- Home

- Our Stories

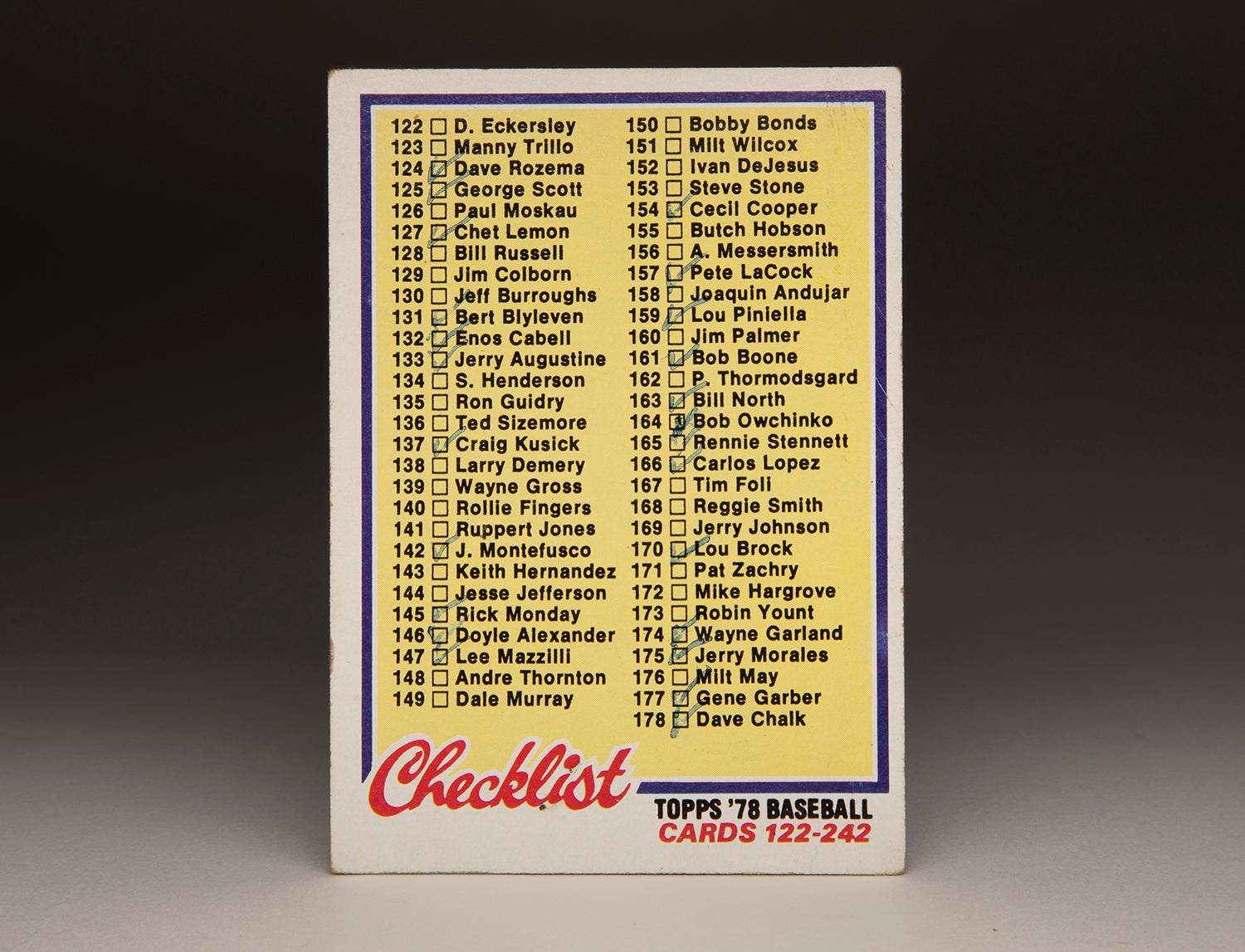

- #CardCorner: 1978 Topps Bruce Kison

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Bruce Kison

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

A baseball lifer named Bruce Kison recently passed away. He was a member of two world championship teams, a highly competitive pitcher, a knowledgeable coach, and finally, a highly respected scout.

Over a career that spanned nearly 50 years, Kison did nearly everything within the game.

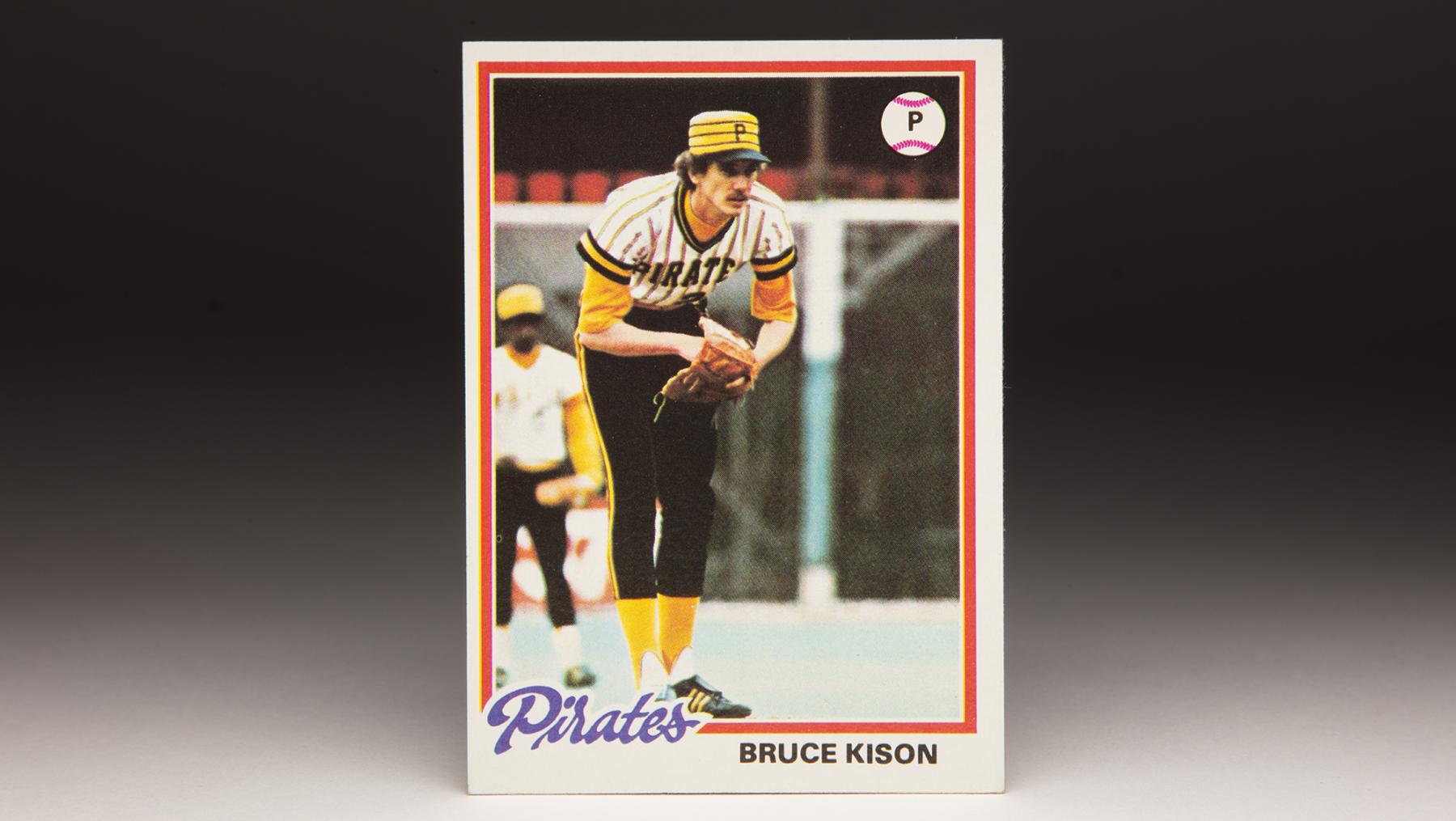

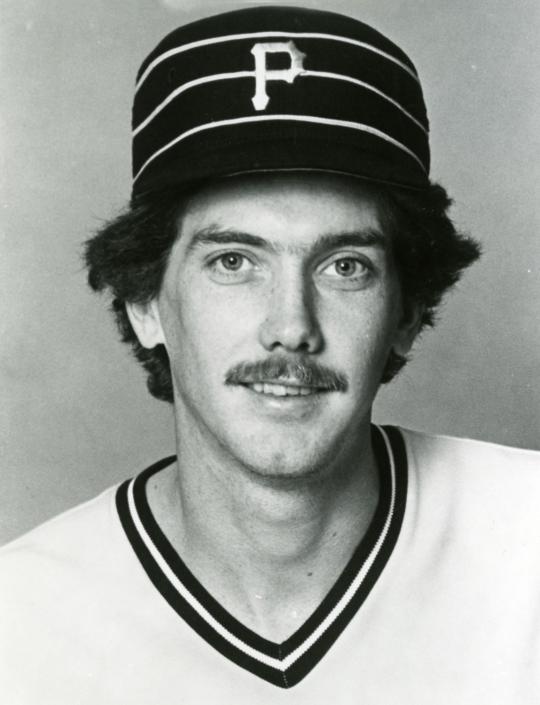

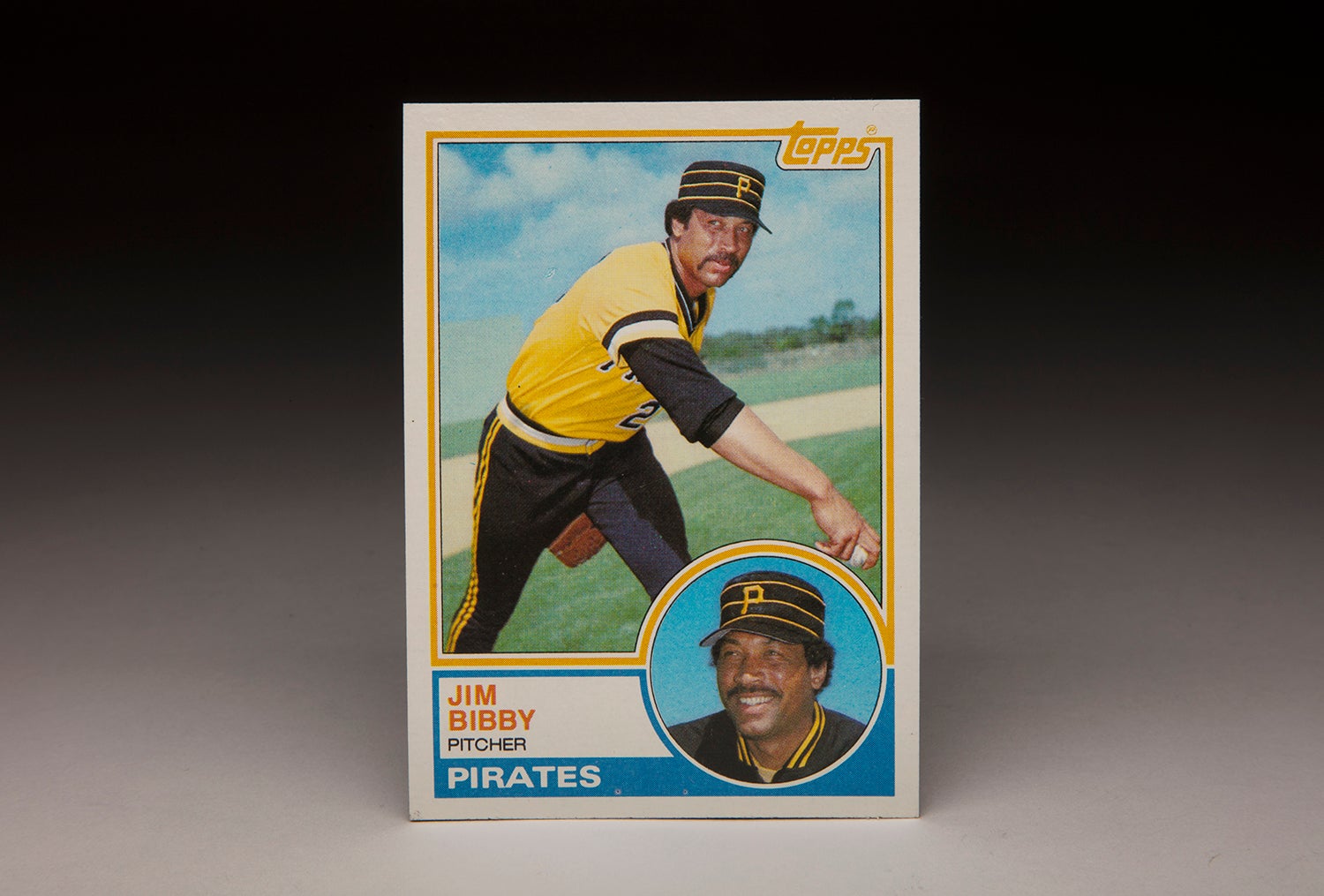

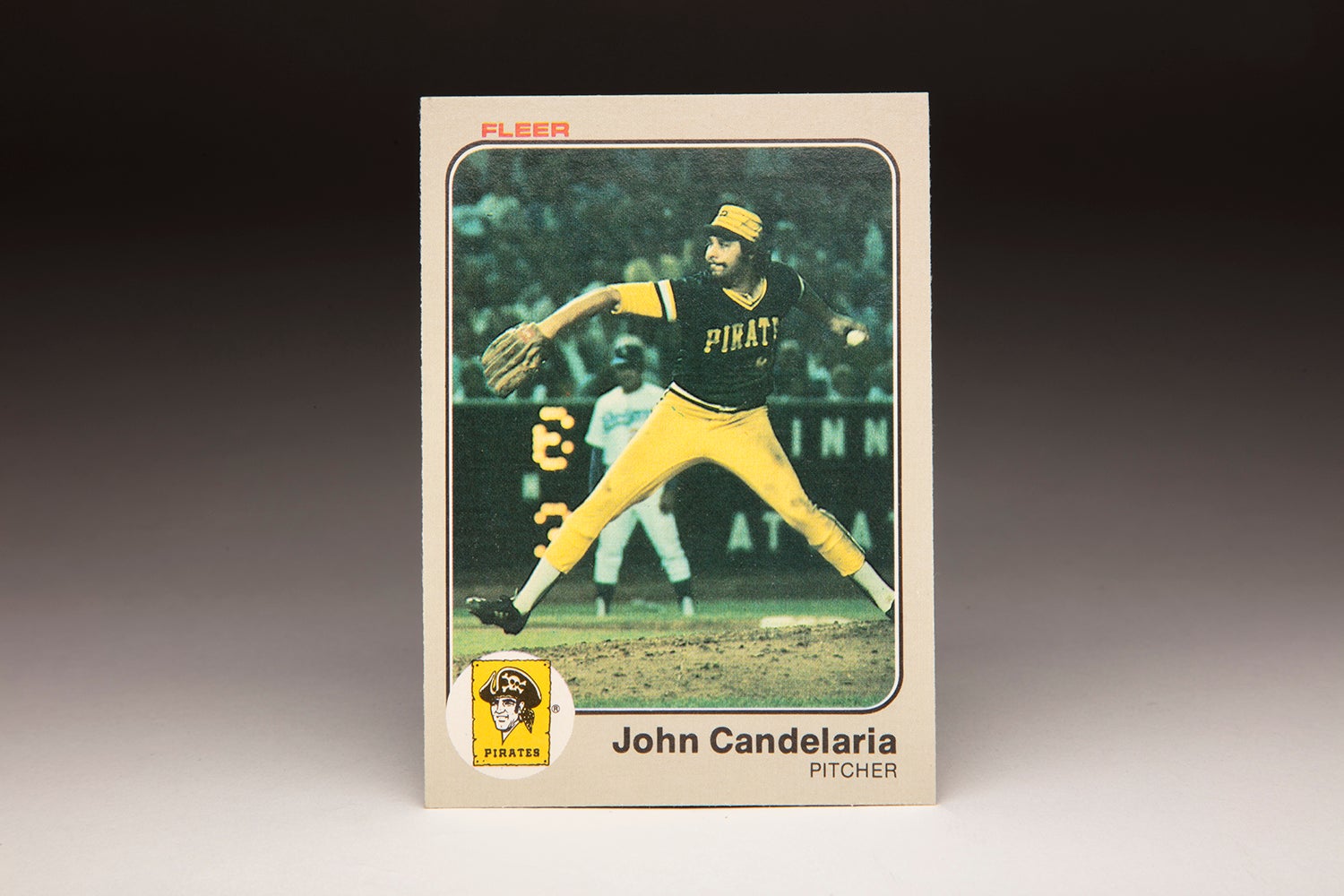

Of all of the jobs that he performed, Kison was best known for his work as a pitcher. Of all of his baseball cards, this one was my favorite: A classic piece from 1978 Topps. This is a card that almost perfectly embodies 1970s baseball. Like many players from the latter part of that decade, Kison sported a mustache; in his case, it covered up a baby face appearance that made him look like he should still be taking classes, not facing major league hitters. He also had a bushy head of hair, covered by that wonderful pillbox cap the Pittsburgh Pirates made famous.

On the whole, that Pirates uniform is simply fabulous. The horizontal lines of the gold cap clash with the vertical lines of the Pirates’ pinstriped jersey, which is accented by those three audacious black and gold stripes at the sleeves. Just when you’re overwhelmed by all of those vertical and horizontal stripes, the Pirates’ uniform then sends us in another direction, with a pair of jet black paints that give way to a set of bright gold stirrups. Could you imagine watching these Pirates in HD, with these gaudy double-knits leaping off a large screen and practically seeping into your living room? It’s enough to make you shudder.

So is the body language given off by Kison on his card. As gaudy and extreme as his uniform might be, Kison remains all business on the mound. Notice how he is hunched over, staring intently at his catcher to pick up the signal for his next pitch. This image is typical of Kison’s on-mound demeanor; he was as steely and resolute on the mound as any pitcher of the last 45 years.

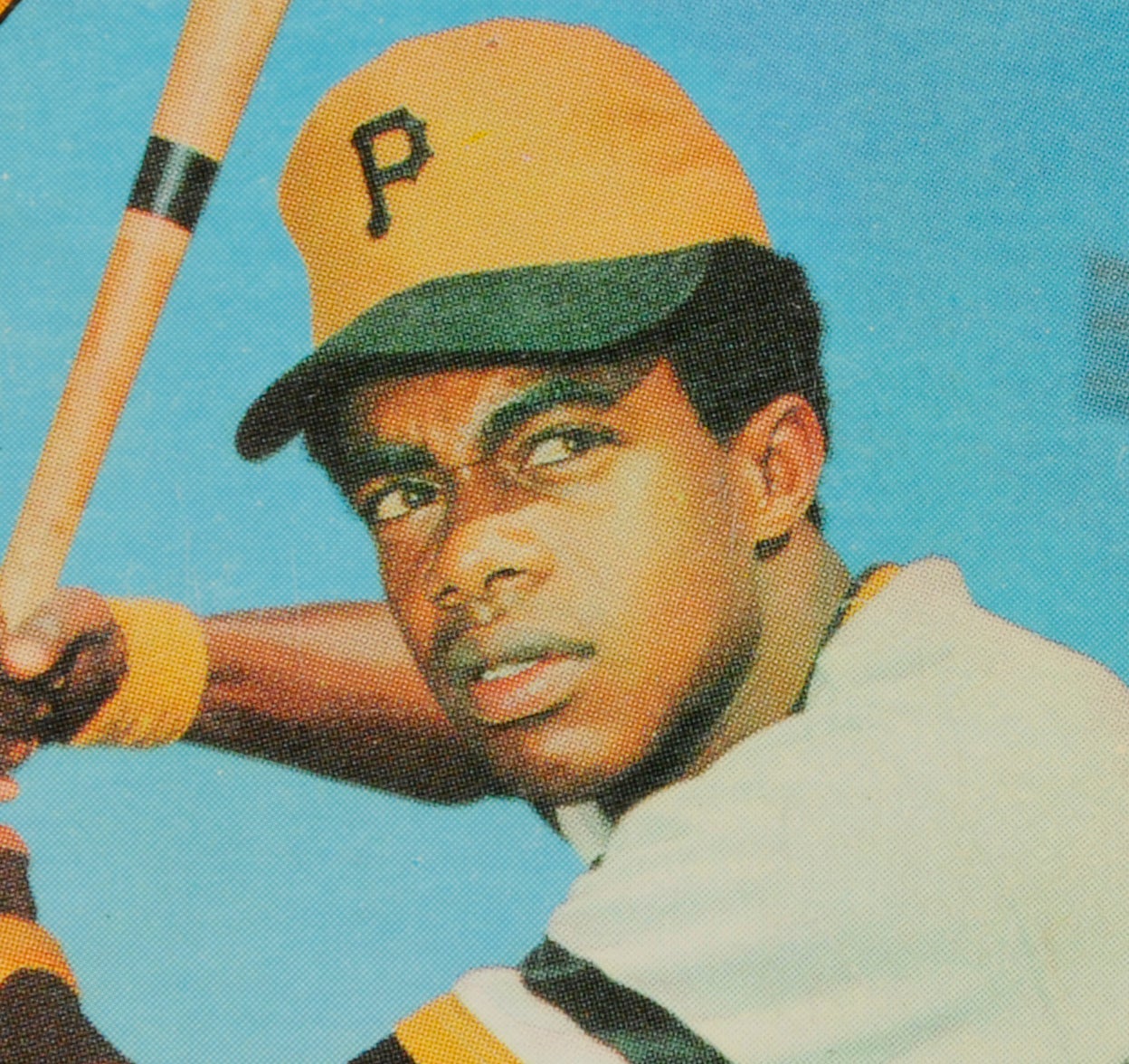

Kison’s 1978 card gives us an added bonus of a second player wearing these boldly beautiful polyester duds. From this angle, the Topps photographer has included the Pirates’ second baseman within his frame. There is an oddity here. The second baseman appears to have white stirrups, in contrast to Kison’s gold stirrups.

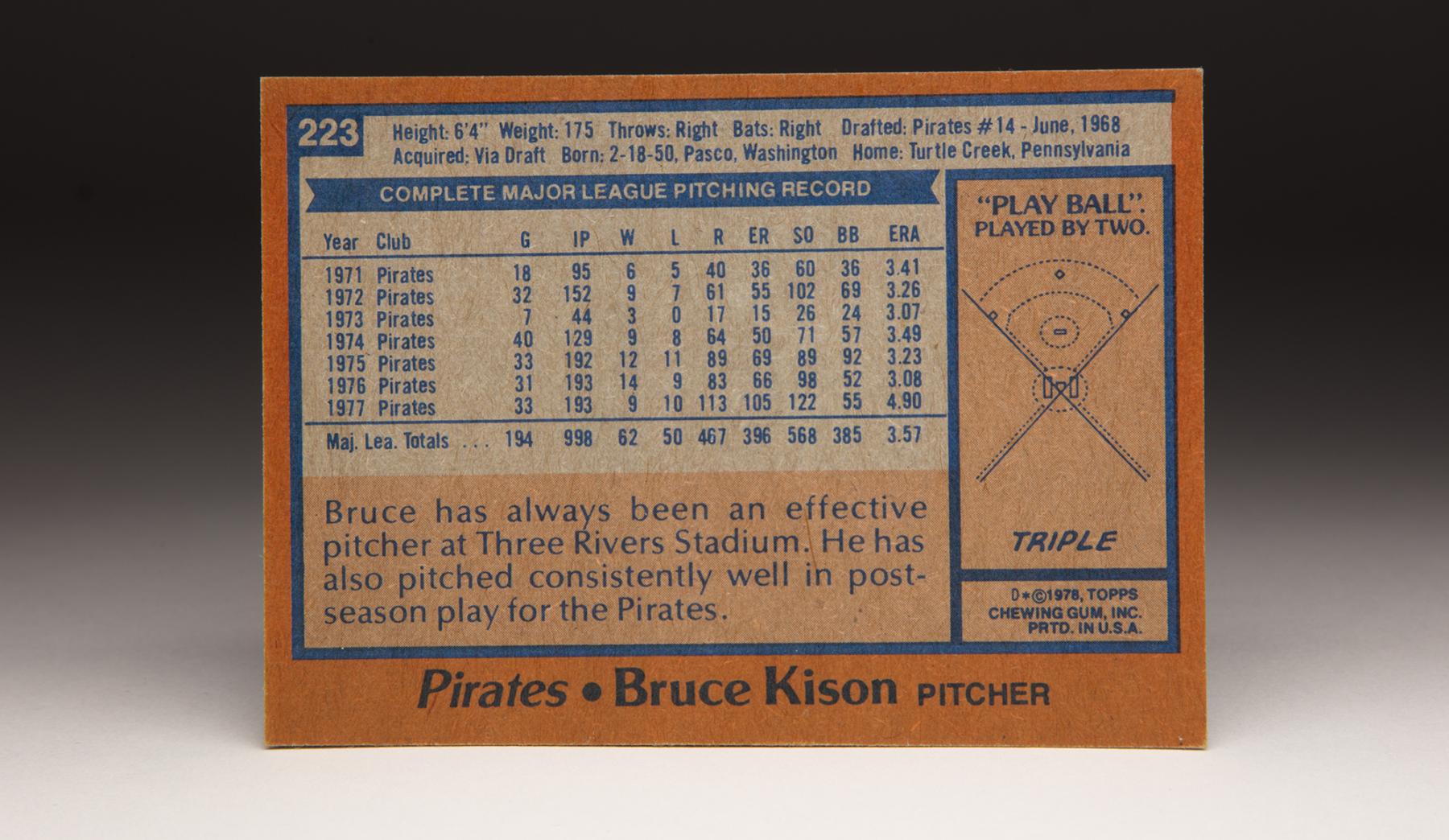

A more pertinent question is this: Who is this mystery second baseman? At first glance, it looks like Dave Cash, but that can’t be right; Cash played for the Pirates from 1970 to 1973, before being traded to the Philadelphia Phillies for Ken Brett. This photo was almost certainly taken during the 1977 season, so that rules out Cash. Who is it?

A logical guess would be Rennie Stennett, the Panamanian second baseman who succeeded Cash. I don’t remember Stennett having as large a head as the player in this photograph, but I could be wrong. Let’s use the background of the photograph to figure this out. Based on the artificial turf and the distinctive chain-link fence behind Kison, we know that this is Candlestick Park in San Francisco. Kison appeared in two games at Candlestick that summer. One of the games was Aug. 31, a day game. The Pirates’ second baseman that day was Phil Garner. I’m sure of few things in life, but I am certain that is not Phil Garner in the photograph.

The other game was on June 18, also a day game. A check of the boxscore reveals that Stennett played the entire game at second base. So my memory was wrong; it is Stennett after all. Coincidentally, Stennett has the greatest season of his life in 1977, when he batted .336, stole 28 bases, played a dandy second base, and earned some support in the MVP vote. On his way to becoming the best second baseman in the National League, Stennett appeared to be headed toward stardom. But his season ended prematurely; on Aug. 21, in a game against the Giants no less, Stennett awkwardly slid into second base, dislocating his ankle. The injury forced him onto the disabled list for the rest of the summer and permanently affected his play. Stennett would go on to have a decent career, but his chances of becoming a perennial All-Star had ended.

Stennett’s career would provide interesting fodder for an entire CardCorner, but it is Kison who occupies most of our attention on this card. For a few years, Kison’s name occupied the attention of young fans like me growing up in Westchester Country. We thought his name was pronounced KISS-on, which immediately brought snickers to our childish faces. It took a while for us to realize that his name was pronounced KEE-sun, which wasn’t nearly as funny.

Kison’s professional career began 10 years before his 1978 Topps card came out; he was taken in the 14th round of the 1968 MLB Draft. Some scouts were wary of Kison, mostly because of his strange sidearm delivery, which he resorted to in his youth, after being hit in the elbow on a pickoff attempt. Preferring young pitchers with more traditional motions, the 24 major league teams bypassed Kison for 13 rounds.

Even after that injury, Kison threw hard, and his sidearm motion added movement to his pitches. Initially assigned to Bradenton of the Gulf Coast League, Kison received early lessons in pitching from Harvey Haddix, the onetime Pirates pitcher who was now a minor league coach. Of all of Kison’s coaches, none would have more influence than Haddix.

After a good year with Geneva of the NY-Penn League in 1969, Kison moved on to Class A Salem and Double-A Waterbury in 1970. He pitched well, but also made a few headlines by hitting 28 batters with pitches. Wildness had little to do with the hit-by pitches; Kison loved to pitch inside and felt that hitters were fair game if they leaned into the strike zone. Dominating and intimidating the opposition at both levels, he moved up to Triple-A Charleston to start the 1971 season. Kison wouldn’t have to stay long at Charleston. He overpowered hitters in Triple-A, posting an ERA of 2.86 and winning 10 of his 12 starts.

In early July, the Pirates called Kison up to replace Bob Moose, who was serving a two-week stint in the Army Reserves. (Such military duty was common during the era of the Vietnam War.) Kison made his debut on the Fourth of July. Given a start against the Chicago Cubs, Kison lasted six innings, allowing four runs. It was a lackluster performance for the skinny right-hander, who stood 6-foot-4, weighed all of 165 pounds, and looked like he still belonged in high school.

In his next three starts, Kison showed that he belonged in the major leagues, not on a high school field. He shut down Los Angeles, San Diego, and Cincinnati in succession, allowing only two combined runs over 23 innings. Kison would spent most of the remaining summer in the rotation, but would also make five relief appearances as part of Danny Murtaugh’s interchangeable staff of pitchers. Pitching to the tune of a 3.40 ERA, the versatile Kison gave the Pirates valuable innings as they marched toward the National League East title.

While the ’71 Pirates featured headline names like Roberto Clemente, Willie Stargell and Dock Ellis, Kison would make a name for himself during the World Series. With the Pirates trailing the Baltimore Orioles, two games to one, the two clubs prepared to play the first night game in World Series history. It was practically a must-win situation for the Pirates, who fell behind in the first inning, 3-0, forcing Murtaugh to pull his starter, Luke Walker.

Murtaugh summoned the 21-year-old Kison, who ended the Orioles’ rally and proceeded to pitch shutout ball over six and two-thirds innings. In the meantime, the Pirates rallied to tie, eventually taking the lead. The Pirates won the game, 4-3, with Kison earning his second victory of the postseason.

The game did not come without controversy. After reaching base and running toward second base on a potential double play ball, Kison opted not to slide, and awkwardly collided with Orioles second baseman Dave Johnson. After the game, Orioles veteran Frank Robinson was asked to assess Kison’s pitching but instead offered the rookie some unsolicited advice. “I think he’d better learn to slide,” Robinson told Gannett News Service. “I’ve never taken an infielder out like that since I’ve been playing.”

Kison claimed that he done nothing wrong, but the controversy died down quickly amidst the close, dramatic nature of the Series. After the Pirates won a dramatic Game 7, Kison made headlines of a different sort. He had little time to celebrate the world championship; that’s because he was set to get married that night. Months earlier, Kison had planned his wedding for that night, not knowing that the Pirates would be in the World Series and not knowing that he would even be with the team.

Longtime Pirates broadcaster Bob Prince arranged for a helicopter to pick up Kison and his best man, fellow right-hander Bob Moose, at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium and take them to the local airport. From there, Kison and Moose boarded a private Lear jet, set for a direct flight to Pittsburgh. That evening, Kison married Anna Marie Orlando, completing the best 24 hours of the young right-hander’s life.

In 1972, Kison showed no signs of a sophomore slump, despite starting the season on the disabled list with a sore shoulder. Kison returned from the DL shortly thereafter and pitched well, even with persistent pain. Once again used as both a starter and reliever, Kison won nine games, struck out 102 batters in 152 innings, and again helped the Pirates win the divisional title. Kison would make two appearances in the NLCS against Cincinnati, keeping the Reds scoreless each time, but the season would end in heartbreaking fashion, the Pirates falling to the Reds in the ninth inning of a decisive Game 5.

The pain in Kison’s shoulder remained, even after a winter of rest. Kison started the season on the disabled list. When the Pirates deemed him healthy enough to pitch, they assigned him to Triple-A Charleston, where wildness plagued him throughout the summer. In 114 innings, he walked 82 batters and uncorked 11 wild pitches. In spite of such erratic pitching, the Pirates called him up in September. Kison’s control remained spotty, but he otherwise pitched well, winning three games, losing none, and posting an ERA of 3.09.

After the season, the Pirates assigned Kison to the Florida Instructional League to work with former major league pitching coach Don Osborn. Under the watchful eye of the venerable Osborn, Kison made two changes: He altered his delivery to a three-quarters motion and underwent a weightlifting program, meant to strengthen his upper body and shoulder.

The alterations to Kison’s regimen worked. In 1974, he came to Spring Training pain free, a direct contrast to the previous two springs.

Used out of the bullpen for most of the season by Murtaugh, Kison appeared in a career-high 40 games and logged 129 innings. Murtaugh then called on Kison to start Game 3 of the NLCS; Kison responded by shutting out Los Angeles for the first six and two-thirds innings and picking up another postseason victory.

In 1975, Murtaugh returned Kison to the starting rotation, where he would remain for the next three seasons. Over that span, Kison logged more than 190 innings each summer, pitching effectively in ’75 and ’76 before suffering a downturn in 1977. Injuries bothered Kison during that latter season, as a groin pull and persistent blisters left him compromised.

It was also during that 1977 season that Kison enhanced his reputation for a willingness to back off hitters. On July 8, Kison nailed Philly’s Mike Schmidt with an inside fastball, sparking a nasty bench-clearing brawl. It was no wonder that Kison, despite his baby-faced look, was now known by the nickname of “The Assassin.”

After the 1977 season, Kison’s status as a fulltime member of the rotation changed. The Pirates acquired Bert Blyleven in a three-way trade with the Texas Rangers, a move that bumped Kison into the bullpen. Kison would make only 11 starts during the season, instead spending most of the summer in long relief.

As the Pirates headed to Spring Training in 1979, rumors circulated that Kison might be traded. But then came an injury to the newly acquired Rick Rhoden, opening up a temporary spot in the rotation for Kison. He pitched well in his first start, went to the bullpen for three weeks, and then returned to the rotation on June 3, when he pitched a one-hitter against the San Diego Padres. From that point, Kison became a full-time starter. He pitched beautifully in 1979, winning 13 games and spinning an ERA of 3.19. Part of an unheralded Pirates staff, Kison became a huge factor in the Pirates winning the National League East.

The postseason did not go as well for Kison. After being bypassed in the NLCS, he started Game 1 of the World Series. It was a cold October night in Baltimore, with the temperature reading 41 degrees. Unable to warm his arm, Kison felt numbness and lasted only a third of an inning, surrendering four earned runs. The Pirates would rally to win their second championship of the decade, and earn Kison a second World Series ring, but the resilient right-hander had pitched his final game as a Pirate.

Now eligible for free agency, Kison cashed in. At one point, it seemed like he was headed for the New York Yankees – the New York City newspapers declared it a done deal – but he instead took a five-year deal worth $2.5 million from the Angels. The Angels struggled with free agency during the late 1970s and early 1980s, with many of their big name signings turning into busts. Sadly, Kison felt into that category.

He started the 1980 season poorly before being diagnosed with a bad ulnar nerve in his right elbow. The Angels shut him down in the middle of July and arranged for season-ending surgery. Doctors warned Kison about the perils of the dangerous operation to the ulnar nerve. The surgery left Kison without feeling in three of his fingers. At times, he couldn’t move his hand. Feeling guilty about his huge contract, the prideful Kison offered to give the Angels a refund of at least part of his salary, but general manager Buzzie Bavasi turned down the offer.

Several writers predicted that Kison would never pitch again. Losing none of his determination, Kison underwent a grueling rehabilitation process and defied the skeptics. On Aug. 10, 1981, Kison returned to the mound with a relief appearance against Seattle. Remarkably, he even made four starts for the Angels during the stretch run. Over 44 innings, Kison posted a highly respectable 3.48 ERA.

In 1982, Kison moved into the Angels’ rotation and pitched well until being hit in the shin by a Johnny Grubb line drive. As the Aug. 31 trading deadline approached, rumors indicated that Kison might be traded to the Yankees, who remained interested after losing out on him in free agency. Instead, Kison remained with the Angels, returned to the rotation, and dominated the month of September, continuing a career-long trend.

For the season, Kison won 10 games and helped the Angels win the West. He made two effective starts against Milwaukee in the ALCS, enhancing a reputation as a clutch pitcher. It was no wonder that Peter Gammons and Bill James would describe Kison as one of the best big-game pitchers in history.

Kison’s stretch of good pitching continued early in 1983, but a back injury ruined his run of success. In September, he underwent lumbar surgery. Once again, doctors warned him that the procedure could end his career. Remarkably, Kison fought his way back again. Less than a year later, he returned to the mound. Unfortunately, the complicated back surgery left him a shell of his former self. His ERA of 5.37 convinced the Angels to let him become a free agent.

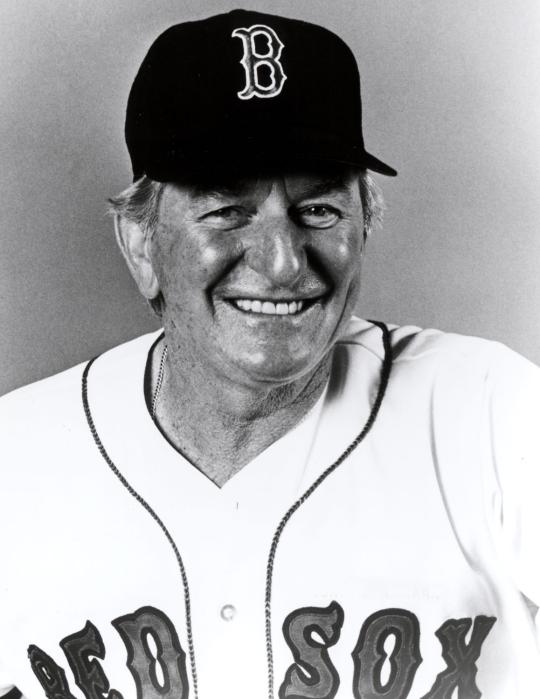

In January of 1985, Kison found work with the Boston Red Sox. Used mostly as a reliever, Kison didn’t pitch particularly well for the Red Sox, but his status as a leader impressed the organization. Manager John McNamara, who had also managed Kison with the Angels, praised the veteran for his influence on young pitchers like Roger Clemens, Bruce Hurst, and Bobby Ojeda. “A tremendous competitor,” McNamara once told Larry Whiteside of the Boston Globe. “And a heck of a pitcher. He did everything I asked him to do, both here and at California.”

After the season, doctors diagnosed Kison with a torn rotator cuff. Facing another long rehab process, which would have been his third, Kison opted to retire. Only two years later, he returned to the Pirates as a roving instructor. From there, he moved on to Kansas City’s minor league organization; one year later, the Royals promoted him to the major league staff, first as a bullpen coach and then as pitching coach. He eventually became a pitching coach with the Orioles, who then moved him into a scouting position, where he remained for more than 10 years.

Kison decided to retire in December of 2017. Two months later, he came down with severe back pain, which was diagnosed as bone cancer. By June, he lost his fight. Kison, who was only 68, left behind his wife Anna, the same Anna who had married him on the night of the World Series. Tributes poured in for Kison, even if he had made a few enemies over the years because of his willingness to “throw inside.” The hitters who played pin cushion to Kison were far outnumbered by his fans and friends. Those who remembered Kison were far more interested in his endless streak of competitiveness, his old school knowledge, his ability to teach and his perpetual love of the game. Kison was a baseball lifer, and for those who follow the game, there is no higher compliment than that.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital & outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum