- Home

- Our Stories

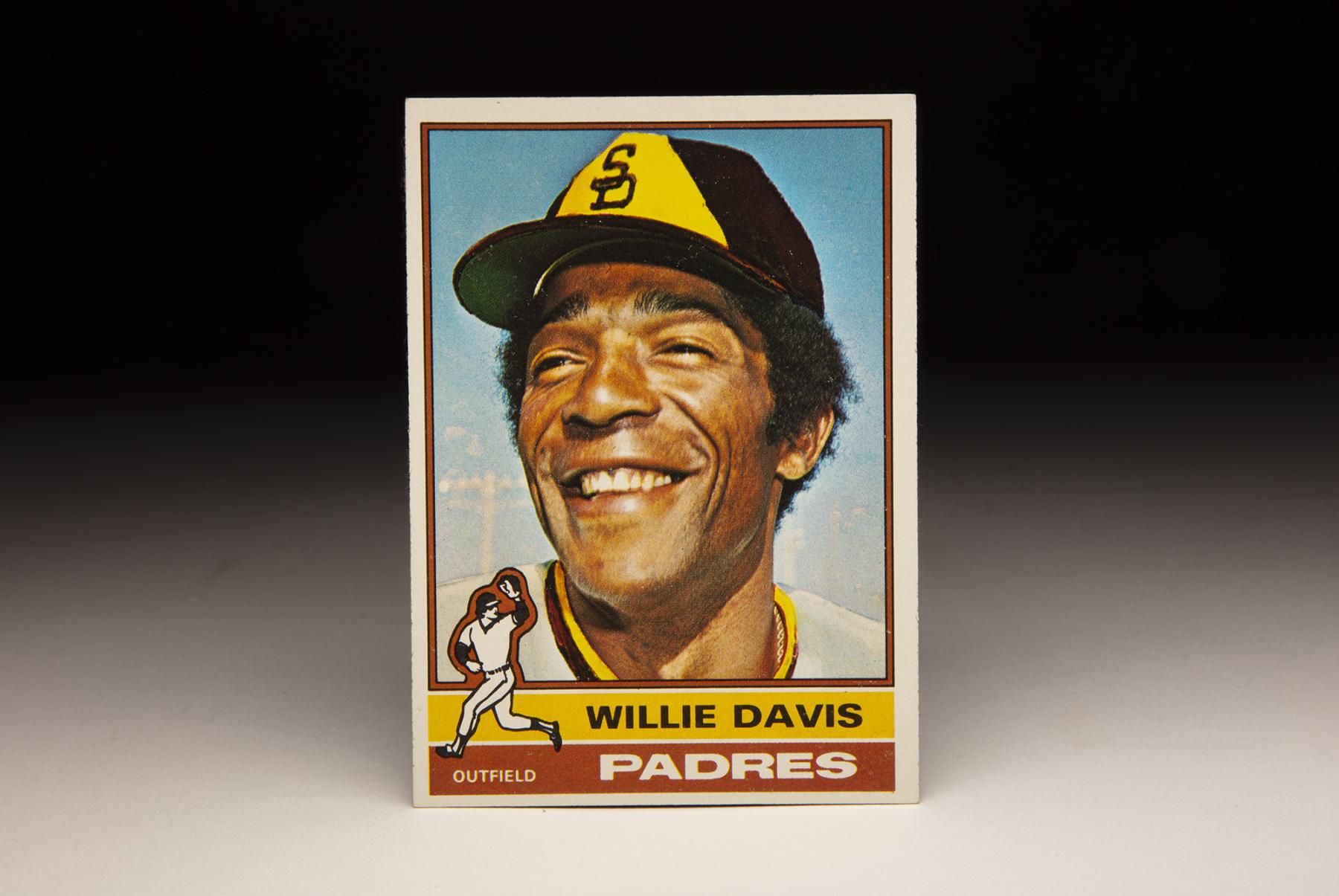

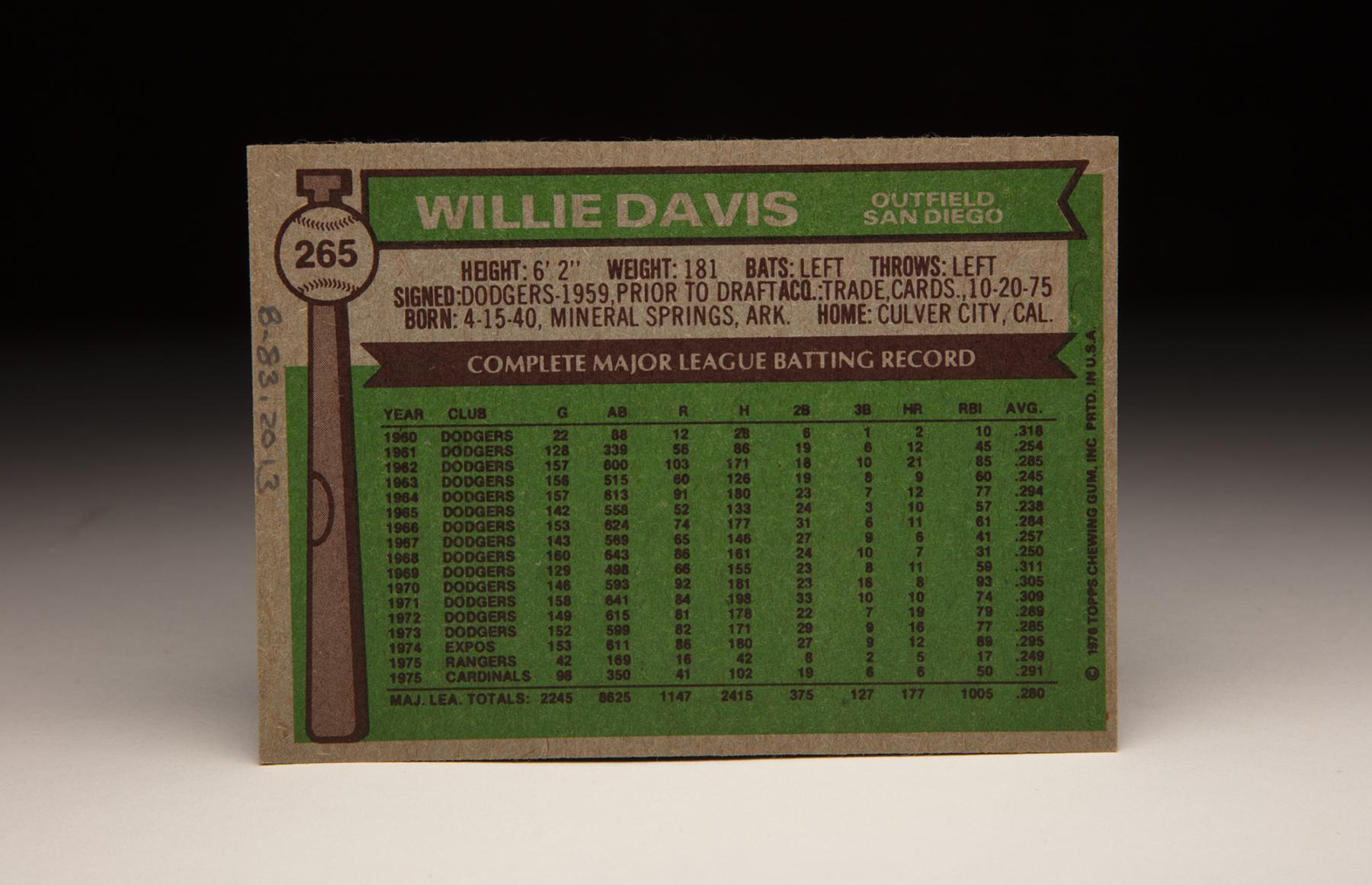

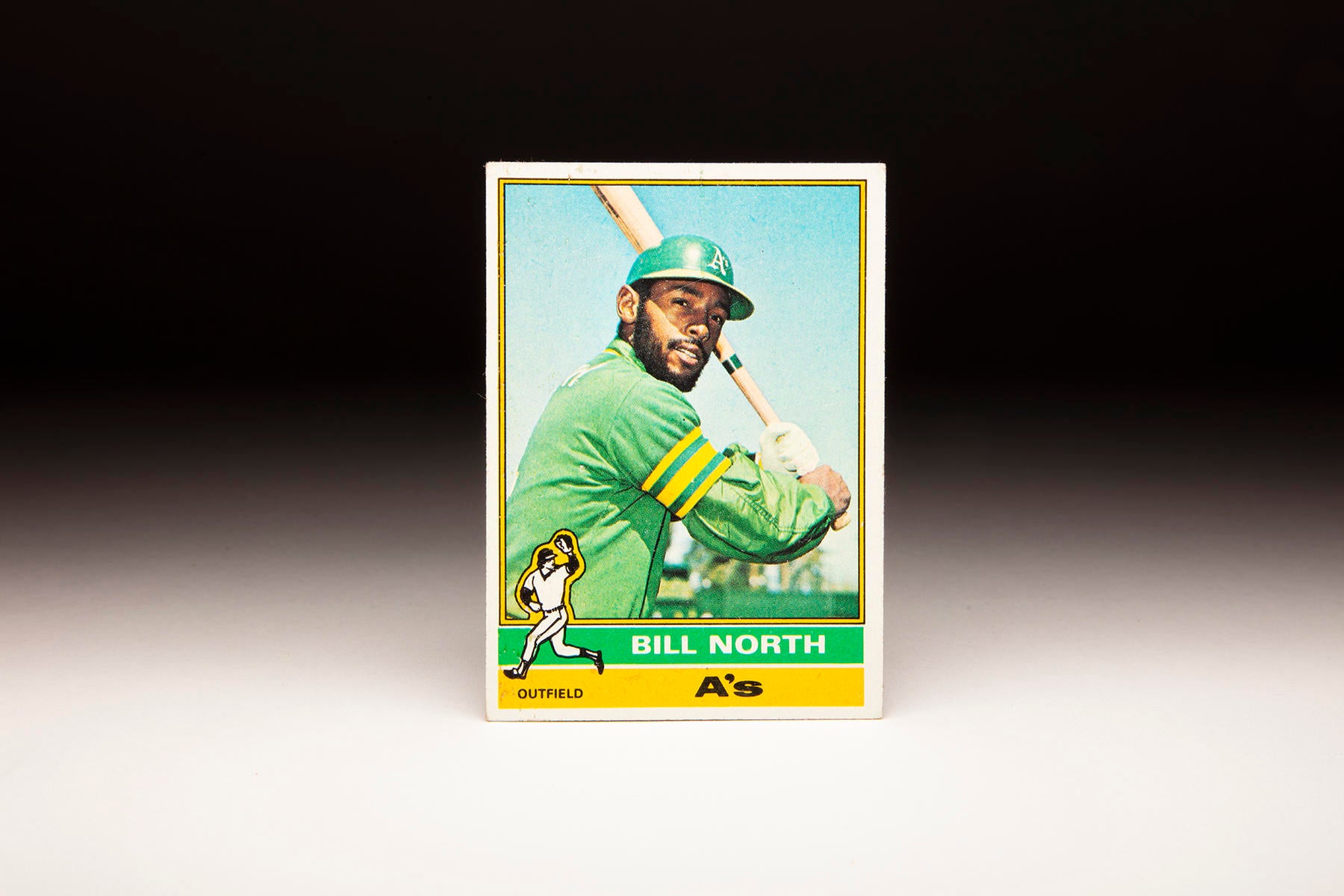

- #CardCorner: 1976 Topps Willie Davis

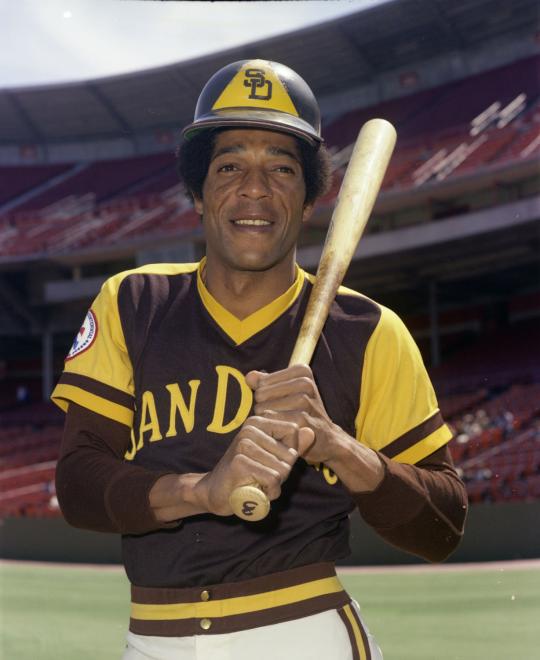

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Willie Davis

The two decades of play from 1960-79 featured some of the most suppressed offensive totals in the game’s history.

In that pitcher-dominated era, Pete Rose had the most hits with 3,372. The next five names on that list – Lou Brock, Carl Yastrzemski, Billy Williams, Hank Aaron and Brooks Robinson – all have been enshrined in Cooperstown.

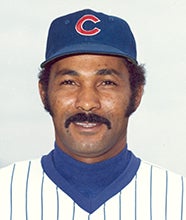

Then comes Willie Davis and his 2,561 hits, 398 stolen bases and 60.7 career Wins Above Replacement.

There may not have been a more underappreciated player in that time.

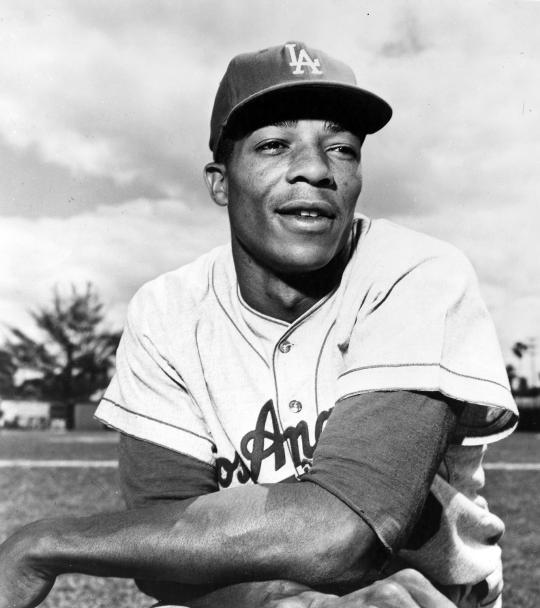

Born April 15, 1940, in Mineral Springs, Ark., Davis moved with his family to Los Angeles, where he became a schoolboy track and field sensation at Roosevelt High School. He set a new long jump record of 25 feet, 5 inches, breaking the high school mark held by Jesse Owens for almost 30 years while registering a blistering 9.5 seconds in the 100-yard dash.

Dodgers Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“I played no baseball until I went to high school,” Davis told the New York Daily News. “I actually knew very little about the game.”

But when the Dodgers offered him a $5,000 bonus – with a chance to make another $6,000 if he made the big league club – Davis turned to baseball. And with the help of a Dodgers scout named Kenny Myers, Davis learned the fundamentals.

“Kenny taught me all I know,” Davis said. “Everything. And that means from how to hold the bat to how to throw a baseball.”

Davis debuted with the Class B Green Bay Blue Jays in 1959 but struggled, prompting the Dodgers to send him to Class C Reno of the California League. There, Davis hit .365 with 71 extra base hits and 33 steals in 117 games.

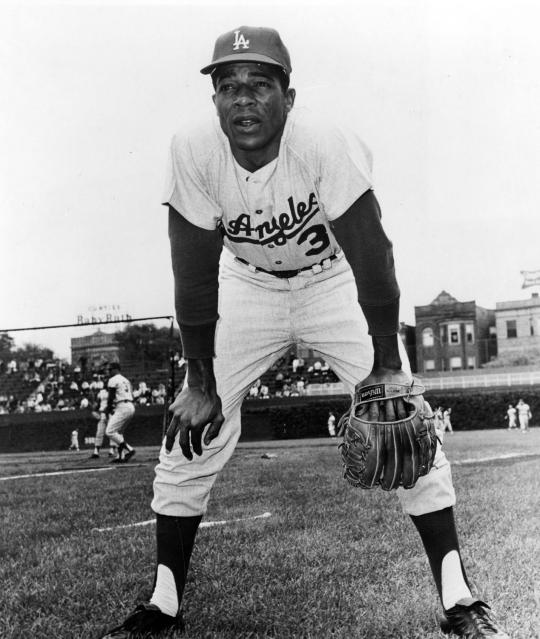

Promoted to Triple-A Spokane in 1960, Davis hit .346 with an incredible 26 triples, scoring 126 runs in 147 games. The Dodgers called him up to the big leagues in September, where he hit .318 in 22 games and stamped himself as one of the game’s top prospects. ABC TV produced a documentary on his life during his rookie season – a testament to a player many thought was the next Willie Mays.

“The first time he hit the ball for us,” Dodgers manager Walter Alston told the Associated Press in the spring of 1961, “Gus Bell of Cincinnati dropped his one-hop liner. When he looked up, (Davis) was sliding into second base.”

Davis hit .254 with 12 homers, 45 RBI and 12 steals in 128 games in 1961, then took hold of the Dodgers’ center field job on a permanent basis the following year.

“Willie can run as fast any anybody who ever put on a Dodger uniform,” Dodgers coach Clay Bryant told the Associated Press in Spring Training of 1961. “Two years ago when he came out of high school, all we could see was that he could run and had a fair arm. You wouldn’t believe the change. His arm is good now and he’s a good outfielder.”

Led by Maury Wills’ 104 stolen bases, Los Angeles stormed through the National League in 1962. Alston moved Davis into the No. 3 spot in the batting order in early May as Davis and Wills set the table for cleanup hitter Tommy Davis, who drove in 153 runs.

“He just outruns the ball,” Dodgers coach Joe Becker told the Associated Press. “When he learns how to get a jump on the pitcher, nobody will ever catch him. With his speed, he could break Maury Wills’ record.”

Willie Davis finished the season with a .285 batting average, 18 doubles, an NL-best 10 triples, 21 homers, 103 runs scored, 85 RBI and 32 steals.

But the Dodgers were unable to shake the Giants, who caught Los Angeles on the final day of the regular season – necessitating a three-game playoff to determine the pennant winner.

Davis went 0-for-8 at the plate as the Giants won Game 1 and Game 3, capturing the final game with a four-run rally in the top of the ninth.

But the young Dodgers core, featuring Tommy Davis, Willie Davis, Frank Howard and the incomparable Sandy Koufax, bounced back in 1963 to win the pennant and then sweep the Yankees in the World Series. Willie Davis saw his average drop to .245 but still drove in 60 runs and stole 25 bases – hitting a two-run double in the top of the first of Game 2 of the Fall Classic that powered Los Angeles to a 4-1 win and put the Dodgers firmly in control of the series.

Then in Game 4, Davis’ seventh-inning sacrifice fly scored Jim Gilliam to break a 1-1 tie as Koufax and Whitey Ford reprised their Game 1 battle. Koufax made the 2-1 lead stand up to give the Dodgers the title.

The Dodgers were unable to repeat as champions in 1964 largely due to injuries to Koufax, but Davis bounced back to his 1962 level of play with a .294 batting average, 12 homers 77 RBI and 42 steals to go along with an NL-leading totals of 404 putouts and 16 assists in center field.

“Sure I’d like to get in that big money class with Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle,” Davis told the Associated Press in Spring Training of 1965. “Who wouldn’t? But I’ve got a long way to go.”

Davis hit just .238 in 1965 but the Dodgers returned to the top of the National League.

In the World Series, Davis tied a mark with three stolen bases in Game 5 – something that had not been accomplished since Honus Wagner of the Pirates stole three bases in Game 3 of the 1909 World Series – as the Dodgers beat the Twins in seven games.

But after the Dodgers won another NL pennant a year later, the 1966 World Series would not be kind to Davis. In a scoreless Game 2 in the top of the fifth inning – with the Orioles having defeated Los Angeles in Game 1 – Davis was charged with three errors on two consecutive plays, dropping fly balls by Paul Blair and Andy Etchebarren and then allowing Blair to score on an errant throw to third base.

“I just lost them in the sun,” Davis told the Associated Press following the game.

Baltimore would go on to sweep the Dodgers.

With Koufax retiring following the 1966 season, the Dodgers fell to eighth place in 1967 as Davis hit .257 with 20 steals after missing 20 games after injuring his ankle in Spring Training. Davis fared better in 1968, stealing 36 bases and scoring 86 runs, good for seventh in the NL during the Year of the Pitcher.

Then in 1969, Davis suffered a hairline fracture of his right arm after getting hit by a pitch from Claude Raymond of the Braves during an exhibition game on March 29, 1969.

“This is pretty rough on Willie and the club,” Dodgers manager Walter Alston told the Associated Press after Davis suffered the broken arm.

When Davis returned in late April, he went into a prolonged slump and found himself hitting .256 on July 10. But in his final 74 games of the season, Davis found a hitting stroke that he had not seen since Triple-A in 1960. He batted .347 in that stretch with 20 doubles, recording a 31-game hitting streak from Aug. 1-Sept. 3 that was the third-longest in modern NL history. When he reached 30 consecutive games with a hit, he broke the Dodgers record set by Zack Wheat in 1916.

“They’re just (falling) in,” Davis told the Progress Bulletin in Pomona, Calif., during the streak. “But one change I have made is taking more time before I swing. (Dodgers coach) Danny Ozark told me is that the only time you should be quick is when the bat is swinging.”

Davis finished the season with a .311 batting average in 129 games and was given a pay raise from $55,000 to $70,000 for the 1970 season. He continued his fine work at the plate that year, leading the NL with 16 triples that season, hitting .305 and stealing 38 bases while leading all NL center fielders with a .991 fielding percentage.

Then in 1971, Davis was named to his first All-Star Game during a season in which he set career-highs in hits (198) and doubles (33) while winning his first Gold Glove Award on the strength of an NL-best 402 putouts in center field.

Davis was hitting .350 at the All-Star Break and finished at .309.

As Davis found his best self as a player in the early 1970s, the Dodgers were rebuilding a minor league system that would become the envy of almost every other team. But that work took years to bear fruit, as Los Angeles did not play a postseason game from 1967-73.

Davis won his second Gold Glove Award during the 1972 season, hitting .289 with 19 homers, 79 RBI and 20 stolen bases. He appeared just as strong as ever during his age-33 season a year later, hitting .285 with 16 homers and 77 RBI while winning his third straight Gold Glove and earning another All-Star Game berth in a year in which he was named team captain.

But on Dec. 5, 1973, the Dodgers traded Davis – whose 2,091 hits ranked third all-time in franchise history – to the Expos for pitcher Mike Marshall. Davis had requested a trade at the end of the 1973 season, reportedly because he was not getting along with Alston.

“We made the trade because we had the opportunity to acquire one of baseball’s best relief pitchers,” Dodgers general manager Al Campanis told the Los Angeles Times.

Davis, meanwhile, looked forward to the change of scenery.

“The Dodgers have always treated me first class, but I’ll definitely be trying to beat them next year,” Davis told the L.A. Times. “I may be leaving a contender, but I feel I’m going to another one.”

Davis continued his excellent play in 1974, hitting .295 with 12 homers, 89 RBI and 25 steals for a Montreal team that went 79-82. But Marshall proved to be the piece that put Los Angeles back in the postseason, working in a record 106 games while going 15-12 with 21 saves and winning the NL Cy Young Award.

One year to the day after the Dodgers traded Davis to the Expos, Montreal sent Davis to the Rangers in exchange for prospects Pete Mackanin and Don Stanhouse.

“At the close of the 1973 season, when we were close, we realized that there was just one more chance for us with veterans such as Ron Hunt, Ron Fairly and Bob Bailey,” Expos manager Gene Mauch told the Montreal Gazette. “We felt the acquisition of Davis might be just enough to complete the job. That didn’t materialize. So now we are going all the way with the younger players.”

The Rangers also hoped that Davis might help them reach the top, but he hit just .249 in 42 games before he was dealt to the Cardinals on June 4, 1975, in exchange for Ed Brinkman and Tommy Moore.

After he finished the season with a .277 average, 11 homers, 69 RBI and 23 steals for Texas and St. Louis, the Cardinals traded Davis to the Padres for outfielder Dick Sharon on Oct. 20, 1975.

But in 1976, age began to significantly erode Davis’ skills. In 140 games, he hit .268 but slugged just .375 with career full-season lows in home runs (five) and doubles (18).

On Jan. 22, 1977, the Padres released Davis. He spent the next two seasons in Japan, hitting 25 homers for the Chunichi Dragons in 1977 and batting .293 for the Crown Lighter Lions in 1978.

Then in 1979, Davis returned to North America, signing with the California Angels on March 27. Angels general manager Buzzie Bavasi, who had spent years with Davis with the Dodgers, brought the veteran outfielder in as a bench bat for a team that was expected to contend for the AL West title.

Davis appeared in just 43 games and hit .250, but the Angels won the division championship to advance to the postseason for the first time. In his final big league at-bat in Game 2 of the ALCS vs. the Orioles, Davis stroked a pinch-hit double and later scored on a Carney Lansford single – off Don Stanhouse.

Finding no big league offers for the 1980 season, Davis hit .301 in 91 games for Veracruz of the Mexican League.

In setting a since-broken Los Angele Dodgers record with 1,952 games played, Davis became an L.A. icon. He appeared in several television shows over the years, including Mister Ed and The Flying Nun.

Davis totaled 2,561 hits, 395 doubles, 398 stolen bases, 182 home runs, 1,217 runs scored and 1,053 runs scored. He was often criticized for his lack of plate discipline – and he drew just 418 career walks while compiling a .311 on-base percentage. But his all-around play is not lost on modern metric measurements, which tend to favor players with high on-base percentages. Davis remains the only player in history with a career WAR of at least 60 and an on-base percentage of less than .320.

He passed away on March 9, 2010.

“He was so talented,” Maury Wills told the Los Angeles Times following Davis’ death. “God really blessed him with some great tools – for any sport, really – speed, strength, agility – everything an athlete needs in order to make the big time.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum