- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1978 Topps Eric Soderholm

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Eric Soderholm

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Why is it that we like certain players over others? This is a question that I have long considered – and long found mystifying.

Perhaps the player is a particularly exciting type who plays for our favorite team. That certainly makes sense. Or maybe we find out that we have something in common with a player. For me, that latter reason helps explain why Roberto Clemente has always been a player to draw my interest. When I found out that Clemente was Puerto Rican, that struck a chord with me; my mother was Puerto Rican, having been born in Santurce, which just so happened to be the first professional winter league team with which Clemente played. Small world.

In other cases, the reasons for liking a player are less tangible. As an example, I’ve grown interested in the career of Tommy Davis, perhaps in part because he played for so many teams. For some reason, that makes him interesting to me. I guess I’ve always liked journeyman players who were good players, but clearly not stars or superstars. There’s just something about the everyday struggles of the so-called “common” player that resonates with me.

For many of these players, little about the game comes easy; yet somehow, they manage to persevere and find success.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Another player who would fall into this category for me is Eric Soderholm. It’s hard to pin down exactly why I liked Soderholm, but I did. When he was healthy – which was often a big “if” with Soderholm – he was a very good hitter and a solid defensive third baseman.

Perhaps I took an interest in him because of his ability to come back after missing an entire season to injury. Of course, it helped matters when he joined the New York Yankees later in his career. As a young Yankee fan, I often became infatuated with players who came from other teams and then helped the Yankees win. In particular, Soderholm became an important part of the 1980 Yankees, a team that I really enjoyed following, even if they ended up getting swept in the American League Championship Series.

In researching Soderholm, I’ve come to like him even more. As a player in Chicago, he gained some notoriety for his interest in writing poetry. Highly intelligent and thoughtful, Soderholm has become hugely successful in his post-playing career.

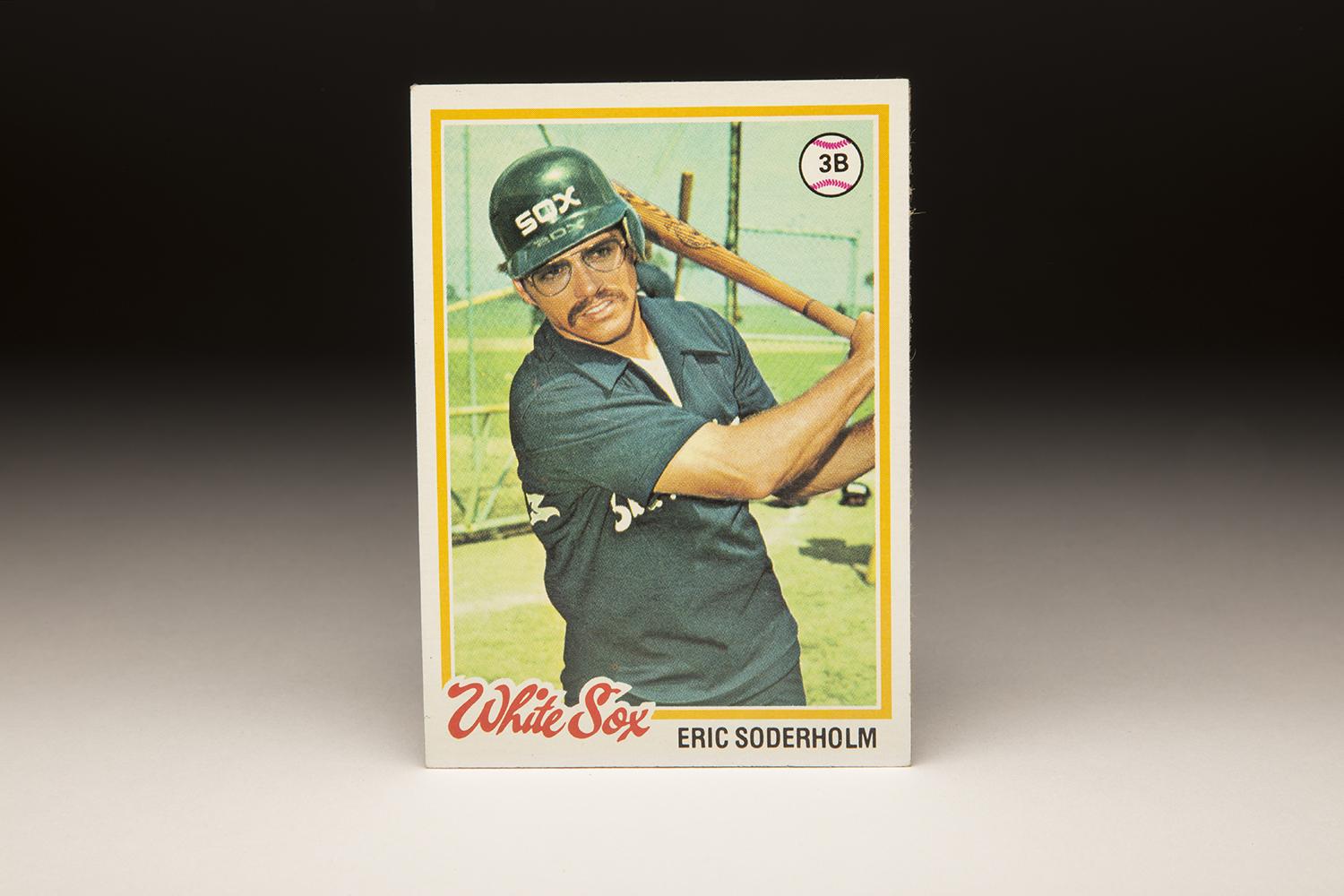

Soderholm’s 1978 Topps card helps us to relive part of the 1970s. The card shows him during Spring Training with his second team, the Chicago White Sox, as he follows through on a practice swing. The photo gives us a good view of the distinctive Soderholm look – those large wire-framed glasses, and that arched mustache, which was once fashionable in the major leagues. Also on full display is the White Sox’ memorable uniform of the late 1970s: The all-blue jersey and pants set, complete with a large collar that represented a throwback to the style of uniform used in the late 1800s.

Yes, dark colors and big collars were popular back then, as White Sox owner Bill Veeck showed us with his decision to trend “backward” in the late 1970s.

In learning about Soderholm, we can head all the way back to the late 1960s. In 1967, the Kansas City A’s drafted Soderholm as a shortstop out South Georgia College, but were unable to convince the Cortland, N.Y., native to sign. So the following year, he went right back into the draft pool, this time in the January phase of the draft. The Minnesota Twins made him their first-round draft choice and played him at short over the first two seasons of his professional career. In 1970, the Twins wisely moved him to third base, a better fit for him given his relatively pedestrian range.

Soderholm showed good power in the minor leagues in 1970 and 1971, enough to receive a promotion to the Twins late in the summer of ’71. Looking for an upgrade at third base, the Twins gave Soderholm regular playing time in September. He showed a good eye at the plate, but didn’t hit for either average or power.

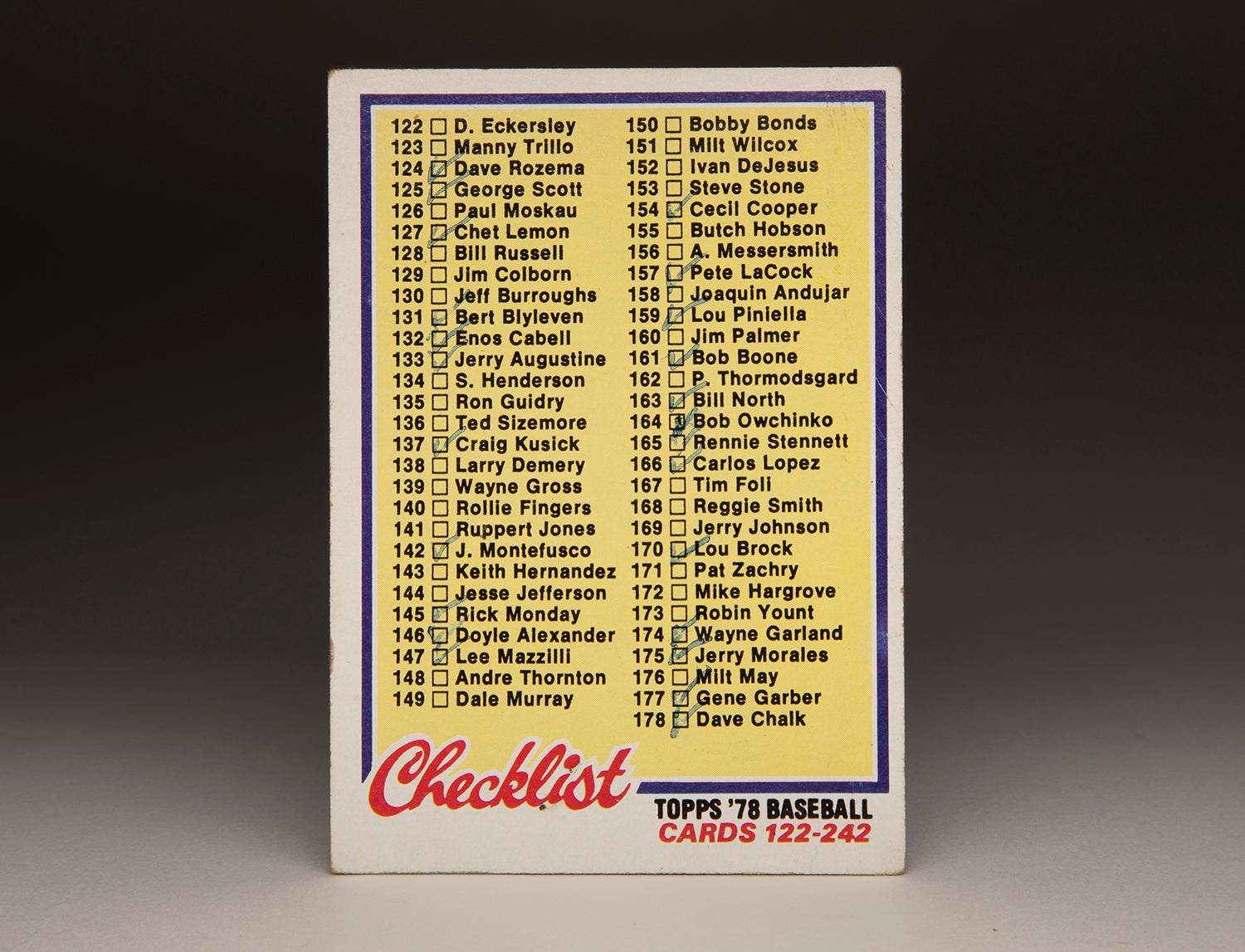

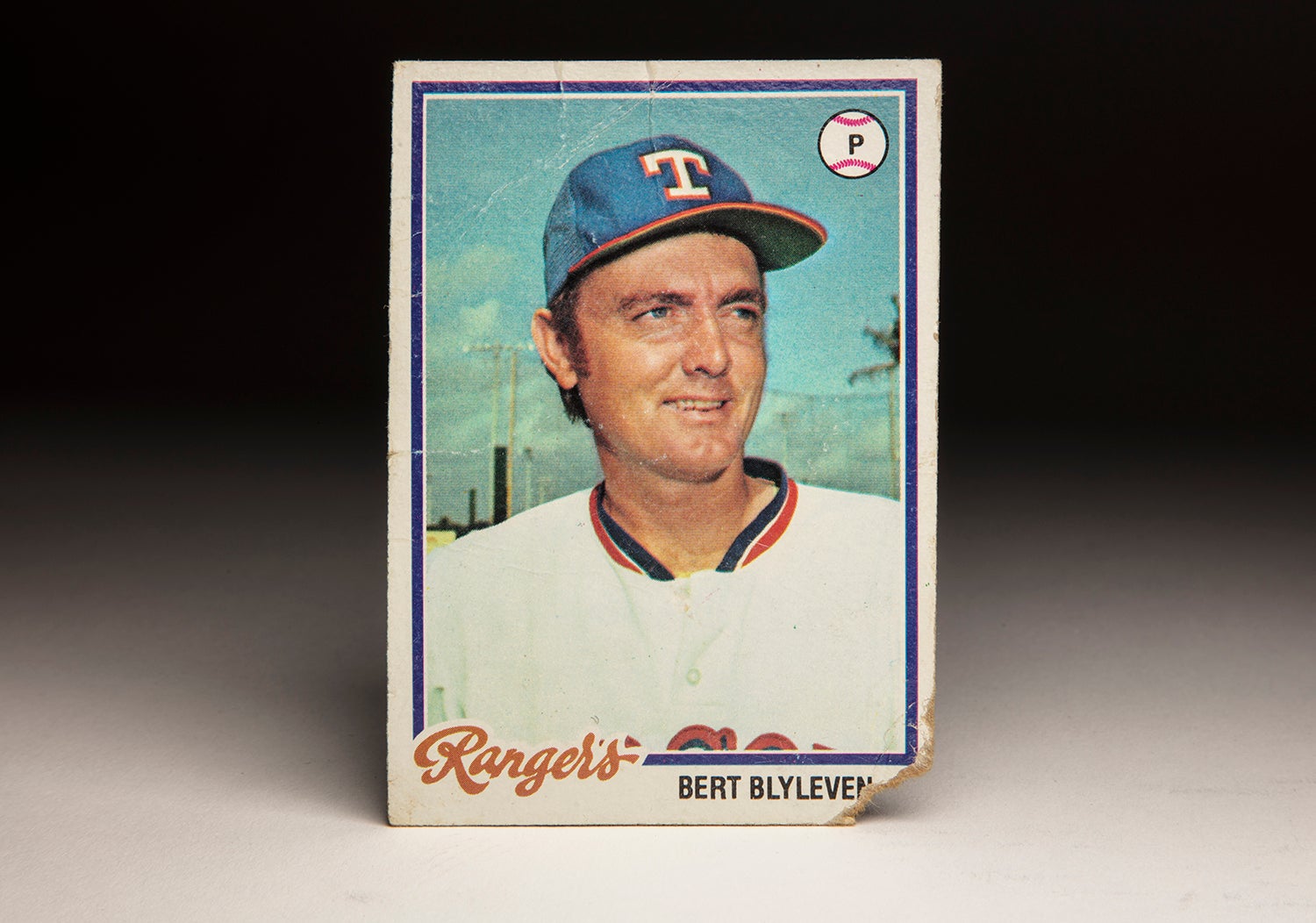

Soderholm’s September didn’t dissuade the Twins from giving him a further look in 1972. He played frequently, especially against left-handed pitching, but his batting average languished below .200. On the positive side, Soderholm hit 13 home runs, the third-best output on the Twins behind Hall of Famer Harmon Killebrew and outfielder Bobby Darwin.

In 1973, Soderholm reported to Spring Training, only to be demoted to Triple-A Tacoma prior to the season. Soderholm nearly quit. “Once I decided to report to Tacoma,” he told Twins beat writer Bob Fowler, “it took about half a season to get my head screwed on right. I just about gave up; I didn’t want to fight my way back to the majors.” But he did. On Aug. 16, the Twins traded veteran pitcher Jim Kaat, opening up a spot on the roster for Soderholm. Revitalized by his return to the big leagues, he batted .297 in 35 games and drew more walks than strikeouts, an indication of his growth as a hitter.

The Twins felt that Soderholm was ready for fulltime work in 1974. They made him their everyday third baseman and watched him put up solid numbers in 141 games: a .276 batting average, a .349 on-base percentage, and 10 home runs.

Soderholm showed more improvement in 1975, raising his batting average, his power production and his overall OPS (which was now approaching .800). On the verge of becoming one of the American League’s top third baseman, Soderholm suddenly hit an obstacle. On Aug. 20, he was walking on some property he had purchased in Minnesota when he fell into a storm sewer. He broke two of his ribs, resulting in the unexpected end of his season.

With his season over, Soderholm decided to also take care of his left knee, which had been bothering him for some time. He underwent surgery, but it was not a simple procedure. Doctors removed all of the cartilage in the knee and shaved away some of his knee cap. They also discovered the presence of arthritis in his knee and upper leg. After the operation was complete, doctors told Soderholm that he had less than a 50 percent chance of resuming his career.

Soderholm became determined to beat the odds. He began an eight-month rehabilitation, which included extensive work with Nautilus weight training machines. “Sometimes I’d work myself into a state of shock,” he told reporters in 1978. “I’d find myself on the floor, eyes glazed, vomiting. Then I’d get up and work some more.” Soderholm also immersed himself in aerobic training, something that was almost unheard of for baseball players of that era.

As Soderholm went through rehabilitation, he missed all of the 1976 season. By coincidence, Soderholm became a free agent at the end of ‘76, under the new system that had resulted from the Peter Seitz ruling and subsequent negotiations between players and owners. Given his inability to play in 1976, Soderholm did not exactly have much leverage in talks for a new contract. After the Twins offered him only a non-guaranteed contract, he did find a taker. He agreed to a guaranteed contract, but one that could be categorized as bargain basement. For the sum of $60,000, Soderholm agreed to play for the White Sox, who needed a third baseman badly.

When Soderholm reported to Spring Training in February of 1977, he felt confident in the condition of his knee. His doctor claimed Soderholm to be the strongest man in the major leagues – a testament to the success of his rehabilitation. One Chicago writer referred to Soderholm as the “Bionic Third Baseman,” a clear reference to Lee Majors’ popular TV show, The Six Million Dollar Man, which ran from 1974 to 1978.

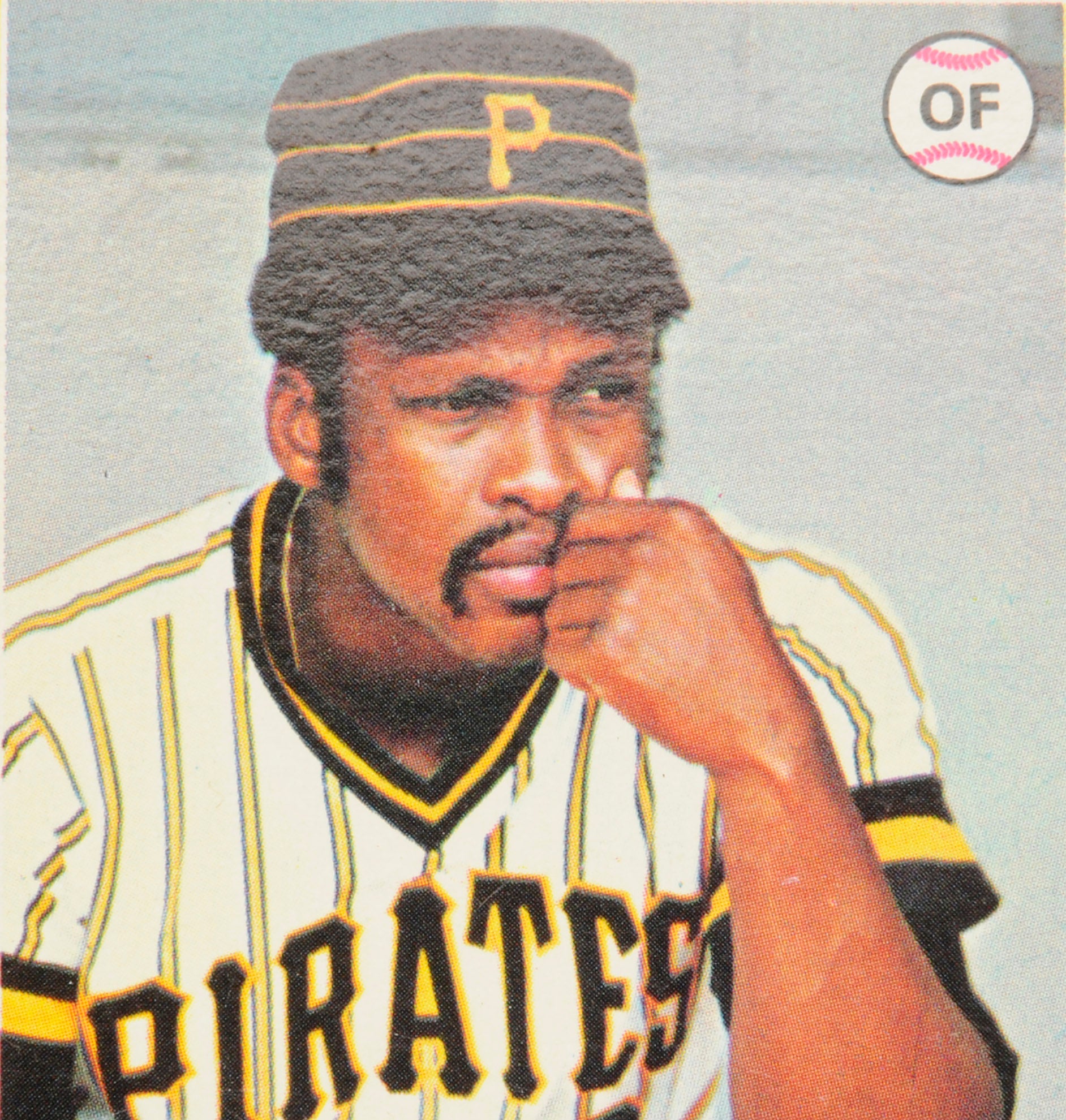

The Bionic Third Baseman became a revelation for the White Sox. Coming back from the devastation to his knee, Soderholm put up his best season ever. He batted .280 with 25 home runs, more than doubling his power output from his days in Minnesota. He also played a capable third base, committing only eight errors over a full season. In winning the Comeback Player of the Year Award, Soderholm became a key part of a White Sox team known as the “South Side Hit Men.” Led by Soderholm and the slugging duo of Oscar Gamble and Richie Zisk, the White Sox won 88 games to finish a surprising third in the American League West.

In 1978, Soderholm’s batting average and power slipped a little bit, but he remained productive and showed more durability, appearing in a career-high 143 games. On a White Sox team devastated by free agency, Soderholm remained one of the few holdovers from 1977 who carried success over into the summer of ’78. Off the field, he maintained diverse interests, including the hosting of a weekend radio show, something that he had started doing in 1977. He also told reporters about his hopes of opening up his own training center in Chicago, where he planned to use hypnotism and explore the mental side of conditioning.

A mediocre start to the 1979 season, coupled with the White Sox being in full rebuilding mode, put a temporary halt to those plans. At the June 15 trading deadline, the pitching-needy Sox traded Soderholm to the Texas Rangers for veteran right-hander Ed Farmer and a minor league prospect.

With a top-flight third baseman already in tow in Buddy Bell, the Rangers had a different role in mind for Soderholm. They used him as a kind of superutility player, backing up Bell at third, platooning with Pat Putnam at first, and filling in at DH. Playing in an irregular role, Soderholm hit .272, but with little power.

The Rangers liked Soderholm, but their glut of corner infielders and DH’s prevented him from taking on a more meaningful role with the team. According to baseball’s contractual rules, Soderholm also had the right to demand a trade. At the Winter Meetings, the Rangers found a deal, sending Soderholm to the Yankees for a pair of players to be named later.

Soderholm had mixed reactions to the trade, knowing that Graig Nettles was already occupying third base in New York. At first glance, some Yankee fans wondered the same. Why did the Yankees need Soderholm when they already had Nettles? Well, the Yankees felt they had become too left-handed, making them vulnerable to lefty pitching. They believed that Soderholm could occasionally spell Nettles against some of the tougher left-handers in the league, while also doing some work as a DH.

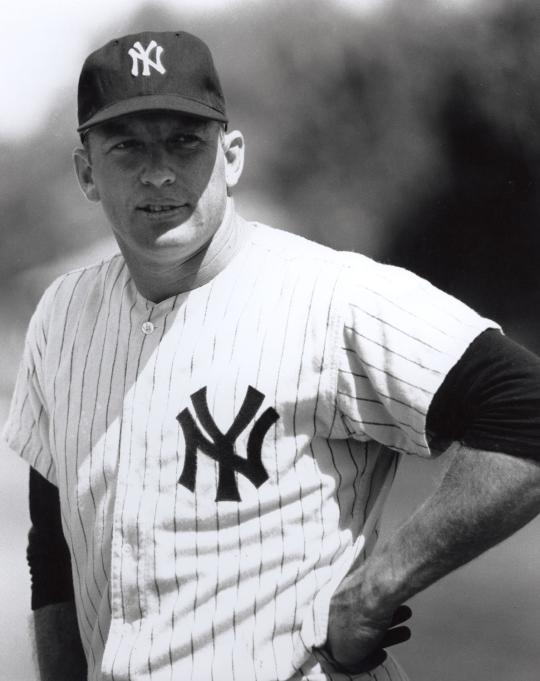

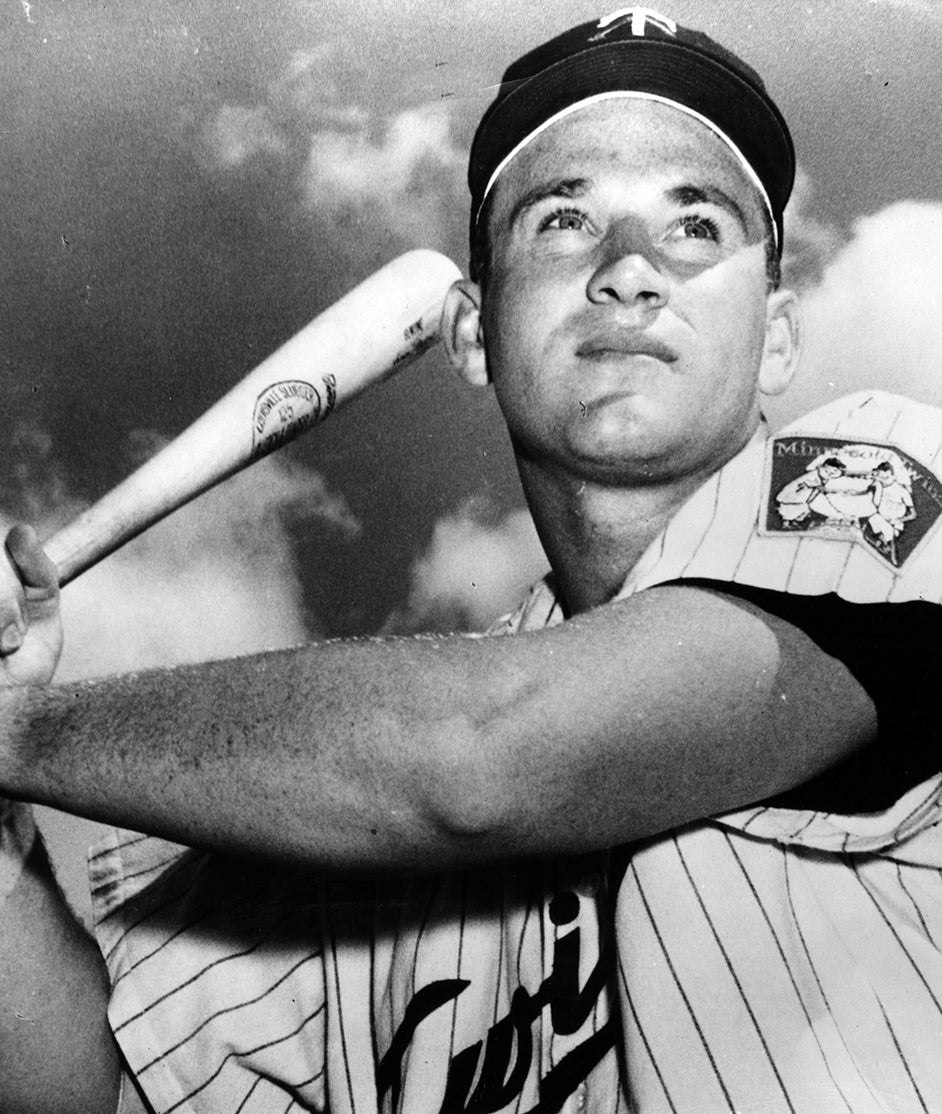

Spring Training with the Yankees provided some special satisfaction for Soderholm. A lifelong fan of the game, he had grown up idolizing Mickey Mantle. With Mantle in Yankee camp as a special instructor, Soderholm took advantage of the opportunity to secure his autograph. He also acquired signatures from Yogi Berra, Elston Howard, and Whitey Ford, all of whom were in camp as special instructors.

Yankee manager Dick Howser skillfully massaged Soderholm into the lineup, making sure that he played somewhere against lefties. Soderholm did well for the Yankees. Appearing in 95 games as a third baseman and DH, he hit .287, reached base 35 percent of the time, and compiled an OPS of .815. He became an important contributor to a deep and veteran-laden team that won 103 games and ran away with the American League East.

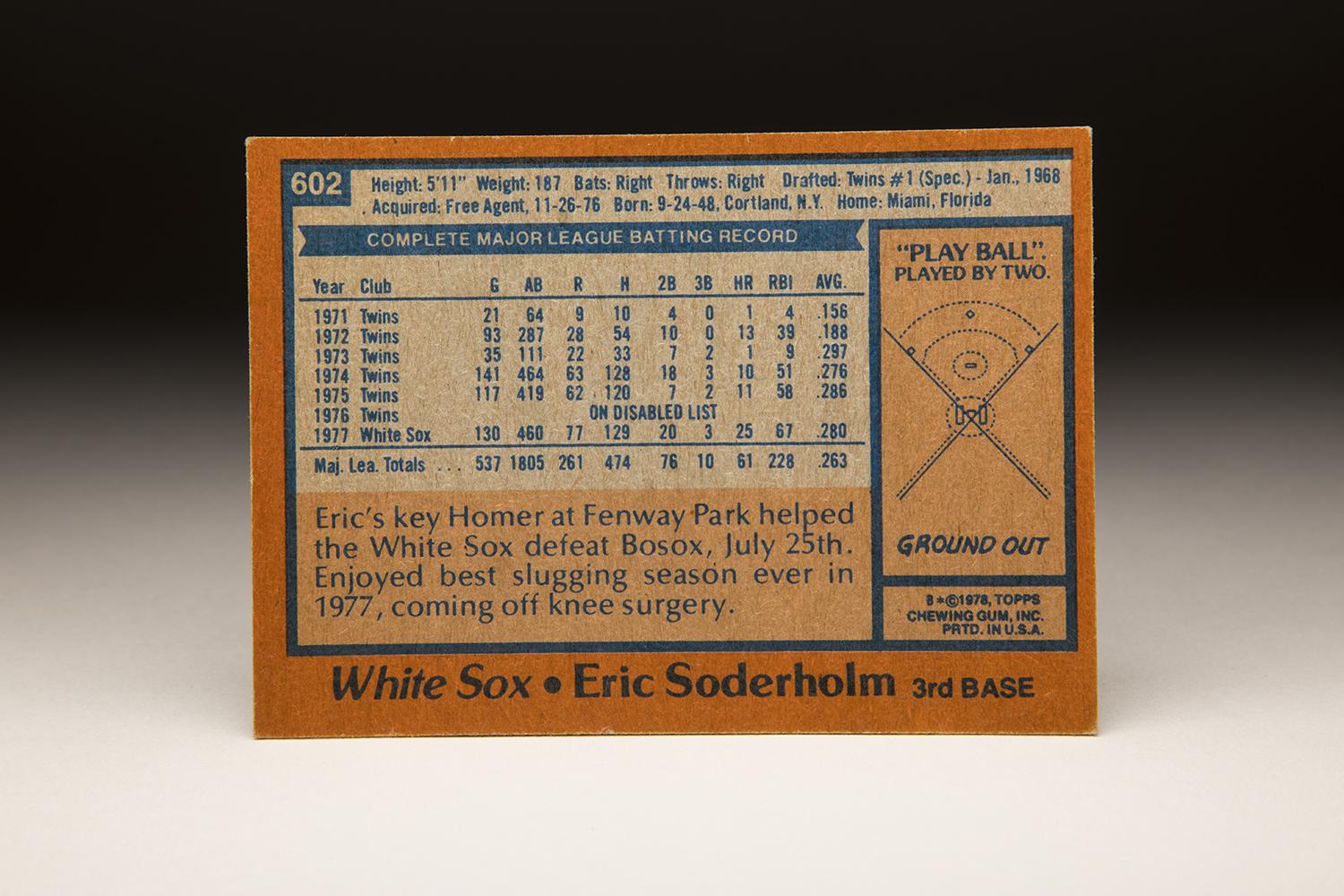

In 1972, Eric Soderholm hit 13 home runs, the third-best output on the Minnesota Twins behind Hall of Famer Harmon Killebrew (pictured above) and outfielder Bobby Darwin. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

A lifelong fan of the game, Eric Solderholm had grown up idolizing Mickey Mantle (pictured above). With Mantle in Yankees camp as a special instructor in 1980, Soderholm took advantage of the opportunity to secure his autograph. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

The only downside to Soderholm’s season was the finish. Soderholm slumped in August and September, prompting George Steinbrenner to refer to his hitting as “ridiculously bad.” A sensitive type, Soderholm admitted that the harsh words from the Boss hurt him.

In the ALCS, Soderholm came to bat only six times, as the Yankees lost three straight game to the Kansas City Royals. No one knew it at the time, but Soderholm had played his final game as a major leaguer. Even though he was only 31, he would never again appear in a big league boxscore.

Just before Soderholm reported to Spring Training in February of 1981, he slipped on some ice near his home in Chicago. Soderholm felt pain, but he expressed hope that he could at least DH for the Yankees. Ever the gamer, he reported to Ft. Lauderdale, determined to play through the pain. But his knee hurt too much. Soderholm was in such pain that he had to undergo his fifth knee operation. This time, the operation repaired the anterior cruciate ligament in his right knee. The Yankees placed him on the disabled list prior to Opening Day. He would remain there for the entire year.

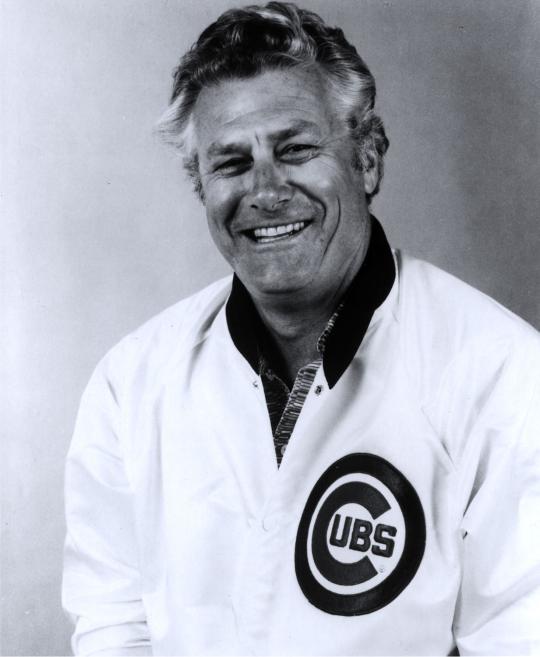

After sitting out all of 1981, Soderholm received an invitation from the Yankees to attend Spring Training in 1982, but instead accepted an invite from Dallas Green, who was running the Chicago Cubs. Wanting to win Comeback Player of the Year honors for the second time in his career, Soderholm reported to camp and stayed with the Cubs for about three weeks, but he simply could not move or run like a typical major leaguer. “When you get to the point where it’s embarrassing and you can’t move around, it’s time to go,” Soderholm told Chicago writer Dave van Dyck. “When I try to turn up the speed, it feels like my knees are falling apart.” Soderholm realized that it was time to leave the playing field.

Soderholm became an advance scout for the Cubs, serving in that capacity for two years, but the low pay convinced him to look elsewhere. By accident, he fell into the sports ticketing business, before opening up his own wellness center, known as SoderWorld. The business has become hugely successful, with its state-of-the-art facility and a wide variety of services, including massage therapy, yoga, and holistic healthcare.

When it came to his own health, Soderholm didn’t have much luck. One wonders how he would have fared today, given the advances in surgery and general medicine. But he should have no regrets. He extracted everything he had from those fragile knees. A lesser man might have seen his career come to an end in 1975. Through hard work and a level of determination that could best be described as steely, the Bionic Third Baseman would have made Lee Majors proud.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame