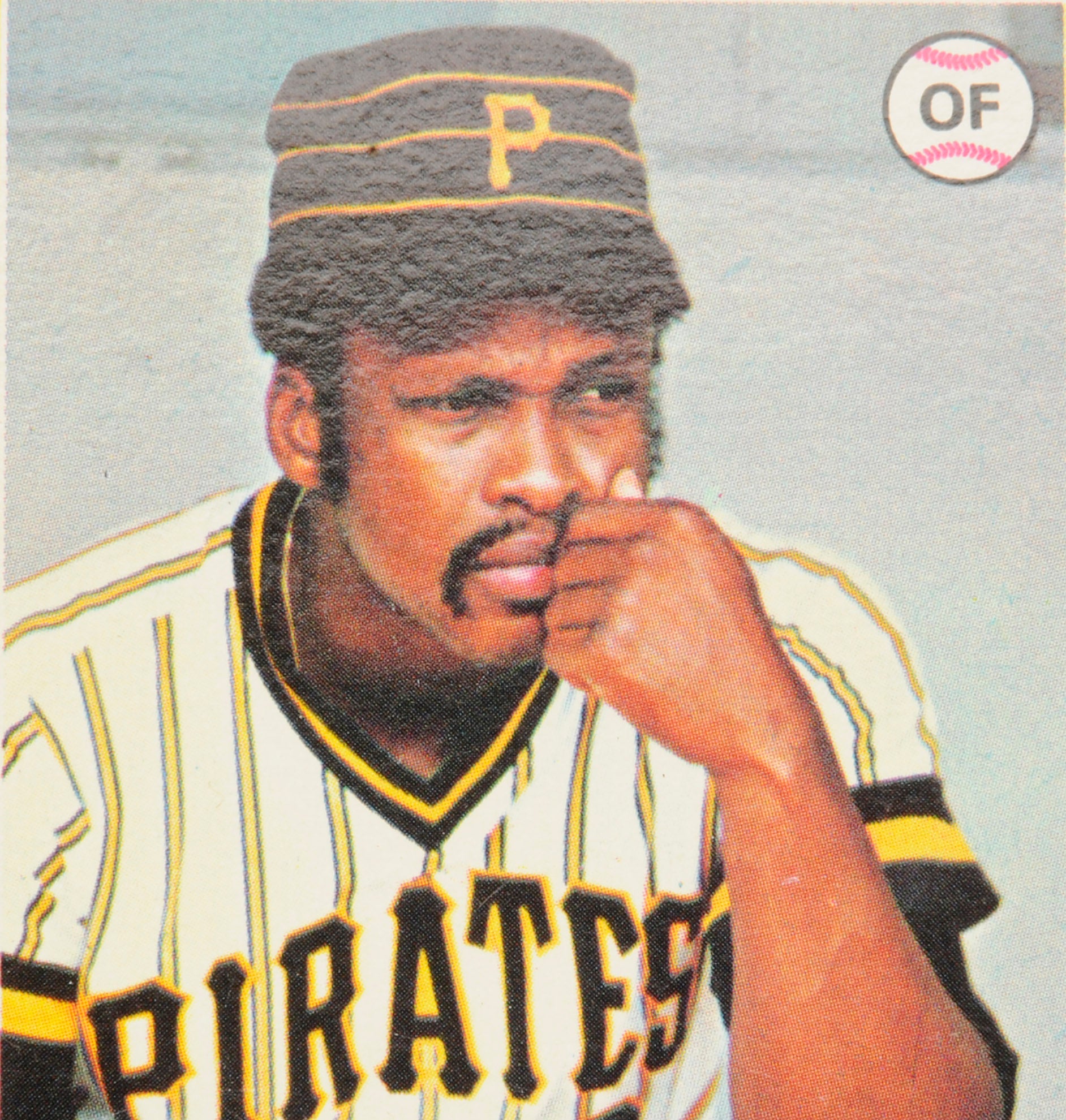

Although Chris Cannizzaro owned a .319 batting average at the All-Star break in 1970, National League manager Gil Hodges chose Clarence “Cito” Gaston (pictured above) as the team's All-Star representative. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

In light of his acumen as a quality catcher and intelligent player, it made perfect sense for Cannizzaro to remain in the game. The Braves hired him as bullpen coach, while also giving him a chance to work with their young catchers. After the 1978 season, he moved on to the California Angels, first as a coach and then as a minor league manager. He hoped to eventually earn a major league managing job, but the opportunity never came. Instead, he did good work developing prospects in the Angels’ system, including future standouts like Tom Brunansky and Mike Witt. He also helped out his former teammate in San Diego, Randy Jones, by becoming a longtime coach at the former pitcher’s instructional camp.

In his later years, Cannizzaro was diagnosed with lung cancer. After a lengthy battle, he succumbed to the disease in December of 2016, but not before the Padres honored him for their service to the team. As part of the All-Star Game festivities in San Diego, the Padres formally recognized Cannizzaro as the first All-Star representative in the franchise’s history.

It was a nice gesture on the Padres, who likely knew that Cannizzaro did not have long to live. When he took the field at Petco Park, he was frail and thin, his body clearly showing the effects of emphysema.

Like a lot of fans, I’ll prefer to remember Cannizzaro the way he was on his 1975 Topps card: Smiling and vital and still in the prime of his life. And let’s not forget those gaudy, surreal colors that Topps draped him in, making the card such a memorable one. It’s a card that makes you want to stare at it a little longer, while remembering a smart, tough player who left us not too long ago.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame