- Home

- Our Stories

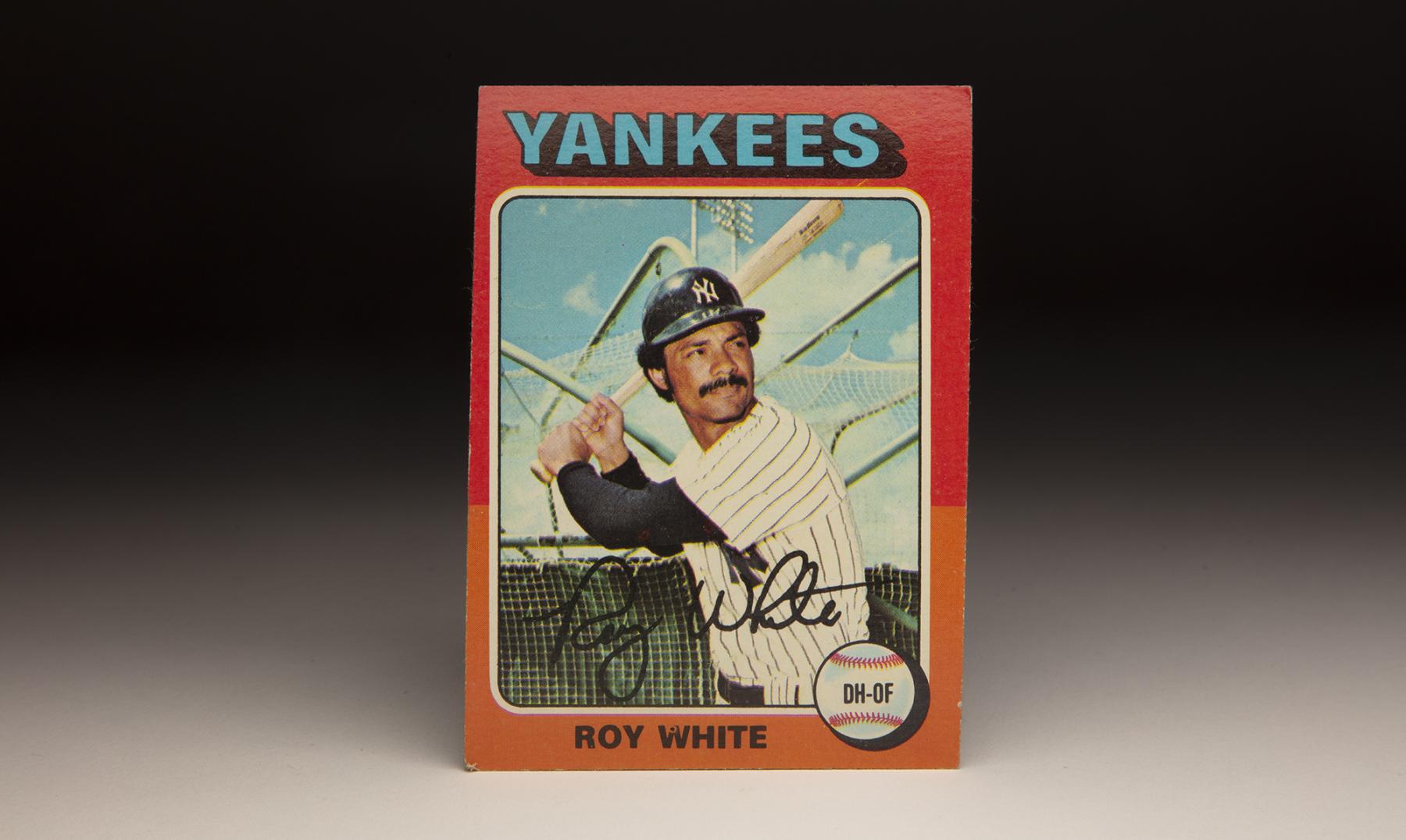

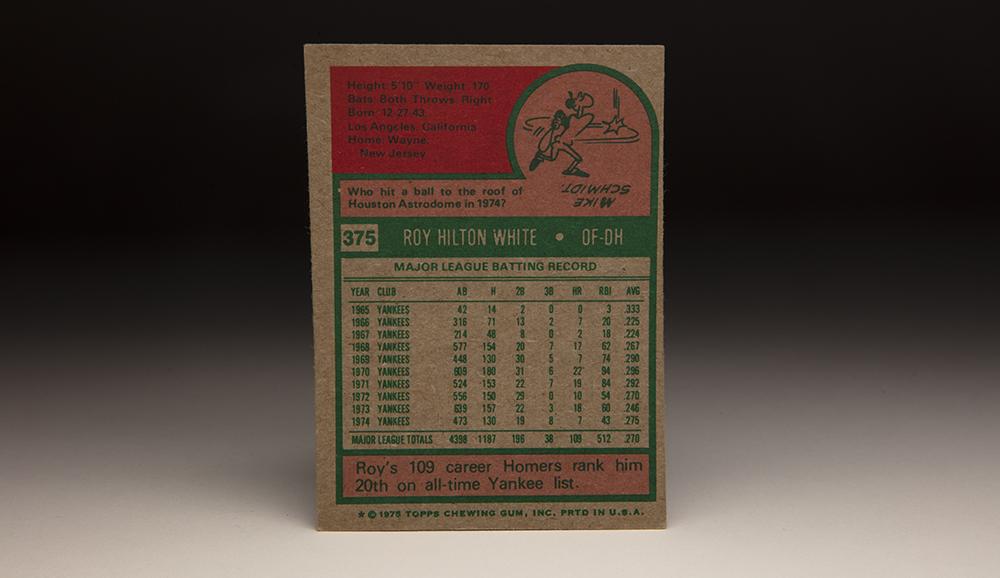

- #CardCorner: 1975 Topps Roy White

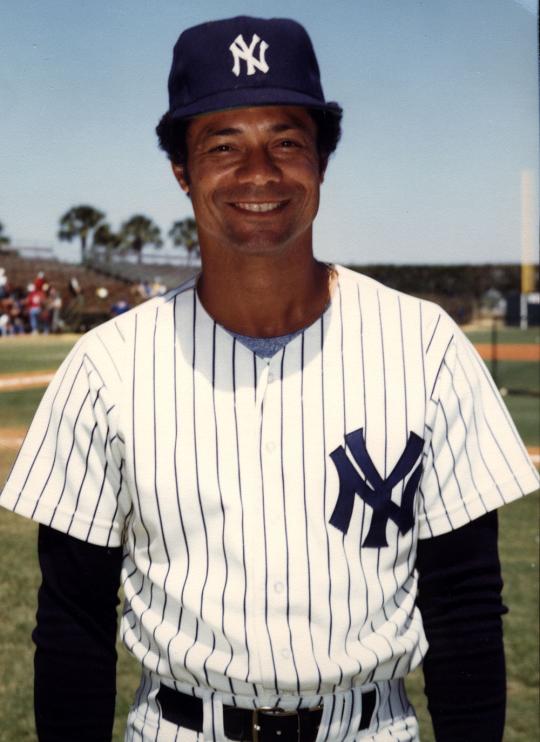

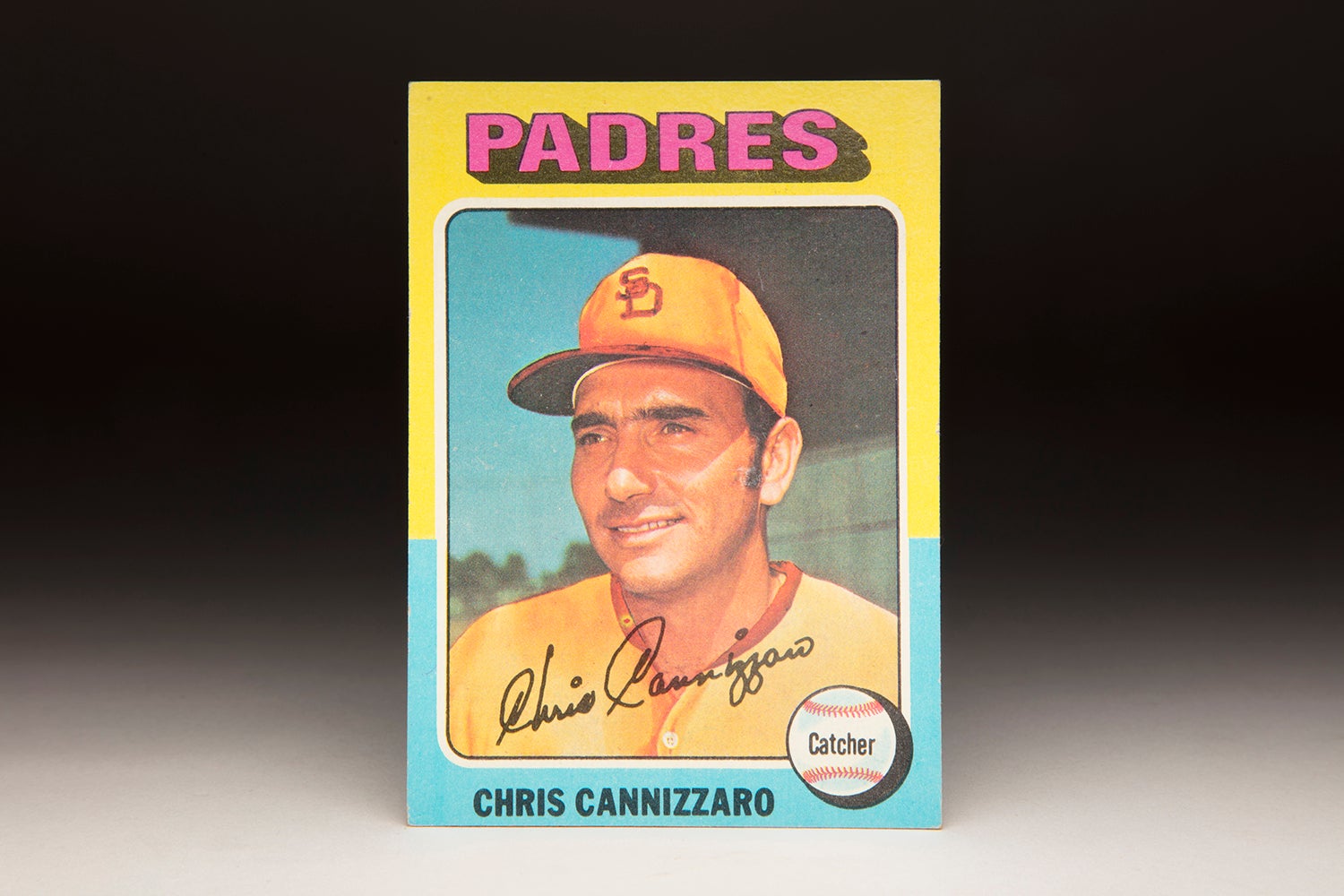

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Roy White

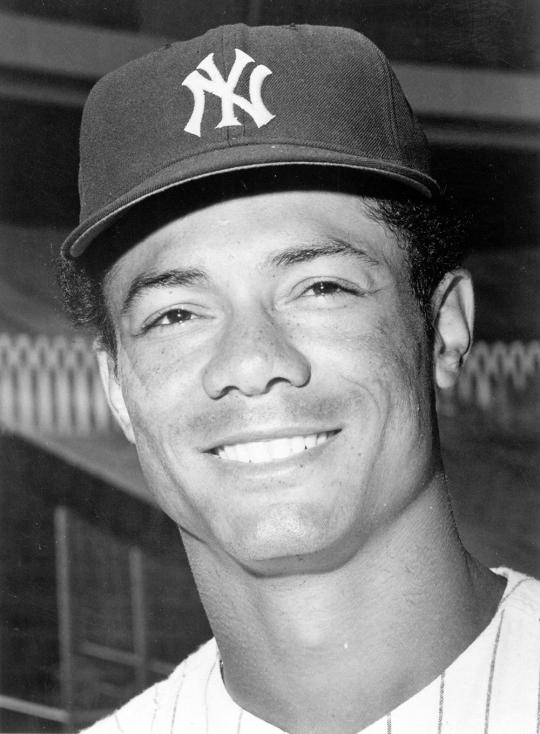

He connected two championship eras of the New York Yankees, debuting the season their great 1950s and 60s dynasty ended and leaving the team following their rebirth in the late 1970s.

In between, Roy White established himself as one of the best multitalented players in the game – and one of its most underappreciated stars.

Born Dec. 27, 1943, in Compton, Calif., Roy Hilton White starred on the diamond and the gridiron for Centennial High School. As a switch-hitting second baseman, White attracted scouts and graduated in 1961 – with several colleges recruiting him as a football player.

Yankees Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

But White was focused on baseball and drew interest from the Angels and Dodgers. The Yankees, however, won him over with a reported $6,000 signing bonus. As a switch-hitter with some pop and speed, White was fast-tracked through the Yankees system.

“Every kid in our neighborhood was a switch-hitter,” White told the Miami News of his journey to becoming a switch-hitter. “We all tried to imitate the big league players. Hitting a can down the street with a stick, I’d swing left-handed if I imagined myself a (Stan) Musial or some other left-handed hitting hero. And right-handed I was (Willie) Mays or some other right-handed star.”

White played Class D and Class B ball in 1962, then jumped onto prospect lists in 1963 when he hit .309 with 117 runs scored and 100 walks as a second baseman for Class A Greensboro of the Carolina League.

He took a step backward in 1964 at Double-A Columbus of the Southern League in 1964 when he hit .253, but returned to Columbus in 1965 and hit .300 with 19 homers, 22 stolen bases, 85 walks and 103 runs scored while leading the team to the Southern League title.

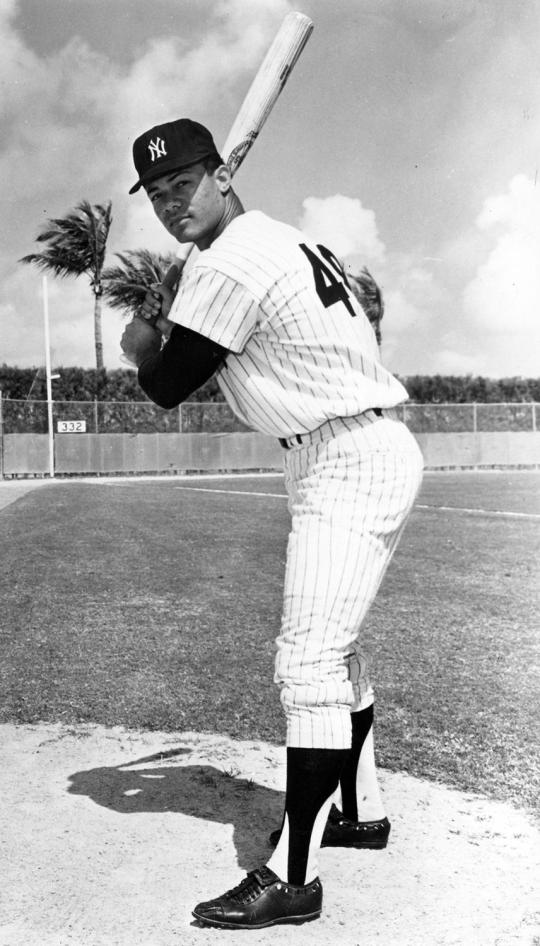

White earned a September call-up to the Yankees, hitting .333 over 14 games – mostly in right field. After a trip to the highly competitive Florida Winter Instructional League following the season and a productive spring with the Yankees in 1966, White earned a spot on the big league roster. He was named the winner of the James P. Dawson Award by the team’s beat writers as the top rookie in Yankees camp – an award that had previously been won by players like Tony Kubek, Johnny Blanchard and Tom Tresh.

“I’m looking forward to it with no apprehension,” White told the Miami News of his new role, which included starting in center field in the Yankees second game of the 1966 season.

White drew immediate notice for wearing glasses during games – an uncommon sight at the time. He would wear eyeglasses or corrective lenses throughout his career.

“At Greensboro in ’63, I began getting spots before my eyes and got scared,” White said. “I thought I might be getting glaucoma or something. I went to an eye doctor and he said it was just nearsightedness and prescribed glasses.”

White finished his rookie season with a .225 batting average and 14 stolen bases in 115 games, getting regular work in left field throughout May and June. But the Yankees finished in last place that season, a shocking development for a team that had won the American League pennant just two years earlier and hadn’t completed a season in the AL cellar since 1912.

White seemed to be a part of the rebuilding plan for New York, but a week before the 1967 season began, White found himself back in the minors.

On April 3, 1967, the Yankees acquired infielder John Kennedy from the Dodgers in exchange for Jack Cullen, John Miller and cash. As part of the deal, the Yankees agreed to send White to the Dodgers’ Triple-A team in Spokane, where he was moved to third base.

“Yes, I was shocked,” White told the Spokane Chronicle, “because I thought I would be with the (Yankees) this season.”

The Yankees pledged to keep White at Spokane for the entire year. But once White proved all he could at Triple-A, a deal was worked out to let him return to New York. When White rejoined the Yankees on July 19, he was leading the Pacific Coast League with a .343 batting average.

“It’s a crime to keep (White) in the minors the way he’s playing,” Dodgers general manager Buzzie Bavasi told the New York Daily News.

White moved into the Yankees starting lineup as a third baseman, but was soon switched back to the outfield. He finished the season with a .224 batting average in 70 games.

White made the Yankees’ Opening Day roster as a bench player in 1968, then began getting regular playing time in center field in May when Bill Robinson and Steve Whitaker were mired in slumps. By late May, White was the Yankees’ starting left fielder.

“The way White came out of nowhere and became the regular left fielder may be an omen for me,” Robinson told The Record in Hackensack, N.J., as he waited for an opportunity to play regularly.

White, however, never relinquished his hold on the job. By the end of the 1968 season, White had totaled 17 homers, 89 runs scored, 62 RBI, 20 steals and 73 walks to go with a .267 batting average.

He hit out of the cleanup spot in 47 of his 159 games that year, and was honored as the American Amateur Baseball Congress Graduate of the Year for 1968.

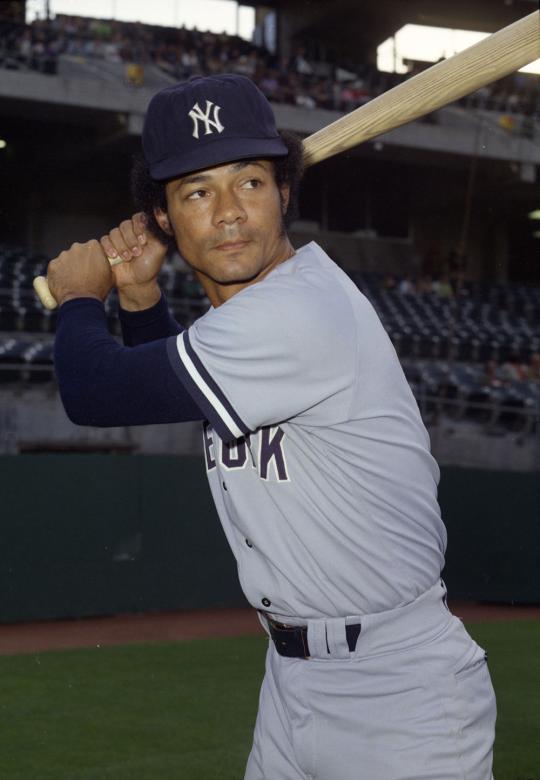

Now entrenched as the Yankees everyday left fielder, White hit .290 with seven homers, 74 RBI and 18 stolen bases in 1969 despite missing two weeks while serving in the Army Reserve. He was named to his first All-Star Game that summer and received the same honor in 1970 – the only Yankees position player selected to either team.

In 1970, White gained notice as one of the game’s best young hitters when he played in 162 games and hit .296 with 22 homers, 109 runs scored, 94 RBI, 24 steals and 95 walks. The Yankees finished with 93 wins and in second place in the American League East but had gone six straight years without making the postseason.

White, meanwhile, was criticized in some circles for not embracing a more colorful style.

“Roy White does his job as best he can,” White told the Newspaper Enterprise Association. “If people want to make a big deal out of it, fine. If not, fine, too.

“People talk about having color – what do they call it, charisma? All this charisma stuff is fine, but you still have to produce.”

White continued to produce for the Yankees – even as an unconventional cleanup hitter who choked up on the bat. He hit out of the No. 4 hole in the Yankees lineup 63 times in 1970 and 100 times in 1971 when he batted .292 with 19 homers, 84 RBI, 14 steals and 86 walks.

“Roy could be one of the finest leadoff men in the game,” Yankees manager Ralph Houk said. “But I just can’t afford to use him up there. The day I can bat Roy first, you’ll know we’ve improved.”

White led the AL in walks with 99 in 1972 while serving once again as the Yankees primary cleanup hitter. But after hitting just 10 home runs that season, White was moved to the No. 2 hole in 1973. White led the AL with 723 plate appearances that year while hitting .246, scoring 88 runs to go with 18 homers and 60 RBI.

Defensively, White’s subpar arm was the target of criticism in the press, but he played every one of his 162 games in left field that year. The Yankees, however, finished a disappointing 80-82, and Houk was replaced by Bill Virdon for the 1974 season. Virdon started White in left field on Opening Day, but soon moved White into a DH/bench role that did not please the 30-year-old White.

“I’ve been overlooked this year and I want to be traded,” White told United Press International late in the season when the Yankees were pushing for the AL East title – only to fall two games short of the Orioles. “Nothing can change my mind – not even a World Series appearance. My ego’s been severely bruised.”

White finished the season with a .275 batting average, seven homers and 43 RBI in 136 games. But in 1975, Virdon was dismissed 104 games into the season – and White embraced the new regime of Billy Martin, hitting .282 with 20 RBI and 22 runs scored over the team’s final 56 games.

Then in 1976, Martin put White in left field and the No. 2 spot in the batting order and kept him there. White responded by hitting .286 with 14 homers, 65 RBI, an AL-best 104 runs scored, a career-high 31 steals and 83 walks. The Yankees, re-energized by Martin and owner George Steinbrenner, won their first AL pennant in 12 years.

White hit .294 in the ALCS against the Royals in his first postseason action, going 1-for-2 with two walks, two runs scored and an RBI in the decisive Game 5 victory. He hit just .133 in the four-game sweep against the Reds in the World Series, but the Yankees had clearly returned to being one of baseball’s top teams.

In the tumultuous 1977 season, White served as a steadying force as the Yankees again won the AL East and defeated the Royals in the ALCS. White hit .268 with 14 homers and 72 runs scored in what would be his last season as the Yankees regular left fielder, but came to the plate only eight times in the postseason as Martin used Reggie Jackson, Mickey Rivers, Lou Piniella and Paul Blair in the outfield on a regular basis.

But after 13 seasons in the big leagues, White finally had his World Series ring when the Yankees defeated the Dodgers in six games.

White began the 1978 season platooning with Piniella in left field as rumors swirled that the team would try to acquire a replacement.

“There’s really no reason to look for another left fielder,” teammate Willie Randolph – who had been mentored by White – said. “But if (George Steinbrenner) wants to look, he can look.”

Relegated to a part-time role, White hit .269 in 103 games – including a .337 average over the final 26 games of the season as the Yankees rallied to catch the Red Sox in the AL East. With Bob Lemon having replaced Martin during the summer, White saw action in every postseason game in 1978 – hitting a combined .325 in 10 games in the ALCS and World Series with two homers, five RBI and 14 runs scored as the Yankees repeated as champions.

With the Yankees trailing 2-games-to-0, White’s first inning home run in Game 3 set the tone for New York’s comeback as the Yankees won four straight.

In 1979, the 35-year-old White appeared in just 81 games and hit only .215. The Yankees allowed him to become a free agent following the season – and White shocked the baseball world by signing with the Yomiuri Giants of the Japanese Central League on Feb. 17, 1980, despite receiving several offers from big league clubs. His deal was for a reported $500,000.

In 1980, White hit 29 home runs and drove in 75 runs for the Giants, then hit .273 with 13 homers and 55 RBI in 1981 to help Yomiuri win the Central League title and the Japan Series. After hitting .296 in 1982, White retired as an active player.

“I didn’t go in there trying to tell them how we did it with the Yankees,” White told Knight Ridder Newspapers. “And after I hit three home runs in one game, I was pretty well accepted.”

White returned to the Yankees as a coach in 1983 and also served on the staff during the 2000s.

When White left the Yankees as a player following the 1979 season, he was fifth all-time in franchise history in games played (1,881), eighth in hits (1,803), fourth in walks (934) and second in stolen bases (233).

A bridge between the teams of Mantle and Jackson, Roy White carved out his own legacy in Yankees lore.

“I was oblivious to the turmoil of the 1970s teams,” White told the New York Daily News. “I had to work hard to be a major league player, to make myself valuable to the club. I was just trying to keep my job.

“George (Steinbrenner) wanted an all-star at every position. He didn’t know that that doesn’t work. I later heard (Yankees general manager) Gabe Paul always convinced George to keep me. He’d say: ‘We need Roy, he fits well with this ball club.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum