- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1978 Topps Tito Fuentes

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Tito Fuentes

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

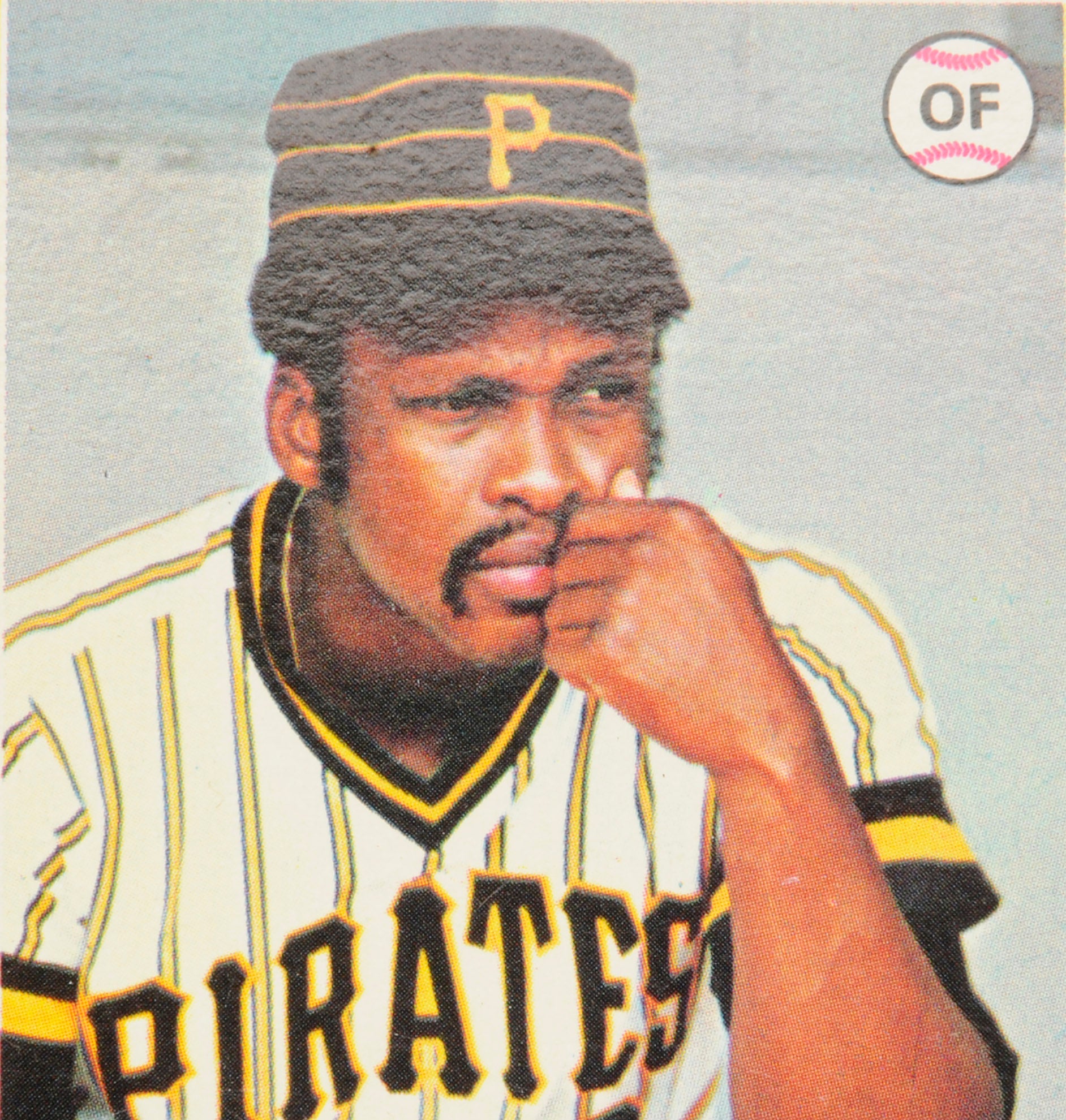

Even if his name wasn’t included on the face of a baseball card, it would have been fairly easy to identify Tito Fuentes on his 1970s Topps offerings.

Fuentes was the guy who was usually wearing a headband; he was the Slick Watts of Major League Baseball. In fact, I can’t recall too many other ballplayers, if any, who sported visible headbands during the 1970s. Fuentes’ famed headband first made an appearance on his 1974 Topps card, in the form of a bright gold band worn around his San Francisco Giants cap.

Fuentes showed off the headband again on his 1976 Topps card. By then, Fuentes was playing for the San Diego Padres. This time, he wrote his name, “Tito,” in magic marker on the headband. There could be no mistaking that it was Rigoberto “Tito” Fuentes.

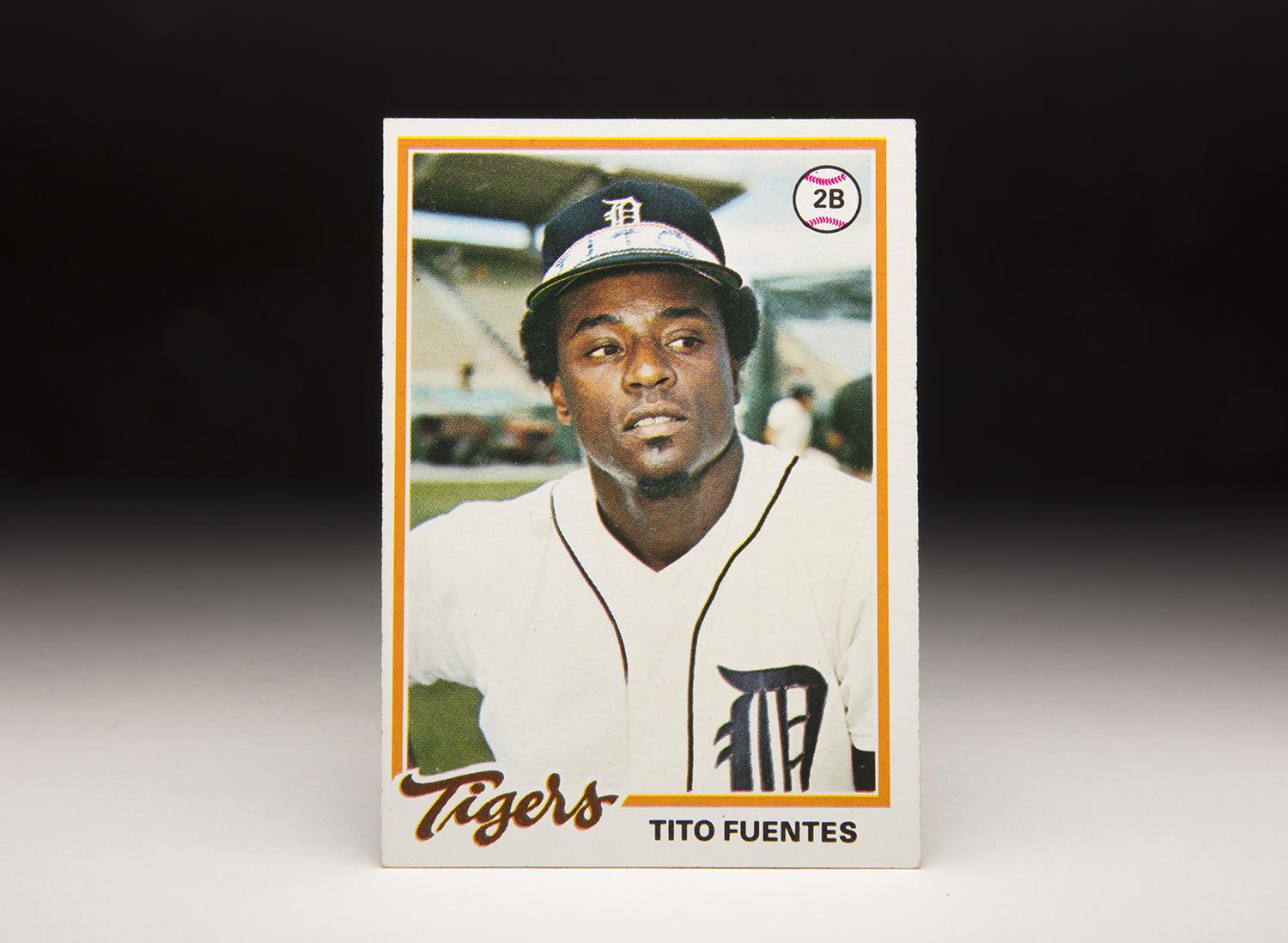

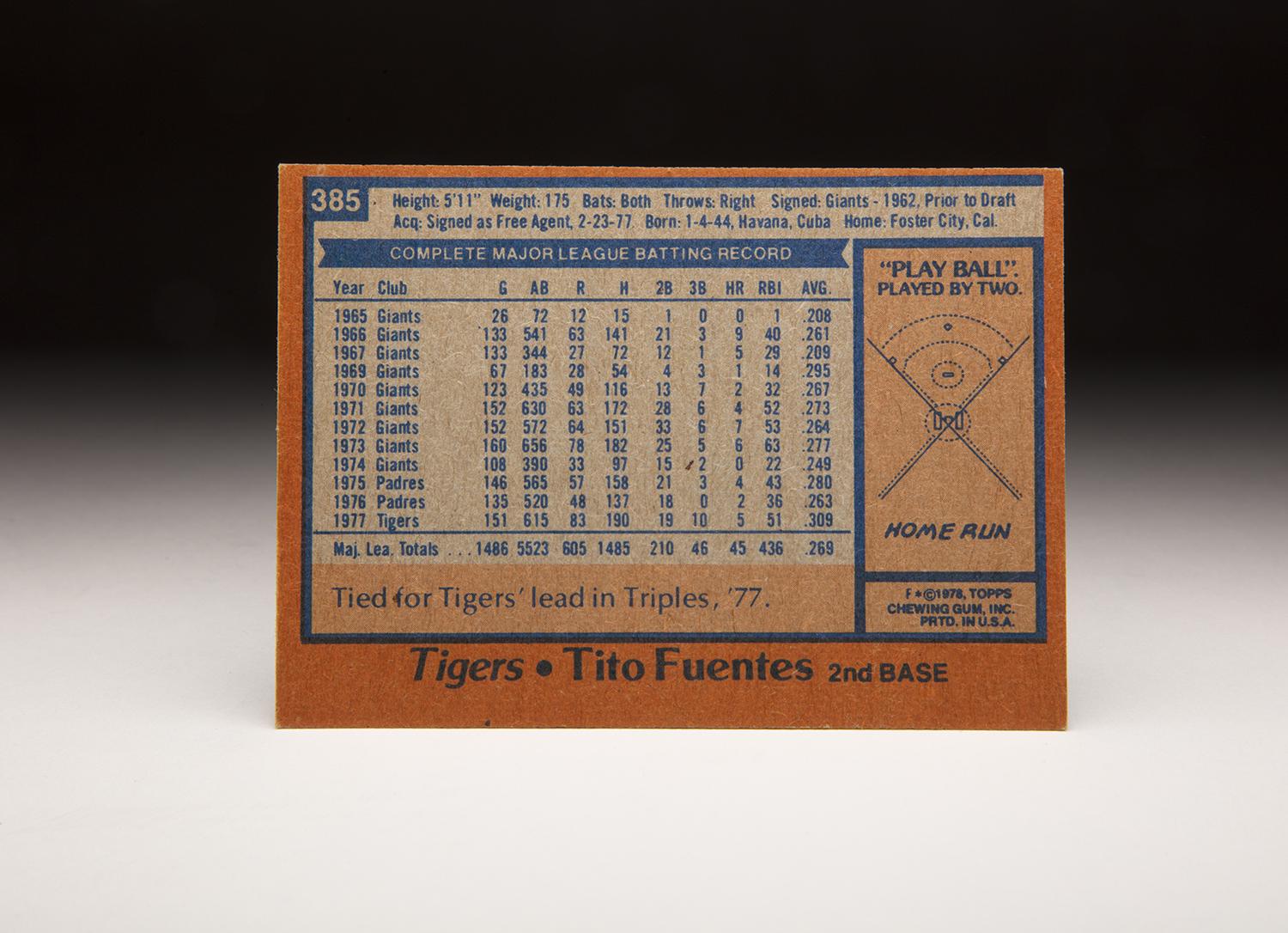

Then came Fuentes’ 1977 Topps card, a pseudo in-action card. For this selection, Fuentes changed the positioning on his headband, this time wearing it directly on his head, while tucked under the bottom of the cap. And then there was his final card for Topps, which came out in 1978. By this time, Fuentes was playing for the Detroit Tigers and had switched the band color from gold to white, with “Tito” once again printed on the front of the band.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Fuentes’ 1978 card is notable for a couple of reasons. The unusual nature of the headband contrasts with the dignified, conservative nature of the Tigers’ home uniform, long one of the stateliest set of double knits worn by any major league team. Fuentes also had his own sense of facial sense of fashion; notice the small chin beard that he sported on the 1978 card. Chin beards have become common in today’s game, but in the late 1970s, they were hard to find. Most players wore either full beards or mustaches, or went with the clean shaven look. A small beard protruding from the chin was something relatively unique. It was just another example of how Fuentes, a one-of-a-kind character if there ever was one, liked to do things his way, regardless of the trends of the day.

That is not to say that Fuentes wore a chin beard or a headband from the very beginning of his career. He came up in the mid-1960s, at a time when the sport remained highly conservative and would remain so even in the face of the developing American counterculture. Some of Fuentes’ flashiness would have to wait, at least for a little while.

Prior to the 1962 season, the Giants signed Fuentes out of Havana, Cuba. He was the last Cuban to join Organized Baseball before strained relations between Fidel Castro and the United States effectively stopped the pipeline of players leaving Cuba to pursue careers on the American mainland. Fuentes spent his first professional season split between two teams at the Class D level, before moving up to Class A ball in 1963. Fuentes impressed the Giants with his speed, strong throwing arm, terrific hands, and an unusual defensive versatility that allowed him to play just about anywhere on the infield.

After hitting .338 for Decatur in the Midwest League, the Giants bumped Fuentes up to Double-A El Paso. The following season, he split the year between Double-A and Triple-A, playing for El Paso and Tacoma, respectively. In 1965, Fuentes surprised everyone by hitting 20 home runs for Tacoma; of course, that kind of home run production was mostly due to the hitting conditions of the Pacific Coast League, rather than a true indication of newfound power.

Given his gaudy numbers at Tacoma, the Giants promoted him to the big league roster in August of ’65. Only a few days after his recall, on Aug. 22, the Giants became embroiled in the famed incident involving Juan Marichal and the Dodgers’ John Roseboro. Fuentes, who was kneeling in the on-deck circle when the equivalent of a Pier Six brawl broke out between the two rivals, responded by running out onto the field with his bat in hand. Brandishing the bat like a baton, Fuentes refrained from using it as a weapon; thankfully, teammate Willie Mays stepped in and pulled Fuentes out of the center of the skirmish before he might have swung the bat at one of the Dodgers.

The Giants used Fuentes as a utility infielder in August and September, playing him behind Hal Lanier at second, Dick Schofield at shortstop and Jim Ray Hart at third. In 72 at-bats, the right-handed hitting Fuentes struggled, batting .208. Then again, he was still only 21, a raw and relatively inexperienced talent.

The 1966 season would represent a breakthrough for Fuentes, who replaced Schofield at shortstop, hit .261 with nine home runs, and finished third in the NL Rookie of the Year balloting. All in all, it was a good rookie season for Fuentes, though it did produce one alarming statistic. Fuentes drew only nine walks, a testament to his overzealous approach at the plate.

Fuentes also took some criticism that summer. Some opponents called him a “hot dog,” a label that Fuentes hated. During a game against Houston, Astros pitcher Turk Farrell shouted at Fuentes from the mound, calling him a hot dog. Fuentes sneered in return, but did not charge the mound. At the end of the inning, the hulking Farrell crossed paths with Fuentes and apologized. “I’m sorry, Tito,” Farrell said according to the Sporting News. “I shouldn’t have said that.” Fuentes accepted the apology.

In 1967, Fuentes endured the dreaded “sophomore jinx.” Though he drew a few more walks, the bottom fell out of his hitting in almost every other way. He hit only .209 and saw his on-base percentage fall below .300. The situation reached such a level of desperation that the Giants approached him about the possibility of switch-hitting.

Fuentes agreed to the experiment. In 1968, the Giants sent him back to Triple-A so that he could work on switch-hitting, but injury problems kept him sidelined for most of the summer. In 1969, the Giants returned him to Triple-A, where he batted .340 and compiled an on-base percentage of nearly .400. Wholly impressed, the Giants recalled him in midseason, this time using him as a combination shortstop and third baseman. The Giants hoped that Fuentes would improve the left side of the infield, which featured virtually no pop from either Lanier or Jim Davenport.

In 67 games, Fuentes batted .295 with an on-base percentage of .350. The Giants hoped that he could take on a larger role in 1970. He did appear in 123 games, but without a regular position, instead filling in at second, shortstop, and third. Offensively, he showed considerable improvement in terms of plate discipline. He walked 36 times, by far a career high for the free-swinging Fuentes. He also adapted well to the new artificial surface that the Giants installed at Candlestick Park.

By now, Fuentes had fully established a reputation as one of the most colorful players in the National League. Prior to each at-bat, he tapped the handle of his bat against home plate, flipped the bat into midair, and then grabbed it before assuming his place in the batter’s box. He also loved to talk to opponents during games, to the point that he became known as “Parakeet.” (Old school opponents hated Fuentes’ propensity to talk, but players of a younger generation embraced his flair for conversation.)

And then there was his fashion sense. Not only did Fuentes sport headbands during games, but he wore multiple gold chains around his neck, something that was rarely done by athletes in that era. He also sported a gold tooth. Off the field, Fuentes was no less flamboyant. He dressed in expensive suits, some of which were bright red in color. His suits usually featured large lapels, the type that were all the rage in the 1970s. He also had a habit of wearing many rings on his hands, sometimes as many as eight at a time.

In 1971, Fuentes enjoyed the kind of breakthrough season that he had been seeking since first joining the Giants. With Ron Hunt having been traded to Montreal, manager Charlie Fox decided to stop using Fuentes as a jack-of-all-trades and made him the team’s everyday second baseman. Fuentes responded by fielding his position well, where his fast hands made him especially good on the double play, and hitting a solid .272, with 12 stolen bases. His walk total fell in half, all to the way to a meager 18, but he contributed in other ways, driving in 53 runs and running the bases aggressively. He became an important part of a Giants team that won the National League West, earning a spot in the NLCS against the Pittsburgh Pirates.

On a personal level, Fuentes’ wife gave birth to a son in September. The baby arrived on Sept. 29, the day that the Giants clinched the division title. In honor of the occasion, Fuentes decided to give his new son the name of “Clinch.”

Fuentes would continue to play well in 1972, hitting .264, but his fielding became a concern. He had plenty of range, but also made a ton of errors, sometimes on balls hit right at him. But in 1973, Fuentes completely upped his game. He cut down his error total to six, the lowest figure for a National League second baseman since Jackie Robinson, a player that he had admired during his youth. Fuentes also batted .277, while earning some MVP consideration from the writers. Teaming with young shortstop Chris Speier, Fuentes helped the Giants finish a respectable third in the Western Division.

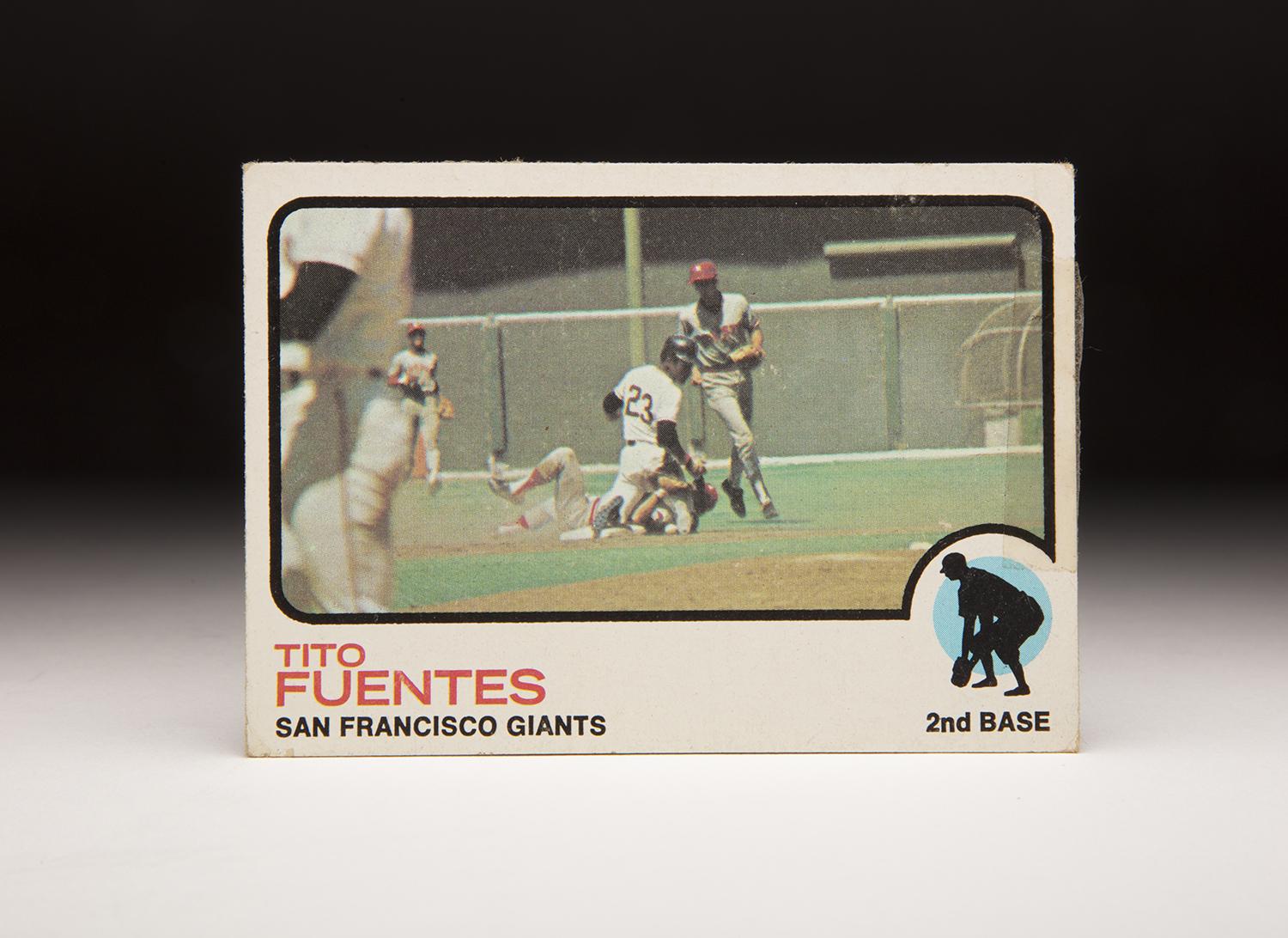

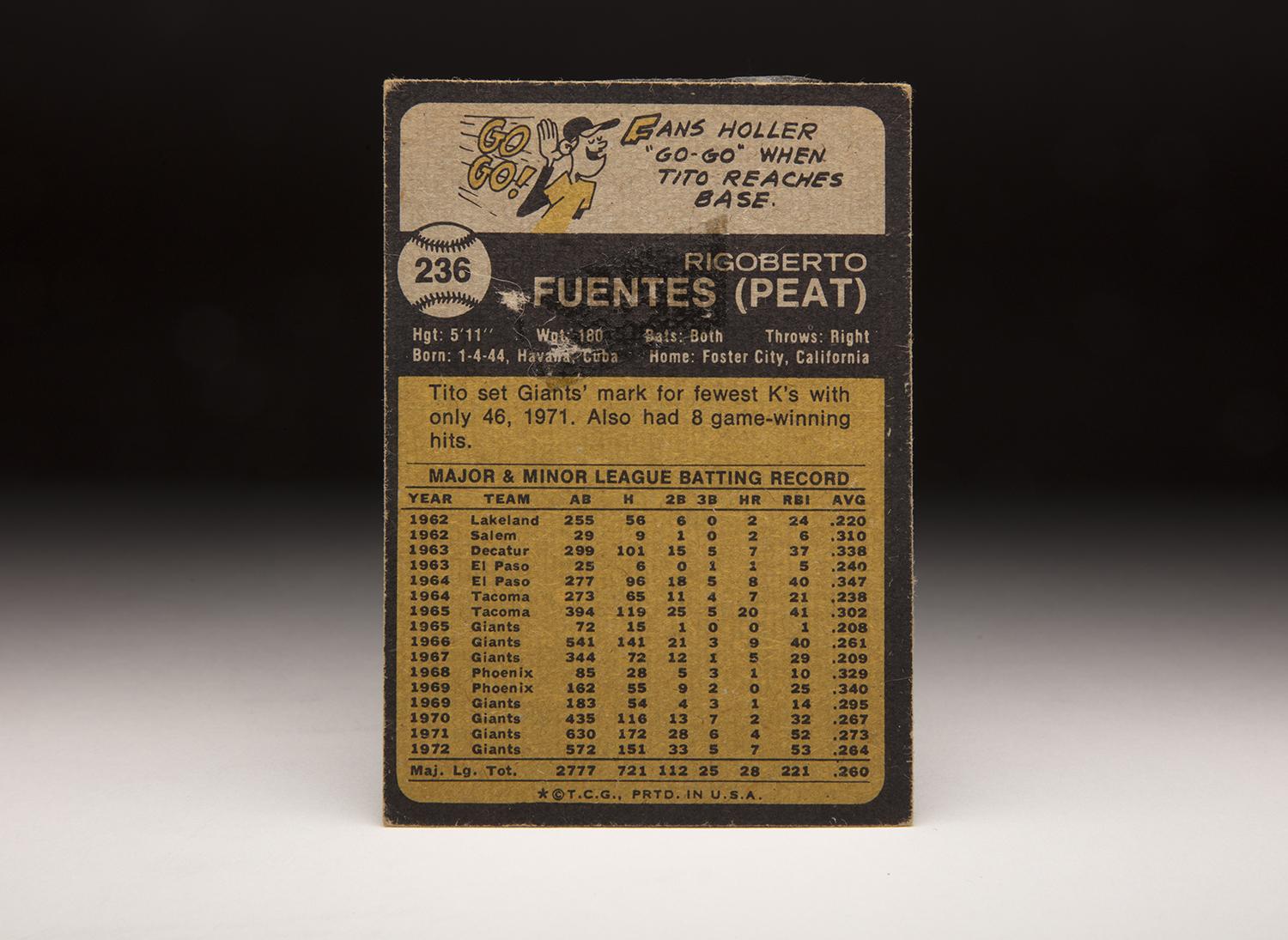

The 1973 season also brought some humor. Fuentes’ Topps card caught the attention of a few collectors because of the unusual “action” that it showcased during an afternoon game at Candlestick Park. On the card, Fuentes appears to be sitting on an unknown infielder (perhaps Tommy Helms) for the Houston Astros, the result of a strong takeout slide at second base.

With the Giants, Fuentes became a fan favorite. The Giants’ faithful regularly chanted “Ti-To” during his at-bats. When he reached first base, the fans at Candlestick yelled “Go! Go!,” hoping that he would steal second base. The fans also marveled at Fuentes’ athleticism. On takeout slides at second base, Fuentes leapt into the air and showed off his unusual hang time, a trait of his athletic ability.

Fuentes also became a favorite with the media. He sometimes responded to questions with unusual sayings. On one occasion, he expressed his displeasure with pitchers who threw at him, before making a rambling remark that would have made Casey Stengel blush. “They shouldn’t throw at me,” said Fuentes, according to an article by Michael Fitzgerald at Recordnet.com. “I’m the father of five or six kids.”

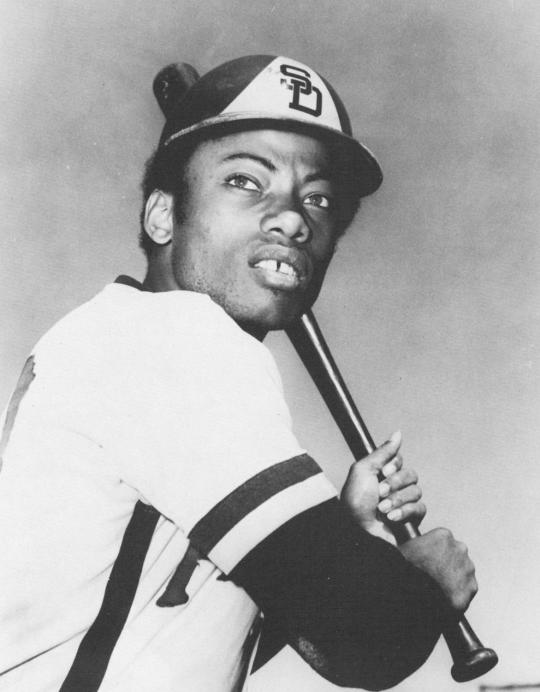

At 29, Fuentes appeared to be in his prime. But the 1974 season would bring heartache, mostly in the form of a back injury, which limited him to barely over a hundred games. Affected by the soreness in his back, he hit no home runs for the season, and saw his on-base percentage sink below .300. The condition of his back also prevented him from making plays on balls hit up the middle, which would force him stop and throw back against the momentum of his body. The Giants became so concerned about Fuentes’ back that they moved him that winter, sending Fuentes and pitching prospect Butch Metzger to the Padres for a younger switch-hitting infielder in Derrel Thomas.

The reaction to the trade was resoundingly negative in the Bay Area, where fans loved Fuentes and his stylish ways. Fuentes himself hated to leave the organization, but also viewed the situation philosophically. “Baseball’s a business,” Fuentes told Pat Frizzell, corresponding for the Sporting News. “I’m not the only one who has been traded. Willie Mays was, too, after 20 years with the Giants.”

In a significant development, Fuentes’ back problems eased in 1975. He batted .280, a career high. But his lack of patience resulted in a subpar on-base percentage. In 1976, when his batting average fell by 17 points, his inability to reach base became a greater concern. The Padres allowed Fuentes to venture into baseball’s newly created system of free agency. Fuentes considered an offer from the Japanese Leagues, but turned it down when the Tigers came calling with a one-year offer.

Of all the free agent signings that winter, the Fuentes contract, paying him all of $90,000, received virtually no attention. Dissatisfied with the lack of hitting from incumbent second baseman Pedro Garcia, the Tigers hoped that Fuentes would serve as a stopgap – until the arrival of heralded prospect Lou Whitaker. Fuentes turned out to be far more than a stopgap. Playing in 151 games, Fuentes batted .309 with 38 walks and an OPS of .745, all career highs. It was by far his best offensive season, even though he was 33 years old.

By 1978, the Tigers felt that Whitaker was ready. Still, given Fuentes’ level of production, it seemed sensible to keep the veteran around as a backup at second and third, and perhaps even as an occasional DH. Instead, the Tigers decided to part ways. In January, the Tigers sent Fuentes to the Montreal Expos. All the Tigers received in return was $20,000.

The acquisition of Fuentes thrilled the Expos. Their general manager, Charlie Fox, had served as one of Fuentes’ managers in San Francisco. Fox loved Fuentes’ attitude and enthusiasm for the game. “I’ve never seen a player go all out like Fuentes for every ball hit in his direction,” Fox told Ian MacDonald, correspondent for the Sporting News. “I’ve seen few players stay and fight every pitch better than Fuentes. That’s a player.”

Fox envisioned Fuentes as Montreal’s regular third baseman and simultaneous backup to Dave Cash at second base. That plan never came to pass. Unable to negotiate a new contract, Fuentes took the Expos to arbitration and lost the case. Left bitter by that result, he reported to Spring Training in a less-than-ideal mood. Fox, manager Dick Williams, and the Expos’ coaching staff noticed the change in Fuentes. Shortly before the Expos broke camp, Montreal released Fuentes. He would never play a game for the Expos.

The late spring release hurt Fuentes in terms of finding work elsewhere. Famed sportswriter Dick Young reported that Fuentes was “headed for Japan,” but that never came to pass. When no other major league team stepped forward, Fuentes moved on to the Mexican League, playing there for a couple of months. He then received a tryout with the New York Yankees, who already had Willie Randolph at second base. The Yankees gave Fuentes a look, but decided to pass, saying that they wanted a second baseman with more power. It was a strange argument, given that Fuentes had never hit with power during his major league career. Some wondered why the Yankees had given him a tryout in the first place.

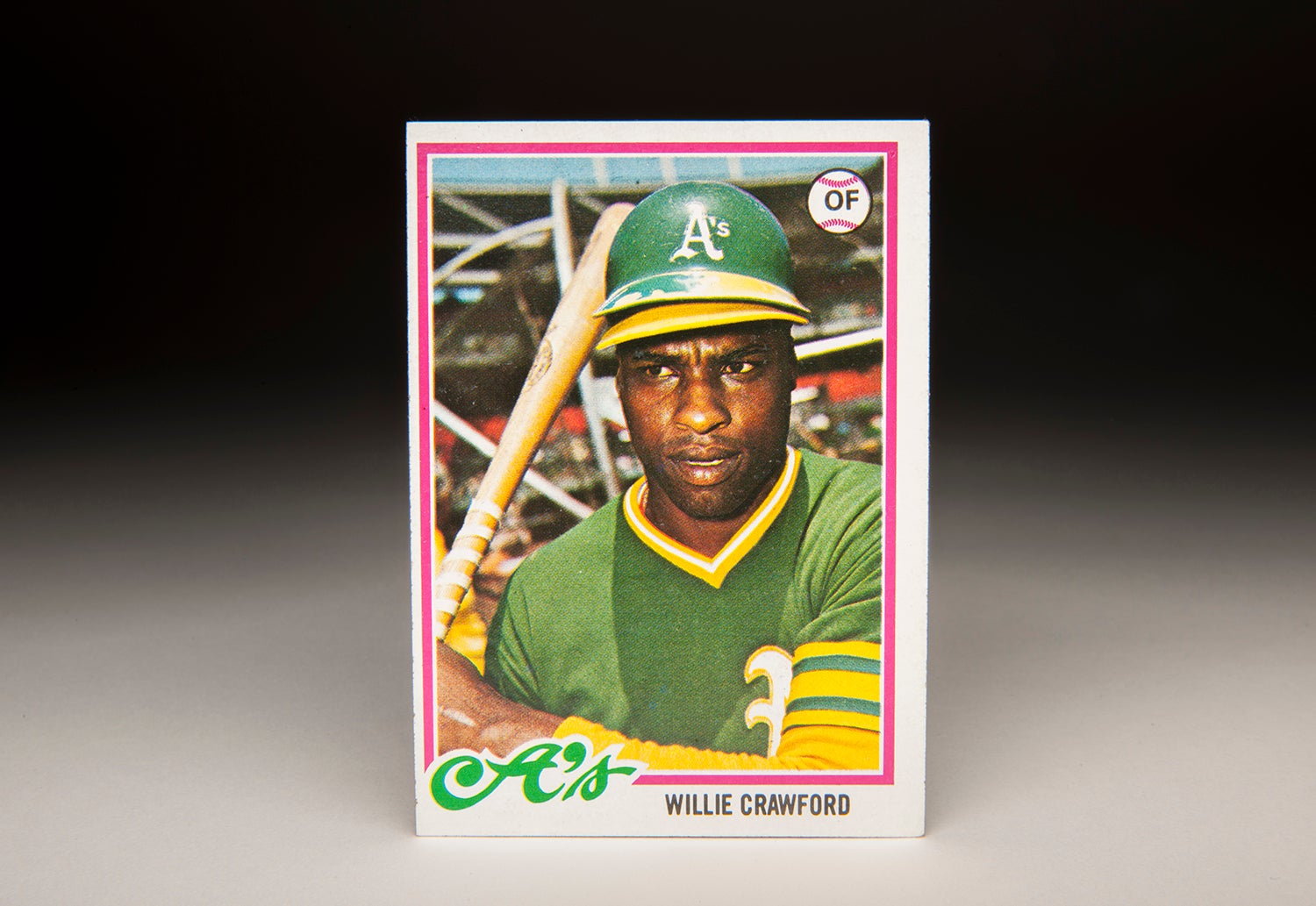

Still searching for a job, Fuentes found a home with a team where fading veterans often landed: Charlie Finley’s Oakland A’s. With Mike Edwards and Steve Staggs both lacking at second base, the A’s desperately needed a second baseman. They agreed to sign Fuentes, but after only 13 games in which he put up an OPS of .322, the A’s gave up on the veteran and released him.

The release by Finley ended Fuentes’ big league career, but he would find one more job in 1979.

The newly formed Inter-American League, an independent minor league, had a desire for brand name veterans.

Fuentes signed with Santo Domingo, batted .250 in 24 games, and then saw the league go up in smoke, bankrupted by failing franchises and unpaid debts. Fuentes’ playing days officially came to an end.

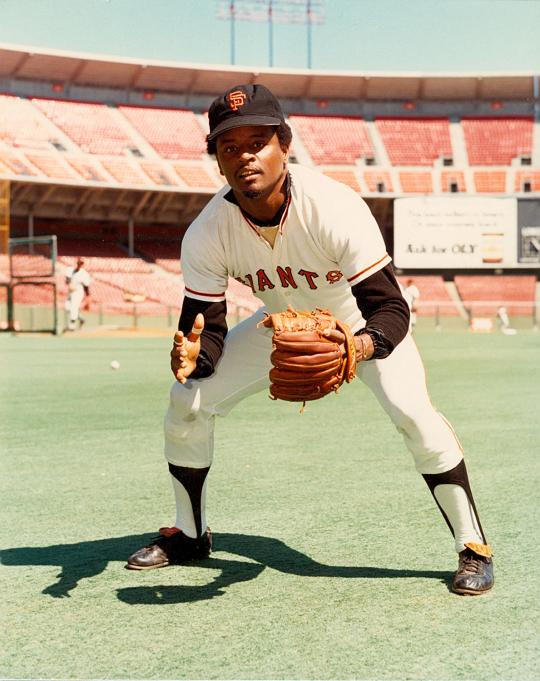

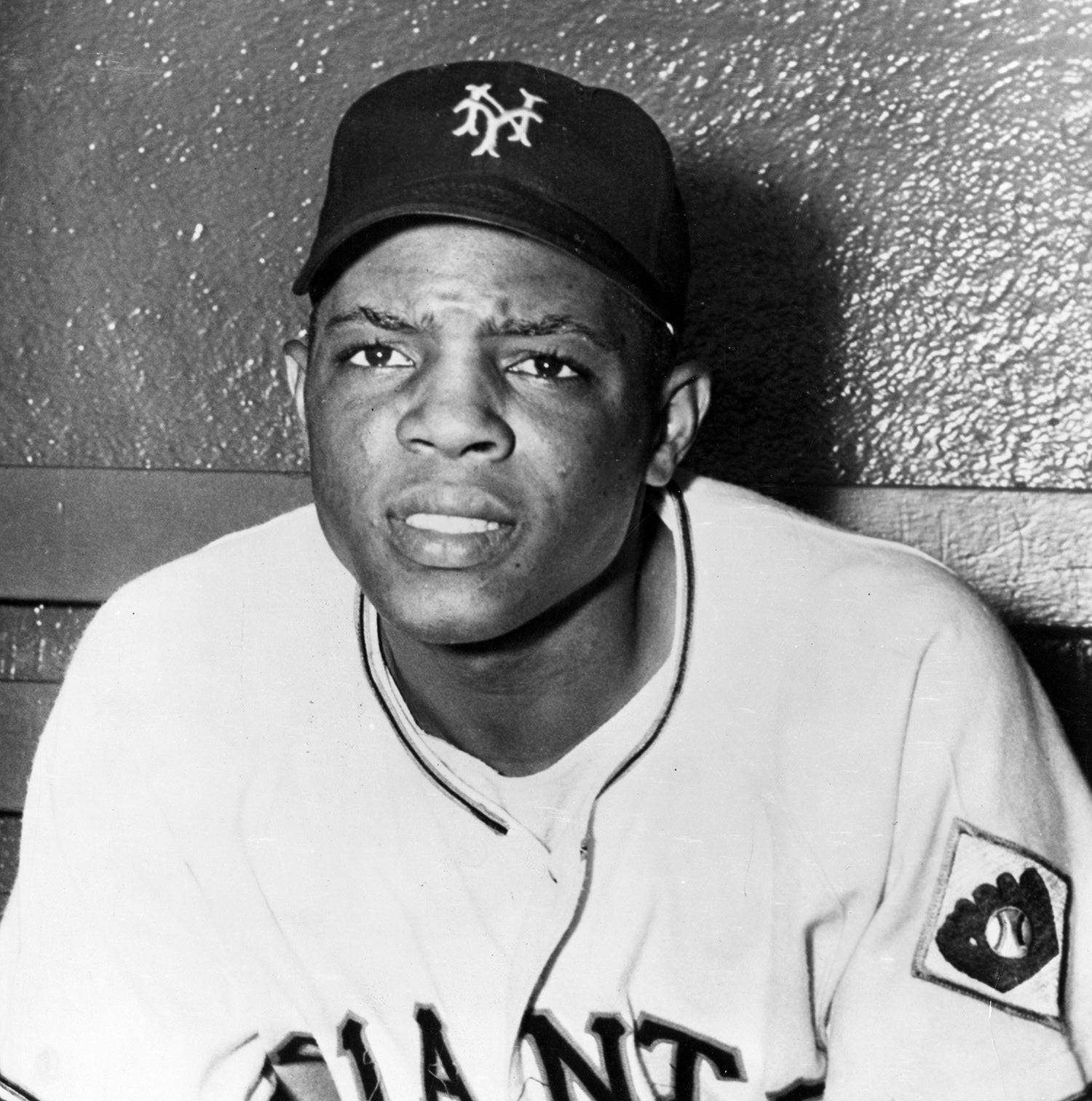

Tito Fuentes played for the San Francisco Giants from 1965-67 and again from 1969-74. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

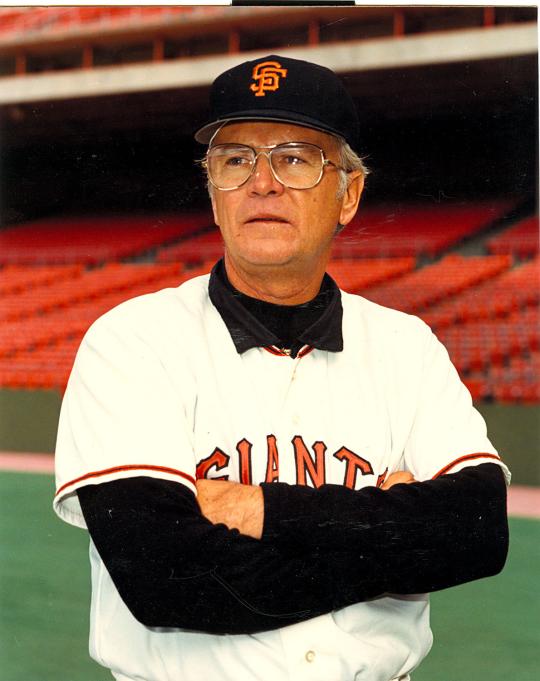

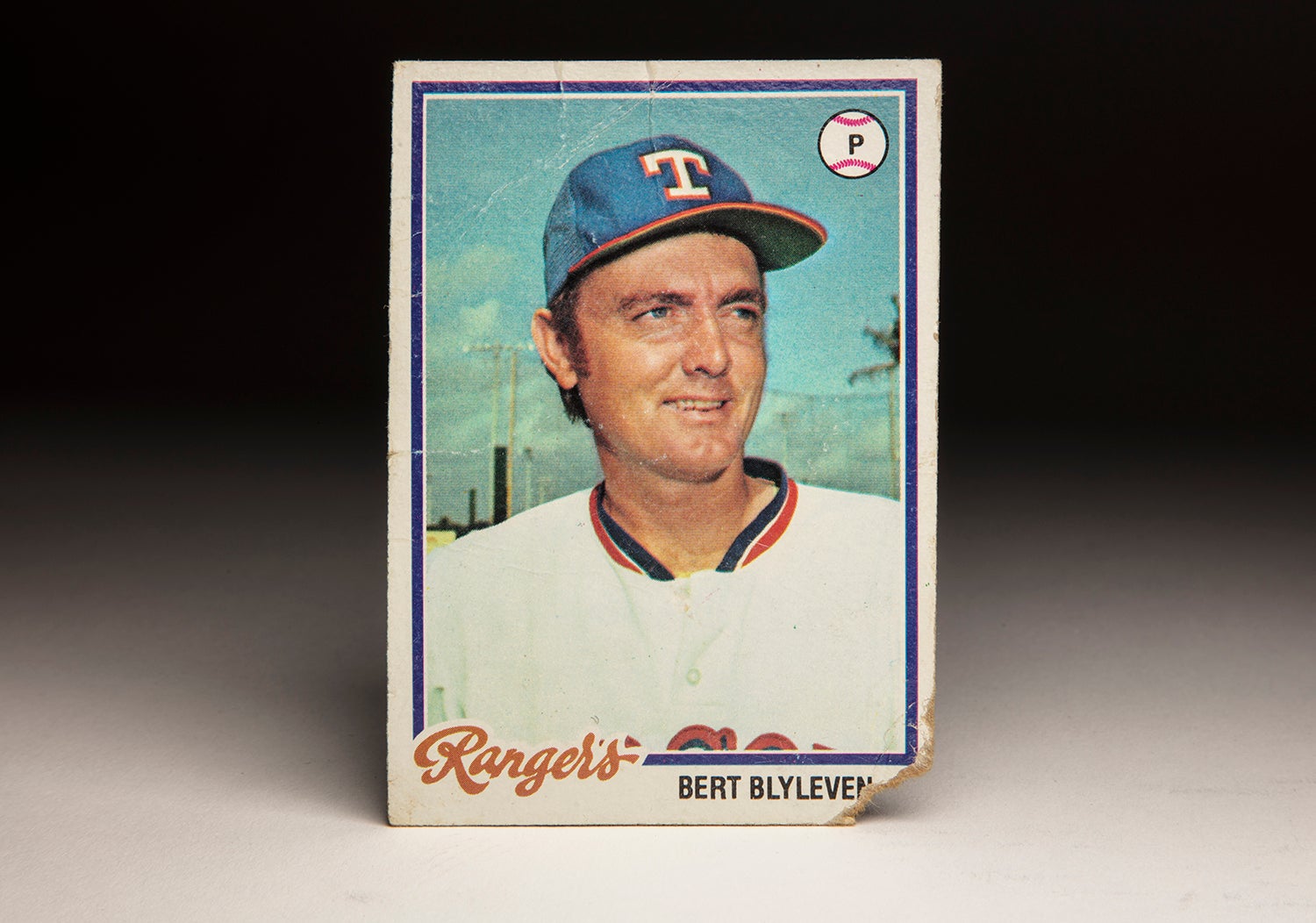

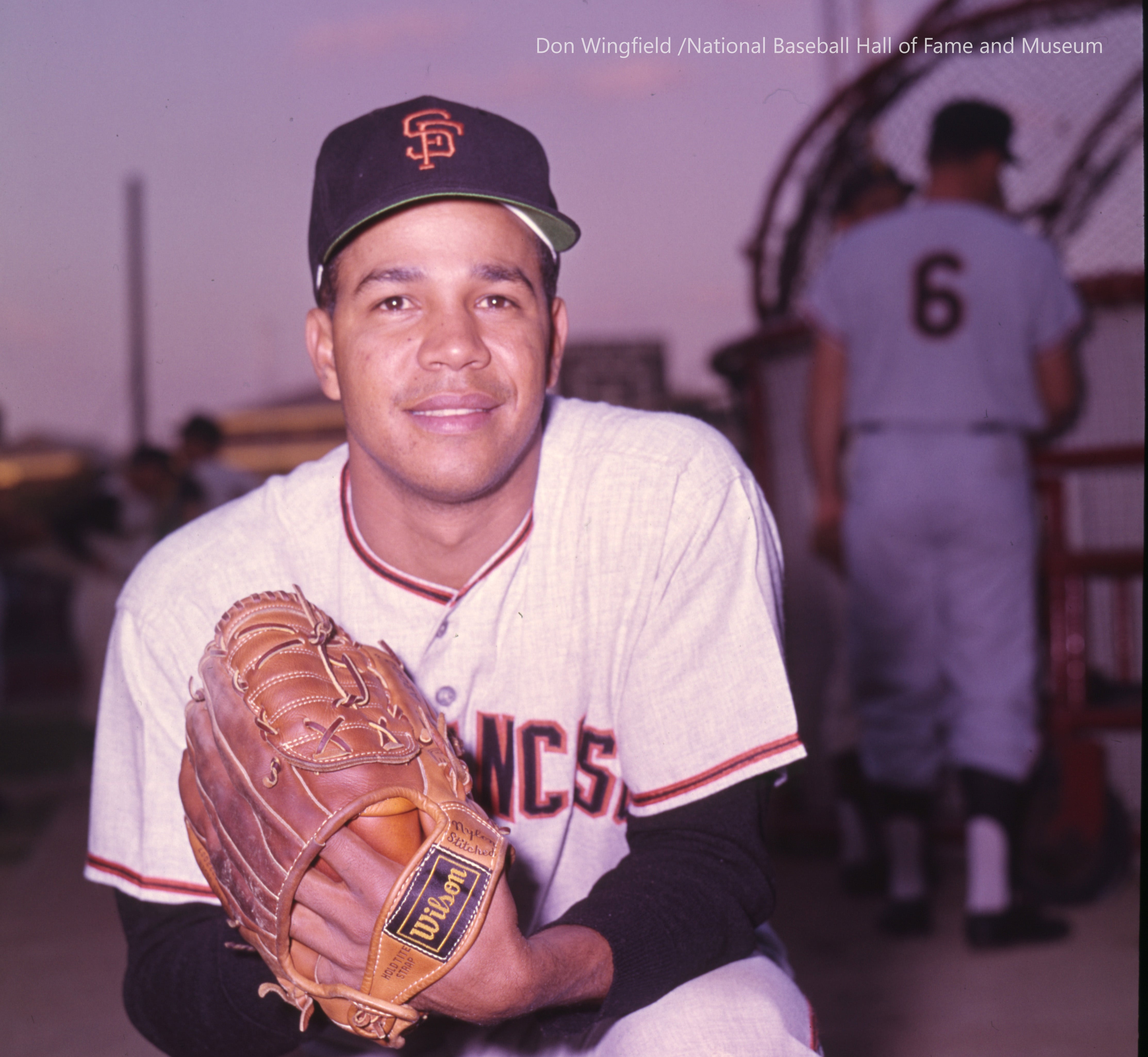

San Francisco Giants manager Charlie Fox loved Tito Fuentes’ attitude and enthusiasm for baseball. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

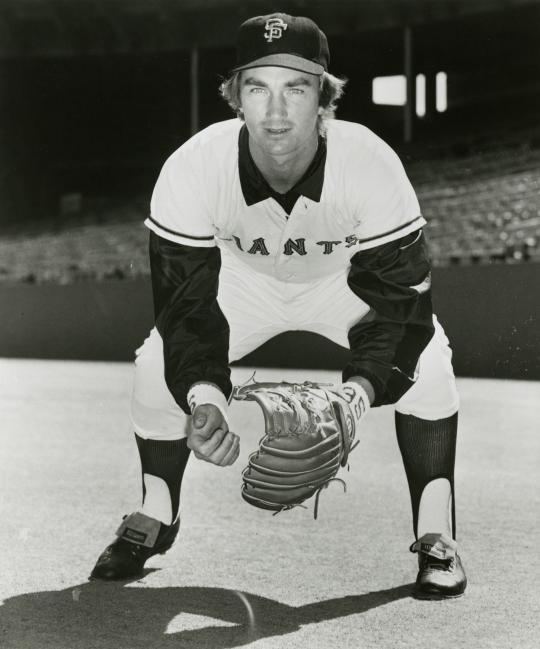

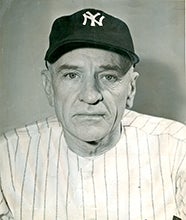

Teaming with young shortstop Chris Speier (pictured above), Tito Fuentes helped the San Francisco Giants finish in third place in the Western Division in 1973. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

With his outgoing nature, it only seemed natural for Fuentes to pursue a career in broadcasting. At first, he became a Spanish language announcer for the A’s before switching to the Giants in 1981 and remaining in that capacity through 1992. And then, after a stint with Fox Sports International, he returned to the Giants in 2005. He has remained with the Giants ever since.

The funky headbands are no longer needed, and the chin beard has long since disappeared. But the talkative and popular man nicknamed Parakeet, one with many stories to tell, has found a good home in the broadcasting booth.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame