- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1983 Fleer John Candelaria

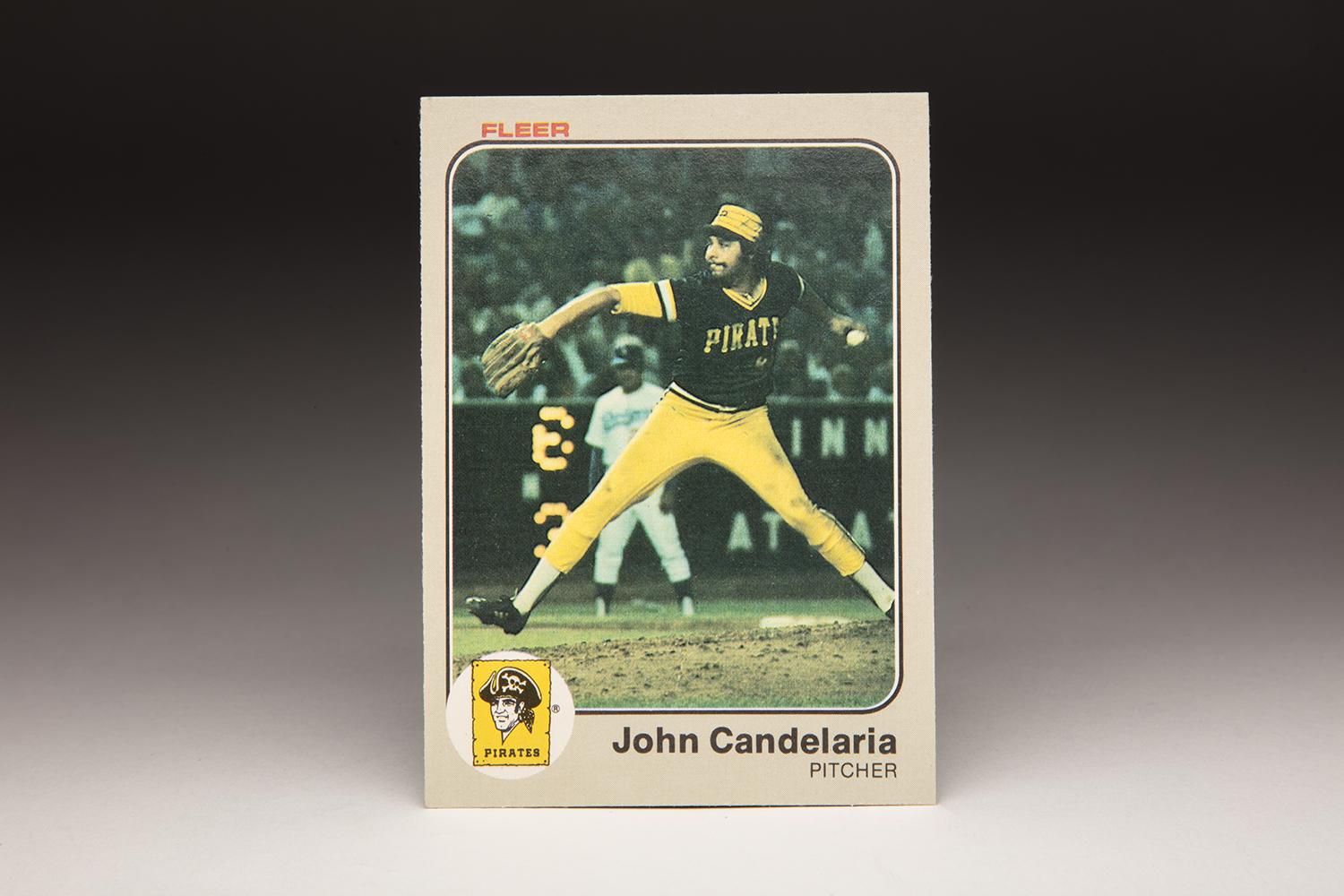

#CardCorner: 1983 Fleer John Candelaria

Nineteen eighty three was a very good year for baseball cards. All three of the companies that had licensed agreements with Major League Baseball produced solidly attractive sets that spring and summer.

The Topps Company, for the first time since 1963, featured two photographs on the front of its cards. Donruss, one of the Topps’ challengers, came out with a catchy design featuring a baseball bat, along with clear photography that was a major improvement over its first two sets. And then there was Fleer, which came out with a set that has received little attention, but has become one of my favorite sets of the 1980s.

The Fleer set gave us a different look because of its unusual border. Rather than use the standard white border, or even the black border that Topps had dabbled with in 1971, Fleer produced cards with a subtle-but-pleasing gray border that was highlighted by the team logo in the lower left-hand corner. The set featured a nice mix of action, posed, and portrait shots, giving the set a good level of variety. The photography, while spotty at times, provides us some examples of action shots taken from unusual angles. Clearly, Fleer was willing to try something different with the third set that it produced after the federal court ruling that had ended the days of the Topps monopoly.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

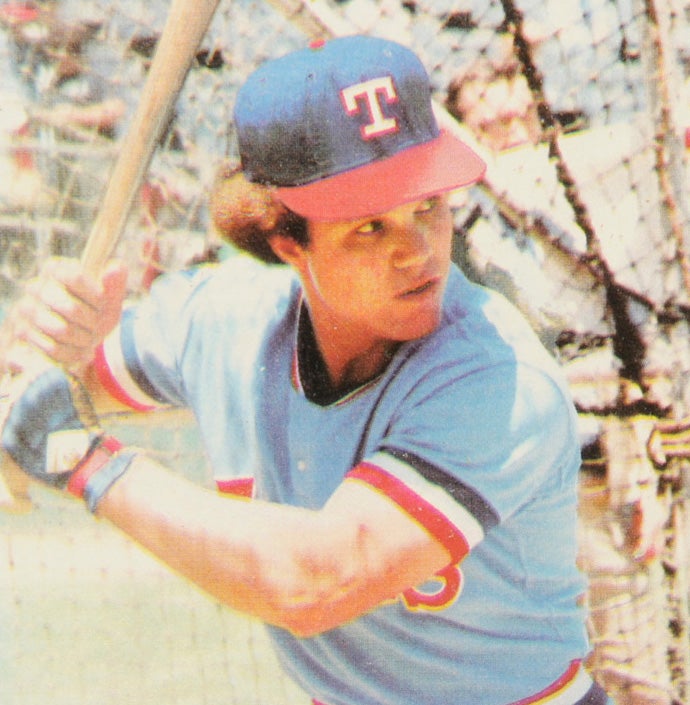

Fleer’s 1983 card of John Candelaria stands out for several reasons. First, it gives us a full view of the Pittsburgh Pirates’ memorable “bumblebee” uniforms of this era, in this case, the black top with the gold (or yellow) pants. (The Pirates used the mix-and-match black and gold from 1977 until 1984.) Also evident is the Pirates’ pillbox cap, first introduced by several National League teams in 1976 (as a celebration of the NL’s centennial) and continued by the Pirates through the 1986 season.

Second, the action shot of Candelaria is interesting for two distinct reasons. While most action shots tend to be photographed in the daytime, this is clearly a shot from a night game, one that took place at Dodger Stadium. The photograph, taken from the perspective of the first base dugout, gives us a clear view of Candelaria’s distinctive motion. At 6-foot-7, Candelaria was one of the tallest pitchers of his era. As such, he had a very long stride toward home plate. With his front foot about to land near the front of the mound, Candelaria appears ready to release the ball from a point located at least a couple of feet in front of the pitching rubber. Thanks to his long legs and arms, and unusual three-quarter delivery that sometimes became a full sidearm, it’s painfully obvious why Candelaria gave so many hitters fits during his prime years in the 1970s and 80s.

There are a couple of other interesting footnotes to the card. The third base coach seen in the background is Danny Ozark, formerly the manager of the Philadelphia Phillies before becoming one of Tommy Lasorda’s lieutenants in LA. It’s also worth noting that Candelaria did not pitch at Dodger Stadium in either 1982 or 1981, so we can surmise that this photo is from a game in 1980 – three years before the release of the card. The game likely took place on May 16 of that year, a Friday night game in which Candelaria squared off against another accomplished left-hander, Jerry Reuss. Candy was effective that night, giving up only one earned run in six and a third innings, but had to settle for a no-decision as the Pirates’ bullpen blew up in an 8-6 loss to the Dodgers.

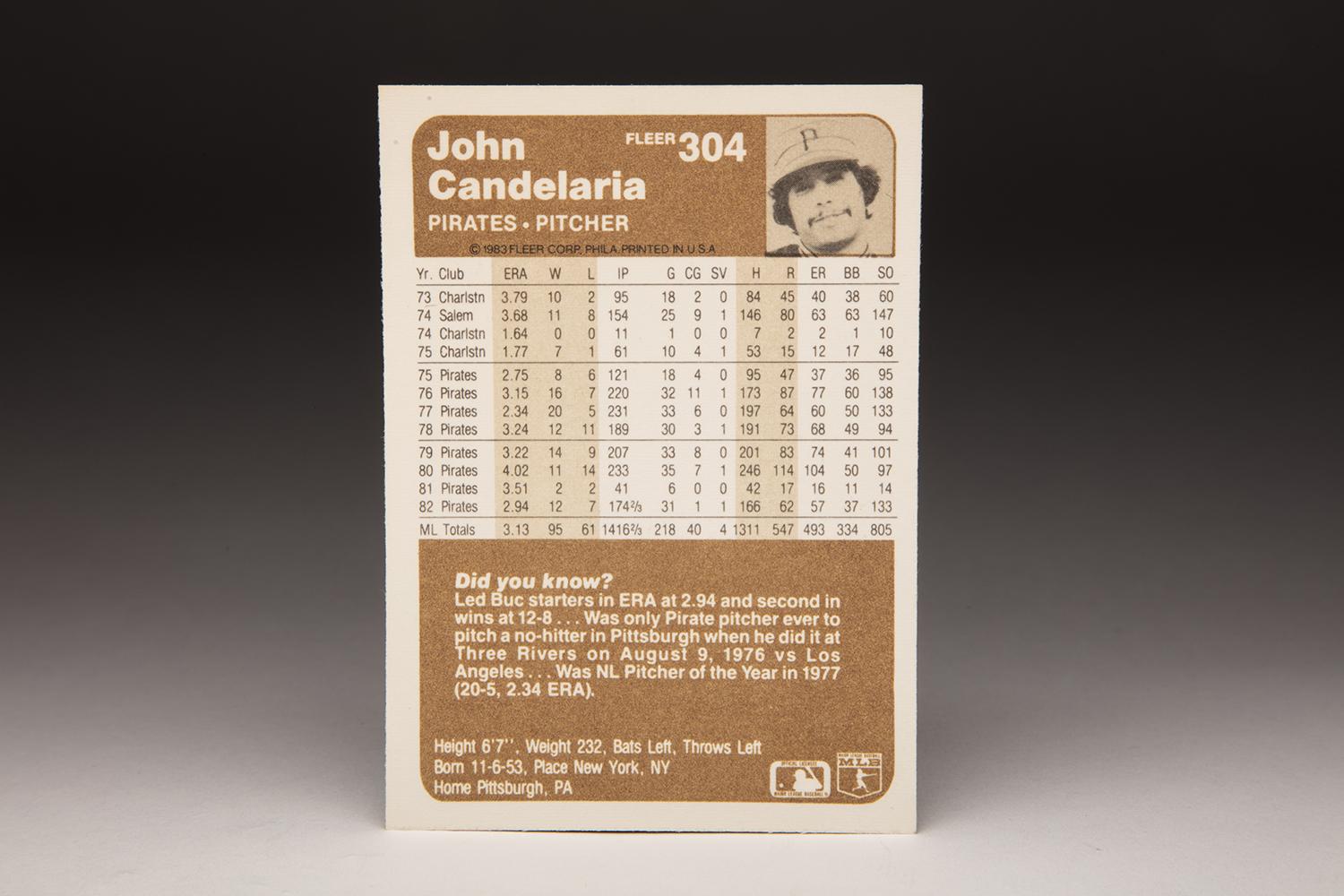

Good outings by Candelaria became a common occurrence for the Pirates. Selected by the Bucs in the second round of the 1972 draft, the native of New York City moved quickly up the minor league ladder and made his Pirates debut in 1975. Inserted immediately into the Bucs’ rotation, Candelaria won 8 of 14 decisions, spun an ERA of 2.76, and struck out 95 batters in 120 innings. Right from the start, Candelaria impressed the Pirates with his moving fastball and his evasive curve ball.

In 1976, Candelaria put in his first full season with the Pirates. He made 32 starts, won half of them, and logged 220 innings. The highlight of his season occurred on Aug. 9, when he faced the Dodgers. Throwing a total of 101 pitches, Candy pitched a no-hitter that night, impressive under any circumstances, but especially noteworthy because of the strength of the Dodgers’ lineup. The 1976 Dodgers, on their way to 92 victories, put out a lineup that included accomplished hitters like Davey Lopes, Steve Garvey, Ron “The Penguin” Cey and Bill Buckner, but none could muster a hit against the sidewinding Candelaria.

Candelaria flashed brilliance in that game against the Dodgers, but the next season, he would sustain excellence over an entire season. The 1977 season represented Candelaria’s coming out party. Despite a sore back that he developed in July, he won 20 games against only five losses, led the league with a 2.34 ERA, and logged 230 innings. Not only did he make the All-Star team, but he placed fifth in the Cy Young balloting. Some observers felt he should have placed higher in the balloting, but the voters showed a preference for more experienced starters like Steve Carlton, Tommy John, Rick Reuschel, and Tom Seaver, each of whom also won 20-plus games.

Although Candelaria was still only 23 years old, he would never quite match the heights of that 1977 season. The following spring, he reported to the Pirates’ camp having lost 20 pounds, which he hoped would result in his back feeling better. It did, but he developed a sore elbow and pitched at a significantly lesser level. Still, he won 12 games with an ERA of 3.24. He delivered more of the same in 1979, the year in which the Pirates won the division, the pennant, and the World Series. He was effective in one playoff start before struggling in Game 3 of the World Series. Given a 3-0 lead, Candelaria could not protect the margin, instead taking the loss. But in Game 6, he proved masterful, delivering six shutout innings, as the Pirates evened the Series at three games apiece. One day later, Candelaria and the Pirates emerged as world champions.

Candelaria suffered a downturn in 1980 and missed the majority of the ’81 season after developing nerve problems in his throwing shoulder. Injuries would become a recurring theme in his career. With his unusual pitching motion, in which he slung the ball from a three-quarters angle (somewhat like Andrew Miller of the Cleveland Indians today), he seemed to put extra strain on his left shoulder.

No longer able to pitch complete games on a consistent basis, Candeleria became a six- to seven-inning pitcher. But he was a good one. Over each of the next three years, he won in double figures, made at least 31 starts a summer, and generally assumed the role of staff ace. Nicknamed “The Candy Man,” he also become known as something of a free spirit. On one occasion, he was arrested by police for roller skating on the highway. As Candy once said, “Life is a mystery to be lived, not a problem to be solved.”

The outspoken Candelaria also battled the front office, as he attempted to negotiate better contracts for himself. At one time, he called the Pirates’ general manager a “bozo,” which did not ingratiate him with management. Despite the name-calling, Candelaria signed a four-year contract with the Pirates.

In 1985, Candelaria and the Pirates hit rock bottom, but for different reasons. On the prior Christmas Day, Candelaria’s son had been found unconscious in the family swimming pool. The boy, who was not even two years old, remained in a coma for most of 1985, before passing away in November. Understandably, the situation troubled Candelaria throughout the season. He came to look at baseball as a distraction from the harsh realities of his private life.

In the meantime, the Pirates’ franchise was rocked by the ongoing Pittsburgh drug trials. Looking to rebuild the team, general manager Harding “Pete” Peterson made a series of trades in which he disposed of veteran players in exchange for younger talent. One of those deals was completed on Aug. 2, when the Pirates traded Candelaria, who had been moved to the bullpen and had repeatedly requested a trade, along with fellow left-hander Al Holland and veteran outfielder George Hendrick. The three veterans went to the California Angels for a trio of younger players.

Though still upset by the situation involving his son, Candelaria took well to the American League. Returned to the starting rotation by manager Gene Mauch, Candelaria won seven of 10 decisions and stabilized the Angels’ rotation, while drawing the praises of teammate Reggie Jackson.

“Candelaria gives us a guy who can throw a shutout and dominate a game,” Jackson told veteran sportswriter Joe McGuff. “He’s our answer to [Kansas City Royals ace Bret] Saberhagen.”

The Angels would fall short of their goal of catching the Royals and winning the West, settling for a second-place finish, but Candelaria certainly did his part.

Returning to the Angels in 1986, Candy had to be shut down when bone spurs were found in his elbow, necessitating surgery. He missed three months of the season, but after his return, he pitched brilliantly, winning 10 of 12 decisions and forging an ERA of 2.55. In 1987, Candelaria’s arm felt fine, but he struggled with personal problems, specifically drinking. On two separate occasions he was arrested for driving under the influence. In June, the Angels placed him on the disabled list so that he could enter an alcohol rehabilitation facility.

By August, Candelaria was ready to return to the Angels, but his days in Anaheim were numbered. A month later, the Angels traded him to the New York Mets, who were desperately trying to win the National League East and had lost Ron Darling to injury. The news of the trade to New York thrilled Candelaria, who had grown up in Brooklyn. “Any kid who has played ball on the streets of Brooklyn or any of the other boroughs of New York dreams of playing for the Yankees or the Mets, and I was no exception,” Candelaria told Doug Gould of the New York Post.

As much as the trade elated him, Candelaria pitched poorly in three starts for the Mets. Still, he won two of the starts, but the Mets settled for second place in the Eastern Division. Now a free agent, Candelaria received several offers from teams, but first wanted to tackle a personal problem that had plagued him for years. Candelaria checked himself into an alcohol rehabilitation facility. After completing the initial treatment, he opted to sign with the crosstown Yankees, who needed pitching badly.

Candelaria reported to Spring Training with a positive frame of mind, determined to bring to a stop his tendency to make controversial comments and hoping to find some fun in the game. He also liked his new manager, Billy Martin.

Unfortunately, Martin did not last the season in New York. After the Yankees’ first 68 games, Martin was fired and replaced by Lou Piniella. Almost immediately, Candelaria clashed with his new skipper. The two men argued repeatedly over pitching philosophy. Candy also butted heads with Yankee catcher, Don Slaught. When he pitched, the 34-year-old left-hander delivered the goods – 13 wins and an ERA of 3.38 – but his season ended abruptly in August when he came down with knee pain. The Yankees felt that Candelaria could pitch through the pain, but the veteran left-hander felt otherwise. “Right now, I’m going home to California and I don’t expect to be coming back,” Candelaria told Bill Madden of the New York Daily News.

The Candelaria of old, a pitcher capable of logging 200 innings, might have pushed the Yankees into contention. But without Candelaria over the final two months, New York had to settle for also-ran status in a stacked Eastern Division.

The 1988 season turned out to be the last hurrah for The Candy Man. He missed most of 1989 with arm woes; after he returned, the rebuilding Yankees sent him to the Montreal Expos for third base prospect Mike Blowers. Candelaria spent most of the balance of his career pitching out of the bullpen, with varying degrees of success, as he bounced from Montreal to Minnesota to Toronto to Los Angeles before finishing his career back in Pittsburgh. A poor performance for the Pirates in 1993 convinced Candelaria to retire at the age of 39.

Candelaria left the game for good, never to work as a coach or a scout. For a while he owned an advertising agency in Pittsburgh, but he did not particularly like that line of business. He now lives a quiet life in North Carolina, and also enjoys traveling to foreign countries.

Ever since his playing days, Candelaria has heard the refrain that he never quite lived up to his potential. He has always bristled at that talk, believing that he had a successful career, as evidenced by his 177 wins during a career that lasted 19 seasons. He also won a world championship with the Pirates in ‘79. Perhaps his career might be a case of “not living up to potential,” but for those of us who have dreamed of playing even one day in the major leagues, it’s still pretty darned good.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame